Are pronest to it, and impute themselves…

Tennyson, from Idylls of the King (1)

The US Supreme Court, in Texas vs. White, ruled that secession from the Union was unconstitutional. Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase, in 1869, wrote the majority “opinion of the court.” His opinion was not that of Thomas Jefferson, the author of the Declaration of Independence, in which he had written:

Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes… But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object, evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security… (2)

Nor was it the opinion of the Virginia Convention that ratified the Constitution, in stating the condition upon which Virginia was joining the Union:

We the Delegates of the People of Virginia … Do in the name and in behalf of the People of Virginia declare and make known that the powers granted under the Constitution being derived from the People of the United States may be resumed by them whensoever the same shall be perverted to their injury or oppression… (3)

Nor was it the opinion of the New York Convention that ratified the Constitution, in stating the condition upon which New York was joining the Union:

We the Delegates of the People of the State of New York … Do declare and make known … That all Power is originally vested in and consequently derived from the People, and that Government is instituted by them for their common Interest Protection and Security… That the Powers of Government may be reassumed by the People, whensoever it shall become necessary… (4)

Nor was it the opinion of the New England States in their Hartford Convention in 1814, when they threatened secession over the War of 1812. Nor was it the opinion of the Northern States that, at one time or another, threatened secession over the Fugitive Slave Law, the Mexican War, and the admission of Texas. Nor was it the opinion of the Radical Abolitionists who loudly clamored for “No Union with slaveholders!” (5) Nor was it the opinion of the States of the Southern Confederacy that did in fact secede. Nor was it the opinion of the many Northern newspaper editors who were thrown into prison for expressing it, and who had their presses destroyed when Lincoln unconstitutionally suspended the writ of habeas corpus while waging his unconstitutional war (all in violation of Art. I, sec. 8 and 9; Article III, section 3; and the First Amendment to the Constitution, although all have since been cleverly obfuscated by the Lincoln sycophants and “Court Historians”). (6)

While there were those of the Hamilton-Clay-Webster persuasion who wanted a stronger centralized government, the Jeffersonian States’ Rights view of the Constitution prevailed until 1865. Before the war, the Constitution limited the powers of the General Government and guaranteed the reserved powers to the States, but Lincoln’s War and the Radical Reconstruction that followed was a revolution, a bloody and murderous usurpation of arbitrary power that transformed the voluntary Union of sovereign States created by the Founders, into a coerced Empire pinned together by bayonets. Before the war, the General Government was made to conform to the Constitution. After the war, the Constitution was made to conform to the General Government, and Texas v. White, declaring secession unconstitutional, was just one of the many rotten fruits that fell from the corrupt tree of Radical Reconstruction. Thomas Jefferson warned of it at least as far back as 1820:

You seem … to consider the judges as the ultimate arbiters of all constitutional questions; a very dangerous doctrine indeed, and one which would place us under the despotism of an oligarchy. Our judges are as honest as other men, and not more so. They have, with others, the same passions for party, for power, and the privilege of their corps. Their maxim is “boni judicis est ampliare jurisdictionem” [good justice is broad jurisdiction], and their power the more dangerous as they are in office for life, and not responsible, as the other functionaries are, to the elective control. The Constitution has erected no such single tribunal, knowing that to whatever hands confided, with the corruptions of time and party, its members would become despots… (7)

This warning became prophesy during the Radical Reconstruction after the war, when Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase followed Lincoln’s lead in the exercise of arbitrary power.

So who was Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase and how did he come to theopinion that secession was unconstitutional in Texas v. White in 1869? Chase was well-known as a Radical Republican (8) who had been Lincoln’s Secretary of the Treasury and who had called for military action against Ft. Sumter (9). He evidently was a man of expediency when it came to money. In 1862 he endorsed Lincoln’s government-created fiat money known as “greenbacks” to finance the war, but the Money Trust on Wall Street didn’t like greenbacks because they couldn’t control the money supply or make any money off of them. So Wall Street sent Secretary of the Treasury Chase to Congress to “recommend” the creation of the Second National Bank of 1864, which would undercut the greenbacks and sell the monetary independence of the United States Government to the Money Trust. Chase engineered the sellout, and Lincoln got rid of him by making him Chief Justice of the Supreme Court in 1864. (10)

Salmon P. Chase was a blessing to Wall Street as Secretary of the Treasury. Now, as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, what other favours could he bestow? He could rule secession unconstitutional for them. The Money Trust well knew what secession could do to their finances. On the one hand, hatred ginned up by their financing Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the Dred Scott case, “Bleeding Kansas,” John Brown’s Raid, and the media and the politicians who fanned these flames, had brought on secession. Lincoln’s war had in turn brought them wealth from bonds issued to finance it (11). On the other hand, States that had seceded could repudiate their debts if they won their independence, and the banks would not be able to foreclose on them. But that was not the worst of it: in the middle of the nineteenth century cotton was “King,” and if the “Cotton Kingdom” were allowed to secede from the Union and set up as a free-trading Confederation on her southern doorstep, the North’s “Mercantile Kingdom” would collapse (12). So Lincoln had launched his armada against Charleston to provoke the Confederacy into firing the first shot to get the war he wanted, and after four years of the bloodiest war in the history of the Western Hemisphere, he had finally succeeded in driving the “Cotton Kingdom” back into the Union, but it had been a close thing. Now, with Radical Reconstruction cementing the Southern States back under the control of the North with the Army of Occupation and “carpetbagger” governments, and with the Fourteenth Amendment ratified by bayonet forcing the Southern States to repudiate their own war debt and finance the Union’s (13), there only lacked a ruling by the Supreme Court to make secession unconstitutional to put the icing on the cake of conquest, and Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase was their man.

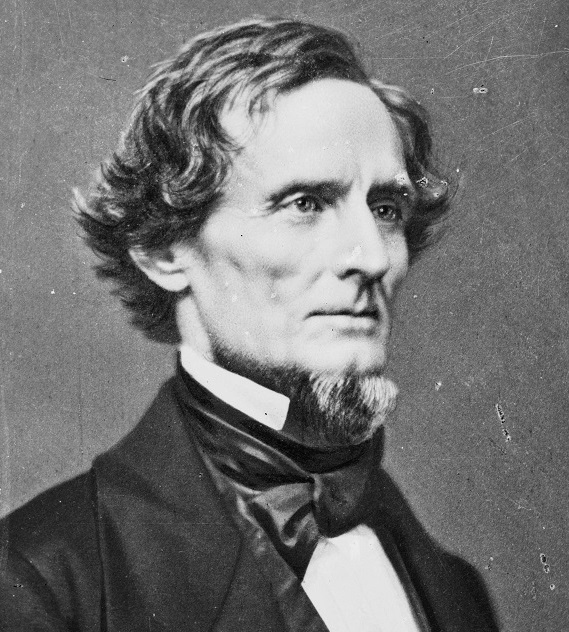

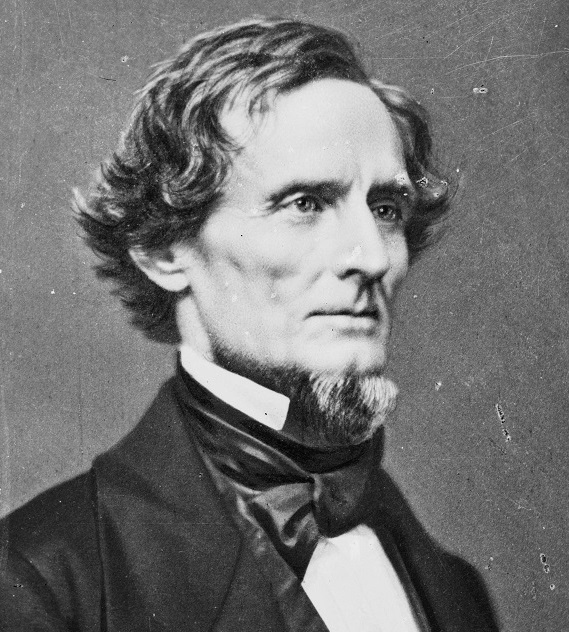

Chase was to try Confederate President Jefferson Davis – who was imprisoned in chains at Ft. Monroe – for treason, but the civil courts had been restored and prosecutors started dragging their feet. They feared that charges of treason against Davis would expose them to the great secessionist tradition of America, the Declaration of Independence, and to the Tenth Amendment to the Constitution. It might also bring up the fact that Abraham Lincoln, who had not recognized the Confederate States as being out of the Union, had committed treason under Article III, section 3 of the Constitution when he invaded them. If this were to happen, it would expose Lincoln’s War as a war of conquest rather than a war to suppress a rebellion, so Chief Justice Chase quietly dropped the case on a technicality (14).

While the chance was missed in the case of Jefferson Davis, Chase had another opportunity in the case of Texas v. White in 1869. It involved ten million dollars of bonds given to Texas during the Compromise of 1850. Radical Reconstruction was still in full swing, with the Southern States in the Union for the sake of plunder, but out of the Union for any Constitutional redress. The North’s astronomical national debt had to be collected, and the Wall Street Money Trust stood to lose money if Texas was ruled to be out of the Union – just as the North’s “Mercantile Kingdom” would have suffered financial disaster if the South’s “Cotton Kingdom” were out of the Union. The Chief Justice, using the specious arguments of Daniel Webster, ruled that since the Articles of Confederation made the Union under the Confederation “perpetual,” and the Preamble of the Constitution made the Union “more perfect,” therefore the Union was an “indestructible Union of Indestructible States.,” which made secession unconstitutional (15).

The Union under the old Articles of Confederation was indeed deemed “perpetual”, yet the States in that Union seceded from it under Art. VII of the Constitution of the new and “more perfect” Union. As John Remington Graham, former law professor, experienced trial lawyer, and specialist in British, American, and Canadian constitutional law and history, wrote in his work Blood Money: “The Union is perpetual, as a corporation can be perpetual, which means only that it is not limited by a term of years, and so will last forever unless lawfully dissolved.” He goes on to say that under the “more perfect” Union created by the new Constitution, “[n]o longer may secession be effected by legislative act of a State as under the Articles of Confederation. Under the intended meaning of the United States Constitution, only the people of a State in convention may effect withdrawal from the Union, which, consequently, is more perfect.” (16)

Thomas Jefferson would have agreed. He wrote:

[T]he several States composing the United States of America, are not united on the principles of unlimited submission to their General Government; but that by compact under the style and title of a Constitution for the United States and of amendments thereto, they constituted a General Government for special purposes, delegated to that Government certain definite powers, reserving each State to itself, the residuary mass of right to their own self Government… [T]he Government created by this compact was not made the exclusive or final judge of the extent of the powers delegated to itself; since that would have made its discretion, and not the Constitution, the measure of its powers…(17)

Having just won their independence from Great Britain, the citizens of the new Republic could hardly have been expected to entrust their hard-won liberties to a half-dozen black-robed lawyers appointed for life by some politician. But that all changed with Lincoln’s revolution. With the Supreme Court as the final arbiter of all Constitutional questions, including those limiting the powers of the Federal Government, and with the Supreme Court being part of the Federal Government, the Federal Government, therefore, is the final arbiter of the limits of its own power, and that, said Jefferson, is the very definition of despotism. Instead of offering his specious opinion for the unconstitutionality of secession in Texas v. White, Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase could have simply said “Secession is treason because we won the war.”

Notes

- The Works of Tennyson: With Notes by the Author. Ed with memoir by Hallam, Lord Tennyson (New York: The Macmillan Co., 1932) pg. 385.

- Charles W. Eliot LL D, ed. The Harvard Classics. 50 vols. Vol. 43, American Historical Documents (New York: P. F. Collier & Son, 1910) pgs. 160-1.

- Virginia Commission on Constitutional Government. We the States: An Anthology of Historic Documents and Cammentaries thereon, Expounding the State and Federal Relationship (Richmond: The Wm. Byrd P, 1964) pgs. 70-1.

- Ibid. pgs. 75-6.

- Charles Adams. When in the Course of Human Events: Arguing the Case for Southern Secession (Lanham. Boulder. New York. Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2000) pgs. 14-6.

- Thomas J. DiLorenzo. The Problem with Lincoln (Washington, D.C.: Regnery History, 2020) pgs. 75-93.

- Jefferson to William Charles Jarvis, September 28, 1820, in We the States, pg. 258.

- Philip Leigh. Southern Reconstruction (Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing, 2017) pg. 52.

- Adams, pg. 66.

- John Remington Graham. Blood Money: The Civil War and the Federal Reserve (Gretna: Pelican Publishing Co., 2012) pgs. 60-4. Also, G. Edward Griffin. The Creature from Jekyll Island: A Second Look at the Federal Reserve, 4th ed. (1994; Westlake Village, CA: American Media,2002) pgs. 384-6.

- Graham, pgs. 29-50.

- Gene Kizer, Jr. Slavery Was Not the Cause of the War Between the States: The Irrefutable Argument (Charleston and James Island: Charleston Athenaeum P, 2014) pgs. 35-7.

- Graham, pgs. 51-2.

- Adams, pgs. 177-180.

- Graham, pgs. 64-6.

- Ibid, pgs. 66-7.

- Thomas Jefferson. The Kentucky Resolutions, 1798, in We the States, pgs. 143-4.