In the early 1870s, a young pre-law student at Howard College was inspired by classmate and future wife, Mamie Friend. James Alan Bland would listen to the homesick sentiments of Mamie and her home in tidewater Virginia. During a trip to meet Ms. Friend’s family the two sat down together with pen, paper, and a banjo. Bland composed his song to illustrate the reflections of a freed slave, who in old age, embraced memories of a former life on a plantation. The apologue conjures up memories of a simple agricultural life, the beauty of the natural world of tidewater Virginia, and a strong affection towards a former master. According to the “Psychology of Music,” Bland uses the key of A to declare innocence, love, cheerfulness, and acceptance of one’s affairs. C minor reinforces key of A with a languishing sigh of a home sick soul. The G major invokes calmness, rustic scenery, faithfulness, and friendship. Using the lens of modern scholarship, it is easy to find flaws of Mr. Bland’s ode. The lines below are difficult, illogical, and subservient to the modern ear.

“There’s where the old darke’ys heart am long’d to go,

There’s where I labored so hard for old massa,

There’s where this old darke’ys life will pass away.

Massa and missis have long gone before me,”

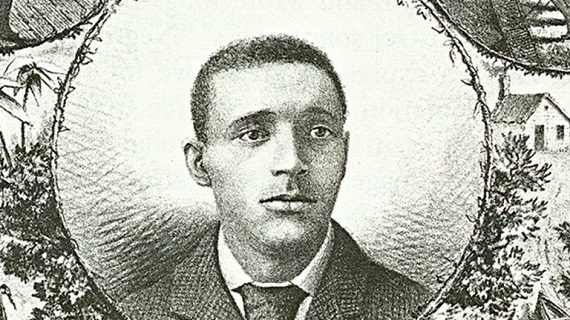

In order to understand “Carry Me Back to Old Virginny”, the reader must come to know James A. Bland. He was born on October 22nd, 1854 in Flushing, New York, to a free and educated African American family. James’s father was the first African American to graduate from Oberlin College in 1845. The family relocated to Washington, D.C., in the late 1860s where the head of the family worked as an examiner in the U.S. Patent Office. James and his father enrolled together at the Howard College. Father studied law and son studied liberal arts as a pre law major.

The true passion of James Bland was the banjo. He was self-taught at the start with a homemade banjo constructed of scraps wood and wire. Bland’s father purchased an eight-dollar banjo for his son and by age 14 he was performing in front of audiences. Bland’s early banjo compositions were inspired by spirituals and folk songs that were commonly heard on the campus of Howard College. Upon graduation in 1873, Bland began performing at the Manhattan Club, saloons, and was a U.S. House of Representatives page.

Bland’s ambitions to be a stage performer were met with rejection when he applied to join all white minstrel shows. His break came in 1875, when Bland accepted a role in Billy Kersand’s all-negro minstrel troupe. By 1881, James had joined the Callender and Haverly’s Georgia Minstrels Show, which launched a tour of Europe. Black minstrel performers mirrored white minstrel performers by blackening their faces, using white eye outlines, exaggerated red lips, stereotypical dialogue, and comical dances.

It was during this period that Bland composed somewhere between six hundred and seven hundred songs. Fifty-three of those songs were copyrighted and published. “Carry Me Back to Old Virginny” is likely an adaptation of Edward Christy’s early version from the 1840s. The lyrics are decidedly different for the song centers on the life of an oysterman on tidal waters of Virginia. The Christy version of the song was well known and popular during the Civil War. It would have been played with a banjo, accompanied with fiddle and bones.

Bland’s compositions were known across America, class divisions, racial divides, and in Europe. The success of the songs catapulted the Georgia Minstrels into a top act that earned as much as $10,000 a year for Bland. By the early twentieth century, Bland’s music was recorded in shellac for the millions of Victrola players housed in American parlors. White and black recording artists entertained old and new generations of Americans with Bland’s timeless folk music. “In the Evening by the Moonlight” (1880), “Oh, Dem Golden Slippers” (1879), and “Hand Me Down My Walking Cane” (1880) are minstrel folk songs that were imprinted into the fabric of American popular culture.

Back in 1914, Romanian-born opera star, Alma Gluck, recorded “Carry Me Back to Old Virginia” for the Victor Talking Machine Company. The recording was smash success selling one million copies earning a gold disc. Only six other records up to that time had ever reached the seven-figure mark. From this moment on the song became known to Americans yet again and its popularity would endure into the 1960s.

Many popular music artists of multiple genres recorded “Carry Me Back to Old Virginny.” Most of the time the lyrics were altered to drop the negative racial tones. Marian Anderson, the famed contralto and civil rights pioneer, recorded the song in 1941. I like the Jerry Lee Lewis version cut in 1965 at the Sun Studios in Memphis, Tennessee. Even Elvis included the state song in his repertoire. The most soul stirring version is by Ray Charles in 1964. I can remember that the Marching Virginians would always perform an instrumental version of the song at football games. In modern times, blue grass band The Old Medicine Crow Show, adapted the song to illustrate the perspective of a young soldier in the Civil War.

After a command performance for Queen Victoria and Prince of Wales in 1881, the Georgia Minstrels returned to tour the United States. Bland chose to remain behind and for the next twenty years he lived in London where he continued to compose, perform, and thrive. In 1901, Mr. Bland returned to the United States to find a very different world. Minstrel shows had gone into decline and were replaced by vaudeville. It became difficult to continue his passion. “The Sporting Girl” was his last published composition, earning him $250. He did manage to find work in a law office in Philadelphia.

On May 5th, 1911, James Alan Bland died alone from tuberculosis and was buried in an unmarked grave in Merion, Pennsylvania. In 1939, The American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers (ASCAP) located Bland’s grave and erected a headstone. The Virginia Lions Club added to the gravesite with a monument to Bland. Since 1948, the Virginia Lions Club awards scholarships to young Virginians in Bland’s memory. Contestants must submit and perform a musical composition.

“Carry Me Back to Old Virginia” was adopted as the official state song in 1940. The bill was signed into law by Governor James H. Price. Beginning in 1970 a long campaign to retire the venerable and controversial state song was underway. Newly elected state Senator Doug Wilder, the first African American to hold this position in one hundred years, introduced a bill to end the tenure of the “Carry Me Back to Old Virginia.” In his first speech, Wilder declared that the lyrics were offensive and glorified slavery. The bill failed and the vote divided both Democrats and Republicans. The battle of the state song continued along these lines throughout the 1970s and 1980s. Efforts were made to at least change the offensive lyrics, but consensus on what to replace them with could never be reached. When Wilder was elected to the position of the first black Lt. Governor in 1985 and as the first black governor in 1990, he continued his quest to remove the state song. Barriers, a lack of consensus, and legislative road blocks prevented this from happening.

In the mid 1990s, Republicans changed course with the state song debate. Instead of altering, eliminating, or replacing the song, Republicans wanted to retire the tune to the honorable level of “state song emeritus.” Something had to be done. The debate had gone on for a quarter of a century. Retirement might not win over black voters, but it would appeal to moderate white voters. In January of 1997, Senate Bill 801 was reported out of committee and managed to pass the General Assembly. Governor George Allen signed the bill, declaring “Carry Me Back to Old Virginia” state song emeritus. A state committee was formed and a contest was initiated to select a replacement. Over 260 entries were given to the committee. Even sausage maker and country crooner Jimmy Dean made a pitch No agreement could be reached on a proper replacement. In 2006, there was an attempt to adopt “Oh Shenandoah” as a temporary state song for the upcoming quadricentennial of the founding of Jamestown. The idea never made it out of committee. And ever since then, dear ole Virginia has been without a state song.

“Carry Me Back to Old Virginia” could not endure the 21st century, and it was a judicious move to break the deadlock with an honorable retirement. The song still lingers. Its lyrics and notes still echo even now. The merits and condemnations of Bland’s composition will be debated over and over by scholars, historians, and audiophiles. It remains a conflicted paradox of memories, themes, emotions, and stage. The inner conflict should not have coexisted with culture and society. Yet it did and for a very long time too. That is the very essence of what draws Americans to study Southern culture and history.

I find myself drawn to the story of James A. Bland. It is remarkable how a man, who did not know Virginia, came to capture so much about Virginians in a few simple stanzas. Here was a man destined to be forgotten, but his powerful notes and verse brought his memory back to the forefront. In 1970, Bland was posthumously inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame. Scholar, mathematician, and sociologist Kelly Miller, who taught Bland at Howard, had this to say about the immortal composer:

“He holds up a mirror to nature. James A. Bland constitutes a unique character in lyric literature, in that, though being a scion of an enslaved race, he immortalizes the soul yearnings of his people to glorify the land where his ancestors were held in bondage.”

In my view, “Carry Me Back to Old Virginia” is a mirror of who Virginians once were.