A newspaper in Chillicothe, Ohio, in 1887 and in 1902 stated that Sally Hemings’ last child, slave Eston Hemings, resembled Thomas Jefferson. Just how that resemblance was established is unclear. Eston Hemings died in 1877; Thomas Jefferson, in 1826. So, the newspaper was reporting that one person that had been dead for 10/25 years resembled another that has been dead for 61/86 years. Those in Chillicothe in 1887 and 1902 had never seen Thomas Jefferson. Upon what did they base their claims?

There is more ravelment. The resemblance, we know, was based on a statue of Thomas Jefferson (2) in Washington, D.C., that was commissioned by French sculptor Pierre-Jean David D’Angers in 1834 and was based on Thomas Sully’s 1821 painting of Jefferson (1) That statue[1] was said to resemble Eston by a group of men who had travelled to Washington, seen the statue, returned to Ohio and asked Eston about his resemblance to the statue. Eston merely replied that his mother belonged to Jefferson and that “she was never married.”[2]

Upon inspection of Sully’s painting of Jefferson, late in life, one sees clearly how the statue is based on the painting. Yet Sully’s 1821 painting is far from his best representations. Sully was, at times, an extraordinary painter; at other times, perhaps somewhat cavalier, perhaps hasty. Bodily proportions—e.g., the head is undersized—are off. Moreover, D’Angers sculpture depicts a youthful, robust Jefferson, so he took liberties with Sully’s painting, though it differs posturally only inasmuch as the right arm is erect, not relaxed. Jefferson, who subsisted mostly on a diet of vegetables, was never a stout man.

And so, we have a judgment that Eston Hemings resembled a three-dimensional statue of Jefferson, based on a two-dimensional painting of Jefferson that is of questionable likeness. Rumora volat!

All of that bespeaks the question: Just what did Jefferson look like?

From what I know, Jefferson was reticent about using his cell phone to take “selfies.” He just was not that vain, so we have no snapshots of the man. Thus, we must rely on written descriptions of him and depictions of him by sketchers, painters, and sculptors.

I begin with selected written accounts of Jefferson.

Pre-Presidential

Marquis de Chastellux (1782): “Let me then describe to you a man, not yet forty, tall, and with a mild and pleasing countenance, but whose mind and attainments could serve in lieu of all outward graces. … I at first found his manner grave and even cold; but I had no sooner spent two hours with him than I felt as if we had spent our whole lives together.”

William Maclay (1790): “Jefferson is a slender man; has rather the air of stiffness in his manner; his clothes seem too small for him; he sits in a lounging manner, on one hip commonly, and with one of his shoulders elevated much above the other; his face has a sunny aspect; his whole figure has a loose, shackling air.”

La Rochefoucault-Liancourt (1796): “In private life Mr. Jefferson displays a mild, easy and obliging temper, though he is somewhat cold and reserved.”

Samuel Harrison Smith (1801): “The stature of Jefferson was lofty and erect; his motions flexible and easy; neither remarkable for, nor deficient in grace; and such were his strength and agility that he was accustomed in the society of children … to practise feats that few could imitate.”

Presidential

William Plumer (1802): “a tall, highboned man”

Edmund Bacon (overseer form 1806–1822): “Mr. Jefferson was six feet two and a half inches high, well proportioned, and straight as a gun barrel. He was like a fine horse—he had no surplus flesh. … His countenance was always mild and pleasant.”

Sir Augustus John Foster (1807): “Jefferson … was … very tall in body and affected to despise dress. … His appearance being very much like that of a tall large-boned farmer.”

Frances Few (1808): “he is a tall thin man not very dignified in his appearance … his face is short and his nose and chin approach each other—his teeth are good he shews but little of them when he laughs—he stoops very much but holds his head high.”

William Wirt (longtime young friend): “a strong and sprightly step … the tall, and animated, and stately figure.”

Post-Presidential

Francis Calley Gray (1815): “He is quite tall, six feet, one or two inches, face streaked and specked with red, light grey eyes, white hair, dressed in shows of very thin soft leather with pointed toes and heels ascending a peak behind with very short quarters, grey worsted stocking, corduroy small clothes, blue waistcoat and a coat, of stiff thick cloth made of the wool of his own merinoes and badly manufactured, the buttons of his coat and small clothes of hornlon, and an under waistcoat flannel bound with red velvet. His figure bony, long and with broad shoulders, a true Virginian.”

Francis Hall (1816): “I found Mr. Jefferson tall in person, but stooping and lean with old age, thus exhibiting that fortunate mode of bodily decay, which strips the frame of its most cumbersome parts, leaving it still strength of muscle and activity of limb.”

George Flower (1816): “Mr. Jefferson’s figure was rather majestic: tall over six feet, thin, and rather high-shouldered; manners, simple, kind, and courteous. His dress, in color and form, was quaint and old-fashioned, plain and neat—a dark pepper-and-salt coat, cut in the old quaker fashion, with a single row of large metal buttons, knee-breeches, gray-worsted stockings, shoes fastened by large metal buckles.”

Isaac Briggs (1820): “His 77th year finds him strong, active, and in full possession of a sound mind. He rides a trotting horse and sits on him as straight as a young man.”

Adam Hodgson (1820): “Mr. Jefferson’s appearance is rather prepossessing. He is tall and very thin, a little bent with age.”

Reverend S.A. Bumstead (1822): “his hair is quite thick … his features regular. … He was remarkably erect and had every appearance of antiquity about him.”

D.P. Thompson (1822): “Mr. Jefferson—a tall, straight, sandy-complexioned man.”

Alexander H.H. Stuart (1823): “raw boned man, with rather large hands.”

While some of the descriptions seem contradictory—he was both stiff and loose—I think there is a consistent picture we get through the years. Jefferson was tall, bony, and thin. His complexion was sandy and with rosacea. He was stiff, even shacklingly so, in formal settings, but loose, even stooping, in informal ones, but ungraceful, or at least not graceful, in all setting, and of the habit of conservative informality of dress. He was reserved and cool in all settings, until one made his acquaintance.

Let us now look at selected depictions of him by contemporary artists.

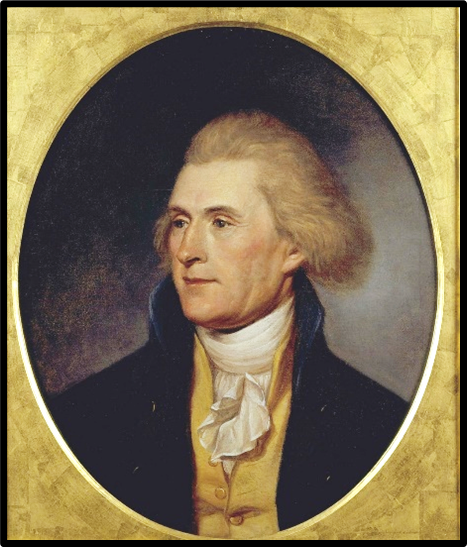

First, there is John Trumbull’s miniature of Jefferson (3), created late in the 1780s. Trumbull made three miniatures of Jefferson from his small painting Declaration of Independence. We have a young, confident man, with wavy, sandy-red hair, light complexion, exaggeratedly long neck, and ruddy cheeks.

There is, roughly at the same time, Mather Brown’s Jefferson (4), created in 1786. With powdered wig, Jefferson sits, almost in the exact manner of Trumbull’s Jefferson, and stares blankly, almost lifelessly, into space. Of this painting, Jefferson’s secretary, William Short, said to Trumbull (10 Sept. 1788) that it was “an étude [as] it has no feature like him,” except perhaps for a long neck.

In 1791, Charles Willson Peale paints Jefferson (5), as secretary of state in Washinton’s administration. Jefferson is 48 at the time. The flowing hair reminds us of Trumbull’s early painting. The eyes are not so deeply set as those in Rembrandt Peale’s two paintings (7 and 8). The neck again is long and the eyes are dark, but the eyes are friendlier than those in Trumbull’s painting.

In 1805, Gilbert Stuart crafted on paper with watercolor and crayon and what has come to be called “Medallion Portrait” (7). Painter and sculptor Rett Longmore thought that this was superbly done and quite likely an excellent depiction of Jefferson. Granddaughter Ellen Randolph Coolidge confirms Longmore’s assessment. She says, in a letter to sister Virginia Randolph Trist (13 May 1828), that the depiction is an “incomparable portrait, and the only likeness ever taken of him I think that gives a good idea of the original.”

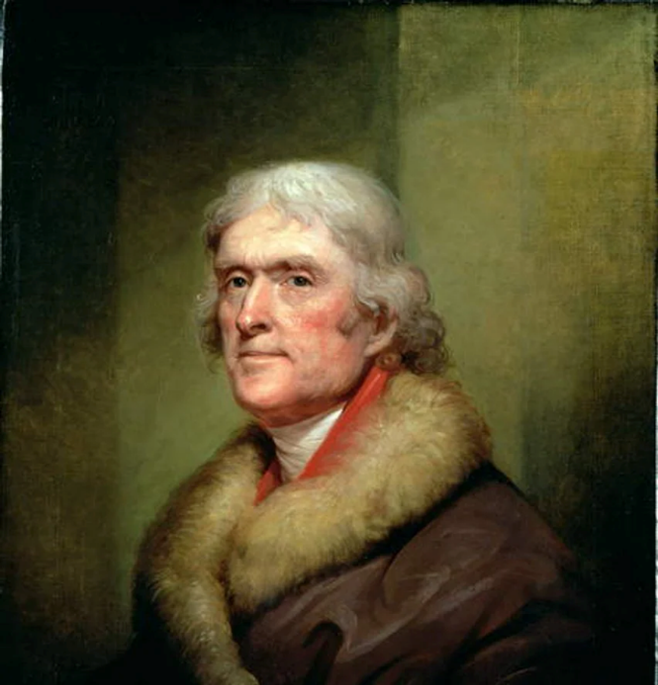

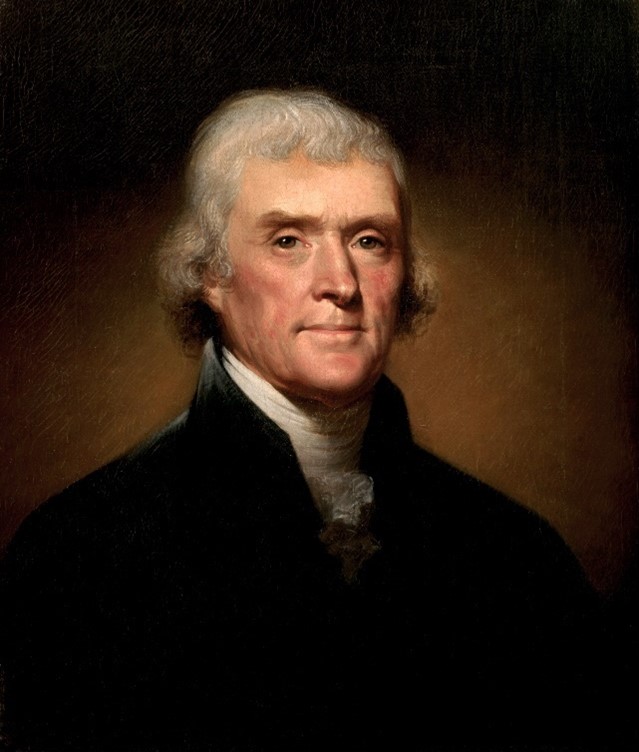

In the same year, Rembrandt Peale has Jefferson sit for him. Peale’s work is masterful (7). There is extraordinary detail in the fur of Jefferson’s leathered jacket as well as in Jefferson’s face, matured. The eyes are penetrating and dark, inconsistent Grey’s 1815 assertion that Jefferson had grey eyes. Peale makes creative use of chiaroscuro—use of light and shade on what is perhaps drapery in the rear to draw us, through use of a light-green diagonal, to the face of Jefferson, which is serious, intelligent, and confident, but not uninviting. There are numerous facial minutiae (e.g., rosacea and wrinkles) that this small rendering of the painting fails to capture.

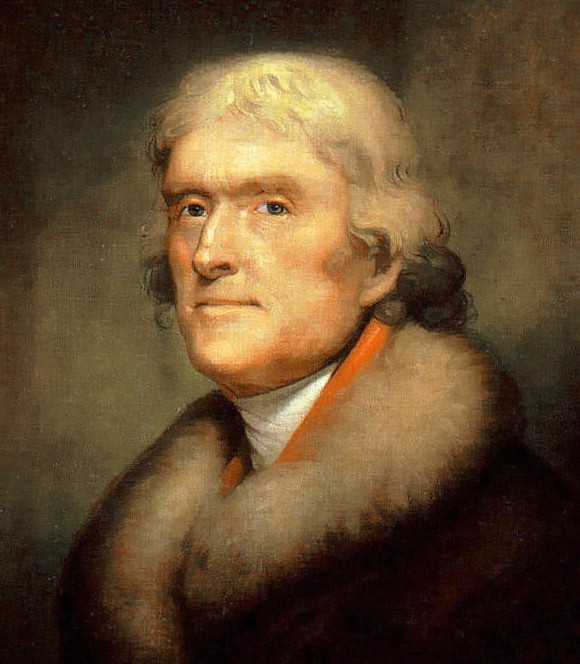

It is illustrative to compare Peale’s painting of 1805 with his painting of Jefferson in 1800 (8). This earlier version is very dark and viewers cannot help but be drawn to Jefferson’s face, given by Peale magnificent detail and which shows large wisdom. The eyes engage viewers and the lips, slightly pursed, are warm.

Finally, I turn to a marble bust and bronze statue of Jefferson.

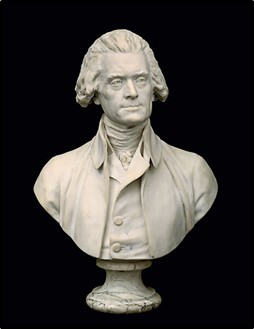

The first is by Parisian sculptor, Jean Antoine Houdon, in 1785, while Jefferson was in Paris. Houdon was perhaps the world’s foremost sculpturer at the time. Houdon (9) depicts in marble a long-necked Jefferson, dressed as an American statesman and with penetrating eyes, hirsute brows, and hair, flowing back in the manner of Trumbull’s and C.W. Peale’s paintings. This Jefferson, certainly idealized, is over-serious and all business.

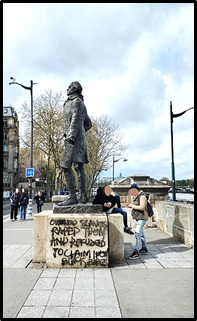

I end with a statue of Jefferson by Jean Cardot in Paris (10). He was minister plenipotentiary from 1784 to 1789. It is a thin, confident Jefferson, captured in bronze and 10 feet in length by Cardot in 2006, who holds in his hand a draft of his Declaration and who is far-gazing, suggestive of a vision for liberty that is applicable to all men, everywhere. Wokeism, however, has too reached Paris, as the base has been effaced by ignorant #@$%&! morons with the words: “Owned slaves, raped them, and refused to claim his black babies.”

What can we conclude from artists’ depictions of Jefferson?

Jefferson was a confident, serious man, though not offputtingly so. His eyes are typically shown to be dark, which is largely inconsistent with persons lightly complected and with thick, sandy-ruddy hair that was early on combed back. Darkness might be artistic license to illustrate Jefferson as visionary. His neck in most depictions is overly long, but that might be again artistic liberty to accentuate Jefferson’s face and Jefferson’s high intelligence. Close inspection of most of the paintings suggests that Jefferson might have had a lazy eye.

I also interviewed a professional artist for his interpretation of what Jefferson really looked like.

********************************************

[1] It was in New York City Hall till it was removed in 2021, because of Jefferson’s avowed racism.

[2] That is, according to Gordon-Reed and Onuf, how the rumor of concubinage began. Annette Gordon-Reed and Peter S. Onuf, “Most Blessed of the Patriarchs”: Thomas Jefferson and the Empire of the Imagination (New York: Liveright Publishing, 2016), 16.

Interesting article! I personally own a canvas print of Peale’s 1800 portrait of Jefferson as well as a small resin replica of Houdon’s bust. Wonderful representations of a great human being.

As an aside, the vandalism of Jefferson’s statue in Paris strikes me as particularly odd. Not the vandalism itself, which is predictable in today’s irreverent culture, nor the fact that a supposed Frenchman elected to scrawl his vandalism in English, but the phrasing of the words themselves, specifically the use of the word “babies” as opposed to “children,” “kids,” or another somewhat more general word. Call me crazy, but my Yankee senses are tingling. I would not be the least bit surprised if the vandalism was the work of an expatriate American.

Thank you. I agree about the vandal likely being American.