John Rutledge was born in Charleston, South Carolina, in September, 1739. His father, Dr. John Rutledge, was a native of Ireland, who emigrated to South Carolina in 1735. He married Sarah Hext, a lady of liberal endowments and cultivation, who became the mother of the future jurist in the fifteenth year of her age. She was left a widow at twenty-six, with seven small children, two of whom, John and Edward, became men of great distinction.

John Rutledge was favored with the instructions of Rev. Mr. Andrews, an English clergyman and a successful teacher, under whom he pursued classical and other studies for several years. In the summer of 1755, a few months before arriving at the age of seventeen, he left school and entered upon the study of law with James Parsons, a barrister of distinction at the colonial bar, and at the time of his death, which occurred in 1779, Vice-President of South Carolina. Rutledge continued in the office of Mr. Parsons for two years, and then proceeding to London, he entered as a student in the Inner Temple. He remained there three years, during which great expectations were formed of him. The letters of his fellow students to their friends at home spoke of his talents in terms of admiration. He returned home to engage in the practice of his profession in 1761. Even before his arrival in Charleston, he received flattering proof of the reputation that had preceded him. While the vessel in which he was returning was eight or ten miles below the town, a gentleman, who was defendant in a suit for breach of promise which was coming on for trial, went down in a pilot-boat to meet him and engage him for his advocate. In this case, Rutledge displayed so much ability and eloquence as to astonish all who heard him. He obtained a verdict for his client and received a hundred guineas for his fee. He gave the whole purse to his mother, whose self-denial and economy, cheerfully practiced for her children, deserved, as it received, their lasting gratitude. Rutledge was not compelled, as are most lawyers, to rise by tedious steps to a prominent place in his profession, but suddenly found himself a leader at the bar with all the business he desired. He was employed in the most difficult cases and retained with the largest fees.

Two years after being called to the bar, Rutledge was married to Miss Elizabeth Grimké, a union from which he derived unalloyed happiness. He was ardently attached to his wife, and her death, which occurred in 1792, was one of the causes of the malady which clouded the evening of his life. In 1764, he was appointed pro tempore Attorney General of the Province, and performed the duties of that position until June, 1765. His practice was interrupted by the stirring political events in which he figured preliminary to the Revolution.

In 1764, Governor Boone refused to administer to Christopher Gadsden the oaths which the law required every person returned as a member of the Legislative Assembly to take before he entered upon his duties. This aroused the indignation of the House, as being a violation of their constitutional privileges as the sole judges of the qualifications of their own members. By his courageous and eloquent speeches, Rutledge did much to excite the Assembly and the people to resist such encroachments of the royal governors, thus fanning the spark which became the great revolutionary conflagration of a few years later.

The passage of the Stamp-Act, called forth a proposition from the Assembly of Massachusetts to the different Provincial Assemblies for appointing committees to meet in congress as a rallying point of union. Many objections were made to this novel project in South Carolina, but they all vanished before the eloquence of John Rutledge. A vote for appointing deputies was carried in South Carolina before the proposition was accepted by the neighboring provinces. John Rutledge was appointed one of the deputies to the first Congress, which, in 1765, assembled in New York. Although one of the youngest members of that body, his distinguished abilities attracted marked attention and gave him great influence.

A few years followed in which Mr. Rutledge was no further engaged in politics than as a lawyer and a member of the provincial legislature. But, in 1774, a more extensive field was opened before him. He was appointed a delegate to the Continental Congress. When the members of the Convention were considering with great difference of opinion what instructions they should give their delegates, John Rutledge brought forward a motion to give no instructions whatever, and advocated it in a most eloquent speech. He demonstrated that anything less than plenary discretion in the delegates would be unequal to the crisis. To those who stated the dangers of such extensive powers, and begged to be informed what must be done in case the delegates made bad use of their authority to pledge the State to any extent, Rutledge answered: “Ilang them.” The proposition so vigorously supported was triumphantly carried. Furnished with such ample powers, the delegates from South Carolina took their seats in Congress under great advantages, and by their conduct justified the confidence reposed in them.

The people of South Carolina established a new constitution on the 26th of March, 1776, and in conformity with its provisions, Rutledge was elected president and commander in chief of the State. He applied himself at once to the work of organizing the new government and in preparing for defense against an expected invasion by the British. When General Lee, who commanded the continental troops, was disposed to give orders for the evacuation of Sullivan’s Island, Governor Rutledge directed that it should be held, at all hazards. He wrote to General Moultrie, who commanded on the island: “You will not evacuate the fort without an order from me; I would sooner cut off my hand than write one.” This brave determination, which resulted in saving an important stronghold, proved to be a most important service to the patriot cause.

Mr. Rutledge resigned the presidency of South Carolina in March, 1778, after an efficient service of two years. In February, 1779, he was recalled to the executive office, but under a new constitution and with the name of Governor, substituted for that of President. His utmost zeal and energy were required to meet the extraordinary emergencies growing out of the invasion by the British. He fully met the public expectation, and at the close of his executive service, in 1782, both the Senate and House of Representatives expressed in emphatic language the grateful sense they entertained of his unwearied zeal and attention to the interests and welfare of the State.

In January, 1782, Mr. Rutledge was elected a delegate to Congress, and took his seat in that body on the second of May. The surrender of Cornwallis in the preceding autumn had impressed the people that the war was over, so that they were no longer disposed to act with suitable vigor. Fearing that this languor would encourage Great Britain to recommence the war, Congress sent deputations of their members to rouse the States to a sense of their danger and duty. John Rutledge and George Clymer were sent in this capacity to the Southern States. They went to Virginia and made a personal address to the Assembly of that State. Rutledge drew such a picture of the situation, and the danger to which the country was exposed by the backwardness of particular States to comply with the requisitions of Congress, as produced a very happy effect.

Soon after the termination of his congressional services, Mr. Rutledge was appointed Minister Plenipotentiary from the United States to Holland, but declined serving. In 1784, he was elected a Judge of the Court of Chancery, in South Carolina. He drew the bill for organizing it on a new plan, and in it introduced several new provisions which have been very highly commended as improvements on the English Court of the same name.

In 1787, he was a member of the Federal Convention, which framed the Constitution of the United States. As soon as it went into operation, he was designated by President Washington as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, and was immediately confirmed by the Senate. The first term of the Supreme Court was held in New York, in February, 1790, but Rutledge was not present. On the 16th of February, 1791, he was elected by the Legislature, Chief Justice of the Court of Common Pleas of South Carolina. He accepted the office and resigned his seat in the Supreme Court of the United States.

Upon the resignation of Chief Justice Jay, President Washington appointed Rutledge to the vacant post, his commission dating July 1, 1795. About that time Jay’s treaty reached Rutledge and stirred his deepest indignation. He denounced it in violent terms, thus calling forth the eager approbation of the enemies of the administration and the indignation of its friends. Rutledge sailed for Philadelphia on the 31st of July, and was present at the August term of the Supreme Court. Of his judicial bearing while presiding at this term of the Supreme Court, Mr. Wharton says: “Enough has come down to enable us to say that though tinged with that haughtiness which in later years had marked him, it was graceful and courtly, and that his natural impetuosity had been subdued by the approach of age, the weight of long public service, and the anxiety of a position which he could not but regard as too insecure.” On the adjournment of the Supreme Court, after a session of a few days, the Chief Justice returned to Charleston. It became evident that his intellect was disordered. When Congress met in December, the Senate refused to confirm his appointment. This act, which was the dictate of prudence, “extinguished the last spark of sanity and closed his public career.” The remnant of his life is a blank and a void. It was passed in the fluctuations of a disease which prostrated alike mind and body. He languished, with brief intervals of convalescence, until the 18th of July, 1800, when his death occurred “the wearing out of an exhausted frame rather than the result of positive illness.”

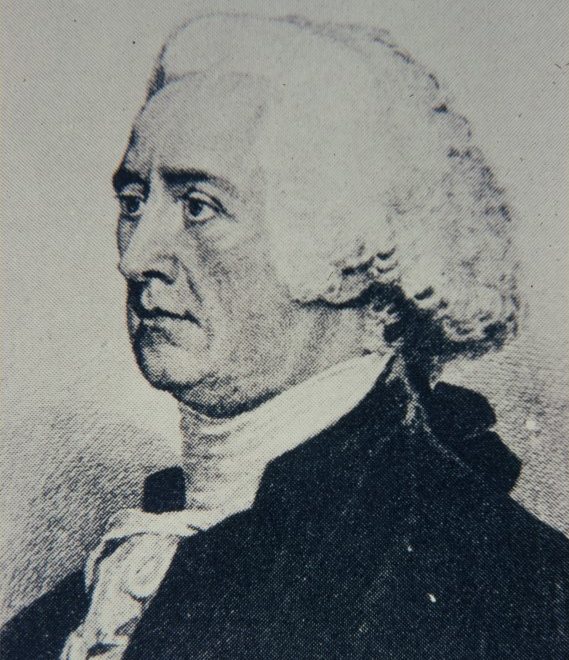

The portrait of Rutledge by Trumbull, an engraving of which accompanies this sketch, is said to give an accurate idea of his personal appearance. “He was tall, his frame well formed and robust. His forehead was broad and full; his eyes dark and piercing. His mouth was compressed, and together with the lower part of his face indicated firmness and decision. His hair was combed back from his forehead, and according to the fashion of the times was powdered and tied behind. His aspect was resolute-almost stern, and was an expression of blended thought and determination.”

It has been well said of Rutledge by one of his biographers that “the high position he held in the opinion of contemporaries was the result of qualities equally high and rare. Though his feelings were warm and ardent they seldom controlled his judgment. Vigorous common sense, and an impulsive energy that forthwith executed its dictates, were his greatest excellencies as a public man. He had nothing in common with that class of politicians who are governed by metaphysical niceties and logical distinctions, unrepressed and uncorrected by broad views and extensive generalizations. He saw things in their practical relations, and formed his judgment accordingly. He had one quality which, even unallied with high abilities, will always have great weight in the affairs of mankind–he was always in earnest. His opinions were not suspended in doubt, nor his inspirations and original impulses neutralized and confounded by refined speculations. Energetic and ardent he pressed forward to his objects with unfailing and unfaltering resolution. Earnestness was the characteristic of his eloquence and the secret of its power.”

Nevertheless, Rutledge was by no means a perfect character. He has been described as “proud and haughty, imperious in manner, hasty and obstinate in temper, and as not entirely exempt from those frailties which social customs in his day tolerated, if it did not encourage.” Yet he undoubtedly deserves to be ranked among the very ablest and greatest of the revolutionary leaders. He was eminent as an orator, a legislator and a jurist. He possessed administrative talents of the first order. He was a man of tireless action, intense energy, and exhaustless fertility of resource. possessed the qualities of decision and firmness in a remarkable degree, and was endowed with an indomitable will. He possessed the firmest physical courage, manifested by intrepidity in the midst of danger. He possessed the higher and rarer trait of moral courage. He feared not to incur a responsibility, or boldly avow an unpopular principle. He scorned alike to conceal an opinion and to abandon a principle. Beyond most men of his time, he was free from the restraints of party, maintaining unfettered independence of thought, word and action.

Thanks for sharing this wonderful piece of history.