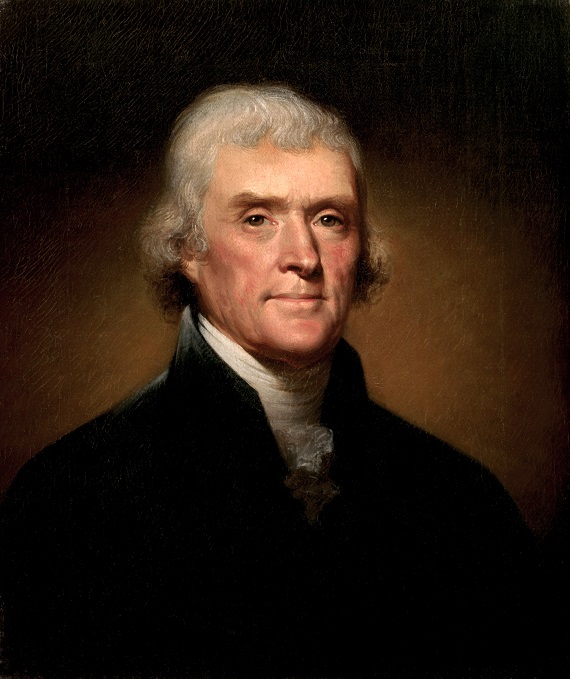

Aberrant as it has become, when the young Thomas Jefferson spoke or wrote of what he termed, “my country,” he was not referring to the empire of England or what became the United States of America. He was referencing his native State of Virginia.

Sixteen years ago, at the suggestion of Clyde Wilson in his book From Union to Empire: Essays in the Jeffersonian Tradition (2003), I purchased and began reading the six-volume biography of Jefferson by Dumas Malone. It was fascinating and enriching.

I recently decided to begin a second round. The first book is entitled Jefferson the Virginian.

The author was born in 1892 in Coldwater, Mississippi, to a Methodist minister father and a schoolteacher mother. He was raised in Georgia after his father was called to a rural church there. Malone enlisted as a Marine during World War One and later became a history teacher at the University of Virginia, where he became intimately familiar with the legacy of its founder, Mr. Jefferson.

The publishing scan for this work was 1948-1981. Originally planned to be a four-volume work, using as a model Douglas Southall Freeman’s renowned biography of Robert E. Lee, it grew to five, then six volumes. The first covers the years 1743-1784, roughly the first half of Jefferson’s life.

A child of the American frontier, Jefferson was born in Virginia into a life of wealth and privilege. Ironically, as a statesman, he would go on to become hostile to hereditary privilege and an advocate of meritocracy and the common man. He was educated at the College of William and Mary where he developed a highly disciplined life, including a daily schedule of activity which allowed time for networking with luminaries at the State capitol, then located in Williamsburg. It was here he began a long and often contentious relationship with Patrick Henry. These two Virginians would figure prominently in the struggle for independence to come, Henry being the mouthpiece of revolution and Jefferson its pen.

After college, Jefferson studied and practiced law prior to entering public service. But he never ceased expanding his mind. His scholarly pursuits led him to be a firm believer in the power of knowledge and a proponent of liberated intelligence.

In May of 1769 he was elected to his State’s House of Burgesses and took his seat for the first time as a member of a legislative body. From there he set off on a road to distinction.

Covering domestic life, Malone devotes a chapter to the genesis of Jefferson’s “Little Mountain” of Monticello. He married Martha Wayles Skelton on New Year’s Day 1772. They had six children in ten years, but only two that survived to maturity. Exhausted and afflicted with health issues, Martha died tragically in 1782 soon after giving birth to their last child. Jefferson never married again.

Jefferson was an intensely private man when it came to his family and his religious beliefs and remained so throughout his life. His letters exchanged with his wife were burned after her death; his written entries in his personal ledgers about the deaths of his children are brief and largely emotionless.

It was as a young man Jefferson committed an indiscretion with a good friend’s wife that led to a multitude of lewd allegations that his political opponents would make use of for decades to come. Malone devotes an appendix to “The Walker Affair.” Two hundred years before Anita Hill, Betsey Walker waited sixteen years after the episode, when Jefferson had already departed for a mission in France, to divulge to her husband her “relationship” with Jefferson, which she claimed had continued for years.

These (and other) unsavory allegations from his enemies hounded Jefferson. Included is the now widely believed story of his fathering children with slave Sally Hemmings, which has never been proven true. During an early round of these rumors in 1805, he determined to his friends “to stand with them on the ground of truth… You will perceive that I plead guilty to one of their charges, that when young and single I offered love to a handsome lady [Betsey Walker]. I acknowledge its incorrectness. It is the only one founded in truth among all their allegations against me.”

Meanwhile, as a patriot Jefferson evolved into a committed republican, resolving to stand with Massachusetts in her defiance of British tyranny. He denied first the authority of Parliament, and then of the king himself, coupling his newfound nationalism with his loyalty to Virginia and becoming what Malone dubbed “an open secessionist.”

In March 1775 Virginia burgesses held a State convention in Richmond and purposely neglected to invite the royal governor. It was here where Patrick Henry declared, “Give me liberty, or give me death.” Lexington and Concord had yet to occur, but Henry believed war inevitable unless the colonists should become abject. “Let it come,” he said. Jefferson strongly supported Henry’s resolutions.

Shortly after, Jefferson was elected to serve in the Continental Congress in Philadelphia, where the subject of independence was to be acted upon in earnest. Bound in honor, crossing the Potomac was crossing his Rubicon, for there was no turning back. Patriots and statesmen to their countrymen, Jefferson and his colleagues were rogues and outlaws to the British empire. George III had declared the colonies in a state of rebellion and threatened dire punishment to traitors.

Aroused to passion, Jefferson proclaimed, “…by the God that made me, I will cease to exist before I yield to a connection on such terms as the British Parliament propose; and in this, I think I speak the sentiments of America.”

The ties that bind were broken.

In Philadelphia, Jefferson would begin a long friendship with John Adams and have his Declaration of Independence watered down by the likes of John Dickinson and Benjamin Franklin. Jefferson was never a military man and had little involvement in those affairs. His was the art of “psychological warfare.”

Following his service in the North, Jefferson turned his attention to helping craft a constitution for his commonwealth of Virginia. He was actively fighting to leave Congress to tend to what he considered this more important business. He also turned down a mission to France to become a Virginia legislator, where as a republican reformer he strove against aristocracy and was an architect of laws concerning slavery and crime and punishment. He rejected the institution of slavery while strongly favoring colonization due to the incompatibility of the two races. And he authored a religious liberty statute that became one of his proudest personal achievements.

Jefferson was elected chief executive of his State on June 1, 1779, and embarked on a troubled two-year stint as a war governor. With inept executive power that would not be rectified until after he left office, Jefferson refused advice to operate outside the bounds of the law. He dealt with currency problems; a virtually non-existent navy; the limitations of militia; a want of manufacturing, crops, and arms; battlefield distresses and being caught off guard by an invasion led by Benedict Arnold; and a fleeing government.

British soldiers descended upon Monticello. Governor Jefferson did not leave the property until practically every other person was gone and the enemy approaching. Even though the entire State government was on the run, only his actions were subsequently the issue of a government inquiry which ended in a unanimous vote of exoneration from the Virginia Assembly. Nevertheless, the false charges of exhibiting “cowardice” at this time would also be hurled by those same bitter enemies for decades into the future in the environment of extreme partisanship of the late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries.

Jefferson the Virginian ends with him returning to the Continental Congress before finally accepting a mission to France, where he would be when the Constitutional Convention would meet back home and draft that document, which he thought did not go far enough in safeguarding the liberties of the States and their people.

Among the reflections induced from this fine work of historical biography is the absolute derangement of our current, self-absorbed, ignorant, Post-Marxist Left, who have the gall to be dismissive about the founding generation. One could pool a convention hall of “1619 Project” participants and not have the decency, decorum, respect, and intelligence of one of the least of these gentlemen.

For Jefferson himself, he never lost the import he put on being a Virginian and a Southerner. He did suffer the consequences of being a child of the Enlightenment, but he struggled to maintain consistency of thought, even when it cost him dearly, as during his tenure as governor. He had an unusual and unwarranted optimism about people in general and the cause and progress of the war for independence (he continued to be desultory about British encroachments into Virginia while pushing fanciful concepts of American invasions into Canada).

However, his inspiration and leadership in unifying the colonies in asserting their rights, pushing for secession and independence for his own and sister States, and his primary role in drafting the Declaration of Independence are worthy of our gratitude and admiration today. The pen was a mighty weapon in our first war of independence, and no one wielded it more courageously or effectively as Mr. Jefferson.