July 4, “Independence Day,” has become for most Americans little more than another holiday, a day off from work, and a time to barbecue with family and friends.

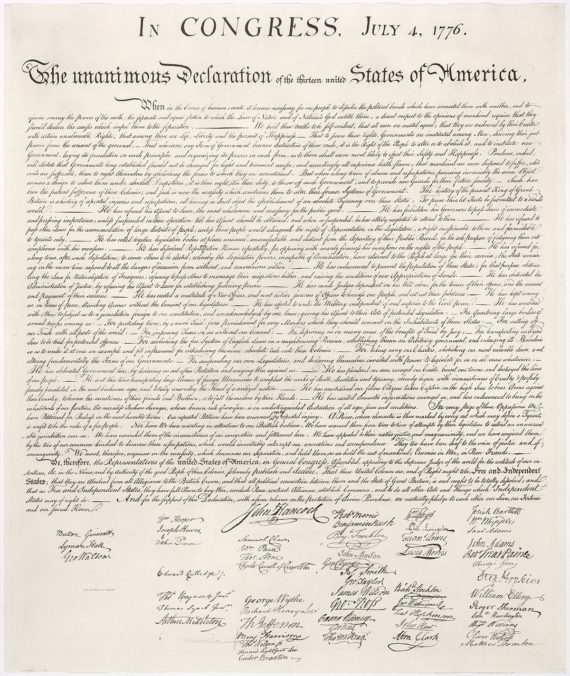

Yet, the Declaration of Independence and the day we set aside to commemorate it should make us reflect on the sacrifices of the men who signed it and what they intended. Representatives from thirteen colonies came together to take a momentous step that they knew might land them on the scaffold. They were protesting that their traditional rights as Englishmen had been violated, and that those violations had forced them into what was actually in many ways America’s real “civil war”: English subjects in America against the English government at Whitehall.

For many the Declaration of Independence is a fundamental text that tells the world who we are as a people. It is a distillation of American belief and purpose. Pundits and commentators, left and right, never cease reminding us that America is an “exceptional” nation, “conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.”

Almost as important as a symbol of American belief, we are instructed, is Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address. Lincoln intentionally places his short peroration in the context of a particular reading of the Declaration. He bases his concept of the creation of the American nation in philosophical principles he sees enunciated in 1776, and in particular, on the idea of “equality” and a new national unity undreamt of by earlier generations. With this understanding, he charts a new and radical departure: “this nation…shall have a new birth of freedom,” an open-ended invitation to future revolutionary change.

In his view, America is a nation whose unbreakable unity supersedes the recognized and prior rights of the states and which finds that unity in “mystic chords of memory.” The problem is that this interpretation, which forms the philosophical base of both dominant “movement conservatism” today – neoconservatism – and the post-Marxist multicultural Left, is basically false.

Lincoln opens his address, “Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth ….” There is a critical problem with this assertion. It was not the Declaration that “created” the new nation; the Declaration was a statement of thirteen individual colonies, announcing their respective independence from the mother country, binding themselves together in a military and political alliance. It was the Constitution, drafted eleven years later (1787), after the successful conclusion of the War for Independence, which established a new nation. And, as various historians and scholars have pointed out, in 1776 the American Founders never intended to cobble together a nation with a unitary government based on the proposition that “all men are created equal.”

A brief survey of the writings of such distinguished historians and researchers as Barry Shain, Forrest McDonald, M. E. Bradford, George W. Carey, and more recently Kirkpatrick Sale, plus a detailed reading of the commentaries and writings of those men who met in Philadelphia, give the lie to that claim.

The Framers of the Constitution were horrified by “egalitarianism” and “democracy,” and they made it clear that what they were establishing in 1787 was a limited republic, which owed its existence to certain powers conceded by the respective states, a republic in which most “rights” were retained zealously by the states, including the inherent ability to decide who would participate in governing and on what basis. The Tenth Amendment, too often overlooked or disregarded, spells that out: “The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.”

A survey of the correspondence and the debates over the Constitution and its meaning underscores support for this regionalism and anti-egalitarianism, as Professor Bradford methodically demonstrates in his volume Original Intentions: On the Making and Ratification of the United States Constition and also in Founding Fathers: Brief Lives of the Framers of the United State Constitution.

Obviously, then, Lincoln could not found his “new nation” on the U. S. Constitution; it was too aristocratic and decentralized, with non-enumerated powers maintained by the states, including the implicit right to secede (admitted by almost the entirety of constitutional interpretation prior to 1861). Indeed, slavery was explicitly sanctioned, even if most of the Framers believed that as an institution it would die a natural death, if left on its own.

Lincoln went back to the Declaration of Independence and invested in it a meaning that supported his statist and wartime intentions. But even then, he verbally abused the language of the Declaration, interpreting the words in a form that its Signers never envisioned or intended. Although those authors employed the phrase “all men are created equal,” and certainly that is why Lincoln made direct reference to it, a careful analysis of the Declaration does not support the sense that Lincoln invests in those few words. (See the Professor Shain’s detailed examination, The Declaration of Independence in Historical Context: American State Papers, Petitions, Proclamations, and Letters of the Delegates to the First National Congresses). Contextually, the authors at Philadelphia were asserting their historic — and equal — rights in law as Englishmen before the Crown, which had, they believed, been violated and abused by the British government.

Like the Framers, the Founders rejected egalitarianism. They understood that no one is, literally, “created equal” to anyone else. Certainly, each and every person is created with no less or no more dignity, measured by his or her own unique potential before God. But this is not what most contemporary writers mean today when they talk of “equality.”

Rather, from a traditionally-Christian viewpoint, each of us is born into this world with different levels of intelligence, in different areas of expertise; physically, some are stronger or heavier, others are slight and smaller; some learn foreign languages and write beautiful prose; others become fantastic athletes or scientists. Social customs and traditions, property holding, and individual initiative — each of these factors further discriminate as we continue in life.

None of this means that we are any less or more valued in the judgment of God, Who judges us based on our own, very unique capabilities. God measures us by ourselves, by our own maximum potential, not by that of anyone else — that is, whether we use our own, individual talents to the very fullest (recall the Parable of the Talents in the Gospel of St. Matthew).

The Founders understood this, as their writings and speeches clearly indicate. Lincoln’s “new birth of freedom” would have certainly struck them as radical and revolutionary, a veritable “heresy.” Even more disturbing for them would be the specter of the modern-day neoconservatives — that is, those who purport to defend our Constitutional republic against the abuses of the multiculturalist left — enshrining Lincoln’s address as a basic symbol of American political and social order.

They would have understood the radicalism implicit in such a pronouncement; they would have seen Lincoln’s faulty interpretation of the Declaration as grafting on to the Constitution a meaning which it does not have and, in fact, a revolutionary denial of its original intentions; and they would have understood in Lincoln’s language the content of a Christian and millennialist heresy, heralding a transformed nation where the Federal government would become the father and mother and absolute master of us all…all in the name of “our democracy.”

Thus, as we commemorate the declaring of American independence 245 years ago, we should lament the mythology created about it in 1863. And we should recall the generation of 1787, a generation of noble men who comprehended fully well that a country based on the centralization of power in the abusive hands of a few and on egalitarianism is a nation where true liberties are imperiled.

In 2021 we have reached a nadir in our history, nearly as defining as the defeat on the battlefield of the older constitutional republicanism in 1865. The expressed fears of the Framers have been fully realized. The hopes of our ancestors have been turned into nightmares for us, their progeny.

It is time for patriots to once again invoke the name of “God, Our Help in Ages Past” and, each in his own manner, mount the barricades.

When it comes to the US Constitution, some us think that Abraham Lincoln was an Originalist.

My sincere compliments for another fine article. And, I am not even from the South, although my father was born and raised in Maryland.