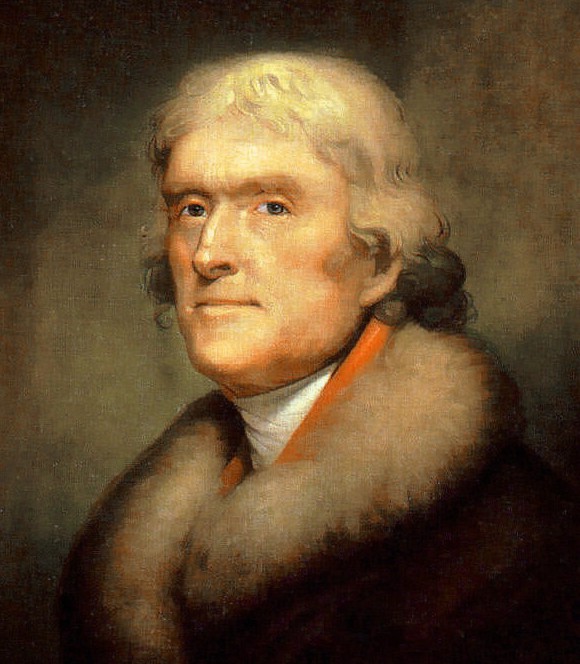

A Review of Garrett Ward Sheldon’s The Political Philosophy of Thomas Jefferson (Johns Hopkins, 1993) by Garret Ward Sheldon

In his preface to The Political Philosophy of Thomas Jefferson, political theorist Garrett Ward Sheldon articulates a modest, but significant aim for beginning his book, and he does so economically: in one paragraph. Sheldon takes seriously the notion of Jefferson as a political philosopher. “[My book] does not presume to provide a final word on the subject,” which is a task impossible for any scholar. It instead aims to offer insights into Jefferson’s mind that “will provide a starting point for further studies, by clearing the way through certain dilemmas of current early American historiography” (ix). That is the sort of modesty characteristic of clean scholarship that is today missing. Everyone aims to have the final word on Jefferson and in doing so each says much the same things as all others.

There are nine chapters to the book, and each chapter follows sequaciously the previous chapter. There is flow to the book.

Sheldon begins with the debated concerning Lockean Liberal and Classical-Republican interpretations of Jefferson’s political thinking. Sheldon shows that the debate is a false dilemma. The influence of both on Jefferson is profound: Locke is especially notable early in Jefferson’s writings (e.g., the Declaration); the Classical Republican tradition, in later writings. An adherent of political liberalism, Jefferson never adopted the relativistic moral psychology and contractual (Hobbesian) relativistic notion of justice of liberal atomism. As Jefferson notes to Francis Gilmer (7 June 1816), man was “created with a sense of justice” (57). Consequently, while each man is by nature endowed with certain rights to seek his own path to happiness, he is also by nature endowed with a sense of fellowship—that is, his moral sense, which inclines him to virtuous activity, which essentially involves other humans. Thus, Sheldon eschews, and rightly so, the axiological problem of Jefferson founding his political philosophy on the primacy of the individual (liberalism) or on the primacy of the state (republicanism). The notion of individuals without a state, for Jefferson, is meaningless. So to is the notion of a state without individuals.

Sheldon includes much discussion on the importance of humans’ moral-sense faculty in a chapter titled “Ethics and Democracy.” He correctly states that Jefferson’s ethical views blend ancient thinking with Christian morality. The ancients falter in noting merely our duties to ourselves, as they relate to personal tranquility. Christian ethics adds the social element: our duties to others or “universal philanthropy” (103–6).

There is one nodus with Sheldon’s view of Jefferson’s moral sense. He adopts an Aristotelian view of Jefferson’s moral sense. Sheldon says that the moral sense includes “knowledge and choice of the good, sympathy for other’s sufferings, and concern for the well-being of society generally” and constitutes “a public sense of virtue” (60); and elsewhere, “his innate sympathies and a capacity for moral reasoning” (144). Aristotle in Book IV of Nicomachean Ethics states that virtuous activity consists in (1) knowing that something is the right thing to do, (2) choosing that something, and (3) a settled virtuous disposition (i.e., infrequently doing the right thing does not make one virtuous). Yet for Jefferson, morality does not include knowledge and likely does not involve reasoning or choosing in any important sense. The moral sense is a sensory faculty. We sense or feel the right thing to do, and we are inclined to act on that feeling, if nothing, like reason or habituation over time to slothfulness, intervenes.[1]

Sheldon also notes the critical role for education in Jefferson’s political philosophy. “For Jefferson, an ‘ignorant democracy’ was a contradiction in terms” (65), and given the nested layers of governments—from lowest to highest: wards, counties, states, and the federal government—education must accommodate the needs of individuals at various levels. Through the process, “worth and genius,” not wealth and birth, are to be selected, and education throughout is to encourage political participation (62–65). Advances in learning—e.g., new scientific disclosures—demand periodical constitutional renewal (84). There is unfortunately no significant discussion by Sheldon of generational sovereignty, which I maintain is one of the axioms of Jefferson’s political philosophy.

What does Sheldon say of Jefferson on religious education?

Sheldon here mentions that for Jefferson the varied religious sects are chiefly corruptions to the teachings of Jesus. He barred a chair of divinity at University of Virginia only because “a single Chair of Divinity would imply representation of only one denomination” to the exclusion of all others (109). That is correct, but there is more to the story, as I have frequently noted. Jefferson’s view of sectarian religions, being corruptions of Jesus’ teachings, was hostile. He thought little of sectarianism, even though he befriended ministers of several sects. Although Jefferson succumbed to outside pressure to allow all denominations to use space at his university available for religious instruction, he often stated that religion was a personal, not a private, matter: a matter between a man and his deity. It is also noteworthy that in letters to intimates Jefferson frequently did not capitalize “god,” suggestive of a creator impervious to the supplications of humans—that is, an impersonal deity.[2]

To encourage political participation, government needed to be structured to inspire economic independence. Thus, Jefferson proposed riddance of entails and primogeniture, argued for relatively equal distribution of Virginian property (in his proposed constitution), and promoted American agriculture to encourage distribution of wealth and economical independence (72–78), without which there could be no equality and independence.

Sheldon in chapter 8 covers the “shadow of slavery” over Jefferson’s philosophical thinking. Sheldon recounts Jefferson’s views on Blacks in Query XIV of Notes on Virginia (128–34). His outline of Jefferson’s view of Blacks’ inferiority of intellection and imagination is accurate, but Sheldon unfortunately fails to include Jefferson cautionary and empirically grounded caveat that further investigation by naturalists might show his own conclusions to be ungrounded. In short, Jefferson believed in Blacks’ inferiority, but he also believed that his belief might be wrong.

Sheldon also notes that Jefferson was consistently against slavery, though he acknowledges that Jefferson could have done more to end the institution. “In Jefferson’s hierarchy of values, the emancipation of sleaves occupied a lower position than either his personal lifestyle or the ideal republic for which he had risked his life and fortune.” I agree with the second disjunct, but not with the first. If Jefferson’s personal lifestyle was so central to his daily activities, if he was so self-centered, he would not have spend most of his years serving the interests of others—his community, his state, his country, and the world through his interest in science.

The book ends with a short but informative chapter on freedom, democracy, equality, and rights. There is the puzzling claim in the penultimate paragraph of the chapter that Jefferson, as a political philosopher, was both “a pure materialist” and “an absolute idealist” (147). Is that a metaphysical or political assertion? If it is to be taken metaphysically, it is false. Jefferson is clear that he was a metaphysical materialist, not a metaphysical idealist. If it is to be taken politically, it asserts that Jefferson often saw things as they might be, but what are we to make of “pure materialist”? Is it someone who sees political events, reducible to minute material (atomic) movements, unfolding according to necessity? Sheldon could here be clearer, as we are so near to the book’s end, and that claim is meant to be a weighty claim.

The final chapter, overall, functions as a fine summary of the argument throughout the book, whose conclusion is that Jefferson’s political philosophy was “an original and distinctly American political theory” (147). That is a very large claim, but one that I think is true. Sheldon argues throughout his book persuasively for it.

In sum, Sheldon’s book is one of the few lucid works on the philosophical dimension of Jefferson’s cavernous mind.

I end by stating that it is not merely worthwhile reading for scholars and Jeffersonian mavens, but ought to be required reading.

Below, the interview with Dr. Garrett Ward Sheldon…. Enjoy!

*********************************

[1] See my book, Thomas Jefferson, Moralist.

[2] See my book The Surprisingly Simple Religious Views of Thomas Jefferson.

later in jeffersons life, i assume there were existing laws in the other states of who could enter, did he mention at any point of why he may not have worked harder to undo slavery with just seeing ‘writing on the wall’….the states surrounding the south weren’t going to permit many slave or free blacks and land for slaves to even buy in the south was scarce….as in already owned by families of whites often with large families? anything to that affect?

Scott:

I gave a talk on that topic for Abbeville at its last conference in GA.

He simply thought that the time was not right–that there could be more ill than good done by freeing slaves before the people wanted it done. It would also be a very costly project.

SEE: https://www.abbevilleinstitute.org/could-jefferson-have-done-more-to-end-slavery/

thanks…i watch it.