Many today feel that true Southerners living in the eleven States of the former Confederacy are, in many ways, once again fighting for their very existence and face the dismal prospect of the South they once knew becoming, as in Margaret Mitchel’s classic novel, a dream that will all too soon be gone with the wind. Virtually everything they now hold dear in regard to what constitutes their vision of Dixie seems to be under siege. Sadly, however, the enemy is not merely at the gates of the South, but like the Yankee invaders of 1861, they are already within its walls. Unlike Lincoln’s legions of over a century ago who came to destroy the South with the sword, this new invading army, one that began its entry into the South a few decades after the War Between the States, came initially with far more benign intentions. Only in recent years did the mad desire to tear down all Southern heritage and tradition again rear its ugly head.

During the latter part of the Nineteenth Century, the impoverished South had little else beyond its pride, faith and grit. The South’s will to rise up once again was certainly there in men like Georgia’s Henry Grady, the editor of the “Atlanta Constitution,” who had a broad vision of a new, industrialized South. Sadly, however, the South lacked the much needed wherewithal to accomplish that goal. Such means were to be provided in large part by various types of capital investment supplied from sources north of the Mason-Dixon Line.

From the 1890s to the early years of the Twentieth Century, the South’s first major step toward large-scale industrialization was the rebuilding and expansion of its railway system, much of it with Northern financing. During that period, railroad construction increased over four hundred percent and with it ultimately came the later growth of a new age of manufacturing, again largely developed with non-Southern funding. The initial industries were textile facilities that used Southern cotton and labor but were mainly subsidiaries of Northern mills. Later, an iron and steel industry fueled by Southern coal was also developed in much the same manner.

The defeat of the Confederacy and the end of slavery also brought the demise of the plantation society which had produced the cotton that would be needed to feed the burgeoning new textile industry. For a while, raw cotton was in short supply and prices soared. This condition was only stabilized when small farmers began to abandon the raising of food crops in favor of the far more lucrative white gold. A side effect of this was that it forced many in the agrarian South to rely more on commercially produced foodstuff and other goods, giving rise to a new mercantile culture which, combined with the new industrialization, created an expansion of urban living.

Aside from manufacturing, other forms of outside investment also had a great impact on the area. In the early 1920s, New York industrialist Henry Flagler, the founder of Standard Oil Company, began a massive development of Florida’s southeast coast, particularly in what is now Miami and Palm Beach, as well as financing the Florida East Coast Railway to bring people to that area. Flagler and other Northern developers not only brought new wealth to Florida, but an entirely new population that eventually spread to many other sections of the South.

All of this was reflected in the census figures from 1890 to 1920. During that period, the average national population growth rate was fifty-seven percent and in the South only Mississippi, Tennessee and Virginia fell well below that average, with Florida and Texas much above it at rates of one hundred five percent and eighty-two percent respectively. Due to the land boom in Florida during the following decade, that State’s growth rate rose an additional fifty-two percent which placed Florida’s one hundred fifty-sen percent total growth rate from 1890 to 1930 at more than double the national average of seventy-three per cent for that period.

Following World War Two, there was a second industrial revolution in the South, with even more massive investment by both Northern and West Coast firms seeking a non-union workforce backed by right-to-work laws, lower taxes, an expanding transportation network and a better climate. Thirty years later, foreign investors from Europe and Japan also turned their sights on the South and constructed many large production facilities throughout the area. All of this had an even more profound effect on the region’s demographics.

Prior to 1900, over ninety-five percent of those living in the eleven former Confederate States were Southerners by birth but within two decades, the new invasion began with an influx of migrants from the North. By 1920, almost twenty percent of those living in Florida were born outside the South. In Virginia, the number rose to about ten percent and three to five percent in Texas, Georgia, the Carolinas, Tennessee and Arkansas. Only in Alabama, Louisiana and Mississippi did it take another thirty years to see those number begin to rise appreciably.

In more recent years, besides the ever-growing number of people moving South from other States, there has also been a surge in immigration from other counties. A survey made a few years ago revealed that more than half of Florida’s residents were not born in the South, with thirty-two percent of that State’s population coming from non-Southern States and twenty-three percent being foreign-born. Virginia and North Carolina had the next highest numbers, with twenty-seven and twenty-one percent respectively coming from States outside the South and thirteen and nine percent from other countries. The population percentages for the remaining eight former Confederate States were as follows:

| State Non-Southern % Foreign % Total % |

| Texas: 14 17 31 |

| Georgia: 18 11 29 |

| South Carolina: 19 6 24 |

| Arkansas: 16 5 21 |

| Tennessee: 14 5 19 |

| Alabama: 10 4 14 |

| Louisiana: 7 4 11 |

| Mississippi: 8 1 9 |

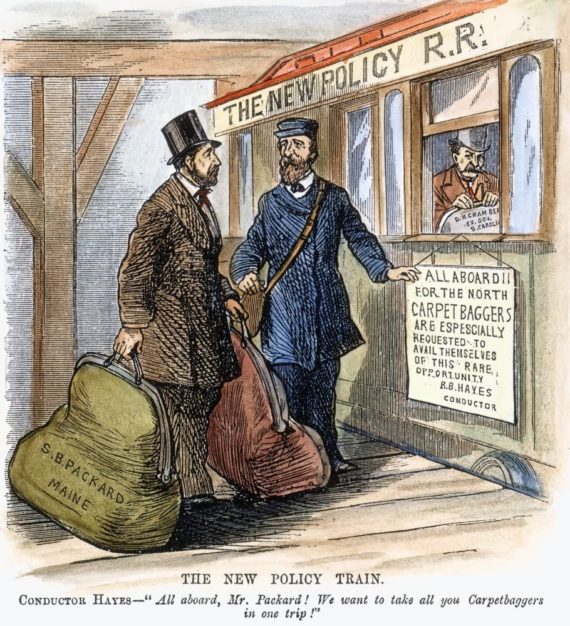

This shift in demographics brought with it important social changes as well. The new arrivals carried with them not only a different culture but their own views on American history and varying reactions to many forms of what had always been considered as normal facets of Southern life. The latter was particularly true in relation to the civil rights movement in the 1950s and ‘60s. Moreover, many of the South’s new residents entered the world of Southern academia, both as instructors and students, and began to introduce the Northern versions of the antebellum South, secession, the War between the States, the Reconstruction Era and, of course, slavery and what they thought constituted racism and “white supremacy.” Through this, the Northern mantra that secession was treason and the South was only fighting to defend slavery, while the North’s invasion was only to quell a rebellion and free the slaves, became firmly imbedded in the South’s textbooks.

These changes also had a profound effect on Southern politics. When the enforced Republican Reconstruction Era finally ended and the South was once again allowed to elect its own leaders, the area swiftly returned the Democratic Party to power. This one-party rule lasted for almost a century and was only shattered in 1964 when Conservative Republican Barry Goldwater carried the States of Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi and South Carolina. After that, a number of prominent Southern politicians, such as Senator Strom Thurmond of South Carolina who had headed the State’s Rights Party in the 1948 presidential race, crossed the aisle to join the Republican ranks. Likewise, many conservative Republicans from outside the South, like Newt Gingrich of Pennsylvania, traveled South and were elected as members of Southern congressional delegations.

The aftermath of these changes can be clearly seen in the makeup of the current Congress. While seventeen of the twenty-two United States senators from the eleven former Confederate States are still Southerners by birth, one glaring exception is Virginia, the State in which the capital of the Confederacy was located and was the scene for many of the South’s major battles. There, both senators are from non-Southern States.

The situation in the House of Representatives, however, is far different, with almost a third of the hundred thirty-seven congressmen from the eleven States of the former Confederacy being born in either a non-Southern State or a foreign country. Again, Virginia is the worst example, where only one of its eleven congressmen was actually born in the South. Eight others in that State were born outside the South and two in foreign nations. Florida today runs a close second to Virginia though, with twelve Southern-born congressmen, thirteen from non-Southern States and two from foreign countries. Only three of the States in question, Arkansas, Louisiana and South Carolina, have all-Southern congressional delegations.

During the early days of this new invasion, there had existed in America a general live-and-let-live attitude in regard to the South’s past. In the last forty years, however, there has been a growing intensity of enmity in the nation concerning all things related to the Old South, its history, its heritage and its culture, with much of the animus being shared by the non-native Southerners now living in the South. This virulent anti-Confederate and anti-Southern sentiment has led to the current movement to eradicate entirely all the South’s banners, heroes and monuments. A number of these acts were even instituted, or at least sanctioned, by some of the new leaders of the Southern States . . . and there is no end in sight as to how much further the erasure of Southern history and heritage will proceed before every vestige of what we hold dear about the South is completely gone or altered beyond recognition.

What path the South must take to address this situation is a daunting challenge, but one that must be taken up if the South we know and love is to survive. First on the agenda is in the field of education, specifically the introduction of far more balanced courses in American history. To accomplish this, concerned citizens must first become far more active in school affairs, from greater participation in parent-teacher activities to running for seats on local boards of education. The public must also get behind all movements to wrest control over educational matters from the hands of the Federal government and return such powers to the States. The latter is a much more complex problem, however, and one that involves an entirely new approach to the present political structure.

While birds need two wings to fly, political parties certainly do not. For almost a century, both major parties in America have attempted to function with opposing conservative and liberal factions. As the years passed, these wings have spread further apart . . . which has led to endless battles both within the party organizations and in the costly, bitter and divisive primary elections which have left lasting scars on each party. To add further chaos to the problems of primary elections, twenty-two states, including nine of the former Confederate States, have now seen fit to adopt the virtually suicidal practice of “open primaries” in which non-registered and/or cross-over voters are allowed to select party candidates. The obvious answer, of course, would be a total realignment of the major political parties into ones which solidly represent conservative and so-called progressive approaches to government . . . with the electorate given the choice to decide which path the nation should follow. If it should be the conservative approach, only then could the constitutional right of the States to govern their own affairs in such matters as education be restored. These will not be easy roads to follow, but the first steps toward such ends must soon be taken if there is to be any hope of not only preserving what still exists of Southern values and culture, but also attempting to reeducate its non-Southern population and the rest of the nation concerning Dixie’s true heritage and history