Delivered at the 2013 Abbeville Institute Summer School.

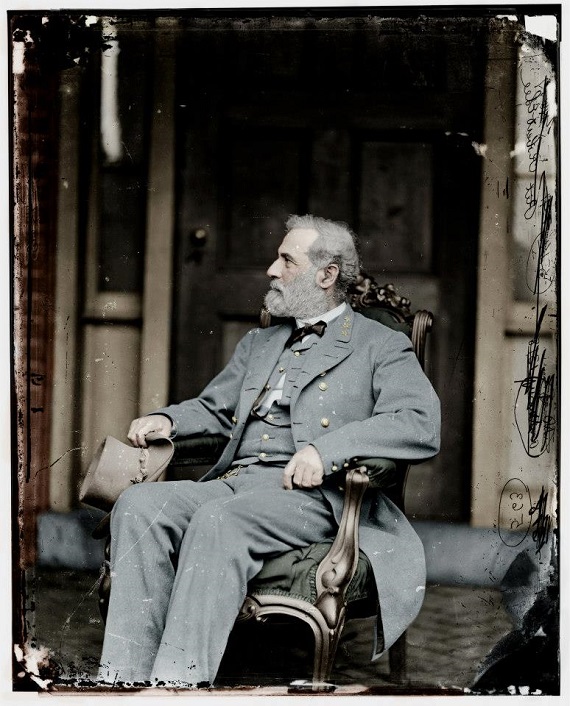

What I want to do is thoroughly cover Lee in his time and in ours, and try to understand that transformation. There’s more there than meets the eye, and it has to do with our understanding of Lee. If we can understand the transformation as carefully as I hope to take us through it, then we can really understand Lee and his time and Lee in ours. Even down to the use of the word hermeneutics. When [H.] Lee Cheek used that word, I said, “there’s a conspiracy,” because I was planning on using it too. It’s in a little joke that I was gonna use midway through. You’ll catch it, you’ll hear it; I’m gonna keep it in there. Hermeneutics, as Lee Cheek explained to you, means “theories of interpretation.” We’re gonna be looking at some theories of interpretation of Lee and some decisions that he made. I don’t really have time to deal a lot with Lee’s life. Just to get it out on the table: Lee was born in Westmoreland County, Virginia in 1807. Westmoreland County is what we call the Northern Neck. His father was Henry Lee, known as “Light Horse Harry.” When he was a young boy, he moved to Alexandria, [and later] attended West Point, where he was second in his class and did not incur a single demerit, which is, I believe, still a record. I don’t think anybody has ever done that except for Robert E. Lee. I want to begin with two quotations about Lee from his age, and then I’m going to look at one quotation, and then later in my talk, several quotations about Lee from ours. This first one is from a young woman who, by chance, happened upon Lee on a stairwell in a traveler’s lodge not far from Lee’s last home, which was the president’s home at Washington College, which is now, of course, Washington and Lee [University]. And this is what the lady says. (There’s just a chance happening and meeting him on the staircase). She said:

“The man who stood before us was the realized King Arthur. The soul that looked out of his eyes was as honest and fearless as when it first looked on life. One saw the character as clear as crystal without complications or seals, and the heart is tender as that of ideal womanhood. The years that have passed since that time have dimmed many enthusiasms and destroyed many illusions, but have caused no blush on the memory of that swift thrill of recognition and reverence which ran like an electric flash through one’s whole body.”

Just a chance encounter. She never saw him again. She saw him for one brief moment and years later, she wrote that down. The next [quotation] is going to come from volume four of Douglas Southall Freeman’s R.E. Lee: A Biography. It’s a great series of books. This four-volume biography doesn’t seem to, well, I don’t see it on as many Southern bookshelves as I’d like to see. This comes from years of studying Lee and this is just part of his final assessment. It’s rather long, but I want to get it out on the table. [To quote] Douglas Southall Freeman:

“To understand the faith of Robert E. Lee is to fill out the picture of him as a gentleman of simple soul. For him as for his grandfather, Charles Carter, religion blended with the code of noblesse oblige to which he had been reared. Together, these two forces resolved every problem of his life into right and wrong. The clear light of conscience and of social obligation left no zone of gray in his heart: everything was black or white. There cannot be said to have been a ‘secret’ of his life, but this assuredly was the great, transparent truth, and this it was, primarily, that gave to his career its consistency and decision. Over his movements as a soldier he hesitated often, but over his acts as a man, never. There was but one question ever: What was his duty as a Christian and a gentleman? That he answered by the sure criterion of right and wrong, and, having answered, acted. Everywhere the two obligations went together; he never sought to expiate as a Christian for what he ahead failed to do as a gentleman, or to atone as a gentleman for what he had neglected as a Christian. He could not have conceived of a Christian who was not a gentleman.

Kindness was the first implication of religion in his mind, not the deliberate kindness of good works to pacify some exacting deity, but the instinctive kindness of a heart that had been schooled to regard others. His was not a nature to waste time in the perplexities of self-analysis; but if those about him at headquarters had understood him better they might often have asked themselves whether, when he brought a refreshing drink to a dusty lieutenant who called with dispatches, he was discharging the social duty of a host or was giving a ‘cup of cold water’ in his Master’s name. His manner in either case would have been precisely the same.

Equally was his religion expressed in his unquestioning response to duty. In his clear creed, right was duty and must be discharged. ‘There is,’ he wrote down privately for his own guidance, ‘a true glory and a true honor: the glory of duty done — the honor of the integrity of principle.’…Had his life been epitomized in one sentence of the Book he read so often, it would have been in the words, ‘If any man will come after me, let him deny himself, and take up his cross daily, and follow me.’”

For Freeman, the incident that characterizes Lee perfectly: “occurred in Northern Virginia, probably on his last visit there. A young mother brought her baby to him to be blessed. He took the infant in his arms and looked at it and then at her and slowly said, ‘Teach him he must deny himself.’”

In narrating Lee’s funeral, Freeman therefore said: “there is no mystery in the coffin there in front of the windows that look to the sunrise.” His duty was what he willed, and what he willed was his duty. There is no secret. We can say that is Lee in his time. Now I would like to read from a contemporary historian who after (not as many) years of study of Lee comes up with this. This is professor Gary Gallagher, my colleague at the University of Virginia. This is his summation:

“The white man’s country. Most familiar to Robert E. Lee rested on a foundation of slavery. The country most familiar to Robert E. Lee rested on a foundation of slavery. Lee accommodated himself to a world without slavery after the war and, with less certain white dominance, only because the United States’ victory in a great war left him no alternative. In the end, his journey toward Confederate loyalty and unwavering service and pursuit of independence left him angry and disoriented, bereft of stability in an uncertain world. Slavery was taken away from him like you would snatch cigar out somebody’s mouth and left him bereft of stability. He was alienated in an uncertain world.”

Sorry this is in so many parts, but as I said, I had to do some reorganizing. Though we cannot saddle all admirers and all detractors of Robert E. Lee with these quotations, they do, I think, set forth the transformation of our picture of Lee (to use my title), from his time to ours: Southern Arthur to brilliant, but misguided, alienated white supremacist who led his nation to utter ruin and completely destroyed his own army. As Gallagher continued to say: “Everything that Lee loved and admired, he destroyed.” We can of course, account for this transformation in part, but only in part, by reminding ourselves that history books are written by the victors. But there is another reason. The picture of Lee from his time is blocked from entirely entering ours. Modern historians, for many decades now, have used the celebrity of “being on the right side of history,” to use that despicable phrase, to claim that only the evidence they put forward is true evidence, and what is more, is the only evidence that can be true. They have the right to say what’s evidence and what’s not evidence. The power of winning translates into the power of pontificating over evidence. This is what in an earlier lecture was called the “Lost Cause School” of history. Their warrant for this pronouncement is that any cogent case defending the Southern cause, including the nobility of her leaders, is merely a rear-guard action to demonstrate that the South did not fight to maintain a slavocracy, but for some other cause, be it States’ Rights, free trade, what have you.

Along with wearing the winners’ mantle goes the privilege of governing historiography itself. Whether there was this kind of retrospection is indeed beside the point. What is at issue is the assumed right to use the privilege and power of victory to judge all evidence and finding of modern scholarship (especially if it wants to give a good showing for the reasons the South went to war) as a rear guard retrospection trying to recast the story of why the South went to war to avoid the shame of slavery. It is not hard to detect, though, that this emperor has no clothes. For instance, the Reverend James Henley Thornwell warned a year before the War that the impending catastrophe would be like Louis XIV’s devastation of the Rhine Valley at the close of the 17th century. Now, if he had said that after the War, then that would be called “Lost Causing.” If he said this after the War, that’s “Lost Causing,” he [supposedly] is making it all up to cover over the facts. But he said it before the War. He said it before the War. What’s more, Thornwell died a year into the War. He had no chance to say anything after the War. There was no retrospection possible. And what do you do with the defense of the Southern cause written by Europeans such as the great military historian, G.F.R. Henderson, who did not, and do not now bear any shame of slavery, but are simply trying to write a valid account of the War? What do you do with them? [Henderson was] a late 19th-century military historian who wrote a brilliant biography of Stonewall Jackson. If you’ve not read it, please do.

The character of Robert E. Lee offers this scholarly despotism a very interesting new twist. Lee, of course, abhorred slavery, as we’ve heard several times from this podium. He never owned a slave and faithfully executed his father-in-law’s will freeing more than 173 slaves. That he would join a war simply to perpetuate slavery is unthinkable. But more importantly, when the seven states of the lower south seceded, here comes the foil to the “Lost Causers” when it comes to Lee. When the seven Lower-South states seceded, Lee was completely opposed and said so numerous times. He called it a rebellion and completely uncalled for. As he wrote in 1861:

“Secession is nothing but revolution. The framers of our constitution never exhausted so much labour, wisdom, and forbearance in its formation and surrounded it with so many guards and securities if it was intended to be broken by every member of the confederacy at will. God alone can save us from our folly, selfishness, and shortsightedness. The last account seemed to show that we have barely escaped anarchy to be plunged into civil war. What will be the result, I cannot conjecture. I only see that a fearful calamity is upon us and fear that the country will have to pass through for its sins a fiery ordeal.” (Lee thought the war could easily take ten years, at this point). “I am unable to realize that our people will destroy a government inaugurated by the blood and wisdom of our Patriot fathers that has given us peace and prosperity at home. The Union was intended for a perpetual union, so expressed in the preamble [of the U.S. Constitution].”

It’s interesting. Lee is a soldier, schooled at West Point. He makes an error. The Constitution does not say “a perpetual union.” That is said in the Articles [of Confederation]. So, he’s a little confused here, but watch as his mind over time begins to unravel and he strikes upon the correct point. But here he thinks: “intended for a perpetual union, so expressed in the preamble, and for the establishment of a government, not a compact.”

How are you gonna get this guy on “Lost Causing?” Where are you gonna get it?

“…not a compact, which can only be dissolved by revolution or the consent of all the people in convention assembled. It is idle to talk of secession anarchy would have been established, and not a government, by Washington, Hamilton, Jefferson and Madison, and the other Patriots of the Revolution.”

He does say: “Still, a union that can only be maintained by swords and bayonets and in which strife and civil war are to take the place of brotherly love and kindness has no charm for me.” He can say that, but this did not cause him to turn and embrace the secession movements. Despite his stern objections to Northern policies against the South, he stuck by his principles. He stuck by what Dr. Livingston asked us to call “the Union in the abstract, the Union as it’s meant to be.” He stuck by the old Union of the Founders and entertained no thoughts of secession. As he said: “It is the principle I contend for. As an American citizen, I take great pride in my country, her prosperity and institutions, and would defend my state if her rights were invaded.” But then the events came very close to home. He was summoned to the Washington home of Francis P. Blair, a Washington, D.C. publicist and what looks to me to be a Republican party go-to man, where he was informed that President Lincoln was offering him [the position of] commander-in-chief of the Union army. The minutes of Lee’s rejection read thus: “If the Union is dissolved and the government disrupted, I shall return to my native state and share the miseries of my people and save in defense will draw my sword on none.” Can you imagine the temptation? If [Ulysses S.] Grant became President, there’s no doubt that that Lee would’ve been President. He would’ve moved from colonel to commander-in-chief at the snap of your fingers!

His dream of commanding the army that he loved would be his. He turned it down for this reason: “I cannot raise my sword against my own people.” As he writes to a friend: “I declined the offer he made to take command of the army that was to be brought into the field, stating as candidly and as courteously as I could, that though opposed to secession and deprecating war, I could take no part in the invasion of the Southern states.” Then the events got even closer when Lincoln prepared for an invasion of the South with 75,000 troops. And then Virginia seceded. Lee resigned his commission in the United States Army and returned to Arlington. Mrs. Lee writes this: “My husband has wept tears of blood over this terrible war, but as a man of honour, and a Virginian, he must follow the destiny of his state.”

To his sister, Lee wrote:

“I am grieved at my inability to see you. Now we are in a state of war, which will yield to nothing. The whole South is in a state of revolution into which Virginia, after a long struggle, has been drawn. And though I recognize no necessity for this state of things and would have forborne and pleaded to the end for a redress of grievances real or supposed. Yet,” (This is, this is key to what I want to say. This is gonna end up in Lee embodying the cause of the South). “Yet, in my own person, I had to meet the question, whether I should take part against my native state.”

He had to meet the issue of his principles in his own person, and there a transformation would take place. Obviously, these are very interesting responses and it’s fascinating to watch Lee’s mind work through these citations. Though Lincoln is prepared to invade and all the threats of the Federal government are coming to bear on the South, Lee will not say: “The Union now must be dissolved. Secession is now warranted.” No, he sticks to his principles. Though he remains for the Union, he declines to participate in the invasion of the South. Almost like a formula, he repeated over and over again when asked: “With all my devotion to the Union and the feeling of duty and loyalty of an American citizen, I have not been able to make my mind up to raise my sword against my relatives, my children, and my home.” He said that as if it was a pat answer that he had in his back pocket whenever anybody asked him so he wouldn’t have to go on and on at length about it.

Enter the revisionists stage left. Elizabeth Brown prior asks (and I really do think professor Pryor wants to be fair to Lee but she’s just perplexed what Lee is up to here): “Why, if he believed all he said he did, did he come to this point?” And as she continues: “His formulaic use of language gives an impression quite the opposite of the conclusion he should have reached.” What confuses modern historians, as Ms. Pryor expresses it, is that Lee: “had numerous options available to him if his beliefs on Union and secession were, in fact, sincere. For instance, General Winfield Scott was just as loyal a Virginian. He had never doubted that his path lay with the Union. He was insulted,” she reports, “that he would be expected to join a Confederacy. There were many others who took General Scott’s path,” she concludes. Gary Gallagher sees Lee’s decision as evidence that his loyalties, when push comes to shove, were changing. “Finally, when push comes to shove,” according to Dr. Gallagher, “Lee was finding that despite his words of loyalty to everything American, his heart really lay with slavery.” So, you see the transformation from his time to ours.

There are many ways to chart this, this is a really interesting way. You see, in the very latest book, this is one of Gallagher’s that just came out, [Lee’s] heart lay with slavery, secession, and the white South and the old Virginia aristocracy. Gallagher uses Lee as a model of the transformation of loyalty that led many Southerners to embrace the new Southern nation and abandon the old Union of the Founders. The book is called Becoming Confederates, and he sees this as a way in which once-loyal people transformed, using Lee and others in the book as a model, to show how loyalty to the Founders transformed into loyalty to slavery, aristocracy, and on and on. Dr. Gallagher is the leading modern proponent of the “Lost Cause School” and has written a big book on it several years ago. But note an important shift in the power of the new historians. Dr. Gallagher is trying to show, since Lee is making no pro-slavery statements before the War, the “Lost Cause” maneuver won’t work, he’s trying to show that statements of Lee’s before the War, which are very pro-union and anti-secession, can be interpreted as if by magic to explain what Lee did at the outset and during the War.

Here comes the “H-word,” this bipolar hermeneutic of suspicion. That’s a tag from the eighties. The French philosopher, Paul Ricœur, coined that phrase for people like Nietzsche, Marx, Freud, [and] others who [argue] “I know, despite what you’re telling me, I know what you’re really thinking,” [people] who are very suspicious of what you have to say. So, we move the suspicion from after the War, now to before the War. We’re just suspicious. It’s a bipolar hermeneutic of suspicion. Wouldn’t it make more sense to determine whether his [Lee’s] stated motives fit his actions as the fiercest warrior and brilliant general of the Southern cause? Wouldn’t your first move try to be [to figure out] why did he become what he became given what he said? Why try not to be suspicious, but try to follow the movement of his mind, which I’m asking you to do. I propose that this can easily be explained if we care to understand the reason the South really fought, and this will then lead us to see the reason Lee was not only revered in his time, but also embodied for many the Southern cause and all Southern hopes for an independent nation.

Let us take a page out of the political theory of Southern political theorist, John C. Calhoun. We’ve talked a lot about Calhoun. We haven’t pushed it as far as I’m gonna go right now, where I think we really get to the meat of what Calhoun is up to in his theory. In reasoning that all human societies require order (that’s a pretty normal thing to think), they require a power of governance over them. Calhoun did not think that government was a necessary evil. It was a positive part of living a social life. You need governance. He said it was given by God. There’s no avoiding it if you want to stay a coherent, historic people in time. But then Calhoun went a step further to say that for the very same reasons that society requires government, society must have a means of control over the government if the just order is to be maintained. He’s only stated one reason right now, and that’s the control of a network of people, be it society, or be it government. Because of the ever-present threat of disorder and anarchy, both society and government need constraints, not the same constraint, but some measure of control for the good of each. Calhoun reasoned thus: Government is to society as constitution is to government.

You see what he’s done is [say] that, as society needs to be constrained by government, so government needs to be constrained by constitution. I think we get the general meaning of the word constitution, even though he has a very precise and very technical use of the word, which I’m going to get at. His use of the word constitution is interesting. He means what we would expect in part, a written constitution (or an unwritten constitution for that matter), which forms and places controls on the government, but he also means something else, which is vital to understanding Calhoun, and I don’t think we’ve pushed this far with him. He means: “That association of individuals founded on the implied assent of all of its members which precedes all government.” He’s very clear. He says it’s a terrible mistake to think that by constitution, we mean the compact, which is what we would ordinarily think. He doesn’t think that. He thinks the association of individuals and the implied assent of a society, of all its members, which precedes all government and from which the government and the constitutional compact spring.

By “constitution” he does not mean simply “compact.” He means the assenting association. The way I learned to work with this term (and this doesn’t say it quite right), [is] that he’s talking about the constitution of the people as an assenting assembly before any compact is made itself. The constitution of a people, that is who want to make a compact for governance, and as both the origin and the purpose, both the origin and the purpose of government, it [the people] must remain the controlling agent. It must remain the controlling agent. The society, the assenting assembly, not government, but the assenting assembly, must remain the controlling agent. When Lee said, then, that he was for the principled of union, the system of American Federalism, but could not sacrifice his society, Virginia, his people and family, he was making the vital point Calhoun laboured to make throughout the 1820s, 1830s, and the 1840s. He [Lee] embodied it in the agony of turning down that offer, which he simply could not accept. He could not raise his sword against his people. So, there is a profound reason apart from what our revisionist historians are saying, that he finally caved in to white supremacy, slavery, Virginia aristocracy, all that.

What about voting? You have the power to vote. Suffrage is not enough. Voting simply puts a people in power, and it can transfer power from one group to the next, but is not in itself a check upon power as such. It simply transfers it. We go from the Republicans to the Democrats. We go from Bush to Obama. It just goes back and forth. What is more, a numerical majority, you know, 25 people on this side versus 10 people on this side, a numerical majority in and of itself is simply coercion upon the minority. In and of itself! Aristotle calls a numerical majority a “plural monarchy.” That’s in Book Five of Aristotle’s Politics. As Aristotle put it, the proper majority is always concurrent, a concurrent, a voice of the society and societal interests in compromise, in mutual agreement where no one interest is constantly slighted by the others. That’s the true majority, [a majority] of the interests of the assenting assembly, not simply all the wood-cutters against the fishermen. [In that case], the fishermen are gonna wane and diminish.

It seems to me, there’s no doubt that Calhoun is taking a page out of Aristotle’s Politics here, where Aristotle ingeniously (I mean, I’m amazed at this move), says that equality can mean both a numerical equality as well as a proportional equality. It means both. We don’t have to play with its meaning. As we move from numbers down to proportions, you know. It means the same thing. I’ll prove it to you. Let’s take one proportion of our culture: People who are old enough to vote. So, everybody 18 and over can vote, everybody under 18 can’t. Now, even though there’s no numerical equality there, people under 18 can’t vote, nobody’s going to accuse me of being unequal. I’m being absolutely equal. I would be proportionally unequal, if I said: “Okay, you three guys there, my buddies who are under 18, you can vote. The rest of you, tough luck. The rest of you under 18, you can’t do it.” Then I would be proportionally unequal.

The voting age used to be 21. There was a claim: “This is not fair. We have to fight in Vietnam. If you’re old enough to fight, you’re old enough to vote.” That was the claim, and it won. It was proportionally unequal. it was not fair to those who could be drafted at 18 and have to fight, but were not able to vote in the matter. And the voting age went from 21 down to 18. I watched that happen. That’s a perfect example of what he means. So, equality means both. And without both involved in the affairs of the polity, there is no justice. You cannot be for union and equality of independent parts and [be for] interests at the expense of any minority part. Lee could not be for the Union and take up his sword against Virginia. It wouldn’t have been possible. To be for the Union would be to be for his state to that proportion. And equality means both. He would have to forsake proportional equality for numerical [equality], but numerical [equality] alone is nothing but power. 41 to 22 is a score, not a judgment in and of itself. You have to have it, but if you have it alone, you’re subject to tyranny.

To put it another way to be for the union of states is to be for the right of secession as secession is the check on the balance of the equality of all. Calhoun seems to me to be dumbfounded to imagine that anybody could ever entertain a division of powers where there is no check upon the others. Would it make any sense to have a separation of powers in the Federal government if there’s no check, say of the judiciary upon the executive? If there’s no check, they’re really not separate. As we’re slowly beginning to find out the check really doesn’t work. It’s just in name only, it’s only written on paper. Let me read a passage of Calhoun. This is from his Fort Hill Address of 1831. Now, obviously, if Lee has the preamble [to the U.S. Constitution] wrong, he has not mastered Calhoun’s writings, but you can see the movement of his mind struggling to get there: “How can I be for union and turn my sword against my own people?” And that’s the dilemma that finally led him to do what was exactly his duty.

“Nearly half my life,” Calhoun writes in 1831, “has passed in the service of the Union and whatever public reputation I have acquired is indissolubly identified with it. To be too national has, indeed, been considered by many, even of my friends, to have been my greatest political fault. With these strong feelings of attachment, I have examined, with the utmost care, the bearing of the doctrine in question; and, so far from anarchical or revolutionary, I solemnly believe it to be the only solid foundation of our system, and of the Union itself; and that the opposite doctrine, which denies to the States the right of protecting their reserved powers, and which would vest in the General Government (it matters not through what department) the right of determining, exclusively and finally, the powers delegated to it, is incompatible with the sovereignty of the States, and of the Constitution itself, considered as the basis of a Federal Union. As strong as this language is, it is not stronger than that used by the illustrious Jefferson, who said, to give to the General Government the final and exclusive right to judge of its powers, is to make ‘its discretion and not the Constitution, the measure of its powers.’”

Now, let’s look at what Lee had to say after the war. He sounds exactly like Calhoun: “If the result of the war is to be considered as having decided that the union of states is inviolable and perpetual under the constitution, it is incompetent for the general government to impair its integrity by the exclusion of a state.” Yeah. If the numerical power has said that we are in a perpetual union, then it follows that it cannot impair the good of any one state. One says the other. “The exclusion of a state would be as unjust as for the states to do so by secession. The existence and rights of a state by the constitution are as indestructible as the union itself.” He’s got it nailed. He’s got exactly what Calhoun was writing thirty years before and throughout his life. Douglas Freeman sums it up well:

“As he fought for the Southern cause, however, he came to see its meaning. Sacrifice clarified it. One cannot say when or how, whether it was by his own reading or through the debates in winter quarters or from the contagion of political belief, but Lee absorbed the Southern constitutional agreement and was convinced by it. ‘All that the South has ever desired,” he wrote in January of 1866, “was that the Union as established by our forefathers should be preserved, and that the government as originally organized, should be administered in purity and in truth.’”

Throughout the aftermath of the war, he said over and over again: “If I were asked to do the same thing, I’d do the exact same thing.” It was the principle involved. “I would do the exact same thing.” And he saw how his duty and principle would meet as he faced the question of the injustice coming his way, initially in the 75,000 troops bearing down on his state. In James Robertson’s biography of Stonewall Jackson, you see what was happening in the Northern Shenandoah Valley, farms burning, homes being wrecked, animals slaughtered.

What is of interest here is that before the War, Lee embodied the thoughts in his action. We’ve heard over and over again that the shape of morality is seen in action. It is seen in his action, almost alone initially, were it not for the brief formula he gave about favoring the union, but would not raise his sword against his state. As he wrote to his sister in April, 1861 (which I quoted earlier), he had to confront the conflict in his own person. He embodied, he enacted, the Southern response to the conflict. In Robert E. Lee, duty and will remained one, were indeed one and the same, in his decision to turn down that amazing offer and take up for the South. As Freeman said at the outset, there is no mystery. His will was his duty and his duty was his will. The power of revisionist historiography has betrayed an unwillingness simply to confront, or perhaps an inability to understand, the Southern point of view. This could have easily been done. I’m not a political theorist and I’m not an historian, and I did it. But as the great Lee said, the dominant party cannot reign forever. Truth and justice will at last prevail. Thank you.

Is Wilson saying that Gallagher, and others, don’t understand how a principled mind works, like that of Lee, and therefore have to contrive some explanation that fits their limited grasp of duty and loyalty?

This is so good. Yes. Lee, pro-union, anti-war, anti-tyranny. Courageous, martial friend of the underdog when community is usurped by tyranny. It makes so much sense. How could he be for a “union” that was out to crush the places where the union was made *actual*. The eye cannot say to the hand, I have no need of thee (I just made that up) and be a real body. Much, much to think about here. Go, Bill.

I think he is, yes. I disagree with a lot of what Gallagher teaches.