Many years ago the historian Francis Parkman wrote a passage in one of his narratives which impresses me as full of wisdom and prophecy. After a brilliant characterization of the colonies as they existed on the eve of the Revolution, he said, “The essential antagonism of Virginia and New England was afterwards to become, and to remain, an element of the first influence in American history. Each might have learned much from the other, but neither did so til, at last, the strife of their contending principles shook the continent.” If we take Virginia as representing the South and New England as representing the North, as I think we may fairly do, we can say that this situation continues in some degree down to the present. Each section had much to learn from the other: neither was willing to learn anything and that failure produced 100 years ago the greatest tragedy in American history. Today it appears in political friction, social resentment, and misunderstanding of motives despite encouraging signs of growing amity.

This amity will clearly depend upon an appreciation, which Parkman found so sadly lacking, of what each has to offer. You certainly never get anywhere in mutual understanding among peoples or nations by assuming in advance that the other fellow has nothing whatever to offer. We would never think of assuming that in the case of the English or the French or the Chinese, or even the American Indians. But I only report what I have observed if I say that there appears a tendency on the part of a good many Americans to assume that the American South has nothing to offer—nothing worth anybody’s considering. That is a proposition in itself, and it needs to be examined in the light of evidence.

My principal theme, therefore, will be those things the South believes it has contributed to this great, rich, and diversified nation and which it feels have some right to survive and to exert their proportionate influence upon our life.

Before I can do this, however, I shall have to say something about what the South is—what makes it a determinate thing, a political, cultural, and social entity, which by the settlement of 1865 is going to be part of the union indefinitely.

It is virtually

In dealing with the factors which have produced this unity of thought and feeling in the South, it seems best to take them in the order of their historical emergence.

The first step toward understanding the peculiarities of the Southern mind and temper is to recognize that the South, as compared with the North, has a European culture—not European in the mature or highly developed sense, but more European than that which grew up north of the Potomac and Ohio rivers, in several respects, even more European than that of New England.

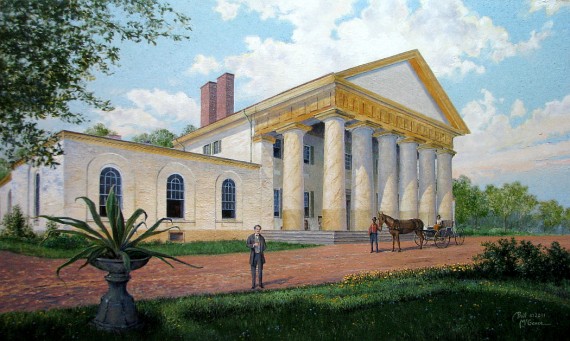

The South never showed the same interest in seceding from European culture that the North and West showed. It played an important and valiant part in the Revolution, but this was a political separation. After the Revolution it settled down quite comfortably with its institutions, modelled on eighteenth century England. A few stirrings of change, I believe, there were in Virginia, but not enough to alter the patterns of a landowning aristocracy. While Emerson in New England was declaiming, “We have listened too long to the courtly muses of Europe,” the South was contentedly reading Sir Walter Scott, not, as Russell Kirk has shrewdly pointed out in his The Conservative Mind, just because it liked romance but because in Sir Walter Scott it found the social ideals of Edmund Burke. And Burke is one of the great prophets of conservative society. The European complexion of Southern culture showed itself also in other ways. It showed itself in the preservation of a class society—one might more truly say in the creation of a class society—for very few who settled in the South had any real distinction of family. It appeared in the form of considerable ceremonial in dress and manners. It was manifested in the code duello, with all its melancholy consequences. It appeared in the tendency of Southern families who could afford it to send their sons to Europe for their education—even Edgar Allen Poe received some of his schooling in England. And it appeared in a consequential way in their habit of getting their silver, their china, their fine furniture and the other things that ornamented Southern mansions from Europe in exchange for their tobacco, cotton and indigo.

Whether the South was right or wrong in preserving so much of the European pattern is obviously a question of vast implications which we cannot go into here. But I think it can be set down as one fact in the growing breach between South and North. The South retained an outlook which was characteristically European while the North was developing in a direction away from this—was becoming more American, you might say.

There are evidences of this surviving into the present. A few decades ago when Southern Rhodes scholars first began going to England, some of them were heard to remark that the society they found over there was much like the society they had left behind. England hardly seemed to them a foreign country. This led to attempts by some of them to reassert the close identity of Southern and Western European culture, to which I expect to refer again later.

The second great factor in the molding of Southern unity and self-consciousness was the Civil War. Southerners are sometimes accused of knowing too much about the Civil War, of talking too much about it, of being unwilling to forget it. But there are several reasons why this rent looms very large in the Southerner’s memory, and why he has little reluctance in referring to this war, although it was a contest in which he was defeated.

To begin with, Southerners, or the great majority of them, always have believed that their part in this war was an honorable one. Far from regarding themselves as rebels, they felt that they were loyal to the original government, that is to say, they believed that they were fighting to defend the government as it was laid down at Philadelphia in 1787 and as recognized by various state ordinances of ratification. This was a government of restricted power, commissioned to do certain things which the states could not do for themselves, but strictly defined as to its authority. The theory of states’ rights was a kind of political distributism which opposed the idea of a powerful centralized government. The Southern theory then as now favored the maximum amount of self-determination by the states and it included, as a kind of final guarantee that states’ rights would be respected, the principle of state sovereignty, with its implied right of secession.

In the Southern view, it was the North that was rebelling against this idea which had been accepted by the members of the Constitutional Convention in 1787. Or to put it in another way, the North was staging a revolution, the purpose of which was to do away with this older concept of the American government. The South refused to go along with the revolution, invoked the legal safeguards which it believed to exist, and then prepared to defend itself by force. You may recall that the late historian Charles A. Beard found enough substance in this to call the Civil War “the Second American Revolution” in his Rise of American Civilization. Thus in this second American Revolution the Northerners were in the role of patriots, the Southerners in the role of English, if we keep our analogy with the Revolutionary War.

In all great crises of history where you have a legal principle challenged by a moral right, you find people flocking to both standards. The one side says it believes in the duty of upholding the law. The other side says it believes in the imperative necessity of change, even at the expense of revolution. Though the Civil War may not look quite so simple to us now, this is the way many people saw it. A number of years ago, Gerald Johnson wrote an ingenious little book on Southern secession, in which he referred to it as the struggle between the law and the prophets. The South had the law and the North had the prophets, in the form of the abolitionists and also of the advocators, both heard and unheard, of a strong central government, unimpeded by theories of states’ rights.

The legal aspects of an issue which has been so long decided can now have only academic interest. But if any of you wish to see a statement of the South’s legal position on state sovereignty and secession, the best source is a little book by a man named Bledsoe—A. T. Bledsoe—Is Davis A Traitor? Bledsoe was a Kentuckian, and he brought to the task of writing this defense an interesting set of qualifications. He was a lawyer, a professor of mathematics, and for ten years he had been a colleague of Lincoln at the bar of Springfield. Also—and probably this is pertinent to mention, since we are talking here about a metaphysical debate—he had written a book-length refutation of Jonathan Edwards’ Freedom of the Will. I do not know whether this is true or not, but it has been said that the appearance of Is Davis A Traitor? in 1866, was one of the things that made the North decide not to bring Davis to trial. At any rate, the failure to bring Davis to trial was naturally taken by the South as a sign that the North’s legal case was too weak to be risked in court.

These are the chief things causing Southerners to feel that, whatever the claims of moral right and wrong, they had the law on their side.

Now we come to the fact of the Civil War itself. It was impossible that a struggle as long and bitter as this should not leave deep scars. Americans, particularly those of the present generation, are prone to forget the magnitude of this civil conflict. The United States lost more men from battle wounds and disease in the Civil War than in any other war of its history, including the Second World War. The battle front stretched from Pennsylvania to New Mexico, and included also the seven seas. A good many of the wars of history have been decided by two or three major battles. In our Civil War at least eighteen battles must be accounted major by reason of the number and resources involved. The minor battles run into scores, and the total number of engagements—somebody once counted them up—is as I recall, something more than 2200. Of this eighteen major battles you might call five or six “critical” in a sense that, with a more decisive result, they might have ended the war right there or have turned it in favor of the side which eventually lost. I would include in my list of critical battles Shiloh, the Seven Days, Sharpsburg, Gettysburg, and Chickamauga. So you can see it was really a knock-down drag-out fight.

There is a further fact to be noticed in discussing the effect of this war. Nearly the whole of it was fought on Southern soil. With the exception of the Gettysburg campaign, and John Hunt Morgan’s raids into Indiana and Ohio, and the small but famous St. Albans raid in Vermont—a group of Confederates in disguise came down from Canada, shot up the little town of St. Albans in Vermont, took the bank deposits and got back across the border—the North was physically untouched. There is a great difference between reading about a war your boys are fighting 500 miles away, and having the war in your midst, with homes being burned, farms being stripped, and your institutions being pulled to pieces. I’ll bet any Japanese or German today will testify to this. The war was much more a reality to the people of the South than to those of the North, and it has remained such down to the present.

A natural question to come up at this point is, why should anybody care to remember or write histories about a war which left his country a hollow shell? In order to explain this, I shall have to tell you something else from the Southern credo, something that goes along with this faith in the legal case. It has been a prime factor in preserving Southern morale and in maintaining that united front of the South which I am afraid has been such a vexation to the rest of the country. And the only way I can really tell this is by an anecdote, even though I have to explain the anecdote.

The story goes that a ragged Confederate soldier was trudging his way home from Appomattox. As he was passing through some town, somebody called out to him by way of taunting. “What’ll you do if the Yankees get after you?” And his answer was, “They aren’t going to bother me. If they do, I’ll just whip ’em again.” The point of the anecdote, which may need to be explained, is that the answer was at least half serious. It was a settled article of belief with the Southern soldiers—echoed in numberless Confederate reunions—that although they had lost the war, they had won the fighting—that individually they had proved themselves the equal, if not the superior of their adversary and that the contest had finally been decided by numbers. There is no point in going into the merits of the argument here. But it is easy to see how, right or wrong, it had a great effect in preserving Southern pride, and even in maintaining a spirit of defiance which to this day characterizes a good bit of Southern policy.

It also helps to explain why the South has written so voluminously about the war, and why in libraries today, for example, you can find a biography of practically every Confederate General of any eminence whatever, and sometimes three or four. A quick check of the card files in Harper library reveals ten full-length biographies of William Tecumseh Sherman, but fourteen of Stonewall Jackson, plus biographies of Stoneman, Pleasanton, Grierson, Bedford, Forrest, Stuart, and a definitive biography of Lee by D. S. Freeman; but no definitive biography of Grant. The remark has been made that in the Civil War the North reaped the victory and the South the glory. If you consult the literature of the subject very extensively you find a certain amount of truth in that.

Evidently there was enough substance in the legend to nourish the martial tradition of the South, and to support institutions like VMI, the Citadel and the A & M College of Texas, which do not have counterparts in other sections of the country.

This brings the story down to Reconstruction; which somebody has described as “a chamber of horrors into which no good American would care to look.” If that is an exaggeration, it still seems fair to say that this was the most dismal period of our history—a bitter, thirty-year sectional feud in which one side was trying to impose its will on the other, and the other was resisting that imposition with every device of policy, stratagem and chicanery that could be found. We must realize that no people willingly accepts the idea of being reconstructed in the image of another. That is, in fact, the ultimate in humiliation, the suggestion that you must give up your mind, your inherited beliefs and you way of life in favor of that of your invaders. There was a critical period when, if things had been managed a little worse, the South might have turned into a Poland or an Ireland, which is to say a hopelessly alienated and embittered province, willing to carry on a struggle for decades or even centuries to achieve a final self-determination. That was largely forestalled by the wisdom of a few Northern leaders. The work of Lincoln toward reconciliation is well known but that of Grant, at Appomattox and also later, I think has never been sufficiently appreciated. And the act of Lee in calling for reunion once the verdict of battle has been given was of course of very great influence.

It was an immeasurable calamity that Lincoln was not allowed to live and carry out his words in the lofty and magnanimous spirit which his speeches reflect. He was himself a product of the two sections, a Kentuckian by birth, an Illinoisian by adoption. He understood what had gone into the making of both. As it was, things were done which produced only rancor, and made it difficult for either side to believe in the good faith of the other. It is unfortunate but it is true that the Negro was forced to pay a large part of the bill for the follies of Reconstruction.

By all civilized standards the period was dreadful enough. George Fordt Milton has called his history covering those years The Age of Hate. Claude Bowers has called this The Tragic Era. If you desire a detailed account of what the South experienced in these years probably the best source to go to is Why the Solid South, Reconstruction and Its Results, (ed. Hilary Herbert) by a group of Southern leaders, including a number of governors of states. This is of course, a Southern view, but it tells you from the inside something about the financial, political, and social chaos that prevailed in those years.

Unquestionably Reconstruction did something to deepen the self-consciousness of the Southern people, to make them feel less American rather than more so. They became the first Americans ever to be subject to invasion, conquest, and military dictation. In estimating the Southern mind it is most important to realize that no other section of America has been through this kind of experience. In fact it is not supposed to be part of the American story. The American presents himself to the world as ever progressing, ever victorious, and irresistible. The American of the South cannot do this. He has tasted what no good American is supposed ever to have tasted, namely the cup of defeat. Of course, that experience is known to practically all the peoples of Europe and of Asia. This circumstance has the effect of making the mentality of the Southerner again a foreign mentality—or a mentality which he shares in respect to this experience with most of the peoples of the world but does not share with the victorious American of the North and West. He is an outsider in his own country. I have often felt that the cynicism and Old-World pessimism which the rest of the country sometimes complains of in the South stems chiefly from this cause. The Southerner is like a person who has lost his innocence in the midst of persons who have not. William A. Percy, going from a plantation on the Mississippi Delta to the Harvard Law School found that Northern boys were “mentally more disciplined” but “morally more innocent” than Southern boys. His presence is somehow anomalous; he didn’t belong.

It is sometimes said, with reference to these facts, that the South is the only section of the nation which knows the meaning of tragedy. I am inclined to accept that observation as true and to feel that important things can be deduced from it. Perhaps there is nothing in the world as truly educative as tragedy. Tragedy is a kind of ultimate. When you have known it, you’ve known the worst, and probably also you have had a glimpse of the mystery of things. And if this is so, we may infer that there is nothing which educates or matures a man or a people in the way that the experience of tragedy does. Its lessons, though usually indescribable, are poignant and long remembered. A year or so ago I had the temerity to suggest in an article that although the South might not be the best educated section in the United States, it is the most educated—meaning that it has an education in tragedy with which other educations are not to be compared, if you are talking about realities. In this sense, a one-gallon farmer from Georgia, sitting on a rail fence with a straw in his mouth and commenting shrewdly on the ways of God and man—a figure I adopt from John Crowe Ransom—is more educated than say a salesman in Detroit, who has never seen any reason to believe that progress is not self-moving, necessary and eternal. It would seem the very perverseness of human nature for one to be proud of this kind of education. But I do believe it is a factor in the peculiar pride of the Southerner. He has been through it; he knows; the others are still living in their fool’s paradise of thinking they can never be defeated. All in all, it has proved difficult to sell the South on the idea that it is ignorant.

In a speech made around the turn of the century, Charles Aycock of North Carolina met the charge of ignorance in a way that is characteristic in its defiance. Speaking on “The Genius of North Carolina Interpreted,” he said,

Illiterate we have been, but ignorant never. Books we have not known, but men we have learned, and God we have sought to find out.

[North Carolina has] nowhere within her borders a man known out of his township ignorant enough to join with the fool in saying “There is not God.”

You will note here the distinction made between literacy and knowledge—a distinction which seems to be coming back into vogue. You will observe also the preference of knowledge of men over knowledge of books—this is where our Southern politicians get their wiliness. And you will note finally the strong emphasis upon religiosity.

(It has also been claimed that this tragic awareness perhaps together with the religiosity is responsible for the great literary productiveness of the South today. That is a most interesting thesis to examine, but it is a subject for a different lecture.)

For a preliminary, this has been rather long, but I have felt it essential to present the South as a concrete historical reality. One of the things that has prevented a better understanding between North and South, in my firm belief, is that to the North the South has never seemed quite real. It has seemed like something out of fiction, or out of that department of fiction called romance. So many of its features are violent, picturesque, extravagant. With its survivals of the medieval synthesis, its manners that recall bygone eras, its stark social cleavages, its lost cause, its duels, its mountain flask, its romantic and sentimental songs, it appears more like a realm of fable than a geographical quarter of these United States. Expressed in the refrain of a popular song, “Is It True What They Say About Dixie,” the thought seems to be that the South is a kind of

I shall begin by saying something about the attitude toward nature. This is a matter so basic to one’s outlook or philosophy of life that we often tend to overlook it. Yet if we do overlook it, we find there are many things coming later which we cannot straighten out.

Here the attitudes of Southerners and Northerners, taken in their most representative form, differ in an important respect. The Southerner tends to look upon nature as something which is given and something which is finally inscrutable. This is equivalent to saying that he looks upon it as the creation of a Creator. There follows from this attitude an important deduction, which is that man has a duty of veneration toward nature and the natural. Nature is not something to be fought, conquered and changed according to any human whims. To some extent, of course, it has to be used. But what man should seek in regard to nature is not a complete dominion but a modus vivendi—that is, a manner of living together, a coming to terms with something that was here before our time and will be here after it. The important corollary of this doctrine, it seems to me, is that man is not the lord of creation, with an omnipotent will, but a part of creation, with limitations, who ought to observe a decent humility in the face of the inscrutable.

The Northern attitude, if I interpret it correctly, goes much further toward making man the center of significance and the master of nature. Nature is frequently spoken of as something to be overcome. And man’s well-being is often equated with how extensively he is able to change nature. Nature is sometimes thought of as an impediment to be got out of the way. This attitude has increasingly characterized the thinking of the Western world since the Enlightenment, and here again, some people will say that the South is behind the times, or even that it here is an element of the superstitious in this regard for nature in its originally given form. But however you account for the attitude, you will have to agree that it can have an important bearing upon one’s theory of life and conduct. And nowhere is its influence more decisive than in the corollary attitude one takes toward “Progress.”

One of the most widely received generalizations in this country is that the South is the “unprogressive section.” If it is understood in the terms in which it is made, the charge is true. What is not generally understood, however, is that this failure to keep up with the march of progress is not wholly a matter of comparative poverty, comparative illiteracy, and a hot climate which discourages activity. Some of it is due to a philosophical opposition to Progress as it has been spelled out by industrial civilization. It is an opposition which stems from a different conception of man’s proper role in life.

This is the kind of thing one would expect to find in those out-of-the-way countries in Europe called “unspoiled,” but it is not the kind of thing one would expect to find in America. Therefore I feel I should tell you a little more about it. Back about 1930, at a time when this nation was passing through an extraordinary sequence of boom, bust, and fizzle there appeared a collection of essays bearing the title I’ll Take My Stand.1 The nature of this title, together with certain things contained, caused many people to view this as a reappearance of the old rebel yell. There were, however, certain differences. For one thing, the yell was this time issuing from academic halls, most of the contributors being affiliated in one way or another with Vanderbilt University. For another, the book did not concentrate upon past grievances, as I am afraid most Southern polemic has done, but rather upon present concerns. Its chief question was, where is industrialism going anyhow, and what are its gifts, once you look them in the mouth? This book has since become famous as “The Agrarian Manifesto.” As far as content goes, I think it can fairly be styled a critique of progress, as that word is used in the vocabulary of modern publicity and boosting.

Although the indictment was made with many historical and social applications, the center of it was philosophical; and the chief criticism was that progress propels man into an infinite development. Because it can never define its end, it is activity for the sake of activity, and it is making things so that you will be able to make more things. And regardless of how much of it you have, you are never any nearer your goal because there is no goal. It never sits down to contemplate, and ask, what is the good life? but rather assumes that material acquisition answers all questions. Language something like this was employed by John Crowe Ransom, one of the most eloquent of the spokesmen, in his chapter, “Reconstructed but Unregenerate.”

“Progress never defines its ultimate objective but thrusts its victims at once into an infinite series,” Mr. Ransom said. And he continued, “Our vast industrial machine, with its laboratory center of experimentation, and its far-flung organs of mass

Another cardinal point, touched on here and there in the volume, is the Southerner’s attachment to locality. The Southerner is a local person—to a degree unknown in other sections of the United States. You might say that he has lived by the principle that it is good for a man to have a local habitation and a name; it is still better when the two are coupled together. In olden days a good many Southerners tried to identify their names and their homes: thus we read in history of John Taylor of Caroline, of Charles Carroll of Carrollton; of Robert Carter of Nomini Hall; of the Careys of Careysbroke; of the Lees of Westmoreland County. With the near liquidation of the old land-owning aristocracy this kind of thing became too feudal and fancy to keep up. Nevertheless, something of it remains in a widespread way still; the Southerner always thinks of himself as being from somewhere, as belonging to some spot of earth. If he is of the lucky few, it may be to an estate or a plantation; if not that, to a county; and if not to a county at least to a state. He is a Virginian, or he is a Georgian in a sense that I have never encountered in the Middle West—though the Indiana Hoosiers may offer a fair approximation. Very often the mention of a name in an introduction will elicit the remark, “That is a Virginia name” or “That’s a South Carolina name,” whereupon there will occur an extensive genealogical discussion. Often this attachment to a locale will be accompanied by a minute geographical and historical knowledge of the region,

The pride of local attachment is a fact which has two sides; it is a vice and a virtue. It may lead to conceit, complacency, and ignorance of the world outside. It frequently does lead to an exaggerated estimate of the qualities and potentialities of the particular region or province. The nation as a whole is acquainted with it in the case of Texans, who have developed this Southern attribute in an extreme degree. I was teaching out in Texas about the time we were ending the Second World War. A jocular remark that was passed around with relish was: “I know we are going to win the war now. Texas is on our side.” It was a fair gibe at Texan conceit.

But on the other side, provincialism is a positive force, which we ought to think about a long while before we sacrifice too much to political abstractionism. In the last analysis, provincialism is your belief in yourself, in your neighborhood, in your reality. It is patriotism without belligerence. Convincing cases have been made to show that all great art is provincial in the sense of reflecting a place, a time, and a Zeitgeist. Quite a number of spokesmen have pleaded with the South not to give up her provincialism. Henry Watterson, a long-time editor of the Louisville Courier Journal, told an audience of Kentuckians, “The provincial spirit, which is dismissed from polite society in a half-sneering, half-condemnatory way is really one of the forces of human achievement. As a man loses his provincialism he loses, in part, his originality and, in this way, so much of his power as proceeds from his originality.” He spoke caustically of “a miserable cosmopolitan frivolity stealing over the strong simple realism of by-gone times.” He summed up by asking, “What is life to me if I gain the whole world and lose my province?”

Thirty years later Stark Young, writing in the agrarian manifesto to which I referred earlier, pursued the same theme. “Provincialism that is a mere ramification of some insistent egotism is only less nauseous than the same egotism in its purity . . . without any province to harp on. But provincialism proper is a fine trait. It is akin to a man’s interest in his own center, which is the most deeply rooted consideration that he has, the source of his direction, health and soul. . . . People who give up their own land too readily need careful weighing, exactly as do those who are so with their convictions.”5 What often looks like the Southerners’ unreasoning loyalty to the South as a place has in this way been given some reasoned defense. Even Solomon said that the eyes of a fool are in the ends of the earth. One gives up the part for the whole only to discover that without parts there is no whole. But I have said enough about the cultural ideal of regionalism. If you would be interested in a book which brings these thoughts together in a systematic treatment, see Donald Davidson’s The Attack on Leviathan.

Despite what I have said about this love for the particular, which is another name for love of the concrete, the Southern mind is not by habit analytical. In

With some of these specific protests I would gladly agree, yet there is perhaps another light in which we can see this “unyielding stability of opinion.” Stability has its uses, as every considerate man knows, and it is not too far-fetched to think of the South as the fly-wheel of the American nation. A fly-wheel is defined by the science of mechanics as a large wheel, revolving at a uniform rate, the function of which is to stabilize the speed of the machine, slowing it down if it begins to go too fast and speeding it up if it begins to go too slow. This function it performs through the physical force of inertia. There are certain ways in which the South has acted as a fly-wheel in our society. It has slowed down social change when that started moving rapidly. And, though this will surprise many people, it has speeded up some changes when change was going slowly. Without judging the political wisdom of these matters, I merely point out that without Southern order, the New Deal probably would have foundered. Without Southern votes, the Conscription act would not have been renewed in 1941. Generally speaking the South has always been the free trade section. It is not very romantic or very flattering to be given credit only for inertia. But conservatism is not always a matter of just being behind. Sometimes conservatives are in the lead. I could give you more examples of that if I had time. It requires little gathering up of thread to show that a mind produced by this heritage is diametrically opposed to communism. With its individualism, its belief in personality, its dislike of centralized government, and its religiosity, the South sees in the communist philosophy a combination of all it detests. If that issue comes to a showdown, which I hope does not happen, there will never be any doubt as to where the South stands.

I suspect that a good many of you entertain thoughts of changing the South, of making it just like the rest of the country, of seeing it “wake up.” It seems to me that the South has been just on the verge of “waking up” ever since I have been reading things about it. My advice is to be modest in your hopes. The South is one of those entities to which one can apply the French saying, “the more it changes the more it remains the same.” Even where you think you are making some headway, you may be only heading into quicksand. It waits until you are far enough in and then sucks you under. It is well to remember that the South is very proud of its past, hard as it has been; it does not want to be made over in anybody else’s image, and it has had a century of experience in fighting changes urged on it from the outside. I agree with W. J. Cash that the Southern mind is one of the most intransigent on earth; that is, one of the hardest minds to change. Ridiculing its beliefs has no more effect, as far as I have been able to observe, than ridiculing a person’s religious beliefs—and the Southerner’s beliefs have been a kind of secular religion with him: that only serves to convince him further that he is right and that you are damned.

Intransigence in itself, however, is not good, of course. No mind ought to be impervious to suggestions and the influence of outside example. Intercommunication and

Originally published in The New Individualist Review, Vol. 3, No. 3 (7-17).