Fort Sumter was the beginning not only of a bloody conflict, but it forged a generation of war correspondents that would culminate in live action reporting one-hundred and thirty years later.

These faltering beginnings by the Civil War correspondents would reach their highest form during the Desert Storm war.

During this action, Americans saw on prime time television the missiles fired and heard the roar of another attack bomber sortie. Several times during the day, generals and commanders briefed the press and the world on the day’s events. Battle maps, troops and equipment were flashed and paraded across television screens.

Later, in Somalia, the press greeted camouflaged Special Forces coming ashore in a pre-dawn invasion.

Modern warfare and military exercises have become media events.

In contrast, with no press briefings during the Civil War, there were differences between Union and Confederate newspapers, editors, and journalists in their reporting of this historic event. The people affected by the war often knew little of what was happening when it was happening.

The Civil War press was not always objective in reporting news of the war. Often opinions expressed by both Union and Confederate editors were unpopular in their home regions.

Also, the quality of Civil War correspondence left much to be desired. Henry Villard said the war produced no great reporter and that war correspondence had deteriorated steadily from 1862.

Edwin Godkin, founder of the postwar Nation said his colleagues’ reports were “. . .a series of wild ravings about the roaring of the guns and the whizzing of the shells and the superhuman valour of the men, interspersed with fulsome puffs of some captain or colonel with whom they happened to pass in the night.”

Anthony Trollope concluded that American newspapers were unreadable. And as if to pen the final rites on Civil War journalism, Charles Nordhoff, managing editor of the N. Y. Evening Post, wrote a scathing indictment of the war time press in Harper’s Monthly in June 1863, after visiting Port Royal:

How little—how very little, we who stay at home know of the war or of our soldiers!. . . The men who have written its history in the daily journals have been almost without exception. . . reporters in the lowest and poorest sense of the term …”

As the war progressed, Southern newspapers suffered for lack of paper, ink, and even manpower. As early as May 23, 1861, many Southern papers were printing half-sheets. By the spring of 1863, every Richmond daily was printed this way. In addition, the South lacked a truly metropolitan press.

Although Richmond had 37,910 people in 1860 with its population increasing during the war the Dispatch, its largest paper, never exceeded 18,000 circulation.

New Orleans, with more than 100,000 residents, fell to Union forces in 1862. But on January 18, the Daily Picayune pined that all of its reporters had enlisted.

The Press Association of the Confederate States was formed by resourceful Southern editors to pool their war news. The news they reported came from official reports, staff officers providing occasional contributions, and from Northern papers. In a sense, the latter provided war news for both sides.

For Southerners and Northerners, newspapers of 1860 were the most popular form of literature. Most people read nothing else. As talk of secession and imminent war increased, newspapers became even more important in both the South and the North.

The way news was selected and interpreted had great influence in developing Southern viewpoints on many subjects. This was particularly true on the eve of the Civil War. Southern newspapers were one of the most important sources for a clear understanding of why the South seceded.

However, Southern editors carefully selected news that reflected their personal viewpoints. Most Southern papers clipped much of their news from other journals they received in exchange for their own. Thus much of the “news” was material that had been lifted bodily—often without acknowledgment—from other journals.

The Northern press was better equipped. This proved true during its coverage of the war. During the war’s first two years, leading New York papers paid $60,000 to $100,000 annually to transmit dispatches by telegraph. From 1861 to 1865, the N. Y. Herald spent more than $500,000 to cover the war from the front.

Northern press coverage of the eastern campaigns was considered the best. Yet when military defeats resulted, official censorship halted truthful accounts. One historian said much of the Northern press inaccuracy was accidental, or at any rate unintentional. According to the journalists’ axiom: You’re only as good as your news sources. Often these proved grossly unreliable.

Reporters writing about the Civil War, or the events leading up to the war, were not always popular even in their own territory. Destruction of newspaper offices as well as threats to life and liberty of editors and reporters were common occurrences, particularly in the North.

In 1861, several New York newspapers were charged with pro-Confederate leanings. Among those brought to court were the Brooklyn Eagle, the N. Y. Journal of Commerce, and the N. Y. Daily News. In September 1861, the Louisville Courier was denied the use of postal service. The newspaper’s alleged hostility to the Union cause resulted in the arrest of several employees by Federal officials when the Courier’s office was seized.

Violence was common against Northern newspapers that shared Southern sympathies. When Ohio Congressman Clement Vallandigham was arrested by Union soldiers, his friends rushed to the street with torches attacking and damaging the office of the Dayton Daily Journal.

In Haverhill, Massachusetts, the editor of a pro-Confederate weekly newspaper was tarred and feathered and ridden through town on a rail. The Philadelphia Inquirer reported he was forced to swear he would never again publish articles “against the North and in favor of secession.”

Anti-draft uprisings in New York and other northeastern cities and towns often resulted in damage to local pro-draft newspapers. Horace Greeley’s pro-draft TV. Y. Tribune was damaged before rioters were driven off by a massive police assault.

Although not always pro-Confederate, some Northern newspapers took issue with Abraham Lincoln’s failure to attack the Confederate Army in Northern Virginia during the early stages of the war. These newspapers fussed at the President over the presence of “a rebel” army at the doorstep of the capital.

Southern newspapers, although declining in number as the war progressed, were equally critical of their government and leaders. Many Southern papers became bitter critics of President Jefferson Davis’s government even though most endorsed secession.

Led by the Richmond Examiner, the city’s five dailies persistently attacked the President’s cabinet appointments. Newspapers in Lynchburg, Raleigh, Augusta, and Charles Town heaped abuse upon Davis. One even blamed him for Confederate soldiers marching in snow without shoes.

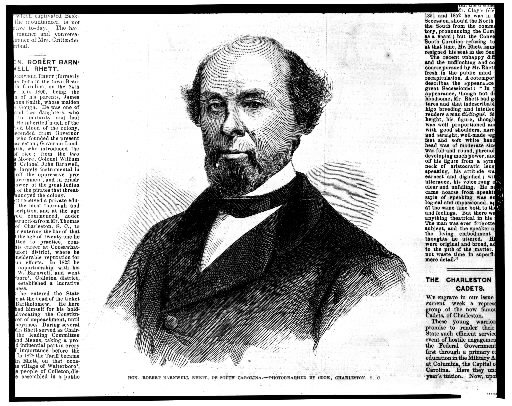

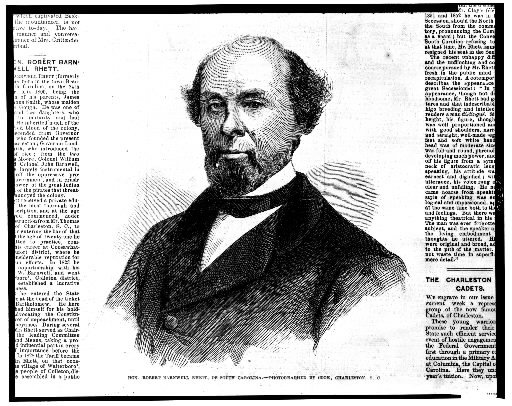

Robert Barnwell Rhett, Jr., editor of the Charleston Mercury once referred to Jefferson Davis as “this little head of a great country.”

Through it all, Davis and the Confederate government strongly supported the principle of a free press. They continued to tolerate newspaper criticism with unflinching patience.

Although there were censorship laws and Confederate military decrees against publishing news of troop concentrations and movements, the Southern press paid little attention to it.

Southern editors believed it their right—even their duty—to print campaign plans, detailed information about troops, schedules of blockade runners, and the size and location of war industries.

The precision of their reports caused Southern diarist Mary Chesnut to write that the North required no spies for “our own newspapers tell every word there is to be told by friend or foe.”

Some historical writers have said the lack of censorship of the Southern press “undoubtedly contributed to the deterioration of civilian morale and the loss of a will to fight.”

Reporting detailed war news and troop movements was not confined to the South. Confederate generals read Northern papers to learn of their opponent’s strength and strategy.

General Robert E. Lee sent President Jefferson Davis the April 26, 1864 edition of the Philadelphia Inquirer. He included this note:

“I send you the Philadelphia Inquirer of the 26th, from which you will learn that all [General Ambrose] Burnside’s available forces are being advanced to the front.”

Union generals were aware of the many news leaks, and they fumed over them as heatedly as their Confederate counterparts. Many saw them as treason and urged treatment of the culprits accordingly. Although some news aided the Confederate generals, much was too grossly inaccurate to be a threat to Union forces. Less scrupulous correspondents fabricated eyewitness accounts of battles they never saw! Some maps were so imaginary as to be mocked as “pictures of a drunkard’s stomach.”

Charles Page of the N. Y. Tribune wrote: “With watermelons and whiskey ready when officers come from the fight, I get news without asking questions.”

Perhaps one of the most notable Civil War personalities who found himself at odds with the press was General William T. Sherman.

His battles with the press began as a result of a meeting he had with visiting Secretary of War Simon Cameron. At the meeting, Sherman told the Secretary he needed 60,000 additional troops to drive Confederates from Kentucky, and at least 200,000 to fight his way to the Gulf of Mexico.

The Secretary, who began his political career by becoming owner of a Harrisburg, Pennsylvania newspaper was accompanied to the meeting by a N.Y. Tribune reporter. Sherman was not introduced to the reporter and therefore did not know his profession.

Subsequent newspaper accounts of the meeting misinterpreted Sherman’s request for troops. They said the general was “insane,” “stark mad,” and displayed “strange conduct.”

As a result, Sherman was removed from command and almost had his military career ruined.

Although bitter about the incident, Sherman’s real war with the press began after his unsuccessful attack at Chickasaw Bluffs outside Vicksburg in 1862. In this attack, Sherman’s failure to succeed was the result of General U. S. Grant not supplying him with expected support.

Nonetheless, Sherman was attacked in the N.Y. Herald by correspondent Thomas W. Knox. In his six-column story of January 18, 1863, Knox said,

“General Sherman was so exceedingly erratic that the discussion of twelve months ago with respect to his sanity was revived with much earnestness. . . Insanity and inefficiency have brought their result. Let us have them no more.”

Knox was arrested and brought to Sherman who read the story aloud and demanded to know the sources for his assertions of military incompetence.

In typical sarcasm, Knox said, “you are regarded as the enemy of our set, and we must in self-defense write you down.”

Sherman had Knox held for court martial under War Department General Orders No. 67, which included that any news report concerning the Army be approved in advance by the commanding general on the scene.

Ultimately, Knox was acquitted of the most serious charges, but was expelled from the area.

Later when Sherman learned of three reporters blown out of the water while attempting to run the Vicksburg batteries, he supposedly said: “Good! Now we’ll have news from hell before breakfast.”

(Ironically, Sherman’s post-war leniency toward the South was criticized by his own people. He told delegates at a convention in Little Rock, Arkansas in December 1865, to turn their energies away from protesting exclusion of ex-Confederates from politics and to turn toward developing their state’s resources.)

Citizens, both Southern and Northern, developed opinions and attitudes about the war from the newspapers they read. From the journalists’ reports, people in Virginia as well as New York determined if their generals were capable.

In his book The Destructive War, Charles Royster said:

“. . . Through praising or damning generals and by forming a notion of an ideal general, civilians took a hand in the war, proclaiming themselves fit to judge how it should be directed. Newspapers expressed, shaped, and sometimes manufactured impressions of popular opinion; in turn, civilians depended on newspapers for most of their immediate vicarious participation in the war. Despite intertwined rivalries among generals and among newspapermen, the armies’ commanders and the press appeared to offer people their best hope of guiding the war.”

Reporting of casualties was a common practice with both Northern and Southern papers. The Union War Department eventually stopped the practice. Previously, Northern papers published long lists of casualties by name specifically telling what part of the body received the wound. If not wounded, the simple notation “killed” was listed. Southern newspapers continued reporting casualty lists throughout the war.

Some critics, particularly the armies, believed civilian interest in casualty lists and battle narratives exceeded their concern for loved ones or their nation. Many thought it was more a morbid interest in the s war.

The interest in war news was probably best expressed by Oliver Wendell Holmes who read the reports intently. Writing in the Atlantic, Holmes said: “We must have something to eat and the papers to read. Everything else we can do without . . . Only bread and newspapers we must have.”

The Civil War also introduced picture journalism. Soon to follow would be the beginnings of photojournalism. Eyewitness sketches by Alfred and William Waud, Henri Lovie, Winslow Homer, and Edwin Forbes were transformed into engravings in Harper’s and Leslie’s. Through this medium, the specter of war and its suffering would be brought to thousands who would never see a battlefield.

Mathew Brady is perhaps the most well known Civil War photographer. Many others were in the field recording the awfulness of the conflict. Action photographs of the Civil War are static representations of events before or after action.

Actual photographs taken were seldom seen. A process had to be developed for mass publication. Civilians saw the war through the efforts of woodcuts. Thus illustrators brought the war home most.

But like their reporter kinsmen, some of the illustrators were equally accused of inaccuracies. General George McClellan said pictures of Union fieldworks were more likely to confound the Confederates than to aid them.

In Harper’s Weekly, an engraving showed a cavalry officer running his saber through the back of a victim so that a foot of it protruded from his chest.

Frank Leslie’s, Harper’s and the N. Y. Illustrated News accused each other of drawing battle scenes in their offices.

One Cincinnati Gazette reporter said, “Those who draw their conceptions of the appearance of the rebel soldiery from Harper’s Weekly would hardly recognize one on sight.”

Alexander Gardner joined Mathew Brady in photographing the war. Civil War photographers worked with the permission and cooperation of the army. Gardner had an honorary appointment on the staff and was actually paid by the Union Army.

Although Brady covered the war more extensively, he used a group of photographers (Gardner among them) who took pictures of various aspects and battles of the war. Brady rarely went into the field, and when he did, he was run off by army officers.

Although there were some Southern photographers in the field, they were few because supplies and paper were short.

Noted photographers, illustrators, and artists working in the field during the Civil War included George Armstead who took pictures of Confederates. When the Union forces arrived in Corinth, Mississippi, he took their pictures. Samuel Cooley traveled with General Phillip Sheridan in the Department of the South and saw the destruction of Richmond. A. D. Little was a Southern photographer who worked for the Confederate Secret Service. George S. Cook was a Charleston photographer who took “action” photographs from Fort Sumter while it was under fire by three Union ironclads. Alfred Waud, the most prolific illustrator, covered the war from First Manassas to Appomattox. Theodore Davis was a Harper’s Weekly illustrator who heavily documented his work. He was perhaps the most traveled war correspondent, covering more of the war than all the others. He was with Grant at Vicksburg. Edwin Forbes was an artillery specialist attached to the Army of the Potomac for most of the war.

As the war continued, Southern newspapers suffered greatly. Not only were paper and ink in short supply, but by 1864 the Southern telegraph system was almost non existent. As Sherman continued his march to the sea, the limited telegraph poles, wire, and insulators were destroyed.

In addition to the newspapers’ plight, the morale of the Southern people was waning as the war continued and their country was being destroyed. By the first weeks of January 1865, the Southern press was unable to conceal the despair of the people.

The fall of Vicksburg on July 4, 1863, was symbolic of what was happening throughout the South. And the final edition of The Daily Citizen gave credence to the plight of other Southern newspapers.

The Daily Citizen was edited and published by J. M. Swords. Like several other Southern newspapers, its stock of paper was exhausted and the editor resorted to the use of wallpaper.

On this substitute, editor Swords printed issues of June 16, 18, 20, 27, 30, and July 2, 1863. Each was a single sheet, four columns wide, printed on the back of wallpaper.

When Vicksburg surrendered on July 4, Swords left and Union forces found the type of The Daily Citizen still standing. They replaced two-thirds of the last column with other matter already in type and added this note:

JULY 4, 1863

Two days bring about great changes. The banner of the Union floats over Vicksburg. Gen. Grant has “caught the rabbit;” he has dined in Vicksburg, and he did bring his dinner with him. The “Citizen” lives to see it. For the last time it appears on “Wall-paper. ” No more will it eulogize the luxury of mule-meat- and fricasseed kitten-urge Southern warriors to such diet never-more. This is the last wall-paper edition, and is, excepting this note, from the types as we found them. It will be valuable hereafter as a curiosity.

Evidently after a few copies (how many is unknown) had been run off, it was noticed that the masthead title was misspelled as “CTIZEN.” The error was corrected, although the other typographical errors were allowed to stand, and the rest of the edition printed.

Though no Southern newsmen were at the Wilmer McLean home Wednesday, April 12, 1865, Jerome B. Stillson of the N. Y. World provided a detailed account of the historical event which greeted readers on the front page of the April 14, 1865 edition. In it, he offered honor to both Lee and Grant as men who know the true price of war:

“After a few minutes of private desultory conversation, General Lee took his departure, General Grant attending him to the door, and taking his hand at the threshold. The entire interview was conducted, on the part of General Lee, with the manly but conscious bearing of a soldier fairly beaten, but not cowed. . .”

This essay was originally printed in the 1st Quarter 1994 issue of Southern Partisan magazine.