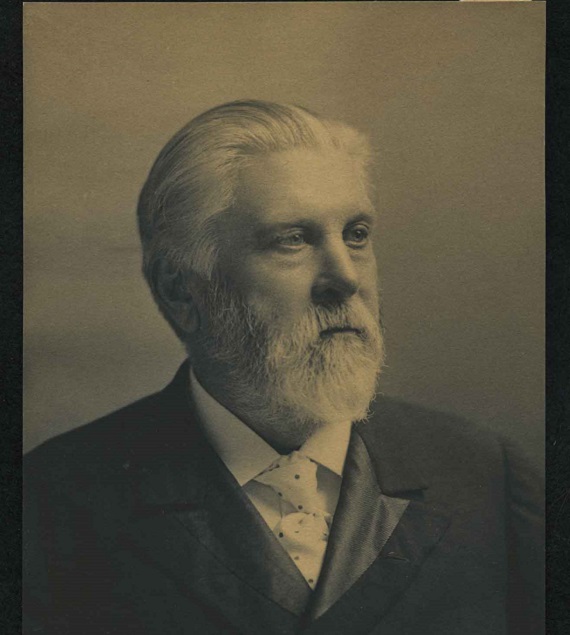

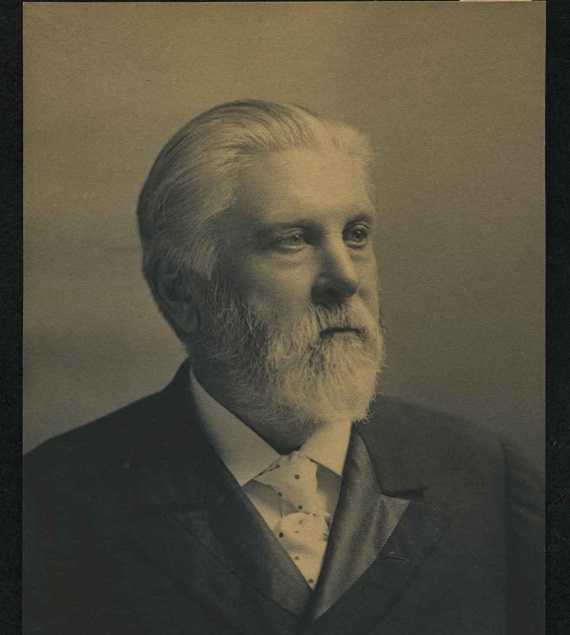

Jabez Lafayette Monroe Curry was one of the major political figures of the Old South. In the Alabama Assembly and the United States Congress, he was a passionate and articulate advocate for state sovereignty limited government and a strict construction of the Constitution.

With the creation of the Confederacy, he helped draft its new constitution and design its “stars and bars” flag, and was a member of its Congress.

Then came the War for Southern Independence. Curry was a staff officer with General Joseph E. Johnston during the long, bloody retreat toward Atlanta. Later he took command of the 5th Alabama Cavalry Regiment, fighting to the end with such great men as Joe Wheeler and Nathan Bedford Forrest.

After the surrender, the Union government considered Jabez Curry one of the principal “traitors” of the “rebellion.” He faced possible execution. Jabez pled his case personally before President Andrew Johnson. They had been close friends in Congress before the war. Johnson pardoned Curry but the terms were severe. All his property was confiscated. He swore never to enter politics again. He had been a lawyer but now he could never practice that profession again. Curry could never speak or write about the issues that he fought for.

Just before the terms of his pardon went into effect, Jabez Curry made one final political speech. As always he was passionate but now his words were tragic and cynical, and he gave the first hint of the need to continue the struggle by other means: “The country has been impoverished. Our political institutions have been revolutionized; our peculiar civilization destroyed; our cherished theories of government overthrown. We are no longer the peculiar people, the conservator of constitutional liberty, the resisters of the encroachment of power, the preservers of ancient forms, which include justice and freedom.” Then Jabez added a final note that was totally out of character for this fiery statesman and warrior. He seemed to give up, to accept the unacceptable. Or was he throwing the conquerers off his trail and preparing for guerilla war? “We must accept these and all other legitimate facts as they are; acquiesce in them; offer loyal homage and obedience to the only government we have.”

Guerilla War from the Pulpit

Soon Jabez Curry showed what his words really meant. He had found a way to continue the struggle by his form of guerilla war. By the terms of his pardon he could not earn a living by any of the ways he had in the past. So, he went to a Baptist divinity college and emerged as the Reverend Curry, but by his own admission he was not a very religious man: “In my youth I had no distinctive impressions or convictions. Of the Bible, I was stupidly ignorant. I had no convictions of sin, no desire for salvation. I have never had any rapturous experiences. I have often wished and prayed for the experiences that some Christians have; but they have been denied me, or possibly by unbelief I have denied them to myself.” Yet, the ministry was a way to fight on by clandestine means as well as a way to make a living.

Because of his prestige, Jabez Curry was soon in great demand and he preached all over the South. Once again he could speak in public and excite his listeners. Now it seemed to be about God and salvation, not the ideals of the Lost Cause. Or was it?

While Washington was satisfied that Jabez was living up to the terms of his oath, he kept the old ideals alive to the new generation of Southerners chafing under carpetbag rule, by preaching and writing by parable.

Fusing England’s Church and State or the South’s?

Curry wrote and spoke about the painful history of the Baptists in England and colonial America, beginning in the 1600s, when the British government had fused with the Anglican Church and “established” it as the Church of England, the only official body. The situation that Curry depicted paralleled the State religion created by Washington in the former Confederacy.

Many carpetbaggers held the deluded dream to “impregnate the South with Northern ideals and civilization.” They enlisted the brute force of the military to actualize this dream. The army confiscated Southern churches and the properties of many Baptist, Methodist and Presbyterian congregations. Their ministers were called traitors and Northern preachers were installed at bayonet point. The Federal government paid for their salaries and built new churches.

All this was unconstitutional. It fused Church to State. As a result, these subsidized churches became governmental bureaucracies, promoting Radical Republican policies. “Every innovation of the Executive [the President] was adopted as an article of faith.”

All this represented a more centralized, despotic State to Jabez Curry, so he wrote two books based on his sermons and articles in Baptist publications. In Establishment and Disestablishment, Curry detailed the entire history of the Christian religion and its entrapment and fusion with civil government, from its earliest roots in the Roman Empire, in Struggles and Triumphs of Virginia Baptists, he focused on religious persecutions in colonial Virginia and how the Baptists severed their relationship with the government of Great Britain.

In both cases, Curry was describing crimes of centuries before, but in reality they were the same horrors against his own occupied South. The examples of how colonial Virginia broke its religious ties to the State provided a model of how the South could do the same: “Christianity has often been allied with civil government. Since the third century of the Christian era such a connection was made. Such a theory was induced in part, by the fact that, under the Old Covenant, a theocracy existed, and the civil government was instituted, to a large degree, to maintain and foster religion. Civil rulers, for self-aggrandizement, subordinated Christianity, or rather ecclesiastical organizations, to their corrupt purposes. When Church and State are united, the State practically assumes infallibility and the right to sit in judgment upon creeds, and to determine what is a church, what is true and what is false religion.”

Curry added: “An Establishment fosters notions of arbitrary government, cultivates opposition to liberal principles. The pulpit often reflects the caprice and will and cause of the court. The advocates of divine right of kings, of passive obedience, the opponents of revolution, of civil reform, of popular liberty, have uniformly been the adherents of the Establishment. The rightness of a union of Church and State, by an inevitable logic, leads to the rightness of Absolutism, of despotism, to the denial of individual liberty.”

The following sketch of colonial Virginia parallels the Reconstruction South, where State, Army and Church merged, and where Northern clergymen became dissolute from power and moneymadness: “The sufferings and virtues of these noble men and women aroused popular sympathy in their behalf and drew attention to the tyranny and wickedness of the Establishment. Popular displeasure, thus generated, was increased by the notoriously inconsistent and dissolute lives of many of the clergy, an inseparable consequence of a legal Establishment. The opposition was not lessened when clergymen, greedy and exacting in the collection of tithes, resorted to the courts to compel payment from reluctant and straitened parishioners. It was intensified into hostility when, in the struggle for independence, the State clergy were generally friends of the Mother Country.”

The Sedition Laws of the 1600s in England corresponded to the Reconstruction “Force Laws,” where the gathering together of three or more people constituted a conspiracy. Curry wrote: “In 1664 a law was passed for the suppression of seditious conventicles [religious assembly], which inflicted on all persons, over sixteen years of age, present at any religious meeting of five or more persons in any manner other than is allowed by the practice of the Church of England, a penalty of three months imprisonment for the first offense, of six months for the second, and seven years transportation [deportation] for the third. If the offender returned, he was doomed to death.”

Here Curry attacks the Roman Church but his ideas are just as appropriate for Washington’s omniscience when it came to the South: “There is a strong tendency in individuals, sects and parties to arrogate superior wisdom and to condemn dissenters for not accepting their judgements. This is a kind of Sir Oracle presumption. ‘When I open my mouth, let no dog bark.’ We are accustomed to having sections assume a kind of exclusive patriotism and devotion to human rights. Men often boast of their liberty of conscience, freedom of thought, but are reluctant to concede the same privileges to others. With certain people, ‘the church’ is used to signify their special communion, including a class of the select or the superior, and excluding ‘the masses,’ the ‘great unwashed.’”

In Establishment and Disestablishment Curry wrote about how in 18th century England, religious tests were required of the colonial clergy to demonstrate loyalty to the Crown. This had a parallel in post-war Dixie, where test oaths were used to disqualify ex-Confederates from political, religious and legal positions. Curry: “In the matter of religious tests the Mother Country claimed to control the colonies. Bigoted feeling under Queen Anne was strong, and in 1702 she issued an order directing that all those who held any public office in any colony, whether the colony was royal, chartered or proprietary, should take the tests and make declarations required by the Imperial Toleration Act.”

Volatile American and Spanish Constitutions

Even twenty years after the war, Southerners were still considered traitors and still largely barred from nationally prominent political positions. They still had to be careful about what they said or wrote in public. Then President Grover Cleveland appointed Jabez Curry Ambassador to Spain in 1885. This was considered a peace offering to the South.

Later, in Constitutional Government in Spain, Curry wrote about his experiences in Madrid, including the numerous Spanish constitutions, which produced instability and violence. His story was just as applicable to the tragic volatility that Reconstruction had produced in the United States, after the War for Southern Independence. This new American document was the antithesis of the original. Instead of promoting State Sovereignty, it destroyed it. Instead of insuring a decentralized government, it opened the way for a nationalized one. Instead of insuring government by the people, this new constitution was put in place against the will of many Southern and Northern voters. Curry wrote: “The American idea of the derivation of political power from the people has not found lodgement, as an actuality, in Spanish politics, literature or thought. Absolute monarchy, a regency, military dictatorship, have come and gone with suddenness and celerity. Militarism, flagrant violations of constitutions and alas, oscillations between despotism and anarchy, have marked the unhappy history of this country and the people have often quietly acquiesced in these rapidly occur- ring mutations as things to be expected. Power has been sought, not by legal methods or constitutional forms, but by revolts, insurrections, conspiracies. The bayonet has superseded the ballot box or the vote of the Cortes. The army has been a political machine. Military officers, intriguers. In the crisis of every party question, the inquiry is, ‘which side controls the cannons?”

England vs. Ireland or Southern Disfranchisement

Jabez Curry wrote a biography ’ of Britain’s famed Prime Minister, William Gladstone. The reforms that Gladstone introduced, to normalize the antagonistic relations between Ireland and England, reflected the way Curry wished that Washington would deal with the South during the hostile decades following the war. The “Irish Question” was analogous to the “Southern Question.” Curry wrote: “Ireland is a paradox. It is claimed that rules and motives applicable to other peoples cannot be adjusted to the Irish. The North and South do not harmonize. Catholics and Protestants are like alien races. Hates and antipathies rather than friendships and agreements have dominated. Loyalty, law and order, intelligible terms, have been misapplied. Loyalty to the sovereign and imperial patriotism have been the exception. Secret leagues have taken the place of open political warfare. Assassinations, boycotting, proscription, absenteeism, governmental distrust, oppressive discrimination, coercion, shadowing, have been varying aspects of the mobile kaleidoscope.”

Local control vs. nationalized government was a major issue for the Irish as well as the South: “Home rule has been much misrepresented, and Gladstone has been fiercely assailed for his willingness to sever the Empire by making Ireland independent. His proposal is Imperial unity with local autonomy. He once forcibly said that centralization ‘throws upon the English Parliament and English officials the duty and burden of supervising every petty detail of Irish local affairs, stifles the national life, destroys the sense of responsibility, keeps the people in ignorance of the duties and functions of government, produces a perpetual feeling of irritation, while it obstructs all necessary legislation.”

This piece was originally published in the Jan/Feb 2009 issue of Southern Partisan magazine.