Thomas H. Landess walked among Giants. He wrote and talked about them too. It was April of 1968, and he had gathered a few at the University of Dallas for a reunion under the banner of the Southern Literary Festival. It was a reunion of the surviving Southern Agrarians—Andrew Lytle, John Crowe Ransom, Allen Tate, and Robert Penn Warren—Lyle Lanier couldn’t make it, and Donald Davidson, too ill to attend, passed away mere days later. Landess and Louise Cowan were at the helm of the conversations, some of which included M.E. Bradford and Thomas Daniel Young. The intention to publish these talks never materialized. Recordings and transcripts of the event still exist, stored in the cold sterility of Vanderbilt’s archives.[1]

The fall of 1980 was a time when America, as usual, was consumed with a blend of politics and nonsense. Reagan and Carter were out on the hustings while the country held its collective breath awaiting the outcome of a fictional shooting on television. Meanwhile, three Giants remained. They made their way to Nashville. Robert Penn Warren, Lyle Lanier, and Andrew Lytle returned to the very place where it had all begun—Vanderbilt University. The occasion was the Symposium on I’ll Take My Stand, Fifty Years After.

I’ll Take My Stand argued that the South must shun the siren allure of industrialism if it were to maintain its traditional culture. Art, religion, and a sense of community could be nurtured only in a society where men lived close to the soil. Combining a primitive love of nature with an aristocratic disdain for commerce, the Agrarians were ridiculed—or simply ignored—by self-respecting progressives on both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line. – Mark Royden Winchell[2]

The years between 1950 and 1979 saw the gradual erosion of the Twelve’s ranks. John Gould Fletcher chose oblivion in 1950. His weapon of choice—a shallow cattle pond. Henry Blue Kline’s body turned against him in ‘51. Frank Owsley’s heart faltered after their ‘56 gathering. Stark Young and John Donald Wade bowed out in ‘63, while H.C. Nixon held on until ‘67. Donald Davidson lasted to ‘68, and John Crowe Ransom fell in ‘74. On a cold February day in 1979, Allen Tate slipped away from this world, his light extinguished by those cigarettes he’d clung to like old memories.

Walter Sullivan and William C. Havard were convinced Vanderbilt should mark the golden anniversary of I’ll Take My Stand. The university’s embrace of the Agrarian reunion wasn’t a sure thing. The South had changed, its soil tilled by new ideas, and many saw the Fugitive-Agrarian legacy as a withered crop best forgotten, Vanderbilt included, especially the English department’s new guard. Sullivan had already faced pushback when he tried to bring Cleanth Brooks back after his retirement from Yale. Even Allen Tate’s papers had been rejected by the university and sold to Princeton for $70,000.

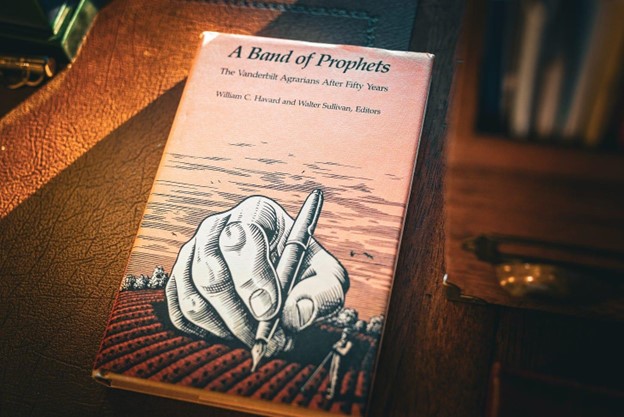

Yet, in the end, from October 30th to November 1st, they gathered at Vanderbilt to discuss the Agrarian legacy. Charles P. Roland, John Shelton Reed, Lewis P. Simpson, Robert B. Heilman, and Louis D. Rubin, Jr. read their papers; M.E. Bradford, Louise Cowan, and Virginia Rock responded to them; and Cleanth Brooks—in one of his rare returns to Vanderbilt—moderated a panel with Lanier, Lytle, and Warren. Unlike the 1968 Dallas reunion, this symposium produced a book, A Band of Prophets: The Vanderbilt Agrarians After Fifty Years. Edited, with an Introduction by William C. Havard and Walter Sullivan. Louisiana State University Press, 1982. But that’s not the book I’m here to talk about.[3]

I’m here regarding a book—one Professor Sullivan carried with him to the festivities above—a paperback I’ll Take My Stand, published by LSU Press in 1980. But before that, before we talk about the book, we must speak of the man. Like Mr. Landess, Walter Sullivan walked with Giants.

In his controversial memoir Making It, Norman Podhoretz characterizes the several generations of writers associated with the Partisan Review as “The Family.” It should be dear by now that modem Southern literature is also a multi-generational family, with its share of filial loyalties and sibling rivalries. The Vanderbilt branch of that family came into being with the birth of John Crowe Ransom in 1888 and Donald Davidson in 1893. The major figures of the second generation (Tate, Lytle, Brooks, and Warren) first saw the light of day between 1899 and 1906. Thus Walter Sullivan, who was born in 1924, is one of the youngest members of the third generation. As such, he is too young to have been a part of the Southern Renascence but old enough to feel that he missed out on something important. Those facts go a long way toward explaining Sullivan’s sense of himself as a writer and critic of fiction. – Mark Royden Winchell[4]

Walter Sullivan came into the world on January 4, 1924, in Nashville, Tennessee. His father was gone before the boy could even speak his name. He was raised by his mother, her kin, and his daddy’s folks. He entered Vanderbilt University in 1941, but like many of his generation and the generation of his professors, war called him away. The War, though, spared him the full brunt of its horror, and by 1947, Sullivan had returned home and graduated from Vanderbilt. His path led to Iowa, where under the mentorship of Andrew Lytle, and alongside classmates like Flannery O’Connor, Sullivan deepened his craft. By 1949, his M.F.A. in hand, he returned to Vanderbilt, where he remained until his retirement in 2000.

Sullivan’s first two novels, Sojourn of a Stranger (1957) and The Long, Long Love, took place in Middle Tennessee. His stories and essays appeared in Modern Age and many of the Southern journals, quarterlies, and reviews. In the 1970s, he hosted Between the Lines, a Nashville TV show on literature, and I need to find it. He married, raised children, and found faith, eventually settling into the Roman Catholic Church. His death came on August 15, 2006, in the city of his birth.

He studied under Lytle, Richmond Croom Beatty, Donald Davidson, Walter Clyde Curry, and Claude Finney. He became friends with some of his professors and many others illustrated by those he acknowledged in his memoir Nothing Gold Can Stay (University of Missouri Press, 2006): Louis Rubin Jr., Lewis P. Simpson, George Core, George Garrett, Joe Blotner, Elizabeth Spencer, Wendell Berry, Shelby Foote, Madison Jones, Fred Chappell, Cleanth Brooks, Peter Taylor, Walker Percy, Robert Penn Warren, Allen Tate, Andrew Lytle, Donald Davidson, Donald Davie, Robert Lowell, and on and on.[5]

Latecomer

for Walter Sullivan

He stands outside unwontedly alone.

The door muffling the ebullient social natter

Of voices he’s known forever: Lon

And Mr. Ransom, Jean’s bright, unnerving chatter.

And Allen, of course there’s Allen, and Davidson

And Peter, Cal and Cleanth, Caroline

And chuckling Red. He names them one by one.

Auld lang syne. Eternity’s auld lang syne.

The talk is fugal music whose themes he knows

Thoughts of a literary renaissance.

Intricacies of intellectual lives.

He enters, takes his accustomed place, and bows

To the pleased party his genial recognizance—

But will wait his toddy until Jane arrives.

—Fred Chappell

The Book

Like I said, I’m here about a book. On my shelf sits a copy of I’ll Take My Stand, the one by the Twelve Southerners. It’s a paperback reissue of the 1977 edition. It includes introductions by Louis D. Rubin Jr. and biographical essays by Virginia Rock, material carried over from both the 1962 and 1930 editions. The book bears the marks of Giants—signatures, inscriptions, words of friendship and respect penned to Sullivan and his wife Jane.

Inscribed By The Following:

Louis D. Rubin Jr.: “For Jane & Walter- The Holy Writ”

Robert Penn Warren: “To Jane & Walter ever Red”

Andrew Lytle: “Walter and especially Jane – 1980”

Ward Allen: “With love”

John Shelton Reed: “With thanks and best wishes to the Sullivans”

Mary [?] (help me solve the mystery): “To our dearest friends with thanks for making this possible”

Signed By The Following:

Virginia J. Rock, M. E. Bradford, Cleanth Brooks, Brainard “Lon” Cheney, Lyle Lanier, Charles P. Roland, V. Jacque Voegeli, Lewis P. Simpson, and George Core. I’ve mentioned several of these names in previous essays.

How to Build a Library

Pluck Jack Burden’s web that Nashville fall, and you’d shake a world of books that reverberate through time like Murph’s bookcase. Pick a name, any name I’ve mentioned. Give it a tap and stand back. Watch how one life tumbles into the next like dominoes. One life touches a thousand others. Each touch a link. That’s where you’ll find the books. A Band of Prophets isn’t the only book on my shelves linked to I’ll Take My Stand’s 50th. I could show you hundreds.

****************************

[1] Fugitive Agrarians by Thomas H. Landess (Abbeville Institute).

The Southern Agrarians: Some Personal Recollections by Thomas H. Landess (Abbeville Institute).

Southern Scholarship vs. Neo-Conservatism: M.E. Bradford and the National Endowment for the Humanities by Thomas H. Landess (Abbeville Institute).

Agrarian Reunion Collection.

[2] Southern Quarterly 21.3, 1983, pp. 79-80.

[3] My main source for the 50th Anniversary event is Mark Royden Winchell’s Cleanth Brooks and the Rise of Modern Criticism. University Press of Virginia, 1996. Link to the event NEH Grant. Link to reviews of A Band of Prophets and Newspaper Clippings of the Vanderbilt Symposium.

[4] Hollins Critic 27.1, 1990.

[5] Sullivan bio sources: link, link. Chappell poem is from Place in American Fiction: Excursions and Explorations, edited by H. L. Weatherby and George Core. University of Missouri Press, 2004.

Excellent piece of work Mr. Chase Steely! What a treasure to have all of those signatures in one book.

I came across a song by Lynyrd Skynyrd called “I’ll I Can Do Is Write About It” I’m not sure if Ronnie Van Zant or any other members of the iconic Southern Rock band heard of the 12 Southerners, but their songs are proof the the South lives inside of us. Here is a part of the song that the Twelve Southerners warned the agrarian South what going to happen.

“I’m not tryin’ to put down no big cities

But the things they write about us is just a bore

Well you can take a boy out of ol’ dixieland

But you’ll never take ol’ Dixie from a boy

And lord I can’t make any changes

All I can do is write ’em in a song

I can see the concrete slowly creepin’

Lord take me and mine before that comes

‘Cause I can see the concrete slowly creepin’ “