I was a faithful, Southern fisherman even in New England exile. “Oh, these small mouth bass are fine,” I’d tell them, “but when I was a kid back home in Tennessee,” blah, blah, blah. “Heck, we’d have won that War if our boys weren’t off fishing all the time.” I told tales of smiling Southern bass jumping into the boat and when that was full, politely—without jostling—arranging themselves on the stringer.

I told no falsehoods. But thirty years between event and narration often changed history into docudrama; anorexic bream to bass, and adolescent pickerels into lunker pikes with pearly white daggers that would scare the bills off an orthodontist.

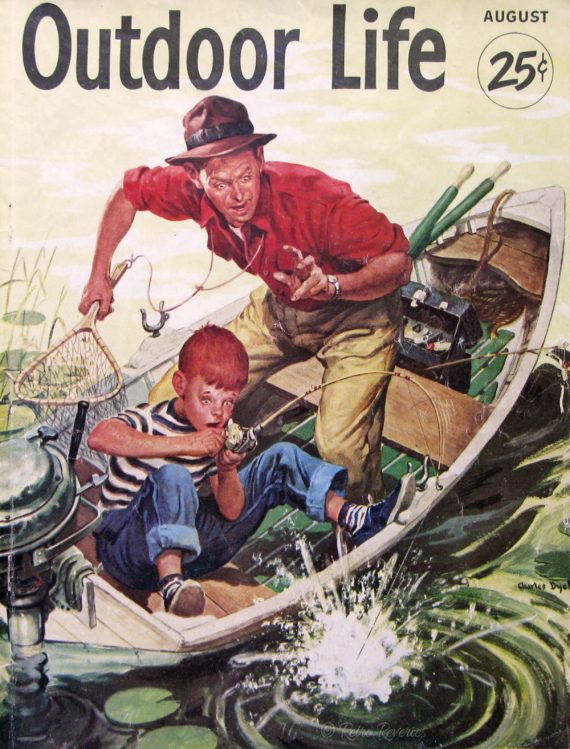

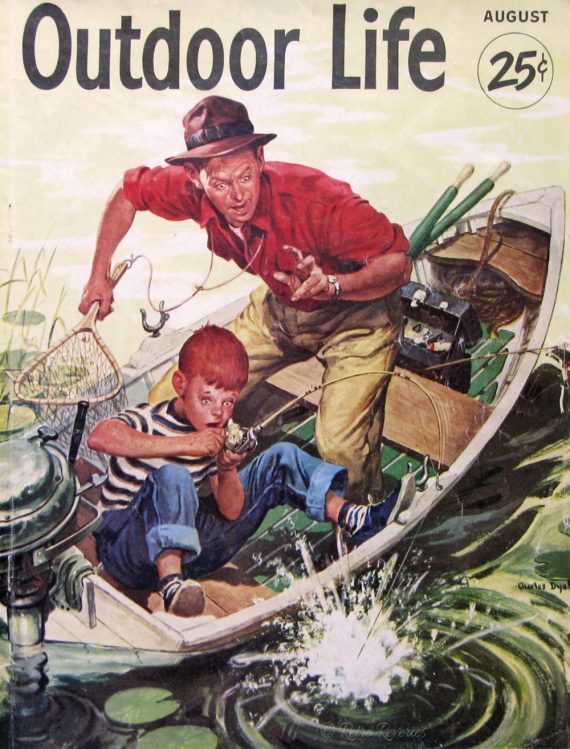

In those halcyon days my accomplice in the genocide of the Sunfish family was my pop, a better talker than a fisherman. He was Hans Christian Anderson with a fishing pole. So, who cared if the finny population of the lake fled when they heard our heavy footsteps on the pier. If the fish were sleepy or shy, there was always a classical tale to capture my fancy. Not ’til I reached the meditative age of 16 did I realize that a rowboat on a calm lake was only a prop for the of storyteller. Me and my old man; along with King Arthur, Lancelot, Sherlock Holmes, MacBeth and Hamlet crowded into an 8-foot rowboat.

That’s the way it was back then, more drama than fish. But in my exile I bragged a lot about the fertile, Southern streams of my boyhood. Never mind that the New Hampshire bass were as acrobatic as the gulls that whirled and dived over the lake.

Never mind that not a single bass swallowed his crayfish dinner without an air show and a final flyby as he roared over our rowboat. Obviously, the bream and pickerel were watching these rituals because they didn’t obediently swim up to the boat either. And even the Old and Ancient Order of Catfish made a break for it, before they surrendered to the net.

Me and my boys were in New Hampshire dunking our live baits in a 40-acre puddle called Sun Lake that neighbored the mighty Winnipesaukee. The big boys trolled 30-40 feet deep in Winnipesaukee for lake trout that were born before the ice age melted away, leaving Northeastern America full of deep, cold, blue lakes full of trout. But me and my gang caught bream, yellow perch, catfish, small mouth and pickerel on live baits in the shallows— next door in Sun Lake.

The better the New England fishing the longer my tales about the Southern lunkers of my youth. No I didn’t exaggerate. It was more like the dreamy remembrance of your sleek, streamlined ’48 Olds—your first car. Now, at the antique car show through older eyeballs, your automotive dream turned into a humpback hybrid of fact and fancy. Shorter, squattier, higher.

“Wait’ll we get back South,” was my motto throughout our New England stay. I mean, how could the fish population get fat and sassy in a Northeastern lake that only shed its ice from May to mid September. Common sense says a growing season that short had to stunt the growth of our prey. And that’s why New Englanders can’t grow watermelons, either, I told the boys. “Takes four or five nice warm months to plump up watermelons and blue gills.”

Over and over, I made my “I wish I was in Dixie” speech and lamented the sad, stunted state of the Northeastern fish population: so often and with such passion that even I was convinced that Northeastern lakes full of bream and bass and pickerel, that took a number to flop in our boat, were no big deal. Too easy to be much fun. In fact, it was almost an obligation. Who could relax over a bologna, mayo, and white bread sandwich when the bass were in such a acrobatic mood? And it certainly wasn’t as exciting as my youthful, Southern expeditions when the old man could go through the entire Arthurian cycle plus a couple of Sherlock Holmes adventures without the smallest nibble from fastidious Sunfish.

Then one bright June morning in 1976 after twenty years of New Hampshire fishing, my boss called. Who can forget that transcendental moment. It was 8:15—a Tuesday. A small green and blue fly was perched on the rim of my coffee cup; debating, I’m sure, a relaxing bath or an invigorating swim. The boss told me he was sending me back to my Southern womb. Well, not exactly— Alabama not Tennessee—but close enough.

So my tour of duty in New-England ended and we headed South. I celebrated with three barbecues for breakfast in Hunstville, Alabama the morning of my arrival. My second impulsive splurge after fifteen years of steady deliberation of my bank balance was the purchase of a modest fishing cabin on Pickwick Lake—midway between our Huntsville home and Memphis, where my grown up kids now lived.

Ah, just like the old times. A warp of time. Back to those Southern waters that bathed my youthful roots. Noble Lancelot, King Arthur, Sherlock Holmes and Watson, MacBeth and his murderous wife, and hesitant Hamlet, who couldn’t decide on scrambled or easy-over eggs for breakfast. They hung over Pickwick Lake like the morning mist.

Me and the kid met fairly often. I had retired by now; swapping a boss who rewarded me with a periodic stipend, paid vacation and coffee breaks for a wife with a checklist of daily assignments and a checkbook that was mine. But my new employer was a softy for father-son activities. Twenty years ago that other boss with the paycheck pretty much occupied my time. Family fishing trips were a luxury. Now, though the son’s wrapped in the same chains, he’s always got time for the old man.

There’s something about the lake and the hills that underlines our relationship. A great environment for a father-son seminar on life’s imponderables. I pass on the philosophical baton, so to speak. Hand him my take on life’s great mysteries; why there’s no graffiti in the ladies restroom, why only the driver’s side windshield wiper stops, why the phone company charges more not to list your number, why Southerners— amongst all the life forms existing in this kooky cosmos—put American cheese on their salad; Stuff like that. Then we talk about his spending habits (Eating out five nights a week when chicken leg quarters are 29-cents a pound), tie selection (Paisley’s only okay for underwear), child rearing (They’re my grandchildren, you know!), and football allegiances (I paid for his Alabama education based on my Business degree at UT—shouldn’t he holler Go Vols! once in a while?).

I usually wrap up my presentation with a lecture on the hereafter and its bountiful rewards for sons who obey that superseding commandment—”Honor they father and sometimes thy mother.” He listens with an expression I know so well; wide-eyed—non blinking—focused. Maybe his mind is working on a management problem at work, but clearly his face is mine.

He had always been a good listener—a prerequisite for a son with a storytelling father. And where’d all those tales of adventure, mystery, and romance come course, who thought a fishing nip was an opportunity to tell his son about King Arthur and his magnificent knights of the round table. “Good listeners make good sons.” was my papa’s watchword. Many a daring catfish escaped with his life and a fat worm because the fisherman’s body had been snatched and occupied by the storyteller.

Me and this child were bound by the father/son protocol. There’s really no precise word to describe the connection. We’re not friends—that implies equality. We certainly aren’t pals, buddies, or comrades—words that miss the generational sweep of our intimacy. It’s a time haunted kin-ship. I saw his birth—he’ll see my death. He’ll name his kids after my father and tell them his stories. In fact, he’s already started. And sometimes in front of me. I always find a discrepancy or two. “No, no Sherlock and Watson didn’t stay at the manor house that night. They were out on the moor.” Naturally, he never argues. How could he? I’m the source. Lord help me the day he has time to consult Arthur Conan Doyle.

We do okay at Pickwick. Bream and catfish and occasionally a bass who’s lost his way. Of course, we’re handicapped by the fact that I prefer the dock to the boat. Easier for a senior yarn spinner to get his mouth and mind working out of a lawn chair on the dock than a plank seat in a rowboat. We talk. The kid, who’s no longer a kid, indulges in gross exaggerations of our Northeast adventures. Time is a magician—who knows better than me.

In addition to my exposition of life’s conundrums I still sneak in a potboiler or two. He’s gotta educate his kids, doesn’t he, and where would he find time to read “The Hound of the Baskervilles”? If the fishing is slow, so much better for the storyteller and listener. Good listeners make good sons, you know.