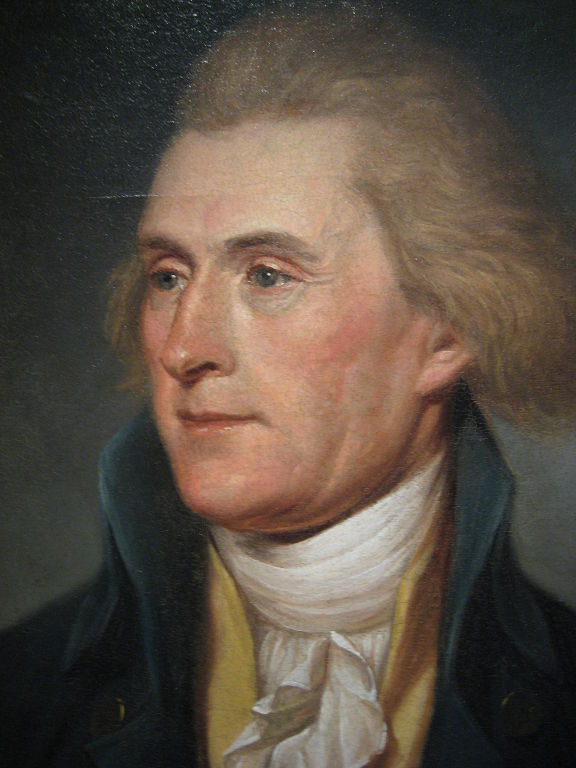

After a lengthy respite due to tensions between the two that began during Adams’ presidency, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, with the intervention of Benjamin Rush, resumed their correspondence with a brief letter from Adams to Jefferson on January 1, 1812.

On June 15, 1813, Jefferson aims to clear the air, as it were. He brings up partisan differences concerning “the improvability of the human mind, in science, in ethics, in government.” Jefferson continues:

altho’ in the passage of your answer alluded to, you expressly disclaim the wish to influence the freedom of enquiry, you predict that that will produce nothing more worthy of transmission to posterity, than the principles, institutions, & systems of education recieved from their ancestors.

Adams replies toward the end of a letter on June 25.

Checks and Ballances, Jefferson, however you and your Party may have ridiculed them, are our only Security, for the progress of Mind, as well as the Security of Body.

Adams’ somewhat oblique rejoinder refers to arguments that he gives in his two political books, Discourses on Davila and his Defense of the Constitutions of the Government of the United States of America. Any group of people will gladly persecute another for the sake of power and fame, and that applies to religious groups as well as political groups.

Jefferson, in a letter on June 27, states that there is a fundamental disagreement between people, divided into two camps, concerning the best rule of societies: rule of the people or rule of the aristoi. That disagreement has existed, adds Jefferson, from the beginning of social living.

On June 28, July 9, July 13, July 15, Aug. 14, Sept. 2, and Sept. 15, Adams pens letters to Jefferson on his view on the natural aristoi. For instance, on Sept. 2, he writes:

Now, my Friend, who are the aristoi? Philosophy may Answer “The Wise and Good.” But the World, Mankind, have by their practice always answered, “the rich the beautiful and well born.” And Philosophers themselves in marrying their Children prefer the rich[,] the handsome and the well descended to the wise and good.

Adams continues:

The five Pillars of Aristocracy, are Beauty Wealth, Birth, Genius and Virtues. Any one of the three first, can at any time over bear any one or both of the two last.

The argument in each letter is the same: an appeal to experience.

- Good birth and wealth have together ever prevailed over virtue and talent [in all social matters, political included].

- So, good birth and wealth will ever prevail over virtue and talent [in all social matters] (1).

- So, there cannot be any workable political system without inclusion men of good birth and wealth (2).

The number and length of Adams’ many letters, expressing the same argument through different historical illustrations on natural aristoi, is indicative of frustration, ire, and urgency on this philosophical theme. Adams, I suspect, is eager to hear that Jefferson has been flummoxed into philosophical submission. Adams has argued so thoroughly and cogently that Jefferson can disagree only by being recalcitrant: by refusing to be logical.

During Adams’ flurry of letters, Jefferson writes only one letter to Adams (Aug. 22) and in it he does not address the issue of Adams’ notion of natural aristocracy.

It is not until October 12 that Jefferson lifts his quill and answers Adams’ impatient letters:

I agree with you that there is a natural aristocracy among men. the grounds of this are virtue & talents. formerly bodily powers gave place among the aristoi. but since the invention of gunpowder has armed the weak as well as the strong with missile death, bodily strength, like beauty, good humor, politeness and other accomplishments, has become but an auxiliary ground of distinction.

there is also an artificial aristocracy founded on wealth and birth, without either virtue or talents; for with these it would belong to the first class. the natural aristocracy I consider as the most precious gift of nature, for the instruction, the trusts, and government of society. and indeed it would have been inconsistent in creation to have formed man for the social state, and not to have provided virtue and wisdom enough to manage the concerns of the society.

Jefferson expresses a view antithetical to Adams’. Jefferson’s natural aristoi concerns men of virtue and talents (intelligence and ambition). Adams’ natural aristoi is not natural, but artificial. In effect, Jefferson blocks Adams’ argument from the history of mankind, the first part of which is of the form:

- Humans have ever believed p.

- So, humans will ever believe p (1).

We can see the fallacious nature of this form of inductive argument by plugging in “that the sun moves around the earth” or “that war is inevasible” for p.

Men of wealth and birth, adds Jefferson, without possession of virtue and talents are large hindrances to good governing. The best government is that which does what it can to debar the artificial aristoi from all governmental offices. In sum, Jefferson not only disagrees with Adams, he says that actualization of Adams’ views would lead to the worst possible government.

Thomas Jefferson here is certainly responding to Adams’ description of his natural aristoi in his two books, greatly misunderstood and unjustly maligned, as Adams habitually claims.

Yet the malignity is not unjust and Adams’ views are not misunderstood. They are merely incoherent.

Adams is clear that all men are driven by passion, not reason. Forms of government—monarchy, aristocracy, or democracy—and religion and education “are, singly, totally inadequate to the business of restraining the passions of men, of preserving a steady government, and protecting the lives, liberties and properties of the people.” He sums, “Religion, superstition, oaths, education, laws, all give way before passions, interest, and power, which can be resisted only by passions, interest, and power.”[1] In sum, the large passions, interest, and power of the natural aristoi need to be checked by those of the executive and the elected representatives of the people, otherwise the natural aristoi will prove to be the ruin of social order. What if the passions, interest, and power, certainly lesser, of those two bodies are ill-directed? How is there to be anything, on such an account, but tohubohu, but chaos? If the natural aristoi need to be checked from above and from below and if they are superior in capacities to both of the checking powers, what guarantee is there that the checking powers will check rightly or even have any capacity to check? Moreover, how can the check of one passion upon another passion lead to amelioration of the human condition and progress?

Adams states of the problem of corralling the power of the rich and wealthy to conduce to social betterment:

The only remedy is to throw the rich and the proud into one [political] group, in a separate assembly, and there tie their hands; if you give them scope with the people at large, … they will destroy all equality and liberty, with the consent and acclimations of the people themselves. They will have much more power, mixed with the representatives than separated from them. If they unite, they will give the law, and govern all; if they differ, they will divide the state, and go to a decision by force.[2]

The solution is to group the natural aristoi (in a senate) and to check their strong passions from above and from below, and they too will be a check on the passions of the executive of above and of the elected representatives of below—hence, Adams’ notion of checks and balances in his letter of June 25, 1813.

The argument is illogical. The nodus I illustrate by an analogy. Imagine an inordinately powerful ox, owned by an eighteenth-century farmer. The power of the ox is so great that he has the ability to work a number of fields in a time that it would take eight oxen to work in the same period of time. The farmer, having purchased the ox, drools at the possibilities. Yet the ox has no desire to work fields. He instead wishes to eat and to eat much, to lounge often, and when restive, perhaps to knock down a few sheds, and perhaps even the farmer’s barn or even his house.

Jefferson, in contrast to Adams, wishes the power of government to be in the hands of the citizenry, meetly and generally educated. What guarantees have we that the citizenry will govern well and wisely?

All persons are born with a moral sense that directs human activities for the best, unless there are albatrosses. Sketched out:

- Humans are by nature morality-sensitive creatures.

- Humans are naturally inclined to be morality-abiding, unless there are artificial obstructions.

- Political obstructions that favor the artificial aristoi impede moral actions.

- Jeffersonian republicanism—government of and for the people through elected representatives, inter alia—is a political philosophy that is workable only if all such obstacles are removed.

- So, Jeffersonian republicanism allows for unobstructed activity of moral agents (1–4).

- A government that allows for unobstructed activity of moral agents is the best form of government.

- So, Jeffersonian republicanism is the best form of government (6).

The difficulty of Jefferson’s argument is the dubiousness of premise 1. If it is false, or if there is some reason to doubt humans’ general desire to work toward social wellbeing, Jefferson republicanism will not work.

And so, we find in the disagreement between Adams and Jefferson on the natural aristoi the fundamental political differences that inform Adamsian Federalism and Jeffersonian Republicanism.

Enjoy the video on the subject below….

*****************************

[1] John Adams, Defense of the Constitutions of Government of the United States of America, 323–24.

[2] John Adams, Defense of the Constitutions, 183.

The problem isn’t rule by an ‘artificial aristoi’ of Adamsian Federalism or rule by a ‘natural aristoi’ of Jeffersonian Republicanism; the fundamental problem with government is ‘rulership’ itself! The sordid and arrogant belief that some people have that they can direct and control the lives and actions and even the beliefs and thoughts of individuals other than themselves. And that they have not just the right to do so but the ability to do so. This perverse belief is not only utterly fallacious but a pathological, egomaniacal and a self-indulgent expression of rampant hubris. Until it is ultimately and finally rejected; the chaos, corruption and injustice resulting from it will continue.

“Liberty, then, is the sovereignty of the individual, and never shall man know liberty until each and every individual is acknowledged to be the only legitimate sovereign of his or her person, time, and property, each living and acting at his own cost.”

— Josiah Warren

There will never be a really free and enlightened State until the State comes to recognize the individual as a higher and independent power, from which all its own power and authority are derived, and treats him accordingly. I please myself with imagining a State at last which can afford to be just to all men, and to treat the individual with respect as a neighbor; which even would not think it inconsistent with its own repose if a few went to live aloof from it, not meddling with it, nor embraced by it, who fulfilled all the duties of neighbors and fellow-men. A State which bore this kind of fruit, and suffered it to drop off as fast as it ripened, would prepare the way for a still more perfect and glorious State, which also I have imagined, but not yet anywhere seen.

– Henry David Thoreau, “Civil Disobedience” [1849]

True RR, but one must consider how entrenched was that view for many centuries. The notion of equality that we take for granted was held by few at the time.