Following the senseless racial murders at a Charleston, South Carolina, church in 2015, Hollywood’s moonshining Duke boys from fictitious Hazzard County, and more particularly their 1969 Dodge Charger “General Lee,” replete with a Confederate Battle Flag painted on its roof, were placed on the growing list of Southern images to be erased from public view. Not only were scheduled reruns of the popular television show of the 1980s immediately cancelled, but Warner Brothers also recalled all models of the “General Lee” from the studio’s theme shops. To carry this inanity even further, after the Charleston incident Florida golfer Bubba Watson, who had purchased and restored the wreck of the original “General Lee,” joined the anti-Confederate parade and announced that he would repaint the car’s roof with an American Flag. However, the Dukes who are the subject of this piece are not the actors from the imaginary Hazzard County in Georgia. but the very real Duke family from Orange County in North Carolina, and the hazard in this case is the product for which they would become world famous, cigarettes.

The Duke’s involvement in the tobacco industry had its genesis following the War Between the States on a burned out three hundred acre farm near Durham, North Carolina. Its owner, George Washington Duke, had been a reluctant participant in the War and while he owned one female slave, Duke had been opposed to both slavery and secession, and refused to volunteer for Confederate service. While at forty-two he was too old for the initial military draft in 1862, after the age limit was raised the following year he was drafted into the Confederate Navy and served in Charleston and Richmond. In 1864, Duke was transferred to the Army and assigned to the Army of Northern Virginia at Petersburg as an orderly sergeant. He was captured just prior to General Lee’s surrender at Appomattox and after the fall of Richmond, was held there at Libby Prison, the former place of confinement for captured Union officers that had once, oddly enough, been a tobacco warehouse. Following the final collapse of the Confederacy, Duke was released and sent by ship to New Bern, North Carolina. As the only funds he had was a fifty-cent coin he had obtained from a Union soldier in exchange for a five-dollar Confederate note, Duke had to walk the hundred thirty-seven miles back to his farm. Upon arriving home, he found all that had been left by General Sherman’s marauding “bummers” were two blind mules and a log shed in which s small quantity of leaf tobacco had been hidden. From these humble beginnings there was to emerge in only two decades, a business that was once the largest tobacco empire in the world, the American Tobacco Company.

The Duke family can be traced back to someone named Walter Toke, or Tooke, in Fifteenth Century England, with the first of the family to come to America being Henry Duke, who was born on July 8, 1642, at Aylesford in Kent, England. Sometime prior to 1670, Duke decided to leave England and traveled first to the island of Bermuda, but was soon to set sail again for James City County in the Virginia Colony where the original settlement of Jamestown was located and was one of the four “incorporations” into which the Colony had been divided in 1619. He was later joined by his parents, Thomas and Mary Duke, who established a farm in the former Nansemond County that is now the city of Suffolk in Virginia’s Isle of Wight County and lived there until Thomas’ death in 1682 and his wife’s a year later. Prior to coming to America, the elder Duke had been a cloth merchant, or draper, in Aylesford. After his arrival in Virginia, their son Henry was selected as a county justice, as well as being commissioned a colonel in the militia. In 1690, he was asked by Colonial Governor Francis Nicholson to solicit funds for a free school in Williamsburg, later to become the College of William and Mary. Then, from 1692 to 1699, Duke served as a member of the House of Burgesses, after which he was appointed sheriff of James City County. In 1702, Queen Anne appointed Duke to the Colony’s Royal Council, and later as a judge of the Admiralty Court where one of the cases to came before him was that of a woman named Grace Sherwood who had been charged with witchcraft. Shortly before his death on March 9, 1714, Duke had also served as auditor general for the Colony.

George Washington Duke’s great grandfather William moved from Virginia to Brunswick, North Carolina, prior to the Revolutionary War, and his son John later relocated to Orange County near Durham where he established a small farm on the Little River. John Duke married Lydia Lewis in Brunswick and they had five children, the fourth being Taylor Duke who was born in 1770. Taylor married Dicey Jones, and they had ten children, the eighth was George Washington who was born on December 18, 1820. Coming from a poor family, the boy received very little education and had to work as a tenant farmer at an early age. It was not until he married Mary Caroline Clinton in 1842 and received seventy-two acres of land from her father that he could establish his own farm. During the next two decades, Duke managed to add more land to his farm and by the start of the War Between the States he had three hundred acres, some of which was devoted to growing tobacco. Since his one female slave, Caroline, did only household chores and he could not afford to purchase other slaves for farm work, as well as personally disliking the practice of slavery, Duke hired slaves from other farms. When he returned to his farm after the War, since the property lay in ruins he decided to forego farming and try to market the small amount of tobacco that the Union troops had overlooked. To raise capital, Duke sold his land and then rented back a small portion on which he and two of his sons, Benjamin and Buchanan, better known as “Buck,” processed the leaves and packaged them in small muslin bags for use as pipe tobacco with the brand name “Pro Bono Publico” . . . for the public good. The product was taken to Raleigh in a cart pulled by the two blind mules that had been spared by the Yankees and the product sold well. Within a year, Duke had formed a company, W. Duke and Sons, produced fifteen thousand pounds of tobacco and built a new frame processing plant on their land. By 1869, the company had moved into a two-story building in Durham and added additional brands of smoking and chewing tobacco.

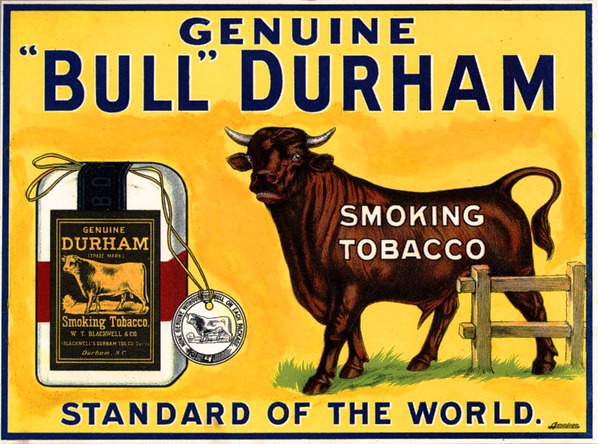

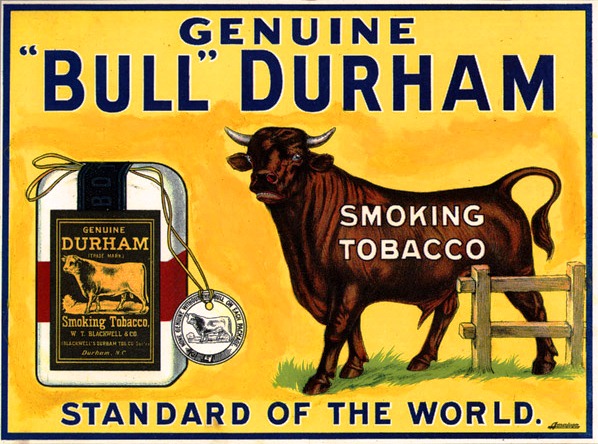

The Dukes, however, faced strong competition from a rival firm in Durham, the W. T. Blackwell Company that sold the extremely popular “Bull Durham” brand. The competition was so stiff that by 1881 “Buck” Duke had decided to add a completely new product to their line, cigarettes. The new product had names such as Cameo, Cross Cut, Cyclone and Duke’s Best, with a box of ten cigarettes selling for three cents. Until that time, daily production had been limited to a few hundred cigarettes due the need for hand rolling, even with expert rollers young Duke had brought in from New York. That same year, a Virginian named James Bonsack introduced his mechanical cigarette rolling machine and with two such devices, the Dukes began turning out over two hundred cigarettes a minute. By 1889, the four leading tobacco companies were producing over two billion cigarettes annually, with W. Duke and Sons accounting for almost forty per cent of that number. The following year, “Buck” Duke formed the four firms into a conglomerate capitalized at twenty-five million dollars and called it the American Tobacco Company, with Duke as its president. Anti-trust regulations finally caught up with the Duke empire in the early part of the Twentieth Century, and its virtual monopoly was broken up into a number of independent companies. By the latter part of the century, there were just six major tobacco firms, with Philip Morris and R. J. Reynolds controlling over seventy per cent of the market, and American Tobacco having less than a tenth of that.

As to tobacco itself, the plant, which is related to tomatoes, peppers, potatoes, eggplant, and the highly toxic belladonna, or deadly nightshade, first appeared in South and Central America about eight thousand years ago. Shortly before the beginning of the First Century, Amerindians were already using tobacco for medicinal and religious purposes, with the tribes in the Caribbean smoking it through the nose via tubes made of dried, rolled up leaves which they called tavaco. Columbus was the first to witness this practice on Cuba in 1492 and with the name corrupted into tobacco, smoking was introduced to Europe. By 1531, the Spanish settlers on Santo Domingo were cultivating the leaf and in 1612 John Rolf of Virginia, who had married the native princess Pocahontas, began the commercial growing of tobacco in the Colony. While it may be thought that the anti-smoking movement is of fairly recent provenance, King James I of Great Britain detested the habit and after he failed to stop its growth in the American Colonies or its export to England, he imposed a four thousand per cent import tariff on tobacco. In spite of this, tobacco exports to Europe continued to rise rapidly and by 1630, almost a thousand tons were being shipped annually from the Virginia Colony. Tobacco remained the South’s leading export for more than a century until it was finally overtaken and greatly surpassed by cotton. On the other side of the world, after tobacco was introduced into Japan by the Portuguese in the Sixteenth Century, the Tokugawa Shoganate also considered the habit so vile that the importation of tobacco was banned entirely. Like prohibition in America, however, such a ban proved unenforceable in Japan, with tobacco becoming a major crop in the country, as well as a government monopoly in 1898 and smoking a nationwide habit.

Even in the United States, by the late 1800s cigarettes were already being thought of as hazardous to one’s health and were referred to as coffin nails. In 1899, the Anti-Cigarette League of America was started by Lucy Page Gaston of Illinois whose family had a long history of abolitionist and temperance activities. The League sought to ban not only cigarettes, but all smoking in public places, and by 1917 eight States had made cigarette smoking illegal, with several other States considering such legislation. Many well-known Americans, such as Thomas Edison and Henry Ford, led campaigns against cigarettes, with Edison refusing to hire anyone who smoked them and Ford publishing four volumes of statements entitled “The Case Against the Little White Slayer.” America’s entry into World War One called a halt the drive, however, and millions of cigarettes were donated to the military by the tobacco companies, as well as their lobbying having them included as a standard item in military rations. After the War, a number of other factors arose, such as smoking in motion pictures, the hedonism of the Roaring Twenties and saturation radio, and later television, advertising, all of which were designed to make smoking cigarettes appear both sophisticated and glamorous, and cigarette smoking reached new heights. From 1920 to 1960, the annual per capita use of cigarettes rose from less than sixty to over four thousand. Then came various studies linking smoking directly to cancer and lung disease, particularly the Surgeon General’s report in 1964, which ultimately led to a number of successful private legal actions against the major tobacco companies and the banning of tobacco advertising on radio, television and in print media. Along with this, much higher taxes imposed by all levels of government and ever-rising domestic production costs all led to the per capita use of cigarettes in America to be cut in half by the start of the present century.

As a footnote, when considering the sense of smoking, or the lack of it, one might well remember comedian Bob Newhart’s anachronistic 1962 telephone conversation between Sir Walter Raleigh in Virginia and someone at the East India Trading Company in London. In that imaginary call, Raleigh, who is referred to as “Nutty Walt,” is asked what is the latest item being sent to them from America. He tells them he is sending eighty tons of tobacco and when the name seems unfamiliar, he explains that it is a dry leaf that is shredded, rolled in paper and ignited, with the smoke being inhaled. All of which is met with gales of laughter in London. If you really think about it though, in addition to the now well-known hazards posed to one’s health and well being by smoking, such an inane telephone conversation might also tend to make the habit itself seem just as ridiculous.