After the end of the War Between the States, the Union army established the District of Texas under the command of Major General Gordon Granger. The Emancipation Proclamation had been enforced by the Union army in every other state of the Confederate States of America which it had occupied. Texas escaped Union occupation during the war and the Union army did not occupy the state or any part of it until after the war’s end. General Granger issued General Order No. 3, which he read publicly in Galveston on June 19, 1865. It stated that all slaves in the state of Texas were free in accordance with the Emancipation Proclamation, which had been issued by President Abraham Lincoln two and a half years earlier. The day, which has been since dubbed Juneteenth, has since come to commemorate the abolition of slavery in Texas. When I lived in Texas in the 1950’s, it was celebrated as such by many of the state’s black citizens. It became an official state holiday in 1979. However, after I moved to Virginia, I never heard of its celebration again until recent years. Now, it is recognized in other states and there is a proposal that it be made a national holiday. But what significance does it have beyond Texas?

Lincoln issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, 1862. One month earlier, he stated in a letter to Horace Greely dated August 22, 1862:

“If there be those who would not save the Union, unless they could at the same time save slavery, I do not agree with them. If there be those who would not save the Union unless they could at the same time destroy slavery, I do not agree with them. My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that. What I do about slavery, and the colored race, I do because I believe it helps to save the Union; and what I forbear, I forbear because I do not believe it would help to save the Union.”

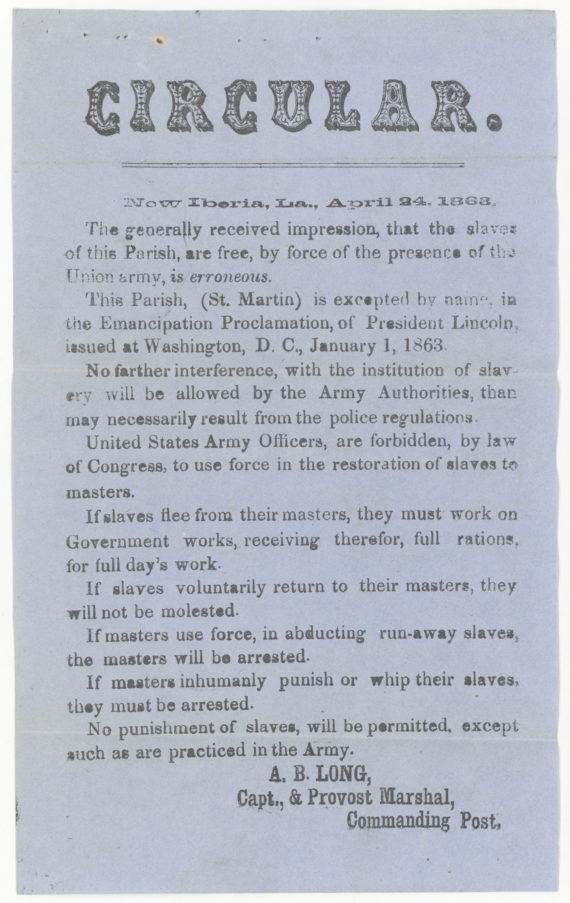

Lincoln had already drafted the preliminary Proclamation before he wrote this. The final Proclamation was issued on January 1, 1863. It declared freedom to the slaves in ten Confederate states: Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas, Louisiana, and Texas. However, it exempted in Virginia “the forty-eight counties designated as west Virginia, and also the counties of Berkley, Accomac, Northampton, Elizabeth City, York, Princess Ann, and Norfolk, including the cities of Norfolk and Portsmouth.” It also exempted in Louisiana “the Parishes of St. Bernard, Plaquemines, Jefferson, St. John, St. Charles, St. James Ascension, Terrebonne, Lafourche, St. Mary, St. Martin, and Orleans, including the City of New Orleans.” These areas were all under Union control. A circular issued by Union Provost Marshall Captain A.B. Long in New Liberia, Louisiana on April 24, 1863, informed the slaves in St. Martin Parish who thought that they were freed by the Emancipation Proclamation that they were not because that Parish was exempted in it. Furthermore, in addition to West Virginia, the Proclamation left slavery intact in six other states: New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Missouri. All of these states were completely under Union control except for Tennessee, which was mostly under Union control except for East Tennessee, which was of predominantly Union sympathy. Philip Leigh has written more at length about the Emancipation Proclamation than can be covered in this article.

The slaves in the District of Columbia had been freed by act of Congress on April 16, 1862, and those in U.S. territories by the same on June 17, 1862, before the Emancipation Proclamation was issued. Lincoln then tried to get Delaware to be the next entity to free its slaves, but the state refused. The District of Columbia and the territories were the only jurisdictions over which the Federal Government has this authority. Furthermore, the Constitution gives Congress the power to enact laws, not the President, and Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution gives no power over slavery to Congress. Under the Tenth Amendment, authority over slavery in the states was reserved to the states themselves. Therefore, the Emancipation Proclamation did not legally free a single slave.

Four states emancipated their slaves by state action after the Emancipation Proclamation was issued. They were Maryland on November 1, 1864, Missouri on January 11, 1865, West Virginia on February 3, 1865, and Tennessee on February 22, 1865. Even if you still think that the Emancipation Proclamation freed the slaves in the ten states in which it declared them free, not only were the slaves in the exempted portions of Virginia and Louisiana not yet free by this time, neither were those in New Jersey, Delaware, or Kentucky. In fact, New Jersey, Delaware, and Kentucky all rejected ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment and their slaves were not freed until it was ratified on December 6, 1865. The only other slave state which rejected the Thirteenth Amendment was Mississippi, which was also the only former Confederate state to do so. Every other slave state ratified it.

The current push to recognize Juneteenth is based on the allegation of its advocates that it brought freedom to the last slaves and, therefore, marked the end of slavery in the United States. However, it is obvious from the historical facts that this is not true. This push points to slavery in the former Confederate states while turning a blind eye to the fact that slavery still existed in three other states for almost six months after Juneteenth. Not only that, but two of those three states, New Jersey and Delaware, were Northern states. Only Kentucky, which was a Border State of the Upper South, was not. There were slave sales going on in Kentucky all the way through November 1865 and they were advertised in the state’s newspapers.

Maps in history books depicting the free and slave states always depict the Mason-Dixon Line as the dividing point. However, Dr. James J. Gigantino II showed this to be untrue in 2015 with the publication of his book The Ragged Road to Abolition: Slavery and Freedom in New Jersey, 1775-1865 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press). When the United States became a nation in 1776, all thirteen states had slavery. Slavery was eventually abolished in all of the New England states and in the Mid-Atlantic states of New York and Pennsylvania. However, this did not happen in the other two Mid-Atlantic states, New Jersey and Delaware. New Jersey passed a law for gradual abolition of slavery in 1804, but gradual emancipation in the state was so dragged out that the last slaves in the state were not freed until the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865. The boundary between free New York and slave New Jersey was the actual northern most dividing point between the free and slave states, not the Mason-Dixon Line. In his book, Dr. Gigantino wrote of the interaction of New Jersey slaves with others in that region, stating:

“The Catherine Market in New York City likewise saw significant interactions between enslaved New Jersey blacks and free New Yorkers on an almost daily basis. Many slaves sold their wares alongside their masters’ and established social and business contacts with whites and free blacks. These social relationships frequently manifested themselves in dance competitions after the market closed. One pitted Ned, the slave of Martin Ryerson of Tappan, against free blacks from across the region.” (p. 126)

Delaware never passed a law abolishing slavery. Furthermore, while both New Jersey and Delaware remained slave states throughout the entire war, every regiment raised from both states fought in the Union army. There was not a single Confederate regiment from either state.

Virginia has now made Juneteenth a state holiday, but the slaves in the southeastern counties of that state which were excluded from the Emancipation Proclamation were not freed until almost six months later, when the Thirteenth Amendment was ratified. That date, December 6, 1865, was the date on which the last slaves were truly freed. Therefore, December 6 should be celebrated as Emancipation Day. But, then, that would not promote the Marxist/politically correct/woke agenda, which includes advocating for Confederaphobic hysteria and which is what the push to make Juneteenth a national holiday and a holiday in states other than Texas is really all about. And that agenda does not care anything about the facts.