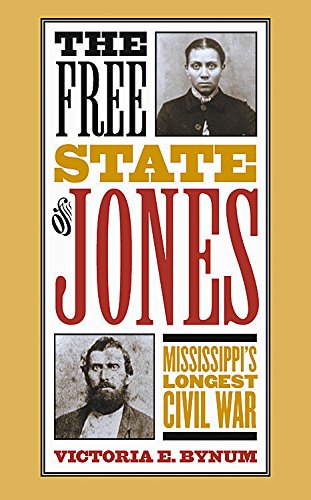

A review of The Free State of Jones: Mississippi’s Longest Civil War (University of North Carolina Press, 2001) by Victoria E. Bynum

The film loosely derived from this book has already been reviewed here by historian Ryan Walters – ably so, since he grew up in Jones County, the “free state” in that title. But the key question raised by the book is not addressed:

If secession is a right, where does it stop? If states can secede, can every county? If every county, can every city and village? Every family and every man?

This question is directly addressed by Brion McClanahan in his show “Is American Secession Workable,” at the 26:08 mark, where he analyzes R.D. Griffiths’ thoughts on this subject. There McClanahan points out that States are the current governmental building blocks, which created the Union as well as their Counties. The current Constitution provides an apparatus for this question, in Article IV, Section 3, where the text clearly details that States may be joined or subdivided only with “the Consent of the Legislatures of the States concerned as well as of the Congress.” Secession by a county cannot be the same as secession by a State, since the State held the power to create, or to choose not to create, any subordinate administrative district it wants. In brief: The county is the creature of the State.

But this observation, while true, opens up the following difficulty: The original American States were creatures of the British Crown. George III had the power to grant the charters that created them, or to withhold them. By this reasoning, the secession that created the United States – for it was indeed a secession, and not a civil war or a revolution – was illegal.

It seems that the only course is to concede the theoretical point that the principle of secession is unbounded, as economist Ludwig von Mises does, and simply institutionalize the process as sensibly as possible, as I do in Field Guide to Texas Secession, page 149.

Historically of course, the intramural question doesn’t apply among the Southern States. Each of them recognized the sovereignty of the others, and each of them freely entered the Union as a sovereign state, with the right to leave at any time. If there is a single fact proving that the Union was voluntary, it is the fact that North Carolina and Rhode Island didn’t ratify the Constitution until after George Washington was sworn in as president: The United States existed without their voluntary membership, and would have existed if they had never joined, or if others had opted out. By seceding and fighting a purely defensive war, the Southern States were upholding the original meaning of the Constitution. They were the true patriots to the meaning of America; the Northern States were invaders seeking to impose an ideology alien to that of the Founders.

Nevertheless, one county — Jones County, Mississippi — did secede from its State during the War of Northern Aggression, and it offers a vitally important laboratory example of the principle of unlimited secession. It also suggests why poor whites fought a war that may not have been obviously in their interests as a class.

Following the Confederate loss at the Second Battle of Corinth, Mississippi (October 3-4, 1862), desertions among Mississippi forces became a problem (Bynum, page 100). After the fall of Vicksburg (July 4, 1863), desertions further increased (p.96). A group of desperate soldiers had written the following to General Pemberton before that surrender:

If you can’t feed us, you had better surrender us, horrible as the idea is, than suffer this noble army to disgrace themselves by desertion. I tell you plainly, men are not going to lie here and perish (p.104).

The besieged army did surrender, and as a condition of their release the soldiers signed a pledge not to fight again. Of course the Confederate authorities thought that pledge null and void, and insisted that the released men continue fighting or face imprisonment.

One of the Mississippians imprisoned for desertion, in January or February of 1863, was John “Newt” Knight of Jones County. As the date of his imprisonment makes clear, his desertion wasn’t due to a lofty sense of honor for a pledge signed at Vicksburg. Victoria Bynum’s book attempts to explain this defiance that pressed him not just to desertion but to a complete secession from authority.

Absent from the list of causes is any real concern for ideology (p.97), we must note at the start. Texans are likely familiar with the anti-Confederate enclave of Germans (die Treue der Union) in the Hill Country, 34 of whom were massacred in Comfort in 1862, who did oppose the war for ideological reasons. This is not to say that those in Mississippi were a bunch of ignorant white trash clay eaters as “wild as the deer” (p.23), who fought or deserted on a whim. They had their own reasons.

Those reasons, Bynum carefully explains, originated in a long history that started in the pre-Revolutionary frontier of North Carolina. She notes that from the beginning there was a tension between the tidewater aristocrats and the back country “yeoman farmers.” This tension expressed itself in many Southern institutions, as my following table — taken from her initial chapters — tries to suggest.

| Backwoods farmer | Tidewater aristocrat | |

| Politics | Tory (for its being “anti-Whig”) | Whig (promoting business interests) |

| Religion | New Light (free-spirited, leveling) | Baptist (rigid, protecting status quo) |

| Police | Regulators (similar to Tea Partiers) | Moderators (like Republicans/Democrats) |

| Slavery | No or few slaves | Many slaves |

| Home | Piney woods | Piedmont |

| Livelihood | Subsistence; corn as cash crop | Wealthy; cotton as cash crop |

| Race | Mixed, lacking taboos | Pure, protected by taboos |

As the tidewater aristocrats took control of the leading institutions (the government, the church, the police, the economy), the backwoods farmers tended to just pull up stakes and move further into the frontier. From western North Carolina, they moved to the area in South Carolina along the Savannah River, and as the pattern repeated itself, from there along the Federal Road between Augusta and Mobile. At the beginning of 1820, Mississippi was Indian country except for a few counties along the gulf, and many of these frontiersmen intermarried with them.

Knowing this history, it becomes easier to understand why a backwoods man like the aforementioned John “Newt” Knight might think it reasonable to declare the piney woods county of Jones to be a free State sometime in 1863, and to fight some 14 pitched battles with Confederate authorities to defend it.

This history also provides a laboratory, as mentioned, for those who would study secession as the thin edge of a wedge that ends in anarchy. Newt Knight seems almost blessed with two historians among his ancestors who provided perfectly opposing views of his motives: Ethel Knight, who describes him as an outlaw, and Tom Knight, who describes him as a harassed poor man defending his own (p.106). (The previously cited Ryan Walters takes the former view.) Considering the facts where they, and other historians, have no dispute, it seems that Newt Knight was more restrained than his tormentors. It is likely that he murdered one Bill Morgan (p.100), but the man had taken over his family and property while Newt was at war. And it is likely that he murdered Confederate Major Amos McLemore (p.105), but this man was leader of a barbarous policy against him and his fellow secessionists (who never numbered more than 150; p.116). This policy included gruesome judgments without trial, where the hanged men were left to rot in their nooses until their relatives cut them down (p.116), where 13-year-old boys were hanged and left to rot (p.118), where the secessionists’ property was despoiled and all their food, livestock and horses taken (pp.123, 126), where their weddings were attacked (p.127). If there is a lesson to be drawn from this laboratory, it is to note that the violence of the secessionist “outlaw” is usually defensive and more restrained than the organized violence of the forces of “law and order” who believe themselves in possession of a moral right to exercise that violence. Indeed, isn’t this the lesson of the greater war itself? And note carefully: The very terms of discussion weigh against the one who is outside the established institutions, whose killings are called “murders,” while established law gets the presumption of rightness, no matter how unrestrained and disproportional it may be.

Furthermore, this history takes us a long way in answering a question that has vexed many: Why in the name of heaven did these poor whites fight at all, when the main beneficiaries of their sacrifice were a relative few wealthy slaveholders? (On this subject, I may end up reviewing Joe Bageant’s Deer Hunting with Jesus before it’s over with.) I take no stock in any notion that a significant majority is motivated by ideas. It just ain’t in nature. But I do believe that when a man can visualize his family under attack, he will fight not just to his last bullet, but with his bare hands. War fever can paint this kind of picture for him, and can get him to volunteer for a year of fighting. And what then, after a year’s worth of the reality of war? This is why the Confederacy had to pass the First Conscription Act exactly a year after Fort Sumter, forcing men 18 to 35 into service. This was galling to the ordinary Southern soldier, especially since a conscripted man had no choice in who led him into battle, and no choice of who fought alongside him (p.99) – practices contrary to the formation of Southern units by known compatriots of each community. Later that year a more bitter law, the Twenty Negro Law, was enacted a few weeks after Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, devised in September 22, 1862 (p.98). Southerners believed that Lincoln gave the proclamation the following January 1 in order to deliberately foment a slave revolt. So, to return a few able-bodied men home to defend plantations often left in the care of women, old men, and minors, the Twenty Negro Law exempted one white male from military service for every 20 slaves as long as he was overseeing slaves. After its enactment, the Southern soldier groused about “a rich man’s war, a poor man’s fight.”

So can conscription explain the valor of the Southern soldier? A fool would believe that. More likely the men who, ragged and starving, fought all the way to Appomattox were motivated by just two things: A desire not to let down their band of brothers in arms, and by a primitive patriotism that fights not for ideas but for a stand of pine trees in a clearing of red clay, for a peculiar way of saying things and saying the unsaid, for the prospects of children not yet born, for the familiar bark of the dog on the approach to home, for all those things nearest the heart – for Faulkner’s “old verities.”

The Free State of Jones goes a long way in describing the motivations of poor Southern whites in the War of Northern Aggression, and it allows you to visualize them as real people, but I must say that you have to read between the lines to get at it. Victoria Bynum does not have the gift of a natural storyteller like Shelby Foote or Thomas Fleming, and nearly half the book is devoted to footnotes and forgettable family trees.

Secession is only a question because it interferes with accumulating and consolidating more power. I’m sure Northern or Southern Editorials cover the question of county secession… but with respect to power, you can see below the central government wanted to bind men and State to central authority:

Southern Editorials on Secession provides:

False Issues on Which It Is Sought to Rest the Canvass for the Presidency

Richmond Semi-weekly Examiner, October 26, 1860

It has always been the habit of those who seek to obtain power, rather than to establish a wise policy and sound principles, by popular elections, to raise false issues and avoid the real questions before the people. In no contest that we remember has this policy been more persistently and recklessly pursued than by the opponents of State and Southern rights in this canvass. –The issues presented in this canvass are few, simple and distinct. Every man can see and the dullest can comprehend them.

In the progress of our Confederacy, from its infancy to its present maturity of power, the strength and weakness of the federative, limited system of our polity has been both developed and tested. The long struggle between those who thought the Federal Government too weak and those who sought to limit its powers has been continuous, and events have demonstrated that there was no need of strengthening, but much of restraining the powers of the general agent of the States. The opponents of the Democracy and of the rights of the States having tried to increase the power of the Federal Government, by direct legislation, by building up a system of monopolizing class legislation, binding men and States to the support of the Federal agency by the bonds of a sordid pecuniary interest, have failed; and this failure has been caused by the conclusive conviction of the people that the agent of the Union — the Government of the Confederacy — had abundant strength of itself without adventitious and unconstitutional additions to its powers.

Mr. Hulsey comments in closing that we need to “read between the lines” of The Free State of Jones to get at why poor white people had fought against the Yankees. He does that very, very well in the penultimate paragraph. Edited only slightly:

“The men who, ragged and starving, fought all the way to Appomattox were motivated by just two things: A desire not to let down their band of brothers in arms, and by a primitive patriotism that fights not for ideas but for a stand of pine trees in a clearing of red clay, for peculiar way of saying things and saying the unsaid, for the prospects of children not yet born, for the familiar bark of the dog on the approach to home, for all those things nearest to the heart.”

There’s a vignette at the end of Lee’s Miserables by J. Tracy Power in which the above nearly matches the visual and thoughts of a soldier, Sgt. Whitehorne, approaching home in Greensville Co., Va. after Appomattox. The description won’t satisfy the consensus that insists the War was fought for the lust of owning people – hell, they wouldn’t have the the courage and the span of attention to listen to it. Maybe somewhere between this and Shelby Foote’s anecdote of the reason for fighting given to his captors by a Rebel soldier: “Because you’re here”.

Well done.

I believe that succession should not stop until it extends to each individual controlling and responsible for their own life, their own actions and beliefs and their own property. I don’t equate ‘anarchy’ with ‘chaos’ because in my own experience and awareness of past history I see actual chaos stemming from the hubris of rulership; of people believing they have the right to control and dictate how others should live. This meddling arrogance is most frequently displayed by those with a clear inability to even run their own lives with any fidelity to a genuinely ethical sense of right behavior; in large measure because they have shirked and neglected it in preference to ruling others and, predictably, also failing at that. This type of human usually justifies their meddling presumption with claims of benevolence and good intentions that are transparently belied by their plain acts of parasitism and plunder conducted with violence which are really in the service of power and control for their benefit alone. That the majority sycophantically submits to this sordid and detrimental oppression is an even sadder reality than the wickedness of rulership itself.

The problem in ALL of these issues is not secession or its lack or government (at least that which is not tyranny!) or even cultural differences. The problem is the HONESTY and DECENCY of those involved. I would rather deal with an honest man with whom I have a disagreement than a dishonest man who supposedly believes as I do. Why? First, because he is dishonest, I cannot believe him when he SAYS he believes as I do. Secondly, a lack of honesty means a lack of every other moral principle that contributes to a successful relationship whether it is personal, familial, cultural or civil. When you cannot believe those who rule over you, you are entirely helpless to protect yourself and a sure way to know that such is the case is when you deal with “leaders” and “governments” who want to disarm you. It is not for nothing that the SECOND Amendment to the Constitution concerns the right to bear arms. In history, no mass murder of any population occurred before the people were disarmed! It makes no sense to argue deeply about what needs to be done or said or believed in order to return to at least a somewhat decent government until you remove AND PUNISH those whose criminal behavior has brought us to our present situation. Unfortunately, from what I can see, there are far more of them than there are of us.

i have read that it took until 1851 for non-landed whites to be able to vote in Virginia. for the period and era…this sounds like state change at the class level. McLanahan has essentially described Jefferson as a state-level progressive for the era. I’m not sure how poor southern whites (my ancestors) would have benefitted from continued northern overlordship either. once the sovereign states had seceded and invasion begun – good luck to to the single county to convince the northern armies to just ‘let them alone’.

I prefer leveraging the Convention of States to use Article V and amend the constitution so that the 38 state (or more) super majority can, at its discretion, kick states out! Like the famous line from Animal House, think it was D Day – don’t get mad – get even. Good bye California and Massachusetts. Even if all of New England and New York City/Long Island could be booted – we still outnumber them 3-1, out GDP them the same 3-1 and out-enlisted personnel 4-1.

Thirteen Bars – Forty Stars!!

The Germans were 48ers…communists run out of Europe for pretending men were all entitled to equal portions due to their birth…as non-sensical as the belief that men should be rewarded for their individual efforts in our modern times.

If you want to know why the Scots fought the Romans at Hadrian’s Wall or why the Scots-Irish were eager to kill the king’s men at King’s Mountain or why the Scots-Irish were eager to kill yankees in the War Between the Free States (well, except for the 5 Slave States that were in the “union”) and the Slave States (Slave States where free blacks COULD live and own property (including slaves) and where BT Washington said they loved their masters) it’s because it’s in our blood to resist authority since in our ancestral DNA there resides a undeniable urge to tell jackasses where they can go to get off the train.

It’s why I and my family never took the vaxxine jab…because deep in my ancestral DNA, I know ABSOLUTE IDIOTS ARE SOMEHOW APPOINTED OVER ME TO MAKE STUPID RULES.

I also know these morons lie without cease and previously, in history, they were able to control the narrative (WHICH IS WHY THE SLAVE NARRATIVES NEVER SAW THE LIGHT OF DAY PRIOR TO THE INTERNET AGE-or perhaps YOU CAN SHOW ME A UNION TEXTBOOK WHICH INCLUDES A SAMPLING OF THE “WE WERE BETTER OFF AS SLAVES THAN UNDER THE ROOSEVELT ADMINISTRATION”) but now the “masters” are in a panic over FAKE NEWS which reports on THOUSANDS OF FREE BLACKS FIGHTING VOLUNTARILY FOR THE CONFEDERACY ALONG WITH THE FIVE CIVILIZED TRIBES BECAUSE APPARENTLY deep in their ancestral DNA they knew the yankee masters were absolute idiots who had no business telling us what to do with our lives.

Yep, that’s right…not only did poor, free Whites fight against oppressive government but SO DID ALL THE OTHER COLORS.