The Enlightenment was an epoch of unbridled optimism—a break from centuries of often blind reliancy on authority, and the sources of authority were generally the Bible and the works of Aristotle. With the shift to understanding the universe through empirical investigation of it (Gr., empeiria = experience), reliancy on authority weakened. Science—in the sense of strict observation of the world, hypotheses framed on those observations, and further tests of those hypotheses—was birthed.

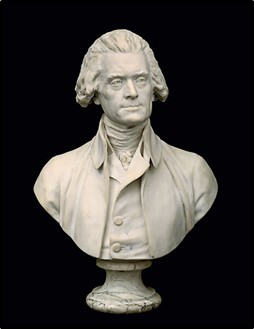

Jefferson it is commonly known was a practicing scientist of some repute, but more of a patron than a practitioner of science. In a letter to Benjamin Rush (15 Jan. 1811), he called Francis Bacon, John Locke, and Isaac Newton, all empiricists, the “trinity of the three greatest men the world had ever produced.” Francis Bacon described four idols—tribe, cave, marketplace, and theater—that kept men in darkness, and in doing so, he set the stage for a break with the sophistries of the past. Locke—writing on topics such as religious tolerance, epistemology, property, liberty, value, money, natural law, political philosophy, and education—was an empiricist of unquestioned breadth and depth. Newton broke the Aristotelian teleological mold with his discovery of the three laws of bodily motion and the universal law of gravity. Consequently, by identifying Bacon, Locke, and Newton as the three greatest men ever to have lived, Jefferson shows his commitment to settling matters from politics to physics by an appeal to experience.

The prevalent sentiment behind empiricism is that the cosmos is knowable not through appeal to reason, unchecked by experience, but through reason, confirmed by experience. The prevalent mode of scientific investigation was to observe, record, analyze, and then hypothesize. Then, even the staunchest hypotheses, unharmed by observation, were susceptible to future evidence, inconsistent with them.

The Enlightenment was a time of large men, and large optimism. There were discoveries in the natural sciences—e.g., Boyle’s Law concerning pressure and volume in a closed containers (P ≈ 1/V); Galileo’s Law of Falling Bodies (d ≈ t2); Newton’s law of universal gravitation (F ≈ Mm/r2) and his three laws of bodily motion; Kepler’s three laws of planetary motion; the extinction of species; observations of comets, supernovae, and the moons of Jupiter—and brilliant inventions that eased or promised to ease the burden of daily human existence—e.g., agricultural machinery and innovations, the telescope and microscope, the submarine, the balloon, and the spinning Jenny.

Enlightenment optimism manifest itself in the belief that, with the break from authority, continued and indefinite human improvement was inevitable. In the words of Condorcet in his History of the Progress of the Human Mind, “The perfectibility of man is absolutely indefinite.” That was a sentiment prevalent among Enlightenment thinkers such as James Harrington, Adam Smith, Francis Hutcheson, Adam Ferguson, Denis Diderot, Voltaire, Louis-Sébastien Mercier, Francois Quesnay, Benjamin Rush, Adam Weishaupt, and Immanuel Kant. The aim was truth, and the catalyst for truth was liberty. Authority could monopolize its version of “truth” only because it had for centuries burked liberty.

Like other large men of his day, Jefferson freely breathed the air of liberty and he believed progress toward truth was inevasible. Science was inexorably on the march. “When I contemplate the immense advances in science and discoveries in the arts which have been made within the period of my life,’ says Jefferson to Benjamin Waterhouse (3 Mar. 1818), “I look forward with confidence to equal advances by the present generation, and have no doubt they will consequently be as much wiser than we have been as we than our fathers were, and they than the burners of witches.” There could and would be glitches—“truth and reason … will eternally prevail,” writes Jefferson to Rev. Knox (12 Feb. 1810), “however, in times and places they may be overborne for a while by violence—military, civil, or ecclesiastical”—but given the embrace of liberty, truth would surface, perhaps slowly, but certainly.

There were political truths and moral truths for Jefferson. Jefferson writes to Lafayette (26 Dec. 1820), “The disease of liberty is catching; those armies will take it in the south, carry it thence to their own country, spread there the infection of revolution and representative government, and raise its people from the prone condition of brutes to the erect altitude of man.” Representative government, a sort of compromise of aristocratic and democratic governments, was not merely an alternative, but a better form of government, because it was more in keeping with human nature, and humans were by nature equal and free. As Jefferson writes in his own draft of the Declaration of Independence, “We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with inherent and inalienable rights; that among these, are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” Thus, republican government was a better form of government because it was morality-grounded and it was essentially government of and for the people.

If liberty was the catalyst for truth, then governmental interposition in citizens’ affairs was its enemy, and governmental interposition usually took the form of governmental sanction of falsehood. Says Jefferson in his Notes on the State of Virginia: “It is error alone which needs the support of government. Truth can stand by itself.” Yet error is itself relatively harmless. When put to the test of “free argument and debate,” then “errors ceas[e] to be dangerous,” says Jefferson in his 1779 Bill for Religious Freedom, It is harmful only when given governmental sanction.

To Judge John Tyler (8 June 1804), Jefferson writes of the 1798 assault on truth and liberty with the Alien and Sedition Acts. “Man may be governed by reason and truth.” Thus, “all avenues to truth” must be left open, and so the presses must be free. He continues, “I hold it, therefore, certain, that to open the doors of truth, and to fortify the habit of testing everything by reason, are the most effectual manacles we can rivet on the hands of our successors to prevent their manacling the people with their own consent.” Liberty and the free exercise of reason are essential for prosperous government.

Jefferson firmly believed in veridical exchanges with others. He writes to nephew Peter Carr (19 Aug. 1785): “It is of great importance to set a resolution, not to be shaken, never to tell an untruth. There is no vice so mean, so pitiful, so contemptible; and he who permits himself to tell a lie once, finds it much easier to do it a second and a third time, till at length it becomes habitual; he tells lies without attending to it, and truths without the world’s believing him. This falsehood of the tongue leads to that of the heart, and in time depraves all its good dispositions.” Thus, a falsehood, uttered once as a conveniency can readily lead to maleficent habits, and ultimately to malevolency.

Finally, there is for Jefferson truth in education. Jefferson’s University of Virginia was for him to be a proving ground for the principles of republican governing—liberty, reason, and truth being foremost among them. He writes to William Roscoe (27 Dec. 1820), “Here [at UVa] we are not afraid to follow truth wherever it may lead, nor to tolerate any error so long as reason is left free to combat it.”

Things are much different today. We are nowadays flippant about truth, but not about liberty. We still tend to believe that liberty of some sort is the natural human state, but we are indifferent to truth, and the reason for indifferency is that we staunchly maintain that one man’s truth is as good as any others’. Why? Liberty pace Jefferson and other Enlightenment thinkers has become an end, not a means. For Jefferson, liberty was never an end, but always a means. The end, in the realm of science, was truth; in the realm of morality, human happiness.

We have lost sight of the coupling of liberty and truth, even though we live in a time when we are making more discoveries of the way the world works—e.g., DNA sequencing, other planets, and life-saving or life-preserving medicines—than there have ever been. Freedom for the sake of freedom, as Plato noted millennia ago, is a debilitating ideal. It gives license for each person to do whatever he wishes to do. That was not Jefferson’s conception of liberty. Each citizen was free to order his life in whatever way he pleased, but each was also expected to participate in affairs of government to his fullest extent, and government, in partnership with science, would be forward-looking, not treadmill or backward-leaning. Liberty without truth is a false god. We would do well to learn from Jefferson and other progressive Enlightenment thinkers.

Enjoy part 2 of our interview with Professor Garrett Ward Sheldon¸ UVA¸ Wise (emeritus).

There is no vice so mean, so pitiful, so contemptible; and he who permits himself to tell a lie once, finds it much easier to do it a second and a third time, till at length it becomes habitual; he tells lies without attending to it, and truths without the world’s believing him…..some additional notion that he and sally hemmings didn’t have children?

And TJ took seriously such messages. Thank you!