Recently a commencement speaker exhorted graduating students to “be on the right side of history.” The commencement speaker used the phrase ‘be on the right side of history’ to mean actively supporting social trends that are currently in fashion.

But ‘the right side of history’ also implies that there are right and wrong sides of history. Indeed there are different versions of history depending on the historian doing the research and the reporting. However, for the last half-century, academia, media, and the entertainment field have offered students and the public a one-sided, highly politicized version of American history that depicts the South and its traditions as irretrievably flawed. Even public libraries in Southern cities seldom shelve books that depict the South sympathetically. Consequently many Southerners have had to assemble their own book collections.

As an addition to a Southerner’s book collection, I recommend War For What ? by Francis W. Springer. Born in 1899, Mr. Springer spent his youth in Washington, D.C. and New York City, attending that city’s schools and Columbia University. After retiring from a career in the Northeast, Springer and his wife, Beulah Hollidge, a Boston native, spent their remaining years on a farm in Charlottesville, Virginia. The couple’s fascination with American history led them to spend years of copious research into our country’s past. The result was numerous historical articles and Springer’s book War For What ?.

This little book, less than 200 pages of narrative, not only contains a wealth of information, but also presents a pro-Southern view of the ante-bellum South, including the facts surrounding the War Between the States. Springer’s technique surpasses stereotypical versions of history written for mass consumption. War For What ? contains data, cites incidents, and presents premises usually omitted from establishment-sanitized versions of history. The book presents Springer’s interpretations of the political, economical, and psychological consequences, which are interesting to consider, whether the reader agrees or not.

Francis Springer sets the stage for alternative versions of history by making reference to the Mayflower’s landing at Plymouth Rock, Massachusetts in 1620, usually considered the first English settlement in America. But Springer reminds the reader that the English colony in Jamestown, Virginia, was settled almost a dozen years earlier. And decades before Jamestown, Spain created a thriving community in St. Augustine.

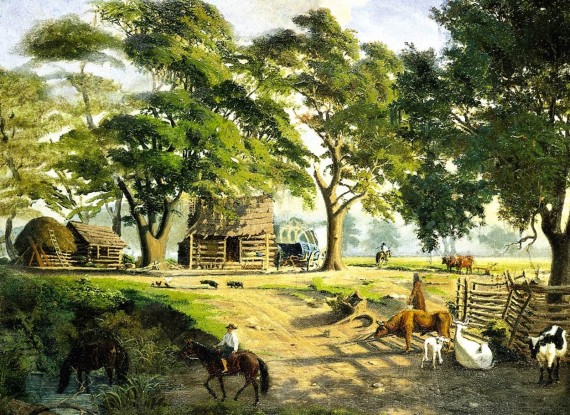

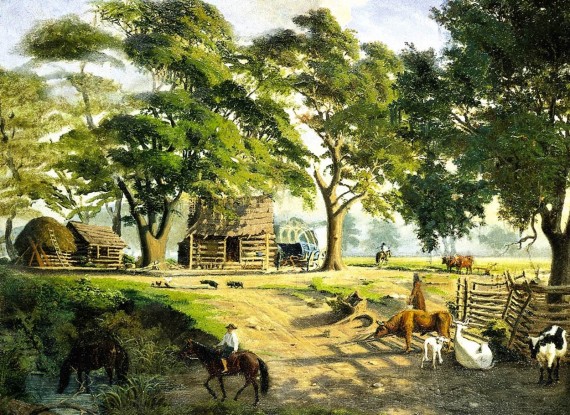

These early settlements struggled for survival, experimenting with various crops that could be successfully marketed. None were viable until they eventually began growing tobacco, emulating the farming techniques of the native Indians. With no available labor market, and because Indians refused to work for White men, various types of “indentured servants” had to be imported from England. These were Englishmen who agreed to become “indentured servants” for specific periods of time, either as punishment for illegal acts; to settle personal debts, or simply to learn how to become planters themselves. Many came from families of nobility.

War For What ? briefly describes the development of early settlements, and the addition of new crops, eventually cotton. At length, America began using Negro slaves which various nations had been importing from Africa. This became a lucrative trade as there were no governmental or societal structures in Africa, only tribes. Consequently, helpless tribal members could not protest, and certainly not vote, about their treatment by tribal chieftains.

These all-powerful chieftains amassed great wealth selling kidnapped Africans, even selling their own tribal members, to slave traders. Harsh tropical heat, disease, fever, and forbidding jungles and swamps, prevented crew members of slave ships from traveling into Africa to purchase slaves. So chained and shackled Africans were marched by their own people from deep within the African interior all the way to the sea. Those who became too ill or infirm to keep pace were abandoned to die. Historians estimate that roughly 10 million Africans died during these long, brutal marches to the sea.

Enormous wealth was also acquired at American slave ports located primarily in Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and Connecticut. One immensely wealthy Rhode Island slave-trading family began importing slaves into Charleston, South Carolina, auctioning them in that port city.

Currently sanctioned versions of the Civil War rarely mention the “Crittenden Resolutions”, passed by Congress in 1861, on the day following Bull Run, the first major battle of the war. But War For What ? discusses these resolutions that declared that the War was being fought to preserve the Union and not to end the institution of slavery. The Crittenden Resolutions were an attempt to dissuade additional slave states from joining the Confederacy: four slave states did remain with Union, refusing to join the eleven slave states that seceded.

There was also concern that Northerners would be unwilling to risk lives and limbs on battlefields simply to prevent Southern planters from using slave labor. Although many in the North might be opposed to slavery in theory, it was unlikely that they would be willing to sacrifice their lives in a war to end it.

War For What ? discusses the North’s misunderstanding of the relationship between Southern slaves and their masters. The North generally thought that all Southern slaves intensely resented their owners and were always on the verge of a rebellion or a riot. But relationships with slaves and masters varied. Also most slaves were too pragmatic to accept the simplistic abolitionist view that simply being set free resolved all their problems. These slaves had realistic concerns about what would happen after they were freed.

The puzzled mindset of Northerners couldn’t comprehend why slaves didn’t rise up against the helpless women and children left behind when Southern men went off to war. Although greatly outnumbered by slaves, women and children remained perfectly safe, even cared for, by the slaves.

When the Emancipation Proclamation was issued, many in the North assumed that freed slaves would engage in massive and violent rebellions, even massacring the families of their owners. That didn’t happen. Instead, after the initial jubilation over the Proclamation subsided, slaves came to the realization that “freedom” didn’t include a way to survive, to earn a living.

To the bewilderment of Union troops occupying the South, most slaves remained faithful to their former owners, going to considerable lengths to conceal valuables from the marauding Northern soldiers. After Reconstruction came to an end, the so-called “liberators” simply returned the North, abandoning the rootless freed slaves, who survived by negotiating cooperative farming arrangements with their former masters. Springer devotes a full chapter to authentic and moving vignettes illustrating the loyalty of Southern slaves to their master’s families.

Especially intriguing are Francis Springer’s unique interpretations of historical events which he poses for the reader to think about. Regarding the Lincoln assassination, he asks the reader to consider who stood to benefit from this atrocity. In addition to Lincoln, Vice President Johnson and Secretary of State Seward were also targeted for execution. The man who was supposed to eliminate the Vice President apparently began losing his nerve, drank himself into a drunken stupor, and couldn’t carry out his assignment. The Seward assassin fled in panic after bungling his attempt, merely wounding the Secretary of State.

Had both the President and the Vice President been killed, Congress would have chosen their successors. At the time, two of the most powerful members of Congress were Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania, and Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, two men renowned for their animosity towards the South. Mr. Springer implies that Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton of Ohio, would probably have become President because of his closeness with Stevens and Sumner. Springer wonders if any of these three men were involved in the murder plot?

Mr. Springer wonders why William Lloyd Garrison and others in the North denounced slave labor in the South while turning a blind eye to the cruel abuse of child labor in Northern textile mills. He also questions why the atrociousness of the slave trade’s “Middle Passage” with all its horrendous deaths (estimated at two million) has received less criticism than the use of slaves by Southern planters. And, as the vast majority of slaves imported from Africa ended up in Brazil, Cuba, and the West Indies, Springer asks: “Why is all the hatred directed at the South?”