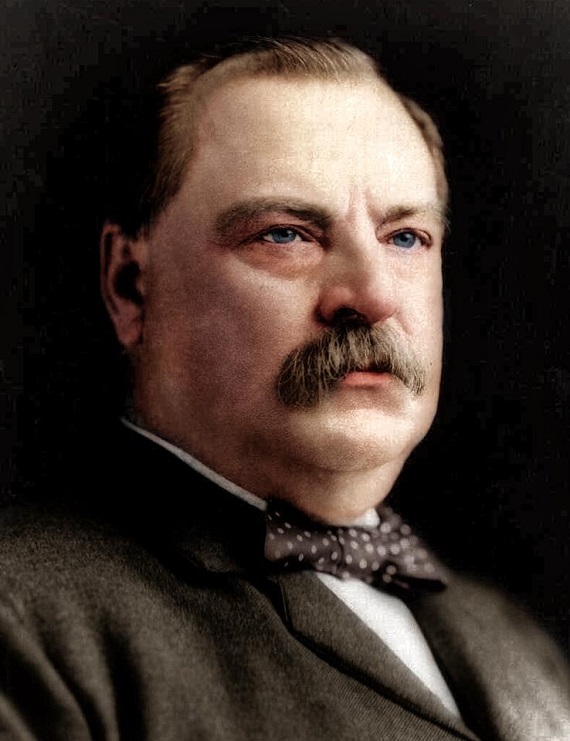

From Ryan Walters, Grover Cleveland: The Last Jeffersonian President (Abbeville Institute Press, 2021).

“Equal and exact justice to all men, of whatever state or persuasion, religious or political.” Thomas Jefferson[i]

“I have faith in the honor and sincerity of the respectable white people of the South. … I am a sincere friend of the negro.” Grover Cleveland[ii]

On March 4, 1885, the long-ruling Republicans watched a Democrat take the oath of office for the first time since 1857. Since James Buchanan gave way to Abraham Lincoln four years later, a quarter century of GOP rule, resulting in corruption, profligate spending, high taxes, and ever-expanding government, had become the norm. Republicans had used the absence of the Jeffersonian South to re-make the country as they desired, implementing programs and policies that Southerners had always rejected.

Lincoln and his party, in the Revolution of 1861, militarily conquered the South in four years and controlled most of the region until 1877 when the final Union troops were removed, thus allowing them to opportunity to rule as they chose. After 1877, Northern leaders shamed the rest of the country into keeping Republicans in power. And in all that time the South lagged far behind, both economically and politically. Before the war, the South possessed the richest states in the Union, while Southerners dominated the national government; after the defeat of the Confederacy, the South did not produce a single national leader for the remainder of the century and fell to last place in wealth. The political shunning stemmed mainly from the North’s great anger over the war and the continued use of their oft-used “bloody shirt” tactics to win elections.

But on a spring day in 1885 the sun shone brightly on the South, as a Jeffersonian Democrat became the nation’s 22nd president. And Southerners were overjoyed about having a Jeffersonian in the White House. The inauguration was festive, as Southerners came in large numbers, bands played “Dixie,” and a former Confederate general rode in the inaugural parade. One reporter from the Atlanta Constitution noted a “feeling here to-night stronger than I ever saw it before, that the war is over.” This was not necessarily a reference to the actual violent war that concluded twenty years before but the quarter century political war, as one Democratic official declared, “The election of Grover Cleveland to the Presidency of the United States marks the dawn of a new era in our national history.” It would be an era when the South was, once again, back in the Union as an equal partner.[iii]

A friend of Jefferson Davis wrote to the former Confederate president upon reading Cleveland’s inaugural address in the newspaper, joyous that the new chief executive “will be the nearest approximation of ‘Old Hickory’ since the Civil War.” Indeed, Cleveland, like Andrew Jackson, was seen as a fearless president for the common man. “Cleveland is a man of the people,” wrote the Atlanta Constitution. “He combines more fully than any other man the elements of reform, and that the people feel they can safely look to him for the ability to plan reforms in public affairs and the courage to carry them out.”[iv]

Down in New Orleans, the Daily Picayune editorialized that “Mr. Cleveland is a popular favorite. He is the people’s candidate. No man, in manner and utterance, is farther for being a demagogue. He seems to be talking to the people and for the people. No man in the country today is more beloved by the masses of the people, and the secret of it is that they believe he is their friend.”[v]

The South also saw in Cleveland a president who could heal the sectional divide, a decades-long rift that had yet to mend due to the seemingly never-quenching anger in the North. Henry Watterson, the editor of the Louisville Courier-Journal, penned an article for the North American Review just three months before Cleveland’s first inauguration entitled “The Reunited Union.” Watterson’s hope was for sectional reconciliation. “The election of Mr. Cleveland to the Presidency,” he wrote, “sweeps away all sectional distinctions and lines. It brings the South back into the Union and the Administration. It gives it the opportunity, which it ought to embrace, of impressing itself upon the national policy. It invests it with actual power and the responsibility that belongs to power, and bids it show its real character as a political entity and force.”[vi]

The South certainly had that hope. The Telegraph and Messenger of Macon, Georgia was sincerely hopeful that the election of Grover Cleveland “had killed sectionalism,” although a number of Southerners did not buy it simply because they did not believe the more radical element in the North would ever allow it. But many had faith, like the North Carolina Tar Heel Josephus Daniels, who would later serve in the Woodrow Wilson Administration as Secretary of the Navy. He praised Cleveland as “the Democratic Moses who would lead his party into the Promised Land.” His election as president “gladdened and heartened the people of the South. They felt they were back in the Union their fathers had helped to found and could again sit down at the government table as equals.” Cleveland would end “the exclusion of Southern men from a voice in the government of their country.”[vii]

This same biblical theme was on the mind of a young Missouri politician named Champ Clark, a future House Speaker and presidential candidate, who first came to Congress during Cleveland’s presidency. Clark also thought of Cleveland as “the Moses of Democracy who had led them through the Red Sea and the Wilderness into sight of the Promised Land, but also the Joshua who had brought the safely into Canaan, flowing with milk and honey.”[viii]

Another young North Carolina journalist, Walter H. Page, who would later serve as ambassador to Britain under Woodrow Wilson, described Cleveland as “an honest, plain, strong man, a man of wonderfully broad information and of most uncommon industry. He has always been a Democrat. He is a distinguished lawyer and a scholar on all public questions. He is as frank and patriotic and sincere as any man that ever won the high place he holds. He is as unselfish as he is great.”[ix]

When Cleveland named Hoke Smith of Atlanta to the Cabinet, an attorney from Los Angeles wrote his congratulations. “I am proud that we have an incoming administration of the affairs of the Government that will give the South an opportunity to show the Nation that the Southern boys are able to take their stand among the great Statesmen of our country.” With such a man as Grover Cleveland “at the head of affairs, and with such advisers as he is placing around him, I am sure that our party, and our cause can not fail.”[x]

And Grover Cleveland was as good as his word. Just as Watterson had written, Cleveland did desire sectional reconciliation, to bring the South back into the Union as an equal, to end the strife and division that had been ongoing for decades, and to roll back everything the Republicans had done for the previous twenty-five years. To the South he wanted to assure “good government to the people and complete reconciliation between all sections of the land.”[xi]

In the first act of bringing the South more fully into the government, President Cleveland named two dyed-in-the-wool Southerners to the Cabinet and, for the most important cabinet post, that of secretary of state, he named a strong Southern sympathizer. The South had virtually no representation in the executive branch since before the war, with the only post-war exception being David M. Key of Tennessee, named Postmaster General by Rutherford B. Hayes, an appointment made only as part of the Compromise of 1877 that handed Hayes the White House in the disputed election with Samuel J. Tilden.

Cleveland’s two Southern nominees, though, were not just typical politicians who just happened to reside south of the Mason-Dixon Line; he chose two prominent ex-Confederates, and high-ranking ones at that. For attorney general, the new president named Augustus H. Garland of Arkansas, who did not serve in the Confederate army but in both houses of the Confederate Congress. After the war, Garland had to fight for his right to resume the practice of law, since the US Congress, in an act passed in 1865, banned former Confederates from the bar. The case, Ex parte Garland, made it to the US Supreme Court, which, after hearing Garland’s arguments, struck down the act as an unconstitutional Ex Post Facto law. Denied the right to serve in the US Senate in 1867, Garland was elected to the governorship in 1874, and after Reconstruction was able to take a seat in the US Senate in 1877.[xii]

Cleveland’s other choice would lead the Interior Department, Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus Lamar of Mississippi, a long-serving statesman later featured in John F. Kennedy’s Pulitzer Prize-winning book, Profiles in Courage. Lamar had high hopes for Cleveland and stumped for him during the 1884 campaign. “I think that the interests of the South are with the country at large in voting for Cleveland,” he said in one speech.[xiii]

Before the war, Lamar had been a professor of mathematics at the University of Mississippi, then a member of the US House until the election of Lincoln. He then resigned from Congress to serve as a delegate in the Mississippi Secession Convention. And while serving in that capacity, Lamar wrote the secession ordinance that withdrew Mississippi from the Union. During the war he served in the Confederate army as a colonel and was later sent on several diplomatic missions for President Davis on behalf of the Confederate government. After the war, he served in the US House once again, then a term in the US Senate before receiving the call from President Cleveland.[xiv]

But Lamar would see promotion once again during Cleveland’s first term. In the summer of 1887, upon the death of Justice William B. Woods, Cleveland created another political firestorm when he named Lamar to the vacancy on the US Supreme Court. Naming such a prominent former Confederate to the cabinet was one thing; but naming him to a lifetime seat on the High Court would be a different matter, for the North would almost certainly oppose his confirmation with a vengeance. Yet in Cleveland’s mind this was another important step in bringing the South more fully into the Union.

Senator George F. Hoar, a fierce Northern Republican from Massachusetts who would vote against him, personally liked Lamar, calling him “one of the most delightful of men,” who was “far-sighted” and possessed “infinite wit and a great sense of humor.” Lamar, though, was the quintessential Southerner of his day, a man who believed it “was a great misfortune for the world that the Southern cause had been lost.” Yet, despite that opinion, Hoar admired him. “He stood by his people,” he wrote of Lamar in his memoirs, “in their defeat and in their calamity without flinching or reservation.” And Hoar believed that Lamar “desired most sincerely the reconciliation of the sections, that the age-long strife should come to an end and be forgotten, and that the whole South should share the prosperity and wealth” of the country.[xv]

The opposition to Lamar did not arise simply because he was from the South, at least that’s what many Northerners claimed, or because they did not believe he was a decent man. For Senator Hoar, his opposition was “not because I doubted his eminent integrity and ability, but because I thought that he had little professional experience and no judicial experience.” Other Senators, like Shelby M. Cullom of Illinois, expressed a similar sentiment. Yet this excuse for opposition seems untruthful, as five of the Court’s sitting justices at the time also had no prior judicial experience.[xvi]

Republican newspapers also attacked Lamar’s nomination with a vengeance, but not so much with the “bloody shirt,” the age-old Northern campaign device of reminding voters of the late war and those they said had started it. Instead, like Northern Senators, they used other tactics. The Chicago Tribune assailed Lamar’s views on labor, while the San Francisco Chronicle believed Lamar leaned “naturally and spontaneously to the side of the strong against the weak. He is a friend of monopolies.” Much of the GOP opposition stemmed from the belief that Lamar would interpret the Constitution, not with a nationalistic viewpoint to which Republicans were accustomed, but with one leaning toward the old strict, state’s rights construction.[xvii]

Despite the political protests, Cleveland knew Lamar’s quality. During the confirmation fight, he told Henry W. Grady of the Atlanta Constitution that Lamar “cannot decide a thing wrong. His temperament is such that when he considers a question he is obliged to decide it right. I have never seen this quality so marked in any other man.” And the president lobbied hard for his confirmation. After months of Senate foot-dragging, he asked Senator Cullom of Illinois to help speed the process along so he could find a replacement for Interior. “I wish you would take up Lamar’s nomination and dispose of it. I am between hay and grass with reference to the Interior Department. Nothing is being done there; I ought to have some one on duty, and I can not do anything until you dispose of Lamar.”[xviii]

Cleveland did get some help from the other side of the isle. Senator William M. Stewart of Nevada, a Silver Republican, thought Northern rejection of Southerners amounted to discrimination and did not believe Lamar’s status as a former Confederate should disqualify him. “The Judiciary Committee found him otherwise qualified,” he wrote, “but reported that his participation in the rebellion ought to prevent his confirmation.” Should the Senate reject him for this reason, it would set “a direct precedent for the rejection for any Federal office of every man in the South who had participated in the rebellion,” which was most likely what the North had in mind. Stewart favored Lamar’s confirmation and was pleased when the Senate finally gave its consent, saving it “from the disgrace of granting amnesty and then withdrawing it; and of pledging equality of civil and political rights and afterward violating that pledge.”[xix]

Despite the fierce Northern opposition, including Cullom and Hoar, the Senate confirmed Lamar by the narrow margin of 32 to 28 on January 16, 1888, making him the only Mississippian to sit on the United States Supreme Court. Writing years later, Senator Hoar admitted that he had “made a mistake” in opposing the Mississippian and former Confederate. Though he did not serve on the High Court for long, just five years, Justice Lamar “wrote a few opinions which showed his great intellectual capacity for dealing with the most complicated legal questions,” Hoar wrote. Lamar left his post only with his death on January 23, 1893.[xx]

For secretary of state, Cleveland named Senator Thomas F. Bayard, Sr., a member of the famed Bayard family from Delaware. And Bayard’s family was truly remarkable:

His great-grandfather, Richard Bassett, signed the Constitution. His grandfather, James A. Bayard, the elder, served in both the House of Representatives and the Senate and cast the deciding vote for Thomas Jefferson in the 1800 election. His uncle, Richard H. Bayard, served in the Senate and as charge d’affaires to Belgium. His father, James A. Bayard, the younger, served in the Senate and resigned his seat in 1864 due to his manly opposition to the Lincoln administration but later accepted another appointment in time to cast a negative vote in the Andrew Johnson impeachment trial.

Though not a Southerner in the traditional sense, Bayard assumed his father’s seat in the US Senate in 1869 and was very sympathetic to Southerners, opposed what he called the “Radical Party” in the North and its “wretched catalogue of wrongs” inflicted upon the South, and held true to Jeffersonian principles of government. The South could only be too happy about Cleveland’s choice of Bayard. As Brion McClanahan has written, while in the Senate, the “Southern delegation respected Bayard for good reason. He was one of them, a man who understood the Republican regime to be the antithesis of American political principles.”[xxi]

In his second term, Cleveland named two more Southerners of the Old Confederacy to his Cabinet. William L. Wilson of Virginia, who had previously served twelve years in the US House from a West Virginia district and who authored the controversial Wilson-Gorman Tariff Act of 1894, was named postmaster general. Wilson was one of Cleveland’s favorites and the president spent a great deal of time with him at the White House discussing a litany of issues.[xxii]

The other was Hilary A. Herbert, an eight-term Alabama congressman who would head the Navy Department. Herbert greatly admired Cleveland for the courage and “unflinching tenacity with which he held to his beliefs.” He also praised Cleveland for helping to end sectionalism by bringing North and South more closely together. Many historians contend that the event that did the most to heal sectional bitterness was the Spanish-American War in 1898 because, for the first time since the Mexican War in the 1840s, Northerners and Southerners fought together on the same side. But for Herbert it was, in actuality, Cleveland’s invocation of the Monroe Doctrine in 1895 in a dispute with Britain over Venezuela. President Cleveland’s message, wrote Herbert, “struck a cord in the hearts of Congressmen from the North and the South that caused them to stand together for their country as one man.”[xxiii]

**************

[i] Jefferson, First Inaugural Address, March 4, 1801.

[ii] Grover Cleveland, Address to Southern Educational Association, New York City, April 14, 1903, in Grover Cleveland: Addresses, State Papers, and Letters, edited by Albert Ellery Bergh (New York: The Sun Dial Classics Co., 1909), 423-424.

[iii] R. Hal Williams, “‘Dry Bones and Dead Language’: The Democratic Party,” in H. Wayne Morgan, ed., The Gilded Age (Syracuse, 1970), 129.

[iv] E. G. W. Butler to Jefferson Davis, March 7, 1885, in Jefferson Davis, Constitutionalist: His Letters, Papers, and Speeches, edited by Dunbar Rowland (Jackson, MS: Mississippi Department of Archives and History, 1923), IX, 350; Atlanta Constitution, July 12, 1884.

[v] New Orleans Daily Picayune, June 23, 1892 and July 20, 1892.

[vi] Henry Watterson, “The Reunited Union,” North American Review (January 1885), 22-30.

[vii] Macon Telegraph and Messenger quoted in a letter from Chas. Herbst to Jefferson Davis, April 3, 1885, in Rowland, Davis, Constitutionalist, Volume 9, 360-362; Josephus Daniels, Tar Heel Editor (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1939), 200.

[viii] Champ Clark, My Quarter Century of American Politics, 2 volumes (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1920), II, 231.

[ix] Burton J. Hendrick, The Life and Letters of Walter H. Page, 2 volumes (New York: Doubleday, 1923), I, 40.

[x] J. H. Johnson to Hoke Smith, February 16, 1893, in Hoke Smith Papers, University of Georgia.

[xi] Cleveland to the People of Charleston, South Carolina, June 18, 1886, in Allan Nevins, ed., Letters of Grover Cleveland, 1850-1908 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1933), 113-114.

[xii] Leonard Schlup, “Augustus Hill Garland: Gilded Age Democrat,” Arkansas Historical Quarterly (Winter, 1981), 338-346.

[xiii] Edward Mayes, Lucius Q. C. Lamar: His Life, Times, and Speeches, 1825-1893 (Nashville, TN, 1896), 454.

[xiv] Ibid.

[xv] George F. Hoar, Autobiography of Seventy Years. 2 volumes (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1903), II, 177.

[xvi] Hoar, 177; Shelby M. Cullom, Fifty Years of Public Service: The Personal Recollections of Shelby M. Cullom (Chicago: A. C. McClurg & Co, 1911), 227.

[xvii] Willie D. Halsell, “The Appointment of L. Q. C. Lamar to the Supreme Court,” Mississippi Valley Historical Review (Dec. 1941), 403-404.

[xviii] Henry W. Grady to Lamar, October 29, 1887, Mayes, 521; Cullom, 277.[xix] William M. Stewart, Reminiscences of William M. Stewart of Nevada, Edited by George Rothwell Brown (New York, 1908), 308-309.

[xx] Cullom, 277; Hoar, 177.

[xxi] Brion McClanahan, “Thomas F. Bayard, Sr.,” Abbeville Institute Review, https://www.abbevilleinstitute.org/blog/thomas-f-bayard-sr/.

[xxii] Festus P. Summers, ed., The Cabinet Diary of William L. Wilson, 1896-1897 (Chapel Hill, 1957), vii.

[xxiii] Hilary A. Herbert, “Grover Cleveland and His Cabinet At Work,” Century Magazine, March 1913, 740-744.

I am so glad to see the article commending Grover Cleveland. I have been an admirer of him for a long time. I think President Cleveland and President Buchanan have been the most under rated of all the presidents. Apparently, the South haters ignore him, because of is honesty and fair treatment of all Americans. Thank you so much for advancing his reputation. It is refreshing to read history that is truthful, not just made up yesterday.

Herbert also commanded the 8th Alabama, in which two of my people served. He assembled a history of the regiment which was published by the Alabama Historical Review.