Because the ethnic diversity of the Confederate Army is not appreciated by many historians, Jason Boshers, the commander-in-chief of the Sons of Confederate Veterans, and J. Brian McClure, the commander of the Louisiana Division of the SCV, declared September “Confederate Hispanic Heritage Month.”

The ethnically diverse Confederate Army included Irish dock workers in the Louisiana Tigers, the German Fusiliers who defended Charleston, men of Mexican descent who rode with the victorious Texas cavalry in the Red River Campaign, Native Americans who fought beside Richard M. Gano and Stand Waite, the only Indian to become a general officer during the Civil War, and African American Confederates who served everywhere. One example of the ethnically diverse nature of the Rebel army is Ambrosio Jose Gonzales, who was born in Matanzas, Cuba, in 1818.[1]

When he was nine, Gonzales’s father sent him to New York to be educated. One of his classmates was G. T. Beauregard, who became a lifelong friend. After four or five years, Gonzales returned to Cuba and finished his education at the University of Havana, where he took a law degree. Young Gonzales, however, decided to pursue a career in education. He was a professor of languages at the University of Havana in 1848 when he decided to join a group of Cuban Revolutionaries. A. J. (as he was called) became the rebels’ de facto ambassador to the United States, where he met with General William J. Worth, President James K. Polk, Secretary of the Navy John Y. Mason, and Secretary of the Treasury Robert J. Walker. There was serious talk about annexing the island to the United States—especially in the South, whose leaders wanted more slave state senators in Congress.

The Junta declared Cuba independent in 1849. They adopted a flag that is now the national flag of Cuba. When the Spanish government learned what was happening, they sentenced Gonzales to death in absencia. The rebels (i.e., the Junta), however, promoted Gonzales to general, chief of staff, and second-in-command to their leader, General Narciso Lopez. In New Orleans and Louisville, they raised a regiment of 500 men, most of whom were people of means, and sailed for Cuba.

The Junta forces (filibusterers) landed at Cardanas, which fell quickly. Unloading took too long, however, and the Spanish Army retook Cardanas in heavy fighting but not before General Gonzales was shot twice. Taken aboard the ship Creole, Gonzales had not recovered when a Spanish counteroffensive forced the survivors to re-embark. The Creole escaped the Spanish Navy and docked in Key West, Florida. Gonzales was taken to the home of Stephen R. Mallory, who also commanded the local militia.[2] When a Spanish warship approached and demanded that the rebels be turned over to them, a confrontation resulted. The Spanish, not wishing to risk a war with the United States, withdrew, but Gonzales was still not out of danger.

After he recovered, General Gonzales was arrested for violation of the neutrality laws and ordered to report to Federal authorities in New Orleans, which he did. He was indicted, along with General Lopez, Mississippi Governor (and former general) John A. Quitman, and an impressive list of American dignitaries who supported the Revolution. After two mistrials, Gonzales was released. He remained in the United States, became an American citizen, and married Harriett Elliott, the youngest daughter of a rich South Carolina planter, in 1856.[3] They had six children by the time she died in 1869.[4]

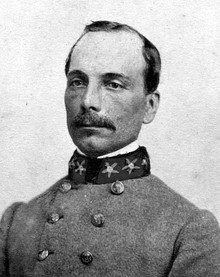

When the South seceded, Gonzales found a new cause. He threw himself into the Confederate war effort with the same enthusiasm he exhibited in the cause of Cuba libre. He joined the staff of General Beauregard as a captain and an assistant inspector general. He became a lieutenant colonel of South Carolina state troops in May 1861.

Gonzales was associated with his old classmate and friend, General Beauregard throughout much of his Confederate career and was an aide during the bombardment of Fort Sumter. He also looked so much like Beauregard, they were frequently mistaken for each other. After Beauregard left for Virginia, Gonzales was involved in the strengthening of South Carolina’s coastal defenses as a special aide to Governor Pickens. He joined the Confederate Army as a lieutenant colonel on June 4, 1862, and served under Major General John C. Pemberton, who promoted him to chief of artillery for the Department of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida on August 14. He was promoted to colonel that same day.

Colonel Gonzales served as chief of artillery from 1862 until 1865. He was deeply involved in the successful defense of Charleston from 1862 to 1864, and particularly distinguished himself at the Battle of Honey Hill, South Carolina, on November 30, 1864. Here part of Sherman’s forces tried to cut the Charleston and Savannah Railroad. The battle is historically significant because most of the 5,000 Yankees involved were African Americans, making it the first battle in U.S. history fought primarily by African American soldiers. The famous 54th Massachusetts was part of the attacking force. The Rebels totaled 1,400 men (mostly Georgia Militia) and seven guns, but their position was extremely well selected, and they were too well entrenched to be dislodged. The Federals were also badly cut up by Southern artillery. Major General Gustavus W. Smith, the commander of the Georgia Militia, reported: “I have never seen pieces more skillfully employed or more gallantry served upon a difficult field of battle.” The Union Army suffered 89 killed, 629 wounded, and 28 missing, as opposed to eight killed and 39 wounded for the Southerners.[5]

A. J. Gonzales was promoted to chief of artillery of the Army of Tennessee in 1865. Beauregard and Pemberton recommended him for promotion to brigadier general, but no action was taken by the end of the war. As part of the surrender of the Army of Tennessee, Gonzales was paroled on April 30, 1865.[6]

After the surrender, Gonzales tried to rebuild the family’s fortunes and labored in Charleston as a merchant, mill owner, and planter. Like many in the post-war South, he was not successful and basically went broke. He later worked as a teacher and translator but eked out a bare living with inadequate means. He lived in Cuba, Baltimore, and Washington, D.C., before he died in New York City on July 31, 1893. He is buried in Woodlawn Cemetery, the Bronx.

*************

[1] Perhaps the most famous Hispanic Confederate was Colonel Santos Benavides (1823-1891), a highly successful merchant, mayor of Laredo, and a noted Texas Ranger. He commanded the 33rd Texas Cavalry Regiment during the war, successfully and skillfully defended Laredo from the Federals, and won the thanks of the Texas legislature. He was recommended for promotion to brigadier general but the appointment had not been made when Richmond fell. He was a member of the Texas House of Representatives after the war. Bruce S. Allardice, Confederate Colonels (Columbia, Missouri: 2008), p. 60.

[2] Mallory (1812-1873) was a U.S. senator (1851-1861) and the only secretary of the navy the Confederacy ever had. After the war, he was charged with treason and imprisoned for a year but was never tried.

[3] Gonzales did not take part in General Lopez’s 1851 invasion of Cuba. Lopez was captured and executed by the Spanish that same year.

[4] Ulysses Robert Brooks, Stories of the confederacy, (Columbia, South Carolina: 1913), pp. 286-291.

[5] See The Official Records of the War of the Rebellion, Series I, Volume XLIV (Washington, D.C.: 1893), pp. 971-975.

[6] Brooks, pp. 292-302; Allardice, Colonels, 146.

Note: The views expressed on abbevilleinstitute.org are not necessarily those of the Abbeville Institute.

And salute this month to my collateral ancestor Severo Y’barbo of the Second Louisiana Cavalry , Company B. He was a descendant of Gil Antonio Y’barbo, founder of Nacogdoches and supplier of cattle for the Galvez Cattle Drive that provisioned Spanish forces along the Mississippi River and Gulf Coast as well as the American Continental Army during the War for American Independence.

You come from good stock Mr Bergeron.

DEO VINDICE

Interesting read, and thanks for publishing it. I shall forward it to my Cuban uncle, who I think will enjoy it. Nevertheless, I cannot refrain from commenting on the SCV’s declaration of “Hispanic Confederate Heritage Month”, in the hopes that some on our side of Southern heritage issues will take heed.

It’s just fine and dandy that the Confederate Army was “ethnically diverse”, if by that term we mean consisting overwhelmingly of various strains of European stock. But there’s something about marking “Hispanic Confederate Heritage Month” (or “Black Confederate Heritage Month”) that smacks of pathetic desperation. It’s as if the SCV (and by extension, everyone on our side of heritage issues) is saying, “See how progressive we are! We had Latinos – excuse me, Latinxes – and Blacks on our side, too!” Please. That’s just as sad and pathetic as hearing someone say “I’m not a racist, I have black and latino friends, too!” The minute we proceed down that road, it’s over. Nothing good comes from trying to out-Progressive the Progressives. It’s a loser’s game, and I’m sick of seeing our side play it.

The only way to win the game is to refuse to play. The Confederate Army was overwhelmingly composed of men of English/Scottish/Irish stock. There’s absolutely nothing wrong with celebrating that fact. The SCV and others on our side need to stop implicitly apologizing for it by seeking to celebrate exceptions to this rule. Such celebrations are little more than interesting sidebars to the main story, which serve only to provide aid and comfort to the enemy.

You know what, Houston? I’m Hispanic and I completely agree with you. Frankly, this thing about declaring a “Hispanic Confederate Heritage Month” just sounds ridiculous. It’s pandering, patronizing and just plain disingenuous. I’m more than fed up with this whole “diversity” craze at this point. Of course, it’s only diverse by what they choose to define it as, which is really just a euphemism for “less white”. The fact that the Confederate Army did consist of various strains of European stock technically already fits that description on its own, but that’s beside the point. It’s not as if race is the only metric you can apply it to.

The Confederate military did consist mainly of English/Irish/Scottish stock and that is perfectly fine to acknowledge and celebrate because it simply reflects the reality of the whole thing. Not being one of the majority has never bothered me. All I knew was that I’m American (or should I say New Yorker specifically) and that was it. I’ve never felt insecure about my place in this country. As soon as I understood what it means to adopt and assimilate to the host culture, I made it my goal to do exactly that. I get the sense that’s why I often felt like something of a black sheep among a lot of other Latinos I’ve interacted with growing up. Even though my family history here doesn’t extend nearly that far back, and I wasn’t raised in the South, I intend to help folks down there to protect and preserve what was passed down to them in any way I can. A good place to start is, like you said, not playing this pathetic game of “outdoing” the Progressives because we need to play by our own rules, never theirs. We have nothing to prove or justify to those people.

Learning about blacks and others in the Confederate armed forces did peak my curiosity because given the education I had, I was only presented with this hollow and one-dimensional interpretation with a lot I was either not told or was misled about. But I also understood that they only made up a fraction of the whole, and that’sperfectly fine. They do make interesting little sidebars to the main story, but have to be recognized as such, we wouldn’t be doing anybody any favors by making them out to be something bigger than what they were.

The piece published today by Samuel Mitcham was about Hispanics who fought for the South, but it mentioned the “diversity” of the Confederate Army. You might not be aware of Thomas’ Legion, a unit of the North Carolina army that fought from western NC all the way up the Blue Ridge to Potomac, MD, and back before surrendering in Waynesville, NC, three weeks after Lee surrendered at Appomattox. William Thomas, born near Waynesville, was a U.S. Congressman before the war, and his force of 400 white men and 400 Cherokee Indians fought together. Thomas was elected the first white chief of the Eastern Cherokee nation after he persuaded Congress to give the land for the NC Cherokee reservation. My great-grandfather, Robert Taylor Conley, was an officer in Thomas’ Legion, and he fired the last shot of the war east of the Mississippi River on the night before they surrendered. There is a monument in Waynesville commemorating the event, erected by the UDC.

Wonderful history, elegantly written and, as always, very thought provoking.

I don’t mean to ask but are there any Confederate soldiers from Puerto Rico? I know there was once Puerto named Augusto Rodriguez but was on the side of the US Army. He was born in Puerto Rico in 1840 and immigrated with his family to the US in the 1850s. He became a naturalized citizen in his early 20s and served in the US Army as a lieutenant colonel. He served in my home state of Connecticut which has the largest population of Puerto Ricans of any state in the union with more than New York or Florida which the average person would assume but it’s actually Connecticut where 95% of them congregate. Half the country’s population lives in the small state and has replaced the native white populations that once flourished in the province’s cities. After the war he lived out his remaining years in New Haven and became a fireman for the city’s fire department. He died of tuberculosis in 1880 but left a legacy that the mainstream press rarely and refuses to speak about. He was one of the first Puerto Ricans to ever immigrate to the US and settle in New England which the Hispanic population at the time was zero but now has blown out to a population the size of NYC.

That’s the only Puerto I know of that served in the army. But were there any that served in the Confederacy at all?

Let me know if anyone has answers.

Have a blessed day.

Yes, Vince, there was at least one Puerto Rican Confederate soldier that I know of but I can’t remember his name and/or rank.

Yes, Vince, there was at least one Puerto Rican Confederate soldier that I know of but I can’t remember his name and/or rank.