During the past half century, there has been an ever-increasing tide of derogatory comments about the South in general and the Confederacy in particular. In more recent years, what began merely as verbal sneers and written slurs have now evolved into far more sinister acts of actual violence being perpetrated on our memorials and monuments. Even worse, there is now a growing body of both Federal and State legislation that calls for the total erasure of an entire culture and history. While the majority of this mendacity initially emanated from the Northeast and West Coast, all too much of it has now either originated or is being disseminated by an active “fifth column” of elected officials, academics and the media within the South itself.

An excellent exemplification of this would be a column written a couple of years ago by Jeff South, an associate professor of journalism at Virginia Commonwealth University. In his piece, the Texas-bred author cited another article he had written forty years earlier for a Virginia newspaper about the thirty thousand-strong 1981 Boy Scout Jamboree held at Fort A. P. Hill near Bowling Green. While the original story merely related the facts about the theme of the event, “Scouting’s Reunion with History,” South now regrets that he did not tell the Scouts that their reunion was being held at a facility which honored “a man who fought to maintain slavery.” Perhaps the fact that South has also attended and taught at three universities in communist China might have had some bearing on his current thoughts regarding the rewriting of history, specifically renaming all the various United States military facilities which honor Confederate heroes.

According to Professor South’s current narrative, the Army installations that were established in the South during both World Wars were named after Confederate leaders merely as a means to recruit more Southern white men into service. He also stated in his recent article that the two wartime eras were still a time when the Southern States were promoting the “Lost Cause ideology” and that the Army officials, acting in a spirit of reconciliation, were willing to view the Confederate generals as tragic heroes rather than what South now terms “treasonable racists.” The actual naming of United States military facilities is quite a different story however. The initial policy for this appeared in a War Department general order of 1832 which merely stated that all new posts will be named by the War Department. In 1878, a new War Department order allowed the regional commanders to choose the names which resulted in military bases being given a wide variety of names, including those of cities, geographical sites, non-military individuals and even Indian tribes.

The naming of Army facilities after military leaders did not come about until Quartermaster General Richard Batchelder proposed the idea in 1893. The plan that was adopted was to have the Secretary of War name the facilities after consulting with the base commanders, the chief of the War College’s Historical Section and civilian officials in the areas involved. Two decades later, this resulted in a number of installations in the South being named after Confederate generals. Even after the practice became official U. S. government policy in 1939, more bases were named for such military leaders.

While various alterations in the naming process were made over the years, including the creation of a Memorialization Board in 1946 by then General of the Army Eisenhower which set forth certain criteria for naming, no radical changes were introduced until last year when the Defense Department and Congress tried to create a commission under the National Defense Authorization Act to rename bases that honored what they termed “traitors who fought to preserve slavery.” President Trump vetoed the measure and called it a “politically motivated attempt to wash away history,” but his veto was overridden by both houses of Congress and an axe-wielding group with the elephantine epithet of “The Commission on the Naming of Items of the Department of Defense that Commemorate the Confederate States of America or Any Person Who Served Voluntarily with the Confederate States of America” became an Orwellian reality charged with erasing all “names, symbols, displays, monuments and paraphernalia” related to such DOD “items.”

The four DOD members who make up this modern day version of the French Revolution’s Committee on Public Safety are Admiral Michelle Howard, who was the first African-American woman to command a Navy ship; Marine General Robert Neller, who was born at Camp Polk in Louisiana and graduated from the University of Virginia; Ms. Kori Schake, the Director of Foreign and Defense Policy at the American Enterprise Institute and a writer for the left-leaning magazine “The Atlantic”; and finally retired Army Brigadier General Ty Seidule, whose highly opinionated book “Robert E. Lee and Me” was so eloquently harpooned recently by Abbeville Institute’s Philip Leigh. The delegation from Congress that will also be part of the Commission includes retired Army Lieutenant General Thomas Bostick, the first African-American to command the Army Corps of Engineers. Lonnie Bunch, the former director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African-American History and Culture, had also been named but said he could not serve for “personal reasons.”

The Commission’s first targets in the South will be ten installations named after Confederate generals, as well as Fort Belvoir in Virginia. The latter is a World War One training center in Fairfax County that was originally named Camp A. A. Humphreys after Union Major General Andrew Humphreys. In the 1930s, Representative Howard Smith of Virginia requested that the facility be renamed for the historic Belvoir plantation that had once stood on the site. Much of the Fairfax family’s plantation had been burned by the British at the end of the Revolutionary War in 1783 and was completely destroyed by them in the War of 1812. Since 1973, the site has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places. In the thinking of the new Commission, Fort Belvoir’s “crime” is that the former plantation had used slave labor, despite the obvious fact that it had ceased to exist at a time when slavery was still a common practice throughout most of America.

Five of the other bases on the Commission’s primary hit list that were created prior to or during World War One are Camp Beauregard in Louisiana that is now a National Guard facility; Fort Benning in Georgia; Fort Bragg in North Carolina and two in Virginia, Fort Lee and Camp Pendleton. The latter, named for Brigadier General William Pendleton, the chief of General Lee’s artillery, is also now a National Guard base. The remaining five that were created to train troops in World War Two are Forts A. P. Hill and Pickett in Virginia; two in Texas, Fort Hood and Camp Maxey which is now a National Guard facility; Fort Polk in Louisiana and Fort Rucker in Alabama.

There are five additional former Army installations that were named in honor of Confederate generals, and three of these also face some sort of possible name change. The oldest is Camp Pike in Arkansas which was named for Brigadier General Albert Pike, the Massachusetts man who led Indian troops in Oklahoma and Arkansas. While the camp was deactivated after World War One, the Arkansas National Guard Museum retains the name . . . thus being a potential target. The same holds true for the deactivated Camps Van Dorn in Mississippi and Breckinridge in Kentucky that are now both U. S. Army museums. The last two facilities, Camp Forrest In Tennessee and Camp Wheeler in Georgia are no longer in existence. The one named for the “Wizard of the Saddle” was a large World War Two training center and prisoner-of-war camp that was decommissioned and torn down in 1946. Five years later, the site became the Air Force’s Arnold Engineering Development Center, named in memory of Air Force General “Hap” Arnold. The second former facility is Camp Wheeler that was built in World War One and used again in World War Two. This camp was also decomissioned and demolished in 1946, but there the land was returned to its original owners and all that remains is a historical marker. Of course it is very possible that, like so many other such markers, General Wheeler’s will also be “contextualized.”

The removal of these names will, as President Trump said, “wash away history,” a history that has long been an integral and vital part of America’s past. In the case of General Lee, the man who was offered command of the Union Army in 1861, many in America, in both the North and South, wholeheartedly agree with former President Eisenhower that Lee was one of the four greatest figures in the nation’s history. This sort of praise has also been echoed by many others around the world who have any sense of our country’s true history.

To illustrate Lee’s national importance, his image has appeared on five U. S. postage stamps . . . more than for most U. S. presidents. The first was in 1937 when President Franklin Roosevelt ordered that both Lee and “Stonewall” Jackson be depicted on a commemorative stamp to be issued along with another showing Generals Grant and Sheridan. Two years later, Lee shared a second commemorative stamp with George Washington and in 1970, he was pictured with both General Jackson and President Davis on a Stone Mountain memorial issue. Lee’s image alone was used on a stamp in 1955 and another as late as 1995. He and Jackson were also the subjects of an official U. S. commemorative half dollar that was minted in 1925 to raise additional funds for the Confederate monument on Stone Mountain in Georgia.

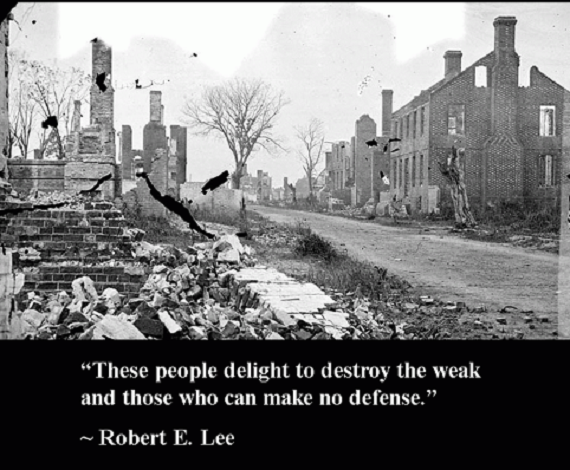

Certainly the time has come to end this utter folly and return to some sense of historical reality, rather than the current never-never land of what should have been, and now must be. While there is little the South can do to alter or even influence the anti-Confederate and anti-Southern mindset that exists outside the South, we can at least try to appeal to those below the Mason-Dixon Line who foolishly follow the same path. We must reach out to any politician, academic or media personality who espouses such sentiments and let them know, as General Lee once said, that “these people” are destroying the weak and those who can make no defense.

Two good targets with which to start would be the pair of Southerners who are now part of the name-removal cabal in Congress: Representative Mike Rogers, an Alabama Republican who is the ranking member of the House Armed Services Committee, and the congressman he appointed to the new renaming Commission, Representative Austin Scott, a Georgia Republican.