William Byrd II of Westover on the James River in Colonial Virginia lived a full generation before Thomas Jefferson, but they are comparable in their intellectual pursuits. Byrd had perhaps the largest library in the colonies, certainly below the Potomac River, and he began each day by reading, usually ancient authors, Greek or Roman, in the original languages. Private diaries of Byrd, written in code, were found 2 centuries after his death and have been deciphered and published in 2 separate books, the first with daily entries from 1709 to 1712, and the second from 1739 to 1741.

A typical entry, this one from October 19, 1710, begins, “I rose at 6 o’clock and read a chapter in Hebrew and some Greek in Homer. I said my prayers and ate boiled milk for breakfast. I settled accounts with several people. About 11 o’clock I went to court…” Another on March 12, 1712, begins, “I rose about 7 o’clock and read a little Latin in Horace. I said my prayers and ate chocolate for breakfast…” Thirty years later, the entries became more succinct, but his pattern of reading upon rising remained. On April 2, 1740, he began simply, “I rose about 6, read Hebrew and Greek. I prayed and had tea…” In virtually every entry of his diaries he touches upon the ancients.

This appreciation for the classics persisted in the South for about 2 centuries, perhaps until Pearl Harbor in 1941, when the South began its blend with the rest of the country. With the emphasis on learning the classics, also came a reverence for antiquity and the past in general, the canon of the Classical-Christian Western Civilization. In contrast, educators in the North tended to emphasis theology and a discontinuity with the past. This Southern emphasis on classical learning was evident in the curriculum of Emory College in Oxford, Georgia, right up to the Civil War, and beyond, perhaps until Pearl Harbor.

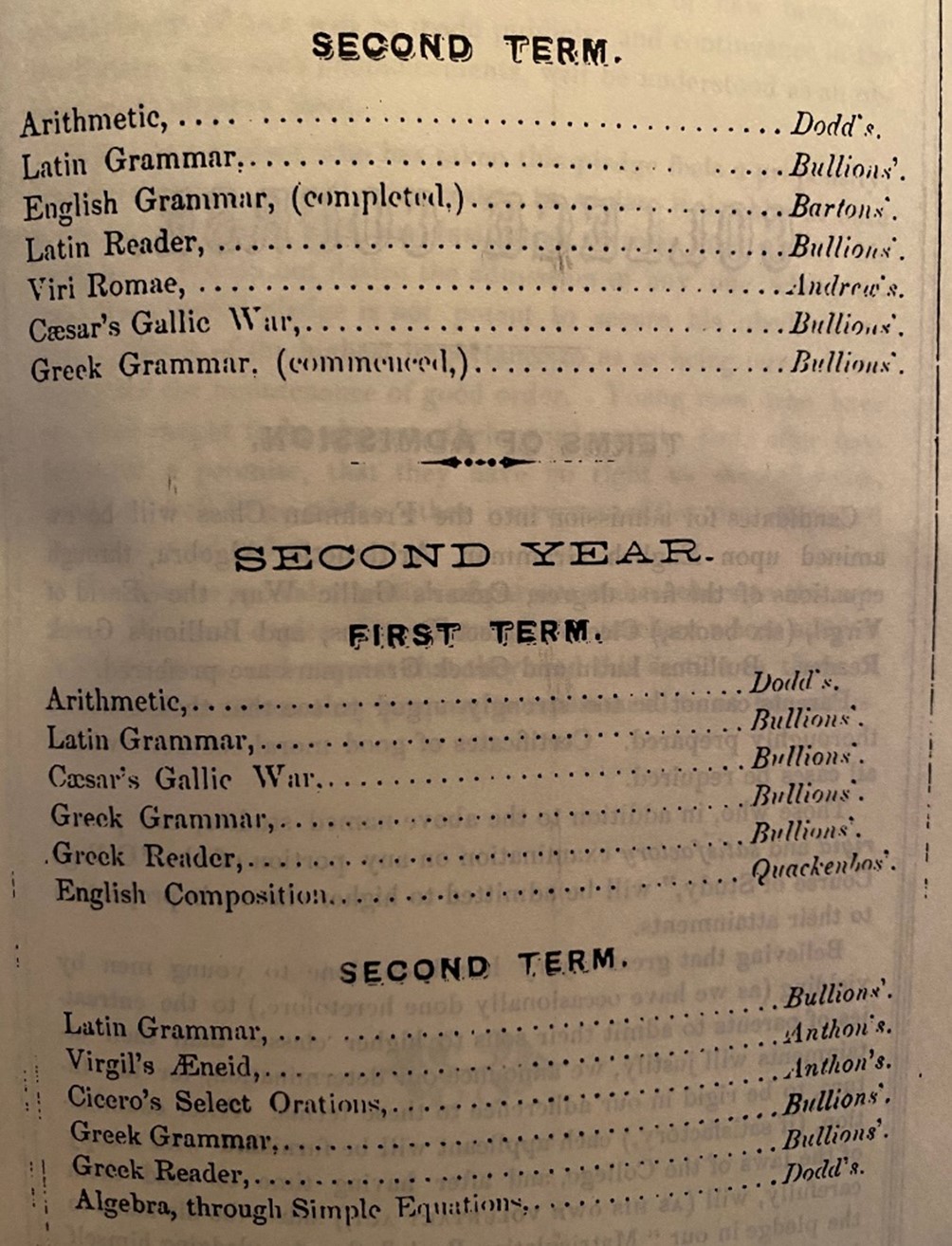

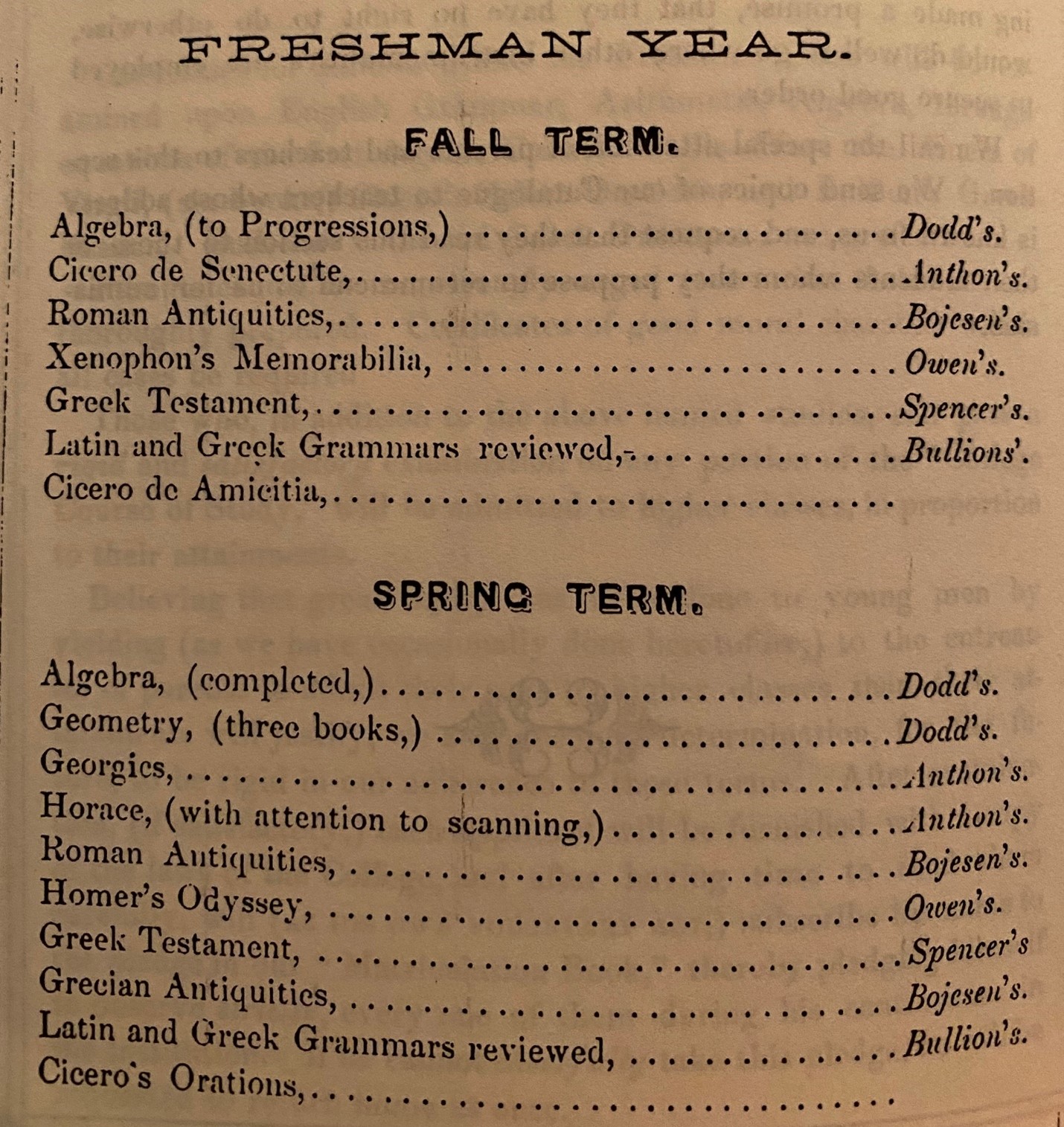

Emory College had 2-year Preparatory Academy meant to prepare a Southern boys for the college curriculum. In 1860 there were 95 students enrolled in the Academy. Joseph Spencer Stewart, 34 years old, himself a graduate of Emory College, was the Principal, and the curriculum of those 2 years of study is as follows:

In the first term there is a course on Latin Grammar and a Latin Reader. By the 4th term, 5 courses deal with the Ancients, their language and writings, and Algebra was added. The intent is obviously preparation for college, and the Freshman Year at Emory College continues the emphasis on the classics, including Cicero’s Orations:

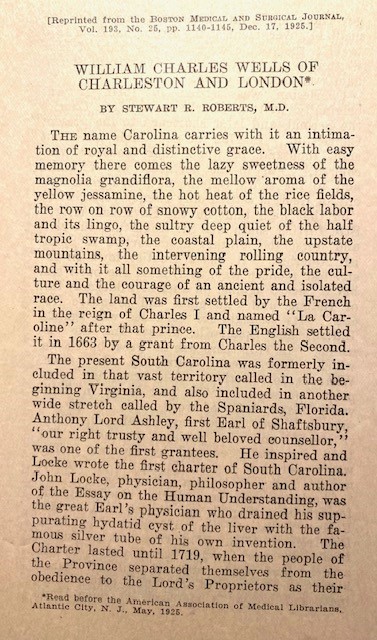

Stewart R. Roberts, MD [1878-1941], my grandfather, graduated from Emory College at Oxford in 1902 with 1st honors. He was the last of my ancestors to study the classics in a structured curriculum. My father graduated from SMU in 1954 and did not. I graduated from Vanderbilt in 1981 and did not. We both majored in English, but the Classical and Christian tradition was not built into our college curriculum, as it was for my grandfather at Emory at the turn into the 20th century.

The writings of my grandfather (a hundred published papers and a book on pellagra), in my opinion, reflect this different education, which is now absent in our Southern colleges. I would like to submit two samples of his prose to illustrate this foundation. He was often called, “The Osler of the South,” after Sir William Osler the great Canadian physician, and he was also the first cardiologist in the South. These two samples come from addresses, both in 1925:

My father was a very good writer and a prolific one, but his prose (and mine) is so radically different than his father’s. I cannot explain it, except to suggest that the education of Stewart R. Roberts, built on a foundation of classical writings and the Bible, was different. The prose seems deeper and richer than modern writing. The modern mind, even in the South, no longer interprets the world in the same way.

A very interesting article. I have often wondered about the difference in both style and content that only reading in translations compared to the original language must have on the impression left by the author on the reader.