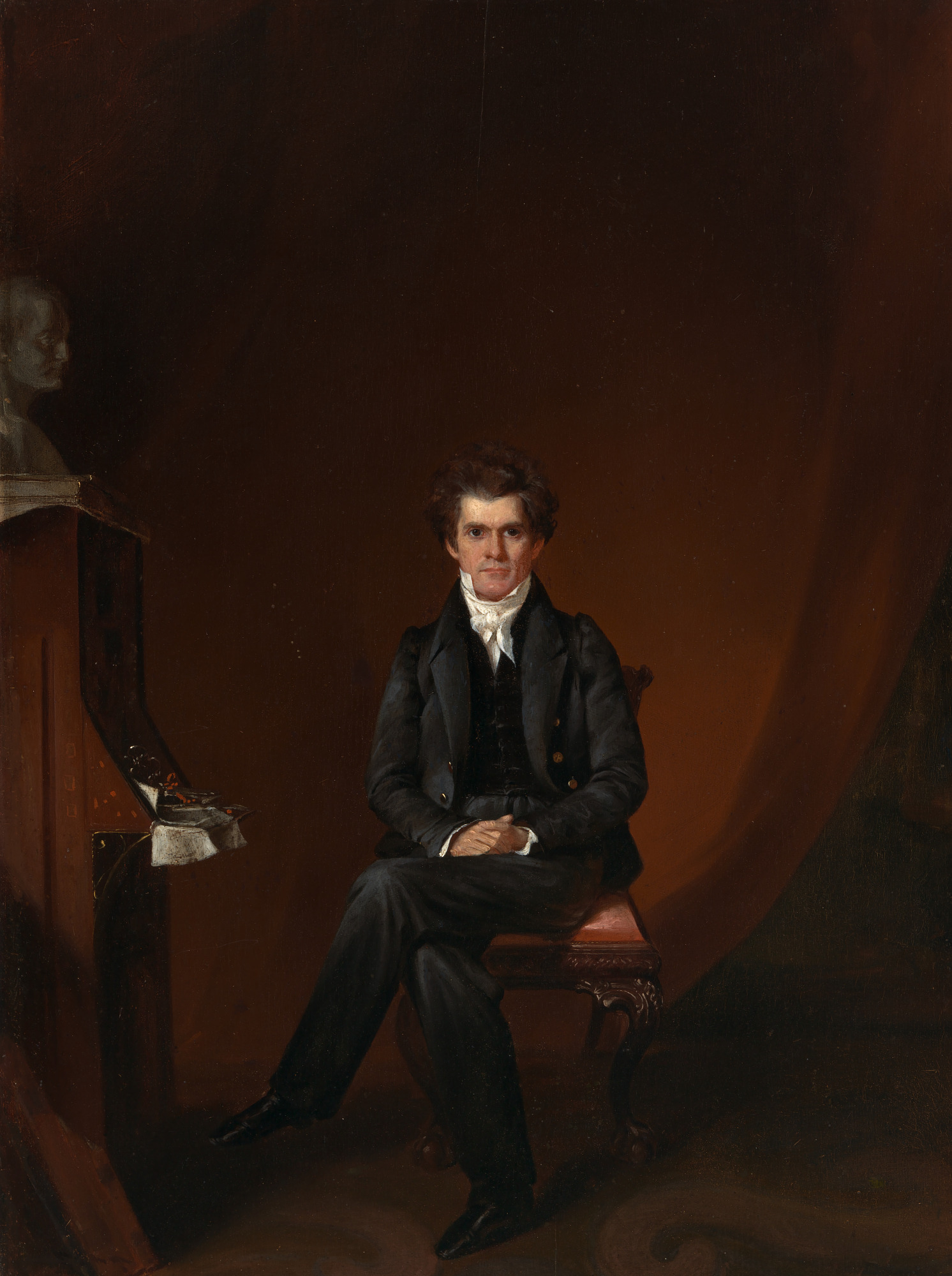

From Gustavus Pinckney, Life of John C. Calhoun.

The attentive reader will not have forgotten that in the letter of Mr. Calhoun in reference to his acceptance of the Secretaryship of State he made mention of a project which he had in mind for leisure hours in the home routine to which at that time he looked forward. The home routine, as has been seen, was sadly broken up. In a letter written in 1847 he says: “But it seems to me the more I do, the more I am compelled to do, and the farther I recede from retirement.” Of leisure also, it may readily be gathered, there was scant measure granted him. But the project, in spite of official duties, social engagements, burden of responsibilities, and ill health, was executed. There is much in all this to show how near this project was to his heart. There are not wanting other side lights to illustrate the same fact. In the discriminating remarks above quoted, Mr. Venable does not fail, in describing Mr. Calhoun’s last days, to lay particular emphasis on the concern shown by him in reference to the completion of this work. “His richest legacy to posterity,” are Mr. Venable’s words. During his latter years, Mr. Calhoun constantly refers to the progress of this work in his letters to his daughter, Mrs. Clemson, which is strong evidence of the interest he felt in it. The very last letter written to her, only a month before his death, contains the following passage: “Besides my correspondence, which, with Mr. Clemson, extends, when from home, to nine persons in my own family, and when at home, usually five or six. I have written between three hundred and fifty and four hundred pages of foolscap, in execution of the work I have on hand, since we parted, and have reviewed, corrected and had copied the elementary disquisition on government (now ready for the press), containing one hundred and twenty-five pages of foolscap. When I add that I have done all this in the midst of a round of company, and my many other engagements, I think you will see that I have a very good excuse if I have not written you as frequently as formerly.

The intention to prepare such a work doubtless lay half expressed in Mr. Calhoun’s mind a long time. The first reference to it which has been found in his correspondence occurs in a letter to Francis Wharton, written Christmas day, 1843: “The conception on that side of the Atlantic is universally false in reference to our system of government. It is indeed a most remarkable system—the most so that ever existed. I have never yet discussed it in its higher elementary principles, or rather, I ought to say, in reference to higher elementary principles of political science. If I should have leisure, I may yet do it.” Thus almost seven years elapsed from the first mention to the completion.

It seems certain that Mr. Calhoun realized thoroughly that what we now know has occurred would occur. Plainly he saw that the times immediately succeeding him would be clouded by passion, violence, and ignorance. Not until these had run their course would receptive ground be found for the seeds of wisdom which he knew it had been given to him to sow.

All too well he knew that, plainly, explicitly, unmistakably, as he had declared his discoveries, the record by passion and slander would be distorted past recognition. Besides, the principles as declared by him during his political career were more or less intermingled with the current questions and local issues, hence all the more apt to be confused and sunk from sight. Thus, the true ultimate issue in Nullification was connected with the tariff, an involved and troublesome dispute in itself. The popular imagination, moreover, is ever prone to make matters personal. Thus there has been a tendency, not only among the illiterate, to make of Nullification a mere personal matter between Jackson and Calhoun. As was early remarked in these pages, it seems strange that any historian, with the precedent of Nullification before him, could fail to understand the true nature of the Civil War. The parallelism is perfect. Tariff in the Nullification crisis is the exact analogue of slavery in the Civil War. Mr. Alexander H. Stevens has given a complete and perfect exposition of this matter, in spite of which many continue to misunderstand.

That all this misunderstanding, all this confusion of matter universally important with matter strictly local and temporary would prevail for many a year was precisely the state of affairs to which Mr. Calhoun looked forward, and against which he was anxious to provide every corrective in his power. striking to observe, throughout the utterances of his riper years, an entire consciousness on his part that he would neither be heeded immediately nor understood. It is almost as though he were constantly addressing an audience hidden far away in the future, the hearers in his immediate presence being to all intents and purposes stone deaf. He well knew how truth has to fight its way.

To provide a brief and serviceable summary of his discoveries and their application was the object he had in view. Consequently, in this volume is contained the distilled essence of the long results of a lifetime. All heterogeneous matter, all complicating detail, every irrelevance, all surplusage, is pruned away and eliminated, and the result is a handbook of political science, as remarkable for completeness as it is for brevity. Indeed, brevity is the difficulty at the same time that it is the merit of such a work. One who has given but indifferent attention to these subjects is wholly unprepared to derive the full benefit of what is here compressed into such narrow compass. Moreover, the minds of many, in reference to these topics, are in much less favorable condition than mere passivity; the minds of many are completely possessed by certain prejudices and misconceptions, which render the successful inoculation of correct ideas almost hopeless.

There were two matters in particular which Mr. Calhoun was desirous of explaining so that no one who chose honestly to investigate could fail to understand. One was heretofore indicated in the study of Nullification. Suffrage is not sufficient to guarantee liberty: not only is not sufficient, but with suffrage alone, misgovernment, tyranny, and oppression, will continue almost to the same extent as without it. In addition to suffrage, the weapon of nullification, check, veto, interposition, must be somehow placed in the hands of minorities, or constituent interests. This is the first point. To its elucidation is devoted the first part of the work, “The Disquisition on Government.’

The other matter almost universally misunderstood is the fact that such a provision is actually a feature of the American Constitution. By an almost universal misconception the fact is not only overlooked, but an active and pernicious error usurps its place. The provision was incorporated in the American Constitution more by chance than from forethought. It arose from the fortuitous juxtaposition of separate local sovereignties. This essential feature, thus provided by chance, unless demonstrated with the utmost lucidity and insisted on with the utmost rigidity, is lost to sight, and error in this respect is wholly fatal. There is no halfway ground.’ Right understanding means permanence, stability, success. Wrong understanding means violence, revolution, failure. The American Constitution, rightly understood and construed, contains the necessary conservative principle; but under the largely predominating view, this principle is worse than lost; a conflicting, subversive principle is substituted in its place. To this end the second portion of the work is devoted, “The Treatise on the United States Constitution.”

Is it not plain what a great stake is here to be lost or won? This it is that so aroused Carolina and Calhoun in the days of Nullification. This it is that Calhoun, in the years of his ripe wisdom, felt the world to stand in need of comprehending. Here is the explanation why this project was so near to his heart, and why, in the face of all interruptions and difficulties, he drove it through to completion.

To the words which a man pronounces in his last moments, the law, as well as the world at large, is accustomed to attach peculiar importance. Here is the legacy of one of the wisest men that ever lived, framed at a time when, had he been the most unprincipled adventurer, interest, prejudice, or any kindred motive, could have had not the least influence. When a man like Calhoun compresses his last breath into words of advice, the world will be the sufferer if the advice remains unheeded.

There are not wanting other circumstances to lend a peculiar sanction to this work. The foregoing pages have been put together to very little purpose if it does not appear from the most casual inspection that Mr. Calhoun’s career was, to an extent wholly extraordinary, political. His education was scarce completed when he was plunged into political affairs. America, of all the countries since the world began, has been preeminently the pioneer in political science and political experiment. South Carolina, of all American States, from taste and inclination, as well as by reason of isolation and unique conditions, has been the very hotbed of political disputation and investigation. The period of Calhoun’s life was a period of peculiar agitation and upheaval. And finally he, of all South Carolinians, by education and intellectual capacity, was the best fitted to digest the political pabulum thus afforded. A specialist attains to knowledge undreamt of by the general practitioner. To a remarkable extent circumstances conspired to render Mr. Calhoun a specialist in political science. It is no wonder, then, that he should have attained to knowledge entirely too advanced for his contemporaries, entirely too advanced for several succeeding generations. The general public (to recur to the allusion of Mr. Venable) has not yet caught up with Bacon (witness patent medicines), and Bacon wrote some time before Calhoun.

It is remarkable how backward even the most cultivated and best informed foreigners are found to be in the knowledge of our institutions and of political science in general. Jefferson remarked this long ago.

It seems difficult, almost impossible, for them to comprehend our federal system. Mr. Bryce, in explaining the Constitution, as was before remarked, hits every part of the target but the bull’s eye. He was warm, as the children say, in hide and seek, for he does not fail to lay emphasis on the prominence in the system of the State governments, yet he fails to find the essential central truth.

“E pure muove,” said Galileo when retiring from the council of adverse sages. The sages were doubtless learned, eminent, respectable; but Galileo saw, they did not see. The inertia of society is immense. Moreover, quacks and charlatans abound. A justifiable conservatism thus enlists itself on the side of inertia, and the result is that granite mountains (thanks to dynamite) are less impenetrable than human heads. O! for some philosophic analogue of dynamite! With the aid of such it were possible, perhaps, to procure, even for new ideas, entrance and lodgment in their proper nidus.

In the speech on Oregon, Mr. Calhoun leaves on record an eloquent appeal to the two great Anglo-Saxon nations. Progress in peace, commerce, civilization, liberty, is the burden of that appeal. But of far wider application and far greater moment is this later appeal. It is an appeal not to one, nor to two nations: it is a precious message to all mankind. The American people, in part by chance, in part by patriotic endeavor, stumbled on one of the latest lessons of liberty. Jefferson in part profited by the opportunity, forecast and hinted at the policies so inculcated. Madison likewise, in part, profited by the opportunity. But it was left to Calhoun to receive the fading torch, to replenish its flame, and cherish it to fresh, glowing intensity, and set it up in a high place, to brighten all the future generations.

It is a grave and unusual responsibility to be charged with the delivery of a message to mankind. Calhoun did not shirk the responsibility; he appreciated it, assumed it, and, to the best of his ability, discharged it.

From A DISQUISITION ON GOVERNMENT:

“The necessary result, then, of the unequal fiscal action of the government is, to divide the community into two great classes; one consisting of those who, in reality, pay the taxes, and, of course, bear the exclusively the burthen of supporting the government; and the other, of those who are the recipients of their proceeds, through disbursements, and who are, in fact, supported by the government; or, in fewer words, to divide into tax-payers and tax-consumers.”

That sentence contains just about everything one needs to know about government in America, as truly in 2022 as the day it was written. Or more so.