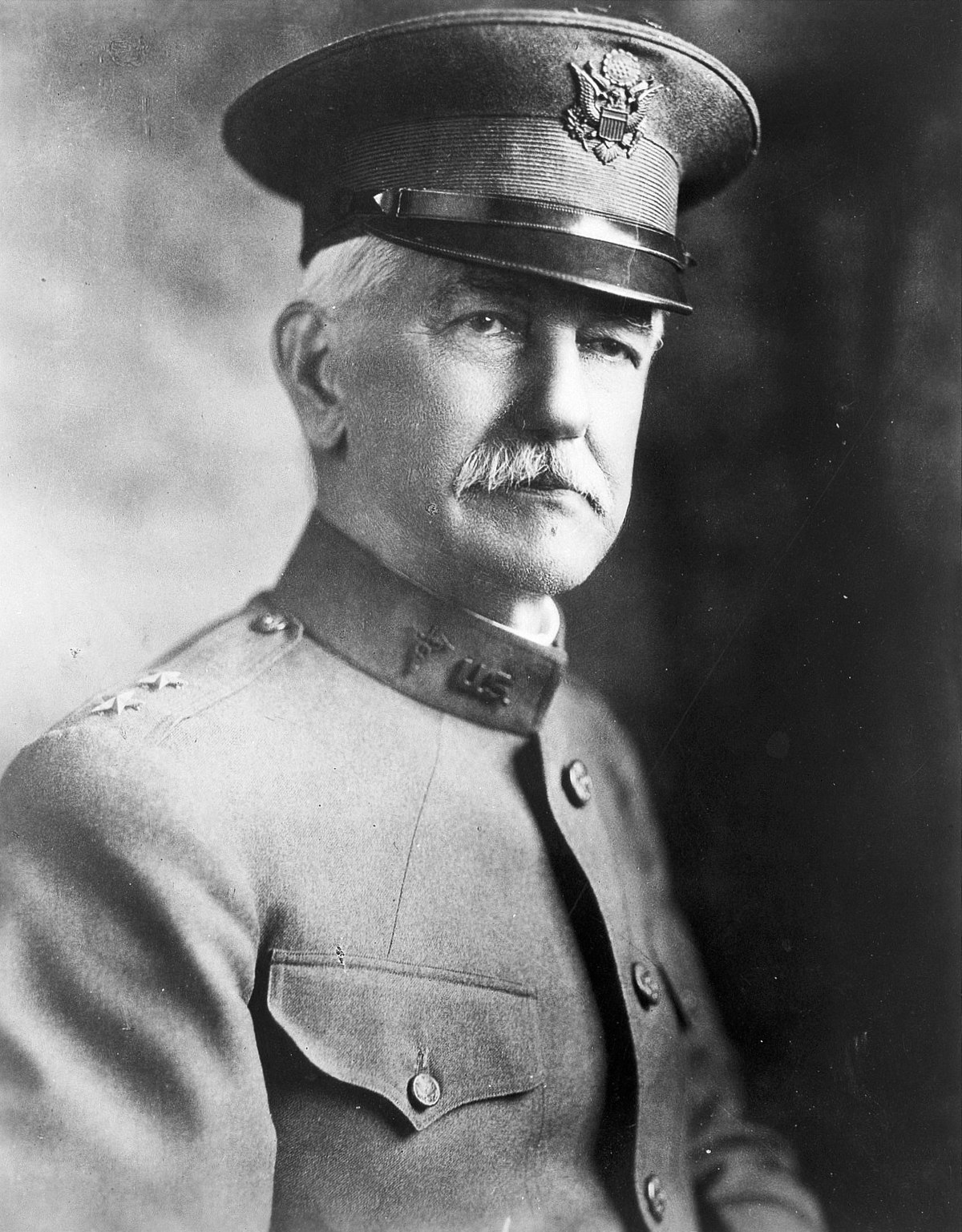

Colonel William Crawford Gorgas, son of Confederate general Josiah Gorgas, Jefferson Davis’ chief of ordnance, was already a world renowned doctor before he ever set foot in Panama. In the final days of the Spanish–American War, Gorgas was Chief Sanitary Officer in Havana, where he eradicated yellow fever and malaria by identifying its transmitter: the Aedes mosquito. (Previously, people had speculated the noxious, humid air of tropical and subtropical climates to be the culprit.) By attacking mosquito breeding ponds and quarantining yellow fever patients in screened service rooms, cases in Havana plunged from 784 to zero within a year.

According to classmates at Bellevue Medical College in New York, which he attended after receiving a bachelor of arts at the University of the South at Sewanee, “Billy” Gorgas was remembered as a devout Christian but careless speller, impoverished but extremely likable, and “imperturbable.” He believed the particulars of his life personally directed by God — not necessarily an unsubstantiated opinion, given that he met his wife in 1882 at Fort Brown, Texas when the two were convalescing from an outbreak of yellow-fever. Because of his immunity to the disease, Gorgas was regularly summoned for service whenever the disease broke out.

In 1904, Gorgas arrived in Panama, where the U.S. government had the year before helped engineer a revolution from the Colombian government in order to facilitate the construction of the Panama Canal. A quick survey of the Isthmus confirmed that the entire region was a “mosquito paradise,” which explained why thousands of Frenchmen had died of malaria during their disastrous attempt to build a canal there more than twenty years prior. Gorgas estimated that unless severe measures were taken to destroy the Aedes mosquito, the annual death toll in Panama during construction of the canal would be as many as three or four thousand people.

After much effort, Gorgas eventually persuaded his superiors to pursue the most costly, concentrated health campaign in the history of the world. More than four thousand men funded by a budget of hundreds of thousands of dollars (millions in today’s money) labored to defeat malaria and yellow fever. Panama City and Colon, on opposite ends of canal construction, were fumigated house by house, sometimes more than once. New yellow-fever cases were tracked down and closely monitored, while all major population centers were provided with running water instead of water containers, where mosquitoes had bred.

Eradication efforts in Panama — which also included draining of ponds and swamps and the use of mosquito netting — took a year and a half. But once Gorgas’ anti-mosquito program began, yellow fever incidence rates fell off dramatically. Within several months, the epidemic was over, and within a few more, the disease had disappeared from the Isthmus. Without Gorgas, who later served as president of the American Medical Association and then Surgeon General of the Army, the Panama Canal — through which 40 percent of U.S. container traffic moves annually — would very likely not exist.

Gorgas was not the only southerner at work in Panama. David du Bose Gaillard of Fulton Crossroads, South Carolina, was a U.S. Army engineer who was given responsibility for construction of the central portion of the canal, crossing the continental divide. In particular, Gaillard managed the notorious Culebra Cut, which required the removal of earth amounting to 96,000,00 cubic yards. At the bottom of the Culebra Cut, temperatures were usually well over 100 degrees. “Hell’s Gorge” is what one steam-shovel man called it. “He who did not see the Culebra Cut during the mighty work of excavation,” explained one contemporary author, “missed one of the greatest spectacles of the ages.”

Those who worked for Gaillard claimed he worked twelve hours per day. He is said to have checked up expenses on everything, reportedly saving the federal government $17,000,000 (how’s that for southern frugality!). Sadly, Gaillard did not live to see the opening of the Panama Canal in 1914, returning to the United States because of nervous exhaustion from overwork. He died of a brain tumor in 1913, and is buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

Another southerner, Lieutenant Colonel William L. Sibert, who later co-authored a book about the canal, was an ambitious, headstrong, high-spirited farm boy from Alabama who chewed on unlit cigars and wore ill-fitting clothes. Before arriving in Panama, the West Point graduate worked on the Soon Canal in the Great Lakes and managed a railroad in the Philippines.

From 1907 to 1914, Sibert served as a member of the Panama Canal Commission, managing the construction of several critical components of the canal, including the Gatun Locks and Dam, the West Breakwater in Colon, and the channel from Gatun Lake to the Pacific Ocean. These were all impressive engineer marvels in their own right, as David McCullough documents in his majestic The Path Between the Seas. When the United States entered World War I in April 1917, Sibert, by then a brigadier general, was breveted to major general and deployed with the American Expeditionary Forces to Europe, a position Sibert, a career engineer, adamantly admitted he was unqualified to hold. Sibert too is buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

The Canal Zone — which after completion of the canal was administered by the United States until the 1990s — retained, at least in the impression of many, a Southern character. It was “a small southern town transplanted into the middle of Central America,” Michael Donoghue cites one visitor noting in Borderland on the Isthmus: Race, Culture, and the Struggle for the Canal Zone. Many observers presumed that most canal inhabitants were from Dixie because the home port of the canal company was New Orleans, though a 1961 survey found that most Zonians, as they were called, were from the northeast and mid-Atlantic. (As the Panamanians began assuming control of the former zone, most Zonians emigrated to Florida and Texas.)

The perception of the Canal Zone as Southern is an odd one, given, as Herbert and Mary Knap explain in Red, White and Blue Paradise: The American Canal Zone in Panama, the canal community was the brainchild of some of the most progressive thinkers in America, and “full of union liberals.” Since everyone in the zone either worked for the canal company or served in the military, there was no unemployment, and residents all possessed the same standard issue… well, everything, down to the staplers. It was, in a sense, a socialist utopia.

Nevertheless, the Canal Zone was a curiously conservative place. Participation in voluntary associations, as well as church attendance rates were high, probably much higher than in the United States. Adultery, homosexuality, theft, public drunkenness, “anything that might interfere with the tranquility of the community,” was reason enough to ship someone home. It was, everyone agreed, a “great place to raise kids.”

The color line ran deep in the Canal Zone, something some observers speculated was the fault of the many southerners among the skilled workers and among the military officers. Others, including southerners themselves, attributed racial divisions to the influence of deeply color-conscious upper-class Panamanians. (I’d wager it was likelyboth.) Yet shortly after World War II, Zone administrators began to eliminate public segregation, and by the 1970s, racism had considerably diminished, according to the account of the progressive Knapps.

As a current resident of the former Canal Zone, I can attest to the peculiar character of the place, which in some respects reflects the vestiges of a charming Southern community. Zonians, who still live here in large numbers in former Zone communities such as Clayton, Albrook, and Diablo, all seem to know and take care of each other. All the Zonians I’ve met are religious, and call various parts of the South their other home. They are tremendously proud of what their ancestors accomplished in the tropical jungle of Central America, creating one of the greatest engineering feats in human history. Southerners, it is strange but true to say, built Panama.

“The color line ran deep in the Canal Zone, something some observers speculated was the fault of the many southerners among the skilled workers and among the military officers. Others, including southerners themselves, attributed racial divisions to the influence of deeply color-conscious upper-class Panamanians. (I’d wager it was likely both.)”

I got a hunch that you are right Mr. Chalk: “It was likely both.” But the case is constantly—constantly! Made to this day, that because of Southerners, either this or that would or would not have taken place. I served in the Marine Corps many, many years ago and I (and I am not the only one for dang sure) can state categorically from memory that while there was name-calling on both sides, Southerners were far more likely to call black marines “colored” and Northerners would call them n*****s. And they said it not in anger, but with relish.

A great article! I was stationed in Panama twice while I was in the Army. The first time was a temporary 6-month duty guarding Cubans while I was a paratrooper in the 82nd Airborne Division. We also went down a couple of times to the Jungle Operations Training Center (JOTC) at Ft. Sherman on the Caribbean side. I really liked Panama, and I reenlisted to be stationed there permanently. I was in A Co., 5/87th Infantry, and we were stationed at Ft. Kobbe in the late 90’s. It was inside the old Howard AFB on the Pacific side. I lived there for about 4 years all together, and I eventually rented a house in Panama City. We were one of the last units to leave in 1999 when we gave the bases back to the Panamanians, and we were sad to leave. Most of the people of Panama did not want us to leave either since the Chinese were buying up all of the land along the canal, and they were going to take our place once we left. I went to Gorgas Hospital many times on Ft. Clayton whenever I would get sick or hurt while training in the jungle. As far as racism went in Panama, the Panamanians themselves were much more racist than the average G.I. The pura sangre (pure bloods-old Spaniard stock) would not sit at the same table with a Mestiza (mixed Spanish and indigenous blood). A Mestiza would not sit with an indigenous person, and none of them would sit at the same table with an Afro-Caribbean of Jamaican heritage. There were also neighborhoods full of Chinese and South Asians who were hated by most of the Panamanians. If one soldier had a Mestiza girlfriend, and another soldier had an indigenous girlfriend, they would not sit at the same table together. I saw a lot of fights break out between girls of different races because they didn’t want to be seen in public with the other, even though they were all dating Americans. Whenever I hear people say, “America is a very racist country,” they have obviously not traveled much. In reality, most of the countries I traveled though in Latin America and Asia were much worse as far as race relations go. Thank you for the article, and a nice trip through memory lane.