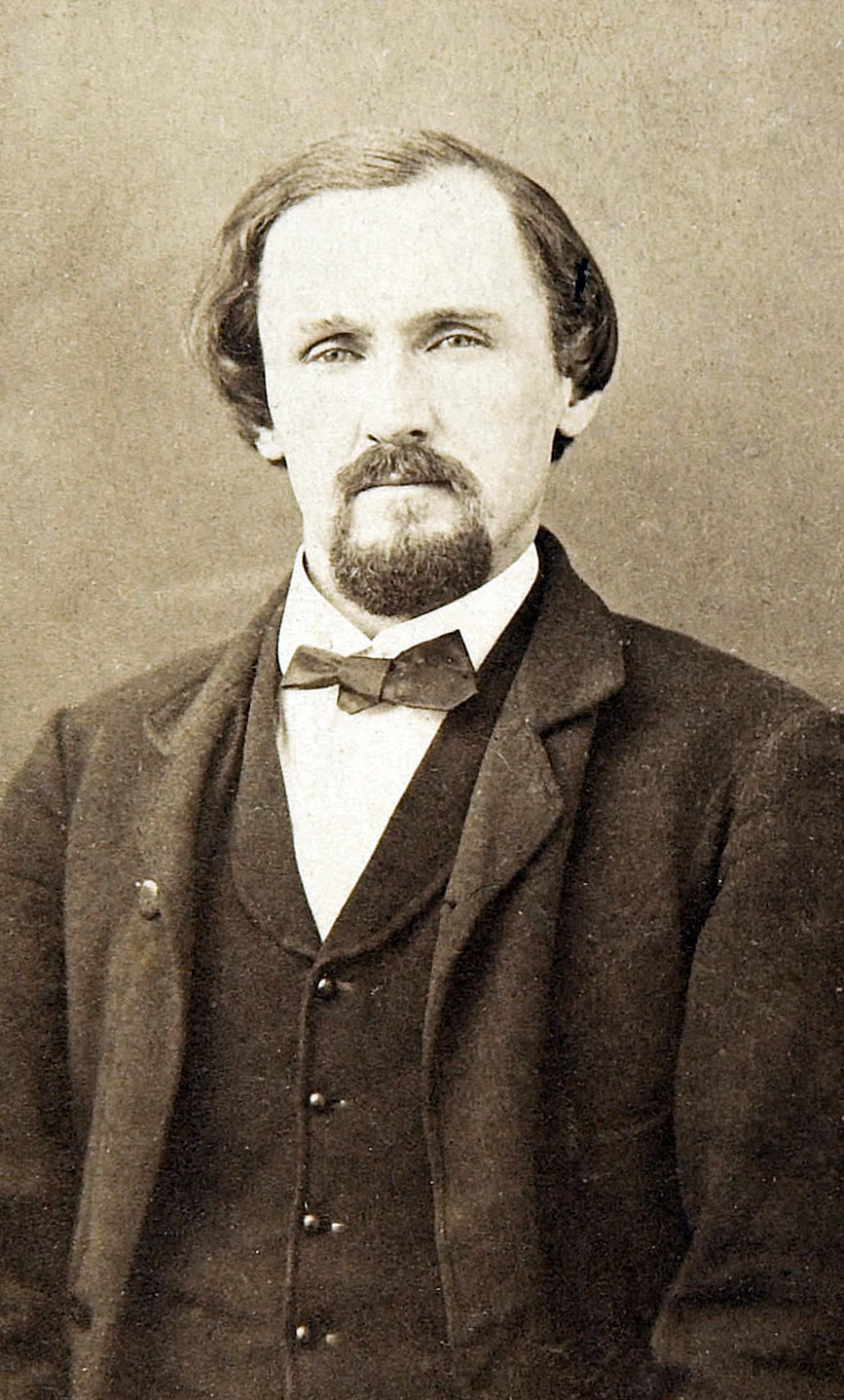

I just finished John Headly’s book “Confederate Operations in Canada and New York.” It’s a good read and provides great insight into Confederate operations in New York and other northern states. I highly recommend it. But this piece isn’t about Headly. It’s about John Yates Beall, acting master in the Confederate States Navy. In this book, Headly poignantly describes the execution of Beal and how he calmly and bravely faced death at the hands of the Union.

John Beall started out in the war as a member of the 2nd Virginia Infantry, Co G, Confederate States Army. I won’t go into much of this part of his service, but I will add that he received a gunshot to a lung which rendered him incapable of active service.

Recovering somewhat, and being inspired by General John Morgan, Beall presented a plan to Confederate authorities to operate privateers in the Great Lakes. The plan was not accepted. However, the Confederate government did commission Beall as an acting master in the Confederate Navy.

Beall commandeered two boats and operated in the Potomac and Chesapeake Bay area and was captured by Union forces in 1863 and was held as a prisoner of war at Fort McHenry until his release in a prisoner exchange in May of 1864. Upon his release, he headed to Canada and devised a plan to commandere a boat to aid in the release of Confederate prisoners being held on Johnson’s Island. This plan was not successful due to his crew not wanting to carry through without further outside assistance.

Beall reluctantly sailed back to Canada where he and a cohort, George Anderson, came up with another plan to free Confederate prisoners being held at Fort Lafayette in New York. Both he and Anderson were captured in December of 1864 and held at Fort Lafayette. Anderson agreed to testify against Beall in this matter.

Beall was brought before a Union commission, charged with espionage, found guilty, and sentenced to be hung. Now bear in mind that this was not espionage, but an attempt to free Confederate soldiers, in the service of his country, far, far less than the war crimes committed all across the South by Sherman, Sheridan, and Stoneman.

On February 14, 1864, Beall wrote to his brother, Will. In this letter, he states that “I am not aware of committing any crime against society. I die for my country. No thirst for blood or lucre animated me in any course” and that “my hands are clear of any blood unless it be spilt in conflict, and not a cent enriches my pocket.”

On this same day, Beall wrote a letter to a James McClure. In it, he states, “I am not a spy nor a guerrilla. The execution of the sentence will be murder.”

There were attempts to persuade President Lincoln to stay the execution, by such notables as Rev. Dr. Bullock of Baltimore and ex-Senator O.H. Browning of Illinois, and a petition signed by ninety-one members of Congress. However, Lincoln did not intervene.

On the day before his execution, he was visited in his cell by Rev. Joshua Van Dyke, of Brooklyn. Van Dyke writes that he found Beall to be “at every turn the gentleman, the scholar, and the Christian…He did not use one bitter or angry expression towards his enemies, but calmly declared his conviction that he was to be executed contrary to the laws of civilized warfare. He accepted his doom as the will of God.”

Headly writes that at half past one P.M. on February 24, 1865, Beall was taken from his cell and marched to the gallows. As the band played the death march, Beall “caught step” with the Union regulars, marching in time with them because in Headly’s words, Beall “was a soldier and knew how to keep step even to the music of his own death dirge.”

The procession arrived at the gallows and came to a halt. There stood Beall, at the foot of the gallows, looking at the rope, and the pine coffin at the base of the gallows. “For nine solid minutes, by the watch” Beall stood face to face, in silence, with his destiny. He could have turned his face away but he did not.

Beall mounts the platform and takes a seat under the rope that will soon be placed around his neck. Lieutenant Keiser, Adjutant of the Post, begins to read the charges and the order for the execution. Beall respectfully stands for this reading. He hears himself designated as a “citizen of the insurgent state of Virginia” and he smiles, “not in derision, but in protest and remonstrance” at Virginia being described as an insurgent state. When he is described as a “guerilla,” he stops smiling and “shakes his head in denial.” He laughs “outright” as he hears the concluding passage of the order, which describes his attempts to destroy the lives of New Yorkers. Headly indicates that Beall undoubtedly sees the hypocrisy here, as a Union officer is reading this…and as Beall remembers how his beloved Shenandoah Valley was burned out by Federals.

As Beall respectfully stands for this reading, his back is towards Lieutenant Keiser. Headly describes that Beall did as “the martyr sets his face towards Jerusalem or the Mussleman toward the shrine of Mecca, so this hero dying for the faith of his fathers, turns his face upon the South.” At the end of this reading, Beall turns towards the officer of the day, and in a “calm, firm voice” he spoke these words; “I protest against the execution of this sentence. It is a murder! I die in the service and defense of my country! I have nothing more to say.” At this point, the signal is given, the trap door opens, the rope tightens, and the execution takes place.

I realize this is a bit lengthy, but Bealls’s story deserves to be told…that he was executed for simply trying to free his fellow soldiers. John Beall is not a well-known Confederate soldier like Jackson, Lee, Pettigrew, Forrest, etc. But he is nonetheless just as much a true Southern hero. May we all have the courage to face death as he did, calmly and bravely with our faces turned towards our beloved South.

Deo Vindice.

Deo Vindice Resurgam.

Thank you.

Thank you.

Thank you for this story.

God bless John Beall for his resolve, his bravery and his steadfast support of his state and the southland.

A true Confederate hero and example of Christian manhood, worthy of remembrance.

Thank you.

Mary Surratt, Henry Wirz, John Beall, God grant their souls eternal and gentle repose. They were among the many victims of a Godless and unspeakable regime.

There were six men of Col. John Mosby’s Partisan Rangers, David L. Jones, Lucian Love, Thomas E. Anderson, Henry C. Rhodes, William Thomas Overby and one remembered only as Carter, murdered not long after Grant endorsed treatment of captured Mosby’s “guerrilla’s” – “hang them without trial”.

The first four were shot to death, including Henry C. Rhodes, 17 years old, who was first dragged, tied between two horses. Witnessed by townspeople, including his mother, a federal soldier forced him to stand as he emptied his revolver. The last, Overby and Carter, were hung after refusing to betray Mosby”s whereabouts.

We could be here all night.

Then let it go all night.

They’d be happy to be remembered.

It may be a good thing I didn’t see your reply last night.

Yes, we have the duty to remember them. I’ve been reading much about the VMI Cadets at New Market. There is a focus on one, Thomas Garland Jefferson, who is sort of family. I’ve looked at the one photograph of the young man for hours to the point that it feels like a conversation; it seems like I’m only saying “goodnight” when I put the book down. He tells me of the home and family he left and the life he never got to live, yet, there doesn’t appear any resentment of his fate.

I suppose the defiant resolve of John Yates Beall, Sam Davis and others influence my imagination.

All of the men who fought to defend their homes should be honored.

My ancestors stopped the Romans at Hadrian’s Wall.

They beat down the Brits at King’s Mountain (ironic, isn’t it?), Cowpens and Yorktown after being sentenced to transportation to the colonies.

They fought in all of this country’s wars. I am the last. I have told my children not to go to war for these people.

But, a month ago, something happened to end the war on western civilization. Those who have supported communism/globoccultism are wondering how they could have not foreseen the unintended consequences of their actions.

This internet is a wonderful invention. All of the lies are being exposed.

Soon, Harvard researchers will discover the Corwin Amendment. And they will discover the honor in men such as John Yates Beall and Sam Davis.

Great Read!

Thanks for illuminating a hero of the South that I had not heard of before. He was determined and stoic. May he rest in peace and his memory honored.

Fascinating story. I am sure there are many other heroic confederate stories which have been buried by the match of time.

Thank you for allowing us to see this one.

I couldn’t say it any better than Mr. Whitfield, above, so I will repeat what he wrote: Thanks for illuminating a hero of the South that I had not heard of before. He was determined and stoic. May he rest in peace and his memory honored.