From Mary Anna Jackson, Memoirs of Stonewall Jackson (1895) in honor of “Stonewall” Jackson’s birthday.

My own heart almost stood still under the weight of horror and apprehension which then oppressed me. This ghastly spectacle was a most unfitting preparation for my entrance into the presence of my stricken husband; but when I was soon afterwards summoned to his chamber, the sight which there met my eyes was far more appalling, and sent such a thrill of agony and heart-sinking through me as I had never known before! Oh, the fearful change since last I had seen him! It required the strongest effort of which I was capable to maintain my self-control. When he left me on the morning of the 29th, going forth so cheerfully and bravely to the call of duty, he was in the full flush of vigorous manhood, and during that last, blessed visit, I never saw him look so handsome, so happy, and so noble. Now, his fearful wounds, his mutilated arm, the scratches upon his face, and, above all, the desperate pneumonia, which was flushing his cheeks, oppressing his breathing, and benumbing his senses, wrung my soul with such grief and anguish as it had never before experienced. He had to be aroused to speak to me, and expressed much joy and thankfulness at seeing me; but he was too much affected by morphia to resist stupor, and soon seemed to lose the consciousness of my presence, except when I spoke or ministered to him. From the time I reached him he was too ill to notice or talk much, and he lay most of the time in a semi-conscious state; but when aroused, he recognized those about him and consciousness would return. Soon after I entered his room he was impressed by the woful anxiety and sadness betrayed in my face, and said: “My darling, you must cheer up, and not wear a long face. I love cheerfulness and brightness in a sick-room.” And he requested me to speak distinctly, as he wished to hear every word I said. Whenever he awakened from his stupor, he always had some endearing words to say to me, such as, “My darling, you are very much loved;” “You are one of the most precious little wives in the world.” He told me he knew I would be glad to take his place, but God knew what was best for us. Thinking it would cheer him more than anything else to see the baby in whom he had so delighted, I proposed several times to bring her to his bedside, but he always said, “Not yet; wait till I feel better.” He was invariably patient, never uttering a murmur or complaint. Sometimes, in slight delirium, he talked, and his mind was then generally upon his military duties-caring for his soldiers, and giving such directions as these: “Tell Major Hawkes to send forward provisions to the men;””Order A. P. Hill to prepare for action;” “Pass the infantry to the front,” etc. Our friends around us, seeing how critical was his condition, and how my whole time was given up to him, determined to send to Richmond for Mrs. Hoge to come to my relief, and assist in taking care of my baby. Hetty had been faithful to her little charge, but the presence of Mrs. Hoge, who was of a singularly bright, affectionate, and sympathetic nature, and her loving ministrations in this time of sorest trial, were of inestimable value and comfort.

Friday and Saturday passed in much the same way -bringing no favorable change to the dear sufferer; indeed, his fever and restlessness increased, and, although everything was done for his relief and benefit, he was growing perceptibly weaker. On Saturday evening, in the hope of soothing him, I proposed reading some selections from the Psalms. At first he replied that he was suffering too much to listen, but very soon he added: “Yes, we must never refuse that. Get the Bible and read them.

As night approached, and he grew more wearied, he requested me to sing to him-asking that the songs should be the most spiritual that could be selected. My brother Joseph assisted me in singing a few hymns, and at my husband’s request we concluded with the 51st Psalm in verse:

“Show pity, Lord; O Lord, forgive.”

The singing had a quieting effect, and he seemed to rest in perfect peace.

Dr. S. B. Morrison, a relative of mine, and Dr. David Tucker, of Richmond, had both been called in consultation by Dr. McGuire. As Dr. Morrison was examining the patient, he looked up pleasantly at him, and said, “That’s an old familiar face.

On Saturday afternoon he asked to see his chaplain, Mr. Lacy, but his respiration being now very difficult, it was not thought prudent for him to converse, and an attempt was made to dissuade him. But he was so persistent that it was deemed best to gratify him. When Mr. Lacy entered he inquired of him if he was trying to further those views of Sabbath observance of which he had spoken to him. Upon being assured that this was being done, he expressed much gratification, and talked for some time upon that subject-his last care and effort for the church of Christ being to secure the sanctification of the Lord’s day.

Apprehending the nearness of his end, Mr. Lacy wished to remain with him on Sunday, but he insisted that he should go, as usual, and preach to the soldiers. When Major Pendleton came to his bedside about noon, he inquired of him, “Who is preaching at headquarters to-day?” When told that Mr. Lacy was, and that the whole army was praying for him, he said, “Thank God; they are very kind.” As soon as the chaplain appeared at headquarters that morning, General Lee anxiously inquired after General Jackson’s condition, and upon hearing how hopeless it was, he exclaimed, with deep feeling: “Surely General Jackson must recover. God will not take him from us, now that we need him so much. Surely he will be spared to us, in answer to the many prayers which are offered for him.” And upon Mr. Lacy’s leaving, he said: “When you return, I trust you will find him better. When a suitable occasion offers, give him my love, and tell him that I wrestled in prayer for him last night as I never prayed, I believe, for myself.” Here his voice became choked with emotion, and he turned away to hide his intense feeling.

Shortly after the general’s fall, and before his situation had grown so critical, General Lee sent him, by a friend, the following message: “Give him my affectionate regards, and tell him to make haste and get well, and come back to me as soon as he can. He has lost his left arm, but I have lost my right arm.”

Mr. Lacy was truly a spiritual comforter and help to me in those dark and agonizing days. Often when I was called out of the sick-chamber to my little nursling, before returning we would meet together, and, bowing down before the throne of grace, pour out our hearts to God to spare that precious, useful life, if consistent with His will; for without this condition, which the Saviour himself enjoins, we dared not plead for that life, infinitely dearer, as it was, than my own.

In order to stimulate his fast-failing powers, he was offered some brandy and water, but he showed great repugnance to it, saying excitedly, “It tastes like fire, and cannot do me any good.” Early on Sunday morning, the 10th of May, I was called out of the sick-room by Dr. Morrison, who told me that the doctors, having done everything that human skill could devise to stay the hand of death, had lost all hope, and that my precious, brave, noble husband could not live! Indeed, life was fast ebbing away, and they felt that they must prepare me for the inevitable event, which was now a question of only a few short hours. As soon as I could arise from this stunning blow, I told Dr. Morrison that my husband must be informed of his condition. I well knew that death to him was but the opening of the gates of pearl into the inneffable glories of heaven; but I had heard him say that, although he was willing and ready to die at any moment that God might call him, still he would prefer to have a few hours’ preparation before entering into the presence of his Maker and Redeemer.

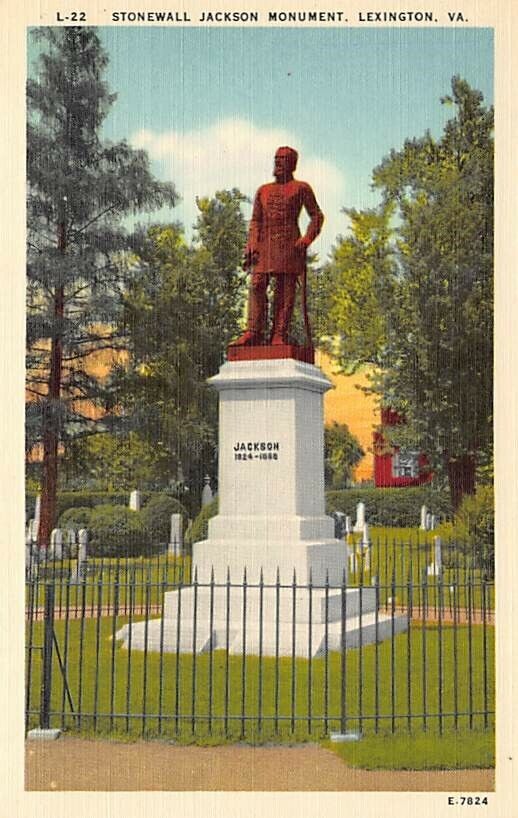

I therefore felt it to be my duty to gratify his desire. He now appeared to be fast sinking into unconsciousness, but he heard my voice and understood me better than others, and God gave me the strength and composure to hold a last sacred interview with him, in which I tried to impress upon him his situation, and learn his dying wishes. This was all the harder, because he had never, from the time that he first rallied from his wounds, thought he would die, and had expressed the belief that God still had work for him to do, and would raise him up to do it. When I told him the doctors thought he would soon be in heaven, he did not seem to comprehend it, and showed no surprise or concern. But upon repeating it, and asking him if he was willing for God to do with him according to His own will, he looked at me calmly and intelligently, and said, “Yes, I prefer it, I prefer it.” I then told him that before that day was over he would be with the blessed Saviour in His glory. With perfect distinctness and intelligence, he said, “I will be an infinite gainer to be translated.” I then asked him if it was his wish that I should return, with our infant, to my father’s home in North Carolina. He answered, “Yes, you have a kind, good father; but no one is so kind and good as your Heavenly Father.” He said he had many things to say to me, but he was then too weak. Preferring to know his own desire as to the place of his burial, I asked him the question, but his mind was now growing clouded again, and at first he replied, “Charlotte,” and afterwards “Charlottesville.” I then asked him if he did not wish to be buried in Lexington, and he answered at once, “Yes, Lexington, and in my own plot.” He had bought this plot himself, when our first child died, as a burial place for his family.

Mrs. Hoge now came in, bearing little Julia in her arms, with Hetty following, and although he had almost ceased to notice anything, as soon as they entered the door he looked up, his countenance brightened with delight, and he never smiled more sweetly as he exclaimed, “Little darling! sweet one!” She was seated on the bed by his side, and after watching her intently, with radiant smiles, for a few moments, he closed his eyes, as if in prayer. Though she was suffering the pangs of extreme hunger, from long absence from her mother, she seemed to forget her discomfort in the joy of seeing that loving face beam on her once more, and she looked at him and smiled as long as he continued to notice her. Tears were shed over that dying bed by strong men who were unused to weep, and it was touching to see the genuine grief of his servant, Jim, who nursed him faithfully to the end.

He now sank rapidly into unconsciousness, murmuring disconnected words occasionally, but all at once he spoke out very cheerfully and distinctly the beautiful sentence which has become immortal as his last: “Let us cross over the river, and rest under the shade of the trees.”

Was his soul wandering back in dreams to the river of his beloved Valley, the Shenandoah (the ‘river of sparkling waters ‘), whose verdant meads and groves he had redeemed from the invader, and across whose floods he had so often won his passage through the toils of battle? Or was he reaching forward across the River of Death, to the golden streets of the Celestial City, and the trees whose leaves are for the healing of the nations? It was to these that God was bringing him, through his last battle and victory; and under their shade he walks, with the blessed company of the redeemed.

General Jackson had expressed the desire, when in health, that he might enter into the rest that remains for God’s people on the Lord’s day. His wish was now gratified, and his Heavenly Father translated him from the toils and trials of earth, soon after the noon of as beautiful and perfect a May day as ever shed its splendor upon this world, to those realms of everlasting rest and bliss where

“Sabbaths have no end,

And the noontide of glory eternally reigns.”

Never shall I forget Mr. Lacy’s ministrations of consolation to my bleeding heart on that holiest of Sabbath afternoons. Seated by my bedside, he talked so of Heaven, giving such glowing descriptions of its blessedness, and following in imagination the ransomed, glorified spirit, through the gates into the city, that at last peace, the “peace of God,” came into my soul, and I felt that it was selfish to wish to bring back to this sorrowful earth, for my happiness, one who had made such a blissful exchange. But this frame of mind did not last, and many were the subsequent conflicts to attain and keep this spirit.

The remains were carefully prepared by the loving hands of the staff-officers, the body being embalmed and clothed in an ordinary dress, and then wrapped in a dark-blue military overcoat. His Confederate uniform had been cut almost to pieces by his attendants, in their endeavor to reach and bind up his wounds, on the night of his fall. Late in the evening I went into Mr. Chandler’s parlor to see all that was left of the one who had been to me the truest, tenderest, and dearest of all the relations of earth-the husband of whom I had been so proud, and for whom I thought no honors or distinctions too great; but above all this I prized and revered his exalted Christian character, and knew that God had now given him “a crown of righteousness.”

Yet how unspeakable and incalculable was his loss to me and that fatherless baby! Dead! in the meridian of his grand life, before he had attained the age of forty years! But “alive in Christ,” for evermore!

All traces of suffering had disappeared from the noble face, and, although somewhat emaciated, the expression was serene and elevated, and he looked far more natural than I had dared to hope.

That night, after a few hours’ sleep from sheer exhaustion, I awoke, when all in my chamber was perfect stillness, and the full moon poured a flood of light through the windows, glorious enough to lift my soul heavenwards; but oh! the agony and anguish of those silent midnight hours, when the terrible reality of my loss and the desolation of widowhood forced itself upon me, and took possession of my whole being! My unconscious little one lay sweetly sleeping by my side, and my kind friend, Mrs. Hoge, was near; but I strove not to awaken them, and all alone I stemmed the torrent of grief which seemed insupportable, until prayer to Him, who alone can comfort, again brought peace and quietness to my heart.

The next morning I went once more to see the remains, which were now in the casket, and were covered with spring flowers. His dear face was wreathed with the lovely lily of the valley-the emblem of humility-his own predominating grace, and it seemed to me no flowers could have been so appropriate for him. Since then, I never see a lily of the valley without its recalling the tenderest and most sacred associations.

On Monday morning began the sad journey to Richmond. A special car had been set apart for us, in which were Mr. Lacy and the staff-officers, while Mrs. Hoge and Mrs. Chandler were my attendants, and proved themselves the kindest of friends and comforters. Upon reaching the suburbs of the city, the train stopped, and we were met by Mrs. Governor Letcher and other ladies, with several carriages, and driven through the most retired streets to the governor’s mansion. Kind friends had also in readiness for me a mourning outfit. These were indeed most thoughtful considerations on their part, and could not have been more gratefully appreciated.

The funeral cortége then proceeded on its way into the city, and was followed for two miles by throngs of people.

Business had been suspended, and the whole city came forth to meet the dead chieftain. Amidst a solemn silence, only broken by the boom of the minuteguns and the wails of a military dirge, the coffin was borne into the governor’s gates, and hidden for a time from the eyes of the multitude, that were wet with tears.

The casket, enveloped in the Confederate flag, and laden with spring flowers, was placed in the centre of the reception-room in the Executive Mansion. It was here that I looked upon the face of my husband for the last time. No change had taken place, but, the coffin having been sealed, the beloved face could only be seen through the glass plate, which was disappointing and unsatisfactory. In honor of the dead, the next day a great civic and military procession took place. The body was carried through the main streets of the city, the pall-bearers being six major and brigadier generals, dressed in full uniform. The hearse, draped in mourning, and drawn by four white horses, was followed by his horse, led by a groom; next by his staff-officers; regiments of infantry and artillery; then a vast array of officials-the President, Cabinet, and all the general officers in Richmond-after whom came a multitude of dignitaries and citizens; and then all returned to the Capitol.

Every place of business was closed, and every avenue thronged with solemn and tearful spectators, while a silence more impressive than that of the Sabbath brooded over the whole town. When the hearse reached the steps of the Capitol, the pall-bearers, headed by General Longstreet, the great comrade of the departed, bore the corpse into the lower house of the Congress, where it was placed on a kind of altar, draped with snowy white, before the speaker’s chair. The coffin was still enfolded with the white, blue, and red of the Confederate flag.

The Congress of the Confederate States had a short time before adopted a design for their flag, and a large and elegant model had just been completed, the first ever made, which was intended to be unfurled from the roof of the Capitol. This flag the President had sent, as the gift of the country, to be the windingsheet of General Jackson.

During the remainder of the day the body lay in state, and was visited by fully twenty thousand persons-the women bringing flowers, until not only the bier was covered, but the table on which it rested overflowed with piles of these numerous tributes of affection.

At the hour appointed for closing the doors the multitude was still streaming in, and an old wounded soldier was seen pressing forward to take his last look at the face of his loved commander. He was told that he was too late-the casket was then being closed for the last time, and the order had been given to clear the hall. He still endeavored to advance, when one of the marshals threatened to arrest him if he did not obey orders. The old soldier hereupon lifted up the stump of his mutilated arm, and with tears streaming from his eyes, exclaimed: “By this arm which I lost for my country, I demand the privilege of seeing my general once more.” The kind heart of Governor Letcher was so touched by this appeal that at his intercession the old soldier’s petition was granted.

The tears which were dropped over his bier by strong men and gentle women were the most true and honorable tributes that could be paid him, and even little children were held up by their parents that they might reverently behold his face and stamp his name upon their memories.

While all these public demonstrations were taking place in the Capitol, how different was the scene in my darkened chamber, near by! A few loving friends came to mingle their tears with mine, among whom was my motherly friend, Mrs. William N. Page, and my eldest brother, Major W. W. Morrison, arrived that day from North Carolina. Both of these dear ones accompanied me on the remainder of the sad pilgrimage to Lexington. I also received a precious visit from the Rev. Dr. T. V. Moore, whom I had never met before, but his winning gentleness of face, his selections of the most comforting passages of Scripture- such as the 14th chapter of John, beginning, “Let not your heart be troubled; ye believe in God, believe also in me”-and his fervent, touching prayer could not have been more grateful and soothing proving balm, indeed, to my wounded, crushed heart. I never saw him again, but he, too, has long since joined that “army of the living God,”

“Part of whose host have crossed the flood, And part are crossing now.”

Little Julia was an object of great interest to her father’s friends and admirers, and so numerous were the requests to see her that Hetty, finding the child growing worried at so much notice and handling, sought a refuge beyond the reach of the crowd. She ensconced herself, with her little charge, close to the wall of the house, underneath my window in the back yard, and there I heard her crooning, and bewailing that “people would give her baby no rest.

On Wednesday morning we again set out on our protracted funeral journey, going by the way of Gordonsville to Lynchburg, and all along the route, at every station at which a stop was made, were assembled crowds of people, and many were the floral offerings handed in for the bier. His child was often called for, and, on several occasions, was handed in and out of the car windows to be kissed.

No stop was made at Lynchburg, but a vast throng was there to attest their interest and affection, and to present flowers. Here we took the canal-boat which was to convey us to Lexington, and on Thursday evening, with our precious burden, we reached the little village which had been so dear to him, and where his body was now to repose until “the last trump shall sound” and “this mortal shall have put on immortality.”

At Lexington our pastor, Dr. White, and our friends and neighbors met us in tears and sorrow. The remains were taken in charge by the corps of cadets of the Virginia Military Institute, and carried to the lecture-room where General Jackson, while professor, had taught for ten years, and were guarded during the night by his former pupils.

On Friday, May 15th, the body was again escorted by the officers and cadets of the Institute, together with the citizens, to the Presbyterian Church, in which he had so loved to worship, where the services were conducted in the simplest manner by the pastor and other visiting ministers. Conspicuous among these was General Jackson’s valued friend, Dr. Ramsey, of Lynchburg, who offered a prayer of wonderful pathos. The hymn “How blest the righteous when he dies!” was sung, after which Dr. White read the 15th chapter of I. Corinthians – that sublime description of the resurrection of Christ and of the believer; and then delivered an address, which was as just and appropriate as it was heartfelt and affecting. The casket, followed by a long procession of people, from far and near, was borne to the cemetery, and, with military honors, was at last committed to the grave.

The spot where he rests is “beautiful for situation”–the gentle eminence commanding the loveliest views of peaceful, picturesque valleys, beyond which, like faithful sentinels, rise the everlasting hills.

My pastor took me to his own home, and never could the loving-kindness and sympathy of true hearts be exceeded by that of himself, his family, and the good people of Lexington to me, in this hour of deepest affliction and bereavement. When the time came for my sad departure from my once happy, married home, the noble people of Virginia extended to me every kindness. I was provided with two escorts to convey me to my father’s home in North Carolina; one of General Jackson’s staff being detailed by the military authorities to attend me; and the Virginia Military Institute, wishing to do honor to the name of its late professor, also sent one of his colleagues upon the same mission. I mention these facts simply in token of gratitude, and realizing that these and all the tributes paid to my hero-husband are but evidences of the love and veneration in which his name and memory are enshrined in the hearts of his countrymen, and of the good and noble of all lands.

The depth of loss and emotion can be felt in every word. No true Southerner who values our history and remembers our Confederate ancestors can read it without tears.

And I do believe General Jackson crossed that river and is resting under those shade trees right now, forever in God’s holy presence.

A Christian warrior to the end, noble and true to his duty, never forgotten!

The death of Jackson was the death of my country. To read Mrs. Jackson’s words is to weep for them both.

The saying that behind every great man is a great woman could not have been more clearly proven than in the case of the Jacksons.

Any Southerner, by birth or at heart, has to visit Chancellorsville. Still featured, modestly maintained and interpreted, is the path that General Jackson and his staff travelled beyond their lines before turning to be met by friendly fire. Hardly more than 50 yards long, nearby is marked where Little Sorrel was caught after bolting at the volley. It’s difficult describing the feeling while standing in their paths.

The visitor center is very nice as they go, with informative exhibits and historical artifacts from early May, 1863. Interesting but possibly an afterthought to most is an encased artist’s diorama portraying General Jackson and his staff at the moment in the dark. The half-acre acre next to the building is the place though.

Hardly a half-hour drive away is the plantation office at Guinea Station, where Mrs. Jackson had to tell “Tom” he must die. It’s in, still, a quiet rural setting.

I was in tears reading this. I recently visited Chancellorsville and many other battlefields and other sites across the country. I saw the monument marking the place Jackson was wounded, and the room of the house he died in. I explored many of the places these great men fought.

Sincere sorrow borne of great love.

Lee’s anxious misery at the woeful news.

An army on its praying knees.

A city crushed worse than in defeat.

Emotion poured out vicariously on a tender child.

Death met with hope in justification thru faith in a risen Savior.

The eternal weight of Mrs. Jackson’s recollections more inspirational than stories of battlefield wins.

The greatest tragedy seeing how by 2024 the majority of people in the federal state of the victors had diverted sewage into the river that once gave spiritual vitality to their ancestors.

Great name for a great man and a great son.

First time reading this through tears of sorrow.

Stonewall Jackson will always be remembered in the Southland!

I will never forget my visit to Guinea Station many years ago on a lovely warm Sunday afternoon. I would never go back now because I know that the little building in which the great man died will have been “contextualized” and I couldn’t bear to see that.

It was fine last summer. No “slave trails”. No mention of any other than Gen. Jackson’s death vigil.

Nearby, too, Chancellorsville is hanging on. I posted a description above. The gift shop has a slave section and sells few Confederate flag trinkets but interpretation is battle and Jackson’s mortal wounding.

Thank you Gordon. I am going back for another visit. I am thankful Guinea Station has not been ruined. I also want to go back to Lee’s Stratford Hall, but I have been told it is pretty woke. Let’s hope that is not really the case.

I hope I haven’t steered you wrong. I should mention signs on I-95 no longer say, “Stonewall Jackson Shrine”. Rather, since 2019 it’s “Stonewall Jackson’s Place of Death”. An article online said there were complaints to the NPS with designation as a shrine. When I was there in July, however, I neither saw nor heard a discouraging word.

I’m going to inspect Stratford soon myself. I used to go once a year. The only explicit sign of worry I have is their literature and solicitations don’t mention Gen’l Lee. We’ll see. I want to see the Lee Chapel in Lexington too. I’ll call first to see if it’s still open to visitors. I checked in October and it was closed. We’ll see.