Many who are well acquainted with Southern history are almost entirely unfamiliar with the historical character of Nathaniel Macon. He is often mentioned by the best of authors as a North Carolinian, as a Georgian, or simply as a Southern Democrat. His share in the political development of the South is but vaguely known, yet every southern state has either a town or a county, or both, called by his name. The reason of his passing so entirely out of the minds of men is twofold : first, Southerners have not been students of history ; second, Macon himself ordered all his papers burned before his death. The somewhat erratic old leader was determined to cover up his tracks, and he very nearly succeeded.

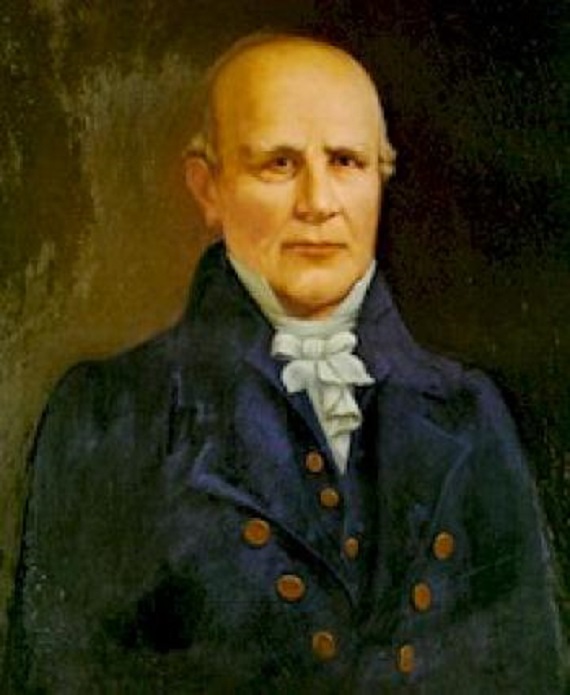

Nathaniel Macon was born at the “ Macon manor,” in Warren county, North Carolina, December 17, 1758. He was descended from a Huguenot family which had been ennobled, we are told, in 1321. A branch of the family came to America in 1680, settled near Middle Plantation in Virginia and was soon reckoned among the first families of the province.2 In the early thirties Nathaniel’s father emigrated to North Carolina and before 1760 he had become one of the wealthiest men in the “Southside of Roanoke.” The elder Macon was to upper North Carolina what the elder Jefferson was to northern Virginia—subduer of the forest and Indian fighter, a sort of Markgraf, ready always for an arduous undertaking. Young Macon, like young Jefferson, was left an orphan at a tender age and with a fair fortune. He was sent to Princeton, where so many young Southerners were then preparing themselves for the coming crisis. At college Macon “served a tour” in the Revolutionary army, but he returned in the autumn of 1776 to North Carolina, where he occupied himself for three years in the study of law and history. Two days before the fall of Charleston he joined a company of volunteers from Warren county and was elected a lieutenant ; he declined the honor, however, preferring to serve as a private. His company was at Camden, and was one of the few companies which maintained a show of order and appeared ready for service on the Yadkin a few days later. From February, 1781, to December, 1785, Macon was in the state legislature as Senator from Warren ; he was identified with the Willie Jones democracy as against the aristocratic party of the east under Johnston, Hooper and Iredell; in 1786 he was elected a delegate to the Continental Congress and was “ordered” to New York by the governor, but like Willie Jones in this, he disobeyed the order—he was opposed to the sending of delegates by the state to the old Congress. The new national Constitution met his determined opposition; yet in 1791 he appeared in Philadelphia as a member of the House of Representatives from North Carolina, where he remained without interruption until 1815, when he was transferred to the Senate. No one ever attempted to defeat his election to the Senate, and he therefore remained in office until he retired of his own accord, nominating his successor. From 1828 to 1837 he lived in secluded retirement on his plantation twelve miles north of Warrenton and two miles south of the Roanoke. In 1835 he served as chairman of the convention which gave North Carolina its second constitution. One year later he manifested great interest in the election of the Van Buren ticket and rejoiced in the triumph of his candidate. He died June 28, 1837, and was buried on the most barren hilltop of his large plantation. A huge pile of flint rock, surrounded by scrubby post oaks, now marks the spot.

Such is a brief outline of Macon’s public life. I wish now to point out the political policies of his career and his influence in getting these policies incorporated into the political creed of the South.

When the Revolution drew to a close the prominent leaders of the old regime in North Carolina began to assert themselves again in state politics. They had been excluded from active participation in public affairs by -two considerations: (1) a too zealous interest in the American cause would in case of ultimate defeat bring utter ruin upon them and their families; (2) the radicals, sansculottes as they were later called, were in the saddle and looked askance at the wealthy conservatives who were constantly decrying all republican forms of government and especially the more democratic. The leaders of the conservatives when their organized efforts began to be felt a second time were Johnston and Hooper, already referred to, both of whom were closely connected with prominent royalists? The leader of the radicals and the virtual dictator of the state was Willie Jones, a wealthy planter who lived like a prince but who talked and voted like a Jacobin. Those that had stood aloof from the Revolution, merchants of the eastern towns and many of the Tories, joined the conservatives in 1782-1785, and these elements forming a compact and powerful party were desirous of substituting a strong national government for the old royal regime, an idea which gave promise of some check to the power of the state which was then in the hands of their political opponents. The exiles or emigres naturally looked to these Nationals for protection against the angry state leaders, and with the promise of such aid, they came back to their estates. The Radicals—Whigs, as Macon always insisted on calling them—were determined that the lukewarm leaders of the Revolution and their new allies, the Tories, should not acquire the ascendency. A harsh confiscation law was directed against all who had taken any part in the British cause or whose conduct during the war had been open to serious question. And since the entire machinery of the state government was in the control of the latter party it was but natural that they should continue to exalt the state and decry every attempt of their opponents to form a “more permanent union of all the states.’’ The state was the creation of the Whigs; its enemies or detractors were little better to them than the Tories themselves.

Such was the division of parties in North Carolina and generally in the south, when Macon entered the legislature in 1781. He was by nature a radical: he joined the Jones party of which his brother was already a prominent leader. It was a sort of Virginian party after the Jefferson pattern of 1776; Jones and the Macons were themselves practically Virginians. They had given North Carolina a constitution in 1776 modeled after their mother state. Reform, democracy of the simplest type, were the ideas for which they stood. A most commendable item of their creed in this chaotic time was that which demanded a sound financial system based on gold and silver. This they could not carry into effect; but their earnest efforts did them great honor. It was a part of their scheme of state organization, and along with it they advocated protective tariff, public improvements, encouragement of foreign trade and intercourse and a better system of public education. The celebrated American policy of a later day was thus early put forward in North Carolina. In this school Macon served his apprenticeship and then retired at the age of twenty-seven to his new-made home near the Roanoke to observe the course of events. A call from this retirement to serve the state in the Continental Congress was not heeded, as has been seen. When the new Constitution was presented to North Carolina, he exerted himself to the utmost to defeat it. Its greatest opponents, Willie Jones and Thomas Person, were his friends and neighbors. All upper North Carolina, like all lower Virginia, was violently opposed to any plan of national union; the country which furnished the Revolution the greatest number of troops relative to population, and in which, it was boasted, scarce a single Tory lived, was in 1788 most determined in its opposition to all forms of nationalism. The whole broad area from Richmond to Raleigh and from Norfolk to Patrick Henry’s new home beyond Danville was staunchly Anti-federalist. Its older leaders were Henry and Jones ; its younger, Macon and John Randolph.

But when the Constitution was finally adopted, Macon re-entered politics and was among the first advocates of strict construction of the “contract” among the states. He soon became its champion, and it became to him a sort of fetich. The integrity of the state depended on the most rigid adherence to the letter of that instrument. In 1796-1798 he advocated increasing the militia of the states whenever the Federalists proposed increasing the army; the militia then and in 1807 was his sole dependence for national defense; its re-organization and complete equipment were perpetual themes with him. The principal charge of inconsistency ever brought against him was that of 1807-1808, when in the face of war with England he voted for an increase of six thousand men for the United States army. He opposed the Sedition Bill chiefly on the ground that it would encroach on the prerogative of the state. “Let the States,” said he, “continue to punish when necessary licentiousness of the press; how is it come to pass that Congress should now conceive that they have power to pass laws on this subject ? This Government depends upon the State Legislatures for existence. They have only to refuse to elect Senators in Congress and all is gone.” The Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions expressed his view entirely and he gave them his hearty support in North Carolina though the legislature contemptuously voted them under the table. But the Federalists were then in control.

When Macon became Speaker of the House of Representatives in Congress as a result of Jefferson’s elevation to the presidency, he had a better opportunity to make his principles in this respect felt. In the long and acrimonious controversy on the repeal of the Judiciary Act, he took an active part, not merely as Speaker, but as champion of the repeal on the floor of the House. His most characteristic speech was delivered on this occasion. In it he combated the Federalist position that repeal was unconstitutional; he also laid down a principle which was not new in the national legislature, but which was radical in the extreme, namely, that the state legislature could instruct with authority their Senators in Congress and recommend to their Representatives how they should vote on important questions. This would have been placing United States Senators substantially on the ground of ambassadors of their respective states, not unlike that of the representatives of the German states in the Imperial Bundesrath in Berlin. Macon’s friend Randolph, however, went a step further and declared that his state could also instruct Representatives. To meet this, James A. Bayard of Delaware replied that he was as much a representative of Virginia as was Randolph himself. This policy of the two most important southern leaders was not without influence throughout the south and west. It was the foundation-stone of the Jacksonian democracy in so far as it put the will of the sovereign people as expressed in the legislatures above all other authority. Macon also favored expansion and growth of the state courts to meet the increasing demands of the country. Although Macon was not an enemy to the Supreme Court, as were Jefferson and Randolph, he was in himself a standing protest against John Marshall’s great constructive decisions. He opposed the impeachment measures which ruined Randolph and taught Jefferson that there were limitations to the powers of a great popular majority.

It has been said that secession began with Jefferson in 1798, was accentuated by Randolph, and became a creed with the southern states after 1832 ; in other words, that Jefferson, John Randolph, and Calhoun were the apostles of this great dogma. This was in the main correct, but Macon was as important as Randolph in this development. He stood for the state as it was in 1789, and for a doctrine which was the legacy of the province, a legacy of intensely angry political struggles during the Revolution ; he stood, as he said, for a state which could at will withdraw its Senators from Congress, and which did receive representatives from foreign courts, accredited to its chief magistrates as late as 1793? Ten years before Randolph was heard of he was an advocate of the essential features of Randolph’s policy in the House of Representatives. It was the latter who became the political complement of the former, not the reverse. But Randolph’s strange personality and his telling stageacting first brought Macon’s doctrine prominently before the nation. These two men acquiring great influence and becoming, as it were, god-fathers to the younger generation of southern politicians, outlined thus the policy of nullification during the early years of Jefferson’s first administration. Can we be surprised then at Macon’s sending Jackson in 1833 an angry protest against the proclamation on nullification? He wrote Samuel P. Carson Feb. 9, 1833: “I have never believed a State could nullify and remain in the Union, but I have always believed that a State might secede when she pleased, provided she would pay her proportion of the public debt; and this right I have considered the best guard to public liberty and to public justice that could be desired. The proclamation contains principles as contrary to what was the Constitution as Nullification. It is the great error of the administration which, except that, has been satisfactory in a high degree. A government of opinion established by sovereign States for special purposes can not be maintained by force.”

One of the severest criticisms of Macon’s career, so far as students have criticised at all, has been that he constantly voted against all naval appropriations, even when war was imminent. The key to this part of his policy is to be found in his determination to prevent the least increase of power in the hands of the easterners. A navy, he thought, would be manned and controlled by Connecticut and Massachusetts, in other words, by the most capable seamen in the country. He was an agrarian who believed that the products of the plantation would find their way to European markets without our aid. It was immaterial to him whether Old or New England carried his tobacco to London. He would not have given a dollar to secure the carrying trade of the Atlantic.

The first speech he made in Congress on an important bill was in favor of a protective tariff for the encouragement of the infant cotton industry. This was in 1792. He prophesied that cottongrowing would become a source of great wealth to the United States. It is interesting to notice that this early attempt at protection to infant industries failed, because influential members of Congress thought cotton planting would destroy the fertility of the soil and ultimately impoverish the nation. Almost as many members from the south as from the north voted against the cotton protective tariff. But Macon, more alert than some have thought, was in closer touch with the interests of his state and he declared that the people there had “already gone largely in the cultivation of that plant.” Three years later, however, when Nicholas J. Roosevelt and Jacob Mark presented a petition to Congress asking for protection for an “ infant ” iron industry which they were promoting, he opposed it, notwithstanding his friend Gallatin favored the scheme. Macon said : “The best policy of all such cases is to leave that kind of business to the industry of our citizens ; they will work the mines if it is to their interest to do so.” It was the question here as to whose ox was to be helped out of the ditch.

At the extra session of Congress in 1797, when the bill providing for a large increase of the navy for the protection of commerce was pending, Macon was able to get an amendment passed which provided that the proposed frigates, when built and manned, should not be sent without the waters of the United States. This amendment was defeated in the Senate, but Macon and his friends were so persistent and powerful in their opposition that the plan was about to fail, and Samuel Sewall of Massachusetts declared: “ Gentlemen who depend upon agriculture for every thing need not put themselves to the expense of protecting the commerce of the country ; commerce is able to protect itself if they will only suffer it to do so. Let those States which live by commerce be separated from the Confederacy. Their collected industry and property are equal to their own protection and let other parts of the Confederacy take care of themselves.”

When Jefferson’s non-importation measure was brought before Congress in February 1806, Macon opposed all that part of it which recommended the building of war vessels and coast fortifications, but favored the proposition for gun boats : “I believe them better adapted,” said he, “to the defense of our harbors than any other. If we were now at war with any other nation, however gentlemen may be surprised at the declaration, I think we should do well to lend our navy to another nation also at war with that which we might be at war; for I think such a nation would manage it more to our advantage than ourselves.” A curious policy to be sure was this, but it was in accord with his general attitude toward naval armaments. The Southern agriculturalists had, from the beginning, opposed all such outlay, claiming that it was useless and believing, without saying as much however, that every ship built at the national expense to protect trade added to the power which was one day to grapple with their section in a fearful struggle for supremacy. In view of this final termination of the intense rivalry between the sections, Macon’s political foresight was not so poor as might at first appear. During the trying period of non-importation and embargo, he had his idea of agricultural supremacy clearly in view. He opposed every measure of the first Republican administration which seemed to obscure this issue.

In this policy Randolph joined him, though as much from motives of enmity to the President as from jealousy of New England. But Macon and Randolph were both staunch advocates of this so-called “mud-turtle” plan of Southern politicians. Randolph spoke out distinctly their view of things when he said in the debate on non-importation : “What is the question in dispute ? The carrying trade. What part of it ? The fair, the honest and useful trade that is engaged in carrying our own productions to foreign markets and bringing back their productions in exchange? No, Sir, it is that carrying trade which covers enemy’s property and carries the coffee, the sugar, and other West Indian products to the mother country. No, Sir, if this great agricultural nation is to be governed by Salem and Boston, New York and Philadelphia, Baltimore, Norfolk and Charleston, let gentlemen come out and say so. I, for one, will not mortgage my property and my liberty to carry on this trade.” When Randolph declared he would never vote a shilling for a navy and Macon said, “ lend your navy to a foreign enemy of our enemy,” they were opposing New England and speaking for their own section, for their own agrarian interests. Commerce and great cities had no more attractions for Macon than for Randolph or Jefferson.

In connection with this subject, Macon’s attitude toward slavery is to be considered. His view of the question may best be seen in his attitude to the prohibition of the importation of slaves into the United States. This measure came up in 1807. By the compromises on which the national Constitution is based, this traffic might be forever forbidden after January 1, 1808. But the economic conditions of the South had changed since 1787 ; and South Carolina, supported by the silent good-will of her sister states, now claimed that Congress could not constitutionally abolish the slave trade against the will and wish of a sovereign state. So much for the growth of the idea of state supremacy, a growth fostered by everlasting disputes between the South and the East, a growth dependent on the economic change just mentioned—cotton-growing based on plenteous slave labor. It was a question of dollars and cents, Macon thought, not of human freedom, which animated both sides in Congress. The prosperity of the South depended now on slavery, on agricultural development; that of the East on commerce which the Southern members so constantly decried and often crippled. The growth of the slave power was to the East what the advancement of commerce was to the South—success of a rival bent on controlling the Union in its own interest. The morality of the question was a secondary consideration ; though, as in a similar question of recent date, the speeches of the leaders were filled with moral and humanitarian professions. Macon said in committee of the whole : “I still consider this a commercial question. The laws of nations have nothing more to do with it than the laws of the Turks or the Hindoos. If this is not a commercial question, I would thank the gentlemen to show what part of the Constitution gives us any right to legislate on this subject.” Macon regretted sincerely the existence of the “dread institution,” yet he was as sincerely determined to maintain it as a right of the state and a check against the supremacy of the East. Both he and Randolph now maintained that a state could, if it desired, continue the slave trade independently of the Union, and they began to see that the equal growth of the South with the North depended on the expansion of the slave power. Here the second part of Macon’s life-long policy, agricul-turalism, became identical with the first, state sovereignty.

Macon did a great deal to put Jefferson in the presidential chair. North Carolina was the home of a strong Adams party, and it was with no little pains that the Republicans overcame the influence of the wealthy families enlisted under the banner of Federalism. Soon after the inauguration, Macon was given control of the federal patronage in his state ; this led to very cordial and confidential relations between the President and the Speaker of the House. And when Jefferson sounded Congress in 1802 with regard to his aggressive policy on the Mississippi, he received immediate assurance that he would be supported in any reasonable scheme he might set in motion for acquiring the control of lower Louisiana. The purchase of Louisiana, as all the world knows, was as much a piece of good luck as it was the result of Jefferson’s policy of expansion. When Macon heard of the favorable turn of things in Paris he wrote the President that “the acquisition of Louisiana has given general satisfaction, though the terms are not correctly known. But if it is within the compass of the present revenue, the purchase, when the terms are known, will be more admired than even now.” And then he adds what must have given his correspondent genuine satisfaction and which indicates Macon’s own political policy, “if the Floridas can be obtained on tolerable terms we shall have nothing to make us uneasy, unless it be the party madness of some of our dissatisfied citizens.” From this time on he never lost sight of the acquisition of Florida as one of the items of sound policy. There was much talk a little later about giving Louisiana to Spain in exchange for Florida, but Macon seems not to have given assent to any such plan. He was much interested in the acquisition of southern territory because he saw the significance of these possessions, first for the southern states and then for the Union. The balance of power between the two sections of the country was what he desired to see maintained even at that early stage.

January 1811, when the question of the admission of the new territory of Orleans was agitating the country, Macon expressed publicly his policy with regard to gaining southern territory; “much as the Southern country is desired and great is the convenience of possessing it”—were the terms he used. Not as territory, “not as a dependency,” but as independent southern states did he wish to hold that country. The same ideas prevailed with him in 1819 when Florida was annexed. But another question had the attention of Congress and the country—the organization and control of Missouri. In a letter to Bartlett Yancey, of North Carolina, touching this subject, he regrets very much the loss of “ Stone’s motion which would have given two degrees more to the people of the South.” With the failure, as Macon regarded it, of the South in the Missouri Compromise, his active participation in the expansion of the slave power closed. Randolph and Macon remained firm in their attitude toward this question and both voted against the Missouri Compromise. But the time had long since passed when Southern congressmen gave sincere attention to the counsels of Macon and Randolph; men were then filled with the ideas which Clay represented. It was not until 1832, when both were retired forever from active politics, that Southerners with Calhoun as their leader returned to what Macon always stood for, state supremacy, and only in 1837-1842 was it that their scheme of aggressive expansion became the creed of the great South Carolinian.

A paper on Macon would scarce be complete without considering his influence and power in pressing upon the nation the ideas he represented. In 1796 he became the undisputed leader of the Jefferson party in North Carolina; in 1799 the last attempt to defeat him was made. The same year he established in Raleigh the first and greatest partizan newspaper the state has ever had. Joseph Gales was its editor. Macon and Gales and their companions in politics waged a fierce and successful war of words in North Carolina in 1800. They carried the state for their party, but they could not prevent the election of four powerful Federalist congressmen in 1801. But these were defeated in 1803 through the industry and ability of Gales rather than of Macon. All parties recognized Macon’s right to leadership in his state from 1803 to 1828 ; and his authority was never questioned in his own party after 1803 except temporarily in 1808, when he opposed Madison’s candidacy, preferring Gallatin instead.

In national affairs his period of power was from 1801 to 1812. It began with his almost undisputed election to the speakership of the House. In the chair he was the equal of any who had occupied it; he used its almost despotic powers more often than any predecessor had done. He was without a Republican competitor in 1803 and with his faithful friend Randolph as chairman of the committee on ways and means, there was no defeating measures of which he approved. He was positive enough to make his wishes known by setting aside the precedent of the Speaker’s voting only in the case of a tie and having his vote registered as that of a member of the House. The present plan of presidential balloting, which required an amendment to the Constitution, was passed by his vote. Between 1803 and 1807 he allowed his friendship for Randolph and his dislike of Jefferson’s supposed leaning toward Madison to lead him astray. He favored openly the candidacy oi Monroe for President and opposed much of the non-importation plans of the administration; he even winked at Randolph’s foolish scheme of feigning sickness in 1806 in order, as chairman of the committee on ways and means, to defeat Jefferson’s foreign policy just referred to. This caused a breach between the President and the Speaker, a breach which resulted in the complete isolation of Macon. He was succeeded by Varnum in 1807. Jefferson commanded the Northern Republicans whom his conciliatory policy had called into prominence, and he still held enough of the Southerners to carry through all essential schemes. Randolph’s bizarre actions and wild speeches soon caused Macon to regret the political side of their David-and-Jonathan friendship, and before 1809 we find him voting in the main with the administration. At the opening of Congress in 1809 he was the choice of all Southern Republicans for Speaker and missed the election by only twenty votes. This returning popularity brought immediate recognition on the part of an administration floundering about in a slough of despondency. The way out of the bogs of embargo was being so earnestly sought after, that Macon, as a popular leader of the “old Republicans,” became one of the first characters of the country. Any bill he championed was likely to pass, but he did not bring one forward until after the Embargo Act had been repealed and a solution of all foreign difficulties was sought by Madison in 1810.

As a result of the very large vote for the speakership Macon was made chairman of the committee on foreign relations for the first session of the eleventh Congress. He at once introduced a series of resolutions looking to the settlement of our difficulties with the warring powers of Europe. The resolutions were debated somewhat at Vength and finally changed to the famous Macon Bill No. 1, which was undoubtedly an administration measure and which Gallatin had much to do with framing, but not all. After more than a month of debate the bill finally passed the House, January 27, 1820. Its main features were : (1) To exclude English and French war and merchant ships from American ports; (2) to restrict importations from England and France except such as came in American vessels; (3) to admit only such imports as should come direct from the country producing them. The bill also repealed the non-intercourse laws and limited the duration of the proposed act to March 4, 1810.

The purpose of Macon’s plan was to make England and France feel America’s power and to set the nation that refused to recognize our rights as neutrals clearly in the wrong before all sections of the country. But the Senate dominated by anti-Gallatin men defeated Macon’s bill in order to humiliate its reputed author. Macon Bill No. 2 was then introduced ; but with this Macon had nothing whatever to do, not even voting for it on its final passage, May 1. This bill promised free trade with either England or France in case either repealed its restrictive laws on neutral commerce. The nation which refused to change its policy was to be allowed no imports whatever into the United States. This plan was little more than a bid to France to come to America’s assistance and thus to isolate England completely, for no one expected the latter country to yield to our demands. The Macon bills occupied Congress throughout the session. Being the mouthpiece of the government, besides a most popular leader, Macon was practically the first character in Congress and among the first in the country.

With the beginning of the War of 1812 and the appearance in Congress of Calhoun, Clay, Lowndes, Cheves—the younger generation of politicians—Macon’s influence in national affairs came practically to an end. He remained easily first in North Carolina, however, as long as he lived.

Macon’s place and influence in Southern history is alongside that of John Randolph; he was before Randolph in his advocacy of state supremacy and more influential at all times because more practical and reasonable; he was a Southern agrarian of the Jeffersonian type and in this he was in full accord with Randolph; his policy of southern expansion was a dim outlining of Calhoun’s aggressive plan of 1842 ; and this attitude of his compelled him to espouse the cause of slavery since slavery was the basis of Southern wealth, and necessary as a weapon with which to fight the free states. His influence was based on the control of his own state and on the confidence which his unimpeachable sincerity and honesty inspired.

This essay was originally published in the American Historical Review, Vol 7, No. 4, July 1902.