Part 4 in Clyde Wilson’s series “African-American Slavery in Historical Perspective.” Read Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3.

Many Americans doubtless tend to assume a rosy view of emancipation, of brave boys in blue rushing into the arms of newly freed slaves to celebrate the day of Jubilee while handing out Hershey bars to children.

Nothing could be further from the truth. Emancipation and its immediate aftermath were not a positive experience for most African Americans.

In order to understand the wartime experience of African Americans you have to understand the war. The invasion of the South began officially as an effort to suppress the elected governments of the seceded States, under Lincoln’s phony theory that openly debated and democratically enacted secession was only the act of a conspiracy of lawbreakers.

This claim was made by a government that was legally pledged not to interfere with slavery. In early days Union soldiers acted to return runaways to their masters. The blacks who accumulated in Union hands in occupied Southern areas were referred to demeaningly as “contrabands.” Lincoln’s control of the government required pacifying the Border States, where many large slave-owners were Unionists. The Border States and the rich area of southern Louisiana where Northern interests were already exploiting confiscated property were exempted from the Emancipation Proclamation.

In due time Confiscation Acts were passed seizing the property of “rebels,” including “contrabands.” This careless no-policy was designed to punish recalcitrant Southerners and showed no awareness of or real interest in the status or needs of the African American population of the South. The Russian Czar, who had recently presided over a planned emancipation of serfs and was Lincoln’s only European sympathiser, condemned the Emancipation Proclamation for this.

The war from the beginning became a war against civilians—terrorising noncombatants, black and white, and destroying and stealing private property as a routine matter. Of course, this accomplished nothing except to stiffen Southern resistance. Republicans had to wage war not against evil “traitors” but against a whole people determined to resist. This total war procedure intensified as the war went on but was in effect from the first day.

Many Americans tend to think of themselves as very nice people dedicated to doing good in the world, a sentimental self-serving delusion that has led to major catastrophes such as failed foreign wars to spread “global democracy.” This niceness was certainly not on display in their invasion and conquest of fellow Americans of the South. The devastation inflicted on the South by the Union Army, leading to long-term impoverishment of black and white, would justify reparations for such large scale atrocities against Americans. But that would require accepting an honest rather than a self-righteous view of U.S. behaviour.

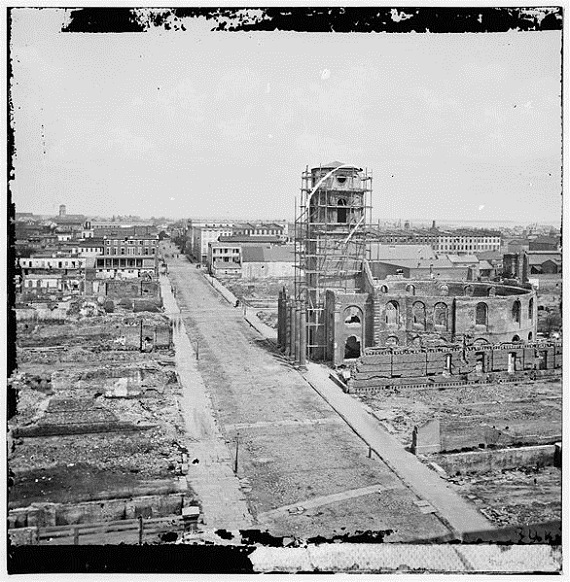

Nobody who knows the facts about the Union army’s treatment of noncombatants, including African Americans, destruction of private property, and the graft and corruption that went with it, can possibly entertain any righteousness about it all. The unprecedented massive bombardment by the newest heavy weapons of cities full of women and children, as at Charleston, Vicksburg, and Atlanta, did not spare African Americans.

How little impact the reality has made on American consciousness. One celebrity “historian” relates how Sherman’s 60,000 brave, clean-living, and democratic citizen soldiers marched through the South hardly harming anybody. Such statements would be laughable if they were not so malicious and destructive of truth. In fact, you can prove the horrors of Sherman’s March, and many other such events, entirely from Northern sources without citing a single Southern testimony. And, in simple fact, Sherman’s march was not a fighting action but a deliberately designed attack on Southern civilian infrastructure and morale. Sherman himself said that he destroyed $2,000,000 in property and would be tried as a war criminal if he lost.

The accompaniment to this fake history: I recently encountered a movie in which Confederate soldiers rode into a town, shot women and children in the back, and burned up people in a church. I understand there is a popular tale going around about Confederate soldiers bashing black babies against trees.

Such things are obviously constructed from hatred and are designed to foster hatred. No motive is ever given for such behaviour, the explanation apparently being that Southern white people are innately vile.

There is no record of any such behaviour by Confederates but plenty of Southern women suffered destruction of homes and possessions, guns held to their heads, and valuable earrings ripped off. Torturing people, black and white, to reveal the whereabouts of valuables was routine, and burning of schools, churches, and even a convent, were frequent practices. There was no killing of children unless you count resistant 14 and 15-year-old boys and those who perished from homelessness and malnutrition.

Compare Quantrill’s raid on the town of Lawrence, Kansas. Lawrence was not a sleepy, innocent town. It was an armed camp and the headquarters of Republican forces that had for years inflicted merciless havoc on Missouri civilians. In this raid not a single woman was harmed. Even so, the action was disapproved by the Confederate government. Lincoln rewarded and promoted generals for their unmilitary destructiveness.

I met a fellow who said he hated Confederates because “they invaded my country,” and I understand that Civil War memorials in Pennsylvania are being altered to emphasise Confederate “invaders.” Setting aside the question of whose country it is, Confederates are now the invaders because of one orderly foray into the North, which was partly designed to give relief to the civilians of Virginia.

This description of a time when the U.S. government had organized the largest armies ever seen on the North American continent in multiple destructive invasions of the South.

The encounter of Union soldiers with the black people of the South was frequently not agreeable on either side. Many Union soldiers, the one-fourth of them who were foreigners and others, had no familiarity with Africans and regarded them with extreme distaste, finding them alien and repulsive. Their letters are full of racist observations that would gladden the heart of Joseph Goebbels. Without doubt African Americans suffered an immense amount of abuse from Northern soldiers, probably more than the whites because they had less leverage to protest.

Of course, there is certainly now waiting in the wings a young upward bound historian who will claim as a fact that the suffering of African Americans in the war was due to the violence and oppression of white Southerners. Not true. Fighting desperately, Confederates had no reason to abuse their labour.

Consider: When an invading army burns houses and barns and fences and farm equipment and wantonly kills or steals livestock, standing crops, food from the cellar, corncrib, and smokehouse, the bonded people as well as the whites are left homeless and hungry, sometimes needing to take to the road to hunt for subsistence. Northern soldiers were surprised that many slaves had watches, fine clothes, and savings never seen in their own slum neighbourhoods and had no hesitation in taking them on the false excuse that blacks could not own property in the South.

Of the nearly 3 million men who served in the Union army at some point and who received pensions that were the biggest item in the federal budget for years, more were involved in occupying and preying on Southern civilians than ever saw combat with armed enemies. The celebrity historian previously mentioned, V.D. Hanson, portrays Union men as the great example of democratic citizen soldiers. There were many good men in the Northern army, but its overall personnel was mercenary—hired with bounties equal to three years of a worker’s pay or just off the boat. It is the Confederate army that provides an example of the true citizen soldier.

As has been documented, one result of this lack of concern for the welfare and fate of black Southerners was the Union army gathering homeless black people in concentration camps which proved to be pits of disease and hunger. In general, the U.S. Army thought of blacks as either potential labour or nuisances. Sherman more than once expressed impatience with the complications caused by homeless black people.

Ambrose Bierce, a hard-fighting Union soldier throughout the war, said the only blacks he saw were the servants and concubines of Union officers. Many Union officers regarded black people as fit only for such purposes. Adapting to local custom, Union officers set up their own New Orleans quadroon and octoroon brothels. Some Yankee soldiers wrote home boasting how their life had improved since acquiring a personal servant.

Many African Americans took to the roads not seeking an intangible emancipation but because their homes and means of living had been destroyed. Much is made these days of slaves escaping to Union lines seeking freedom and enlisting in the Northern Army. In fact, it is not at all clear what percentage of black people liberated themselves and left of their own will and what percentage were literally forced away from home. We will never know for certain. A Northern observer of the U.S. army in occupied coastal Carolina wrote that the generals declared their intention to recruit “every able-bodied male in the department.” He added: “The atrocious impressment of boys of fourteen and responsible men with large dependent families, and the shooting down of negroes who resisted, were common occurrences.”

Many African Americans left devastated homes and took to the roads seeking subsistence or to test their freedom of movement. They ended up in unhealthy camps from which they were used as labour or cannon fodder. Sudden liberty could be a scary and puzzling as well as a liberating experience. William Faulkner captures this brilliantly in The Unvanquished. The black men recruited for the army or labour had to leave their helpless wives and children in the high-mortality and underfed concentration camps. And some who left plantations on their own left children and old people to be tended by the whites.

The more enlightened Northerners thought blacks should be offered the opportunity to prove themselves as soldiers, having the right to be worked for less or no pay and be sacrificed in forlorn hopes as at Fort Wagner and the Crater. And helping to keep so many Massachusetts men safely at home.

It is now proclaimed that the slaves themselves secured their freedom. It is comforting to believe heroic stories about one’s ancestors in the age of Wakanda, but this is a dubious claim. Yankees always hoped for bloody revolts (one of the motives of the Emancipation Proclamation) and work stoppages. These never happened except as scattered local incidents. African American labour remained a mainstay of the Southern effort almost to the end. As hard as it is for people today to believe, except where the Northern army ravaged the population, most of the black people remained at home and continued their lives as before.

The lack of any considerable slave uprising during the war becomes even more salient when we realise that the African American population was the majority in a large swath of the Confederacy from Southside Virginia to East Texas.

At the Hampton Roads peace conference a few months before Appomattox, Lincoln suggested to the Confederate representatives that if they ceased fighting, emancipation could be left to the courts to rule up or down. Confederate Vice President Alexander Stephens, who unlike Lincoln cared about the fate of the black people, asked Lincoln what would happen to them when abruptly freed in their present condition. Lincoln answered with a line from a minstrel show, “Root, hog, or die.” His policy would become fact.

As Frederick Douglass, the foremost African American spokesman of the 19th century, was later to say, everything Lincoln did was for white people. Any benefit to black people was incidental. He acknowledged twenty-five years after the War that blacks were worse off than under slavery and that the fault was mainly with the central government in relation to which the black man is “a deserted, a defrauded, a swindled, and an outcast man—in law free, in fact a slave. I here and now denounce his so-called emancipation as a stupendous fraud—a fraud upon him, a fraud upon the world.”

Many black men served with the Confederate Army loyally and in various capacities. A thousand or more black men went with Lee’s army to Pennsylvania— and back. Black faces were noticeable in Confederate lines and camps and Yankees often complained of black men firing at them. Black servants often went freely on errands between the army and the homeplace. President Davis when he visited army camps shook hands with black men and white. The Brit observer Colonel Fremantle saw a black Confederate marching a Yankee prisoner to the rear at Gettysburg. He wondered what the London abolitionists would make of that.

Bedford Forrest’s elite headquarters company contained several black men. Forrest took 30 of his men with him to the war, promising freedom if they served faithfully. All but one did. Black Confederates were welcomed at veterans’ reunions and received pensions from Southern States.

In many cases African American Southerners regarded the invaders as criminals, tried to protect their white folks, and often suffered severe consequences. Torturing black men to divulge where valuables, food, or horses were hidden was routine practice.

To any intelligent honest person, none of this should be surprising. History is full of examples of servants siding with their masters against enemies. Plantations outside the war zones continued to operate. The greater number of black people remained at home.

It is very likely that most slaves did not have their freedom announced by the boys in blue. Often freedom was announced by their former master just returned from the Confederate army—ragged, destitute of money, and often disabled. He assembled the people and told them they were free. They could go whenever and wherever they wished. If they stayed, they would all try to work together to plow and plant and survive.

The truth can never be escaped that emancipation is inextricably linked with a brutal war of invasion and conquest. Emancipation was achieved as a cynical and opportunistic by-product of other goals, leaving its beneficiaries in a deplorable state.

The best evidence we have from the slaves themselves is contained in the Library of Congress’s multi-volume Slave Narratives: A Folk History of American Slavery. The narratives contain over 2,300 interviews with surviving slaves made 1936-1938 . These materials have been criticized in various ways, but they cover every State and are fairly consistent in what they tell. Some terrible stories are told, but in general the narratives show no great resentment against slavery and masters, and many complain of the decline in the living standards after emancipation.

Here are a few samples of testimony from Paul C. Graham’s book When the Yankees Come. All relate to North Carolina where invasion and occupation was thought to be milder and shorter:

“My mother had bought a pair of shoes and put them in a chest. A Yankee came and wore the shoes and took them off, leaving his in their place. They told us we were free.”

“When we heard the soldiers coming the boys turned the horses loose in the woods. The Yankees said they had to have them and would burn the house down if we didn’t get them. So our boys whistled up the horses and the Yankees carried them all off.”

“Some of the colored folks followed the Yankees away. Five or six of our boys went. Two of them travelled as far as Yadkinville and come back. The rest of them kept going and we never heard tell of them again.”

“They did kill all of the things they could eat and they stole the rest of the feedstuff. They make one nigger boy draw water for their horses day and night.”

[When the Yankees come through:] “Well, we all went away. That winter was tough. All the niggers near about starved to death. . . . After a while we had to go to our old masters and ask them for bread to keep us alive.”

“The Yankees, when they took us. . . . made us steal and take things for them. . . . We went to one place and the white woman only had one piece of meat and a big gang of little children. I begged the Yankees to let that piece of meat alone, she was so poor, and the officer told them to take it, and they took her last piece of meat.”

“I ain’t seen no happy niggers since them fool Yankees come along.”

“They came to our house and took our something to eat. Yes sir, they took our something to eat from us Negroes.”

“The Yankees done a lot of mischief. I knows because I was there. They robbed the folks and a whole lot of darkies who ain’t never been whipped by the master got a whipping from the Yankees.”

[Went with the Yankees and stayed four months:] “They gave me clothes and shoes but I slipped away from them because they wanted me to do things I didn’t want to do [steal].”

“The Smith house was a hospital. They came into the house, my sister Irene was a house girl. They put their pistols to her head and said, ‘You better tell me where them things are hid. Tell us where the money and silver is hid at.’ . . . They took my mother’s shawl and a lot of things belonging to the slaves.”

“The Yankees took the best of everything. . .They even buyed tobacco from my mammy. . . .They paid her with shin plasters.”

“I was just five years old when the Yankees come. . . . I does remember that they herded us together and make us sing a heap of songs and dance. . . . One black boy won’t dance he says, so they puts him barefooted on a hot piece of tin and believe me he did dance.”

“I remember how some of them Yankee officers cussed in front of my missus and how I told them that they might be Yankees but they worn’t half raised at that.”

“My uncle, Parker Pool, told me the Yankees made a slave of him. His master was good to him. He was as happy as he could be before the Yankees come. . . . Yes, the Yankees freed us but they left us nothing to live on. They gave us freedom but took most everything and left us nothing to eat, nothing to live on.”

The Great Lie that Lincoln was a hero with Simon Pure character will never be destroyed. Unfortunately.

Deo Vindice