Constitutional Violation: Amendment One: Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

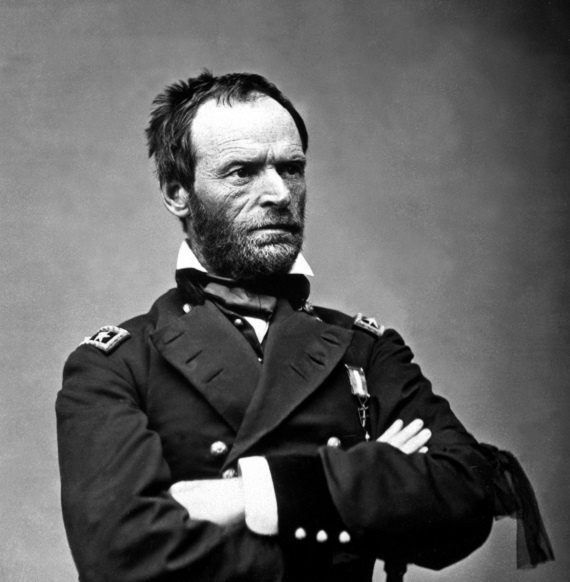

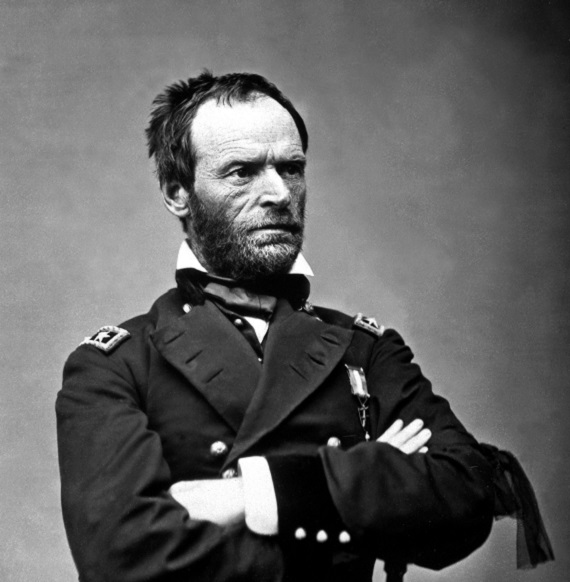

“Freedom of speech and freedom of the press, precious relics of former history, must not be construed too largely.” General William T. Sherman

In the original American model, freedom of speech, press, and religion were literally God-given cornerstones of liberty. Lincoln sought to squelch or eliminate freedom of speech and freedom of the press for any Northern (and Border State) citizen who criticized the war through speech or print or objected to the draft. Numerous States felt the full force of this policy.

Kentucky—Lincoln held a general paranoia about losing the State, exclaiming, “I hope to have God on my side, but I must have Kentucky.” Wishing to remain neutral, the Kentucky legislature passed a resolution claiming their neutrality and disallowing troops from either side to belligerently pass through or occupy her soil. The pro-Union political element in Kentucky led her citizens into thinking they would get their wish. “The Federal Government had disregarded the neutrality of Kentucky, and Mr. Lincoln had hooted it…”

Legislators were elected in August, and as the results were known “it soon became evident that the Federals intended to occupy Kentucky, and to use her roads and mountains for marching invading columns upon the Confederate States.” In September 1861, Confederate General Leonidas Polk moved into Columbus, Kentucky, despite orders from Jefferson Davis to stay out. Davis wanted to respect Kentucky’s desire to remain neutral and refrain from putting political or military pressure on the State to join the Confederacy. Polk’s miscalculation led to Kentucky’s request for Union assistance. This allowed Grant an opportunity to take Paducah, and establish a Union presence in the State. In response to Kentucky Governor Beriah Magoffin’s request for all troops to leave his State, Polk agreed to withdraw if Federal forces withdrew simultaneously.

There was no intention of forcing the State to side with the Confederacy; strategically, a neutral Kentucky was geographically positioned to serve as a buffer zone advantageous to the South. Despite Union promises to the contrary, “it was well understood that the people of that State had been deceived into a mistaken security, were unarmed, and in danger of being subjugated by the Federal forces,….” The general sentiment was that most Kentuckians identified themselves culturally as Southern, and, given the right to choose, most would likely side with the Confederacy. Magoffin had also refused Lincoln’s request to furnish troops to coerce the seceded States. Lincoln was determined to do whatever was necessary to keep Kentucky from joining the Confederacy.

There was divided sentiment in Kentucky regarding the slavery issue and Lincoln sent mixed signals himself. Norman Hapgood, Illinois-born writer, editor, and journalist quoted Lincoln from a September 22, 1862, confidential letter sent to Illinois Republican Senator Orville H. Browning referencing one reason he denied the enactment of Fremont’s proclamation. “The Kentucky Legislature would not budge—would be turned against us. I think to lose Kentucky is nearly the same as to lose the whole game. Kentucky gone, we cannot hold Missouri, nor, I think, Maryland.” The letter referenced Lincoln’s veto of Union Major General John Fremont’s August 30, 1861, order to free the slaves in Missouri. Also, on May 9, 1862, Union Major General David Hunter issued an emancipation order, declaring, “‘slavery and martial law in a free country are altogether incompatible’ and all former slaves in his command, the Department of the South, ‘are therefore declared forever free.’” As with Fremont’s declaration, Lincoln quickly vetoed it.

George D. Prentice, a pro-Union, anti-abolitionist, edited the pro-Republican Louisville Journal. While Prentice had no reason to fear suppression or closure, the Louisville Courier did. The Courier’s editor, Walter N. Haldeman, was a strong supporter of the Confederacy. When Kentucky’s neutrality ended, the Courier was suppressed and later published in Bowling Green as long as a Confederate presence remained. “Less outspoken than Haldeman, John H. Harney, editor of the Louisville Democrat, became the voice of the Peace Democrats; he grew increasingly critical of Lincoln and his policies…; the Kentucky Yeoman, which had supported secession, modified its views sufficiently that it avoided suppression. A number of small newspapers were victims of wartime shortages and high prices or were suppressed by the army.”

With abundant pro-South and anti-war sentiment in the State, Union forces in Kentucky were leery of incidents such as John Hunt Morgan’s raids early in the war. Kentucky-born Brigadier General J.T. Boyle referenced this fear in a July 19, 1862, letter to Secretary Stanton. Boyle feared Morgan’s meager force of perhaps 3500 men would overrun the State. In another correspondence from Boyle to Stanton, he stated that Morgan’s forces had a maximum of 1200 men and “There are bands of guerillas in Henderson, Davis, and Webster counties.” Alluding to Anti-war/Pro-Southern sentiment within Indiana, Illinois, and other Northern States, Ohio Governor John Brough wrote Secretary Stanton on June 9, 1864, expressing his belief that Kentucky would have to be treated like Maryland to keep them in line. On July 5, 1864, referencing his September 15, 1863, proclamation, Lincoln declared martial law and suspended the writ of habeas corpus in Kentucky.

A footnote of history involving Kentucky was General Order No. 11, issued by U.S. Grant on December 17, 1862. This order called for all Jews to be expelled from his district, i.e., Kentucky, Tennessee, and Mississippi. This blatantly bigoted order, based on the allegation that Jews spearheaded an unprincipled black market trade was short-lived and has been generally ignored by historians. Years later, as a candidate for president, Grant said he did not read the order before he signed it and placed the blame on a subordinate.

Indiana—Indiana was subject to shutdowns of the press. Having few large newspapers in the State, the closures were of smaller, more local Democratic papers. The high point of this activity was in the spring of 1863. Union Brigadier General Milo Hascall, a native New Yorker, had lived in Goshen, Indiana since 1847. On April 25, 1863, Hascall issued Order No. 9, as his version of Burnside’s Order No. 38. Both orders were spurred by the intense anti-war sentiment in the North. Hascall claimed, “The country will have to be saved or lost during the time this administration remains in power, and therefore he who is factiously and actively opposed to the war policy of the Administration, is as much opposed to his Government.” Hascall echoed the familiar mantra often associated with centralizers that you are either with us or against us, leaving no room for middle ground. “The first editor arrested was Daniel E. Van Valkenburgh of the Plymouth Weekly Democrat.” VanValkenburgh had ridiculed Order No. 9 as well as its author and was arrested on May 4, 1863.

There were other arrests of Democratic newspaper editors. “Rufus Magee, editor of the Pulaski Democrat in Winamac, was arrested and his newspaper suspended for two weeks…The Columbia City News was shut down and its editor, Englebert Zimmerman, was ordered to Indianapolis to answer for his offense.” Given the option of retracting its condemnation of Order No. 9 or closing its publication, W.H. and Ariel Draper, editors of the Democratic South Bend Forum, decided to shut it down. Other Democratic publications that were threatened by Hascall “included the Starke County Press, the Bluffton Banner, the Blackford Democrat, the Warsaw Union, and the Franklin Weekly Democratic Herald.”

General sentiment in Indiana was unfavorable toward the abolitionists, realizing that radical elements existed within the movement. Apparently, many Indianans wanted to distance themselves from the slavery issue altogether. A new constitution had been submitted to the people of Indiana in 1851. This constitution forbade Blacks from coming to the State and it levied punishment on anyone who employed them. A popular majority of almost 90,000 ratified it. Indiana Governor Oliver P. Morton, a Radical Republican, and a steady opponent of the abolitionists, supported this new State constitution. Harrison H. Dodd provided another perspective. Dodd, born in New York, later moved to Ohio and finally Indiana, where he served as the Grand Commander of the Sons of Liberty. He commented that “‘the real cause of the war was the breach of faith by the North in not adhering to the original compact of the States…that ‘in twenty-three States we had governments assisting the tyrants at Washington to carry on a military despotism.’”

From the Lincoln Administration’s standpoint, Indiana had too many army desertions and too many of its citizens favoring peace with the South. There was armed resistance in Rush County, and the Union Army “sent one hundred infantry by special train to arrest deserters and ringleaders. Southern Indiana is ripe for revolution.” Meetings were held on the local and county level in many parts of the State; the results of some of these meetings “…declared the war cruel and unnecessary, denounced President Lincoln as a tyrant and usurper…”

Ohio—Clement Vallandigham was not the only Ohioan who disagreed with the war. Lincoln’s supporters flexed their military and political muscle, as they felt necessary to silence resistance. Burnside’s district consisted of Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois and within his region the New York Herald was excluded and the Chicago Times suppressed. This was an area absent of war, but anti-war and anti-draft sentiment was often openly expressed. Ohio’s Governor Brough wrote to Stanton on August 9, 1864, lamenting the slow recruitment of new soldiers. He predicted the necessity of a heavy draft and encouraged the use of strong force against those who resisted. Brough, a strong Lincoln supporter, had already meddled in the affairs of Kentucky.

Three Muskingham River Valley Democratic-leaning newspapers were targeted—“the McConnelsville Enquirer, Zanesville Citizens’ Press, and Marietta Republican…operatives in the Republican Party circulated a document that states the Enquirer had discouraged enlistments…and In March 1863, a mob ransacked the office of the Marietta Republican.” The Democrats of Washington County met and proclaimed that a free press and a free conscience should be allowed in wartime just as in times of peace. Samuel Chapman, editor of the Citizens’ Press, was threatened by Burnside, and then arrested for his own protection against a mob, so he shut down the paper. Continuing the aggression against Democratic, anti-war papers, “in March 1863, Company M of the Second Ohio Volunteer Cavalry attacked the Columbus Crises, a relatively new Democratic newspaper owned by Samuel Medary.” Another publication that faced suppression was the Ohio Democrat, based out of Starke County.

Illinois—The citizens of Illinois had a strong aversion to emancipation and enacted a law similar to Indiana, disallowing Blacks from living in their State. In his Life of Oliver P. Morton, William Dudley Foulke shows that, in January 1863, the Illinois General assembly offered several resolutions; some that passed were against emancipation and conscription. Like Indiana, there was severe resistance to the war within the general population. Illinois Governor Yates wrote to Stanton expressing the fear his State would face strong resistance to the draft.

Several newspapers were temporarily suppressed. One was the Jonesborogh Gazette (now Jonesboro) in Southern Illinois. The more high-profile Chicago Times perhaps initiated a rebuke from the Lincoln Administration by wondering in print how a Christian nation could engage in the slaughter of thousands of its own people without a valid motive. “To assume a different ground, would be to confess ourselves barbarians or demons. We then repeat the question as to what adequate motive we have for inaugurating a civil war?”

Burnside was behind the suppression of the Chicago Times. Wilbur F. Storey, an accomplished editor, took over the Times in June 1861. Though he was not initially anti-war, after the Emancipation Proclamation was issued, Storey denounced the folly of trying to change the goal of the war to emancipation. “On June 1, 1863, Burnside issued General Order No. 84, the suppression order for Storey’s newspaper.” Shortly thereafter a military officer shut down the Times and its presses. Questioning why the country should get involved in what many considered an unnecessary war drew a strong and sudden response from the Lincoln Administration.

Pennsylvania—There were pockets of resistance in the State of Pennsylvania. Reverend A.V.G. Allen, an Episcopal clergyman from Cambridge, Massachusetts, published several biographical works of fellow Massachusetts Episcopalian clergyman Phillips Brooks (who wrote the lyrics for ‘O Little Town of Bethlehem). In Life, &c., of Phillips Brooks, Allen states that in Philadelphia there was “avowed hostility towards the Government in its prosecution of the war. That such sentiments towards Lincoln and his Administration did exist in Philadelphia is evident, but it should also be said that the same apathy or hostility might be found in the Northern cities, in New York and in Boston.” The State of Pennsylvania contained strong support for the Democratic Party. In Philadelphia, Democrats were dominant, and despite the ongoing war, there remained anti-war and pro-South sentiment. Two Philadelphia papers—the Christian Observer and the Evening Journal—were suppressed for their criticism of the war. The Lincoln administration accused these papers of providing “aid and comfort” to the South. Other Pennsylvania newspapers that faced suppression included the Sentinel in Easton and the Jeffersonian in West Chester.

There were other forms of war resistance in Pennsylvania. For example, Captain Richard I. Dodge, acting Provost Marshall General, wrote to General Fry, Provost Marshall General, on August 10, 1864: “In several counties of the Western Division of Pennsylvania, particularly in Columbia and Cambria, I am credibly informed that there are large bands of deserters and delinquent drafted men banded together, armed and organized for resistance to the United States authorities.”

New York—In New York, Governor Horatio Seymour was one of the most prominent Northerners to come to the defense of the seceded States, acknowledging the legitimacy of their grievances and protesting Lincoln’s program of coercion. The anti-war and anti-draft sentiment of New York City was witnessed by Union General John Dix, who wrote to Secretary Stanton that State and city authorities could not be relied on to enforce the draft “and, while I impute no such designs to them, they are men in constant communication with them who, I am satisfied, desire nothing so much as a collision between the State and General Governments and an insurrection in the North in aid of the Southern rebellion.”

New York was America’s news center in the 1860s, and it was there that suppression of the print media began. Horace Greeley, originally a proponent of peace, eventually became a supporter of Lincoln and the war and his paper, the New York Tribune, reflected it. However, the Journal of Commerce and the New York Daily News were in opposition. Simply put, if the paper supported the Republicans and their war, it was safe from government interference whereas anti-war, pro-Democratic newspapers were open targets. “In May 1861 the Journal of Commerce published a list of more than a hundred Northern newspapers that had editorialized against going to war. The Lincoln Administration responded by ordering the Postmaster General to deny these papers mail delivery.” The New York Herald, the city’s largest newspaper, supported the legality of secession and opposed coercion, “But a mob compelled the publisher to change his tune, and editorials stopped expressing hostility to Lincoln’s war.” This same technique “was used by the Lincoln administration against the New York Daily News, The Daybrook, Brooklyn Eagle, Freeman’s Journal, and several other smaller New York newspapers.”

Iowa—In a seemingly unlikely place like Iowa, there was Pro-Southern sentiment. There was a legal case involving William H. Hill, an Iowan and Southern sympathizer, accused of discouraging enlistments and aiding the Confederate cause. U.S. Marshall Hoxie and Iowa Governor Kirkwood reported to Secretary Seward their belief that Hill was guilty, but both men felt he would be cleared because the jury is “in sympathy with the rebels.” In Hoxie’s December 1861 letter to Seward he stated there was little doubt as to Hill’s guilt but he would be found not guilty because “There is a large secession element in the jury selected to try him.” Like so many of the States in the Midwest, many Iowans had an aversion to war and recognized that the South had a valid constitutional position. In July 28, 1862, correspondence to Secretary Stanton, James F. Wilson reported from Fairfield, Iowa: “Men in this and surrounding counties are daily in the habit of denouncing the Government, the war, and all engaged in it, and are doing all they can to prevent enlistments;….’”

Iowa Catholics were leery of the strong antipathy toward their religion within the Republican Party, especially from former Know Nothings. The Dubuque Herald was anti-war and concerned about Lincoln’s armies being plunderers with a corresponding loss of civility. The Herald and the Iowa City Press were severe critics of the war. The Keokuk Constitution felt the wrath of their anti-Lincoln stance when a group of Union soldiers in a convalescent hospital took the law in their own hands. They literally destroyed the newspaper’s office. “The types were thrown into the street and the presses broken up and part of them thrown into the river.”

Wisconsin—Wisconsin Governor James T. Lewis sent a letter in August 1864, claiming there had been rampant fleeing from the draft in Wisconsin and Minnesota. According to Lewis, in Wisconsin, “Out of 17,000 drafted in this State during the last year, I am informed that but about 3,000 are in the service.” This was part of the sentiment throughout the Midwest that showed both strong resistance to war and belief in the voluntary nature of the U.S. Constitution.

When he described Lincoln as a butcher, bigot, fanatic, and a tyrant, Marcus “Brick” Pomeroy made quick enemies with the Lincoln Administration and supporters of the war. Considered a Copperhead during the war, “Pomeroy, editor of the La Crosse Democrat, had a turkey pushed into his face.” He was also threatened by a mob and questioned by a sheriff after his 1864 suggestion that Lincoln should be assassinated if reelected.

The Prairie Du Chien Courier was another anti-war, pro-Democratic Wisconsin newspaper. Though it was not subject to suppression, “William D. Merrell’s newspaper covered the murder of a Democratic politician by a mob of Union soldiers in New Lisbon, Wisconsin.”

Connecticut—Pro-Southern sympathy existed in the heart of the Northeast. In January 1862, Connecticut’s Deputy Collector, Fred H. Thompson, wrote to Union Secretary Seward about events in Bridgeport, claiming the city had pockets of strong sympathy for the Confederacy and that a Knights of the Golden Circle lodge was located there.

There was also suppression of Democratic newspapers in Connecticut; the Bridgeport Advertiser & Farmer ran afoul of both local Republicans and the Federal government due to its anti-Lincoln and anti-war stance. “The Farmer was indeed anti-Lincoln, calling him a ‘despot’ and accusing him of assuming more power than the Constitution allowed a President.” In Stepney, a scheduled Democratic Peace Meeting was interrupted by pro-Unionists, led by none other than P.T. Barnum. After threats of violence by both sides, the pro-Unionists marched south to Bridgeport and proceeded to attack the Farmer’s office where they destroyed the presses along with the books, paper, etc., and put the paper out of business. No arrests were made for the mob’s destruction of private property.

There were many other newspapers that felt the wrath of Lincoln and his supporters. A partial list of those censored or suppressed include the “Dayton Empire, Louisville Courier, Maryland News Sheet, Baltimore Gazette, Daily Baltimore Republican, Baltimore Bulletin, Philadelphia Evening Journal, New Orleans Advocate, New Orleans Courier, Baltimore Transcript, Thibodaux (Louisiana) Sentinel, Cambridge Democrat (Maryland), Wheeling Register, Memphis News, Baltimore Loyalist, and Louisville True Presbyterian.”

Other acts of oppression were directed at opposition opinions. “The editor of the Essex County Democrat in Haverhill, Massachusetts, was tarred and feathered by a mob of Unionists who destroyed the paper’s printing equipment.” Lincoln’s followers even harassed and suppressed non-American sources. A foreign newspaper operating in New York, “the French Courier des Etats Unis, was ordered to print the news of the day only, no commentaries, and its editor, M.E. Masseras, was ordered to resign.”

Additional States showed their disagreement with the war, draft efforts, and the disregard for the U.S. Constitution and the rule of law. In their book Abraham Lincoln, Nicholay and Hay referenced “’deep seated disaffection’ in New Jersey, shown by legislation and elsewise.” They also referenced the use of soldiers to enforce the draft in Detroit, Michigan, and put down draft resistance in Rutland, Vermont. There was constant contact between the States and members of the Lincoln Administration. “Governor Gilmore, of New Hampshire, wrote Secretary Stanton January 13th, 1864, of a clamor against the Government and that ‘Copperheads are jubilant.’” Their jubilation centered on the continued resistance to the draft.

John Codman Ropes, the Massachusetts lawyer, writer, and eulogizer of Lincoln, recognized the underlying support for the South. He noted that Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri were still Union States, “yet the feeling of a considerable part of the people in those States in favor of the new movement was so strong…that the Southern cause received substantial aid from each of them.”

With multiple pockets of resistance in the North and the Border States, Lincoln set about suppressing his opposition. Union General Fremont, a staunch Republican, lamented, “The administration has managed the war for personal ends, and with incapacity and selfish disregard of Constitutional rights, with violation of personal liberty of the press.”

Just a few weeks into the war, on April 27, 1861, Lincoln suspended the writ of habeas corpus, depriving his opposition of their most basic rights. This was soon followed by the program of shutting down newspapers and, finally, the call for more troops to invade the seceded States. No stone was left unturned as the Union war machine readied to coerce the seceded States.

Suppression of newspapers generally worked hand-in-hand with draft resistance. As the war progressed, and it became clear the Union would subdue the seceded States, there was a corresponding decline in dissent. Ever the politician, Lincoln and his minions silenced critics, as they felt necessary to advance their agenda.