This piece was originally published on November 16, 2012 on LewRockwell.com and is reprinted here by permission.

On 20 March 1861, United States Senator James A. Bayard of Delaware began a three day speech on the prospects of war and the legality of secession. He began by offering a resolution in the hope of avoiding what he predicted would be a long, bloody conflict. It read:

Resolved by the Senate of the United States, That the President, with the advice and consent of the Senate, has full power and authority to accept the declaration of the seceding States that they constitute hereafter an alien people, and to negotiate and conclude a treaty with “the Confederate States of America” acknowledging their independence as a separate nation; and that humanity and the principle avowed in the Declaration of Independence that the only just hosts of government is “the consent of the governed,” alike require that the otherwise inevitable alternative of civil war, with all its evils and devastation, should be thus avoided.

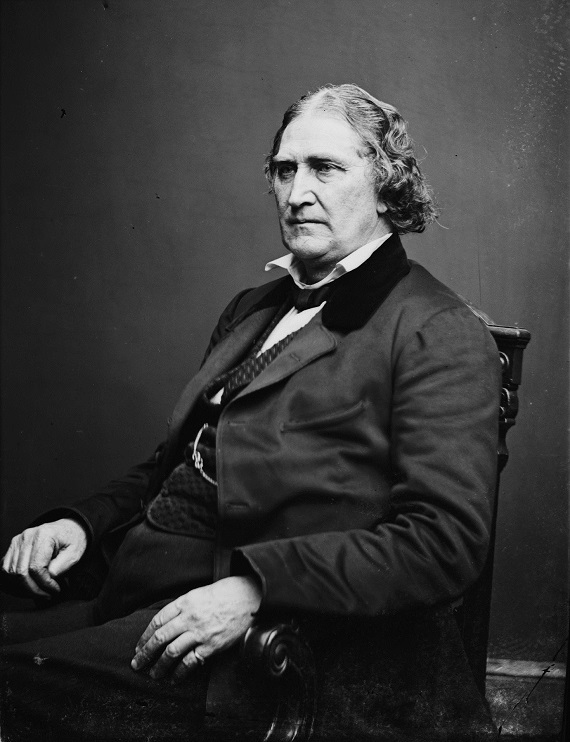

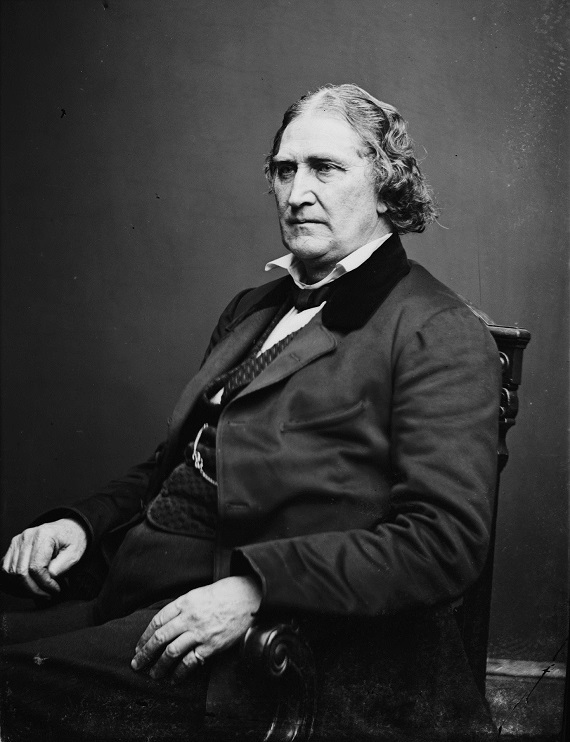

Today, November 15, is Bayard’s birthday. His is one of the most important but forgotten United States Senators in American history. There are no monuments to his honor, no buildings named after him, and outside of Delaware hardly anyone has heard his name, but he was one of the few men in the Congress with the resolve to resist the headlong rush to war the Lincoln administration and the Republican Party foisted on the American people, North and South. He privately called Lincoln an “ordinary Western man” that had no concept about American government. Bayard was a rock, a crusader waging what seemed to be, at times, a one-man defense of the Constitution and the Union of the Founders. He was threatened by mob violence, his mail was searched and was later confiscated, he was denounced in the press as a traitor, was hung in effigy in Philadelphia, and later resigned from the Senate rather than continue among the “reptiles” in Congress as he called them. Such a man deserves our attention.

Bayard openly questioned the motivation behind the war against the South and wondered aloud how people could defend such a cause. “Could there be a more revolting proposition than that the individual man, who is domiciled in the State, and residing there, shall be held in the position that he is guilty of treason against the State if he does not side with her, and of treason against the General Government if he does?” He contended “humanity alone” must side with the “law of domicile” in such a situation. When his son-in-law joined the Union army in 1861, Bayard warned, “In embarking on this war therefore, you enlist in a war for invasion of another people. If successful it will devastate if not exterminate the Southern people and this is miscalled Union. If unsuccessful then peaceful separation must be the result after myriads of lives have been sacrificed, thousands of homes made desolate, and property depreciated to an incalculable extent. Why in the name of humanity can we not let those States go?”

In a July 1861 speech entitled “Executive Usurpation,” Bayard roasted the Lincoln administration and lamented the loss of liberty. The Constitution “which we had supposed gave us, as citizens of a free country, free institutions, in contradiction to the absolutism which reigned in France” was being subverted by an administration that smacked of Louis XIV, Oliver Cromwell, or Napoleon Bonaparte. Personal liberty was the cost of centralization. “If [you cherish] the principle of civil liberty, [you] cannot sustain this action of the President [suspension of habeas corpus] which violates the laws of the land, and abolishes all security for personal liberty to every citizen throughout…the loyal States….power always tends to corruption, and especially when concentrated in a single person.”

Bayard typically reserved his harshest statements for the Republican leaders in Congress. He wrote in late 1861 that, “Their intent is the devastation and obliteration of the Southern people as the means of retaining power, and yet I doubt in the history of the world has ever, with the exception of the French reign of terror, shown so imbecile, so corrupt, so vindictive rulers over any people as those with which this country is now cursed.” He voted against appropriating money for the war effort, was dismayed by the reckless government spending – “God help the tax-payers if the money can be borrowed” – urged his son to buy gold when the National Bank Acts passed, thundered against their attempts to expel members of Congress for their opposition to the War, denounced troops at the polls, the military occupation of Delaware, and the arrest of dozens of Delawareans for suspected disloyalty, and believed that the “more moderate” Republicans were being “governed by the violent and ignorant.” He wrote, “If the people of the U.S. were not more practical and informed than the element the French Jacobins dealt with I believe we should have the atrocities of the ‘Mountain’ renewed. Fear alone sustains them.” In 1862 he wrote, “State necessity has always been pleaded for the suppression of liberty.”

Recent events, of course, make Bayard relevant. Tomorrow, thousands of Americans will flock to see Stephen Spielberg’s new film about “Honest Abe,” and will doubtless leave feeling a surge in admiration for the “Great Emancipator.” Assuredly, Bayard’s description of events will not make the film. At the same time all fifty States and over 675,000 people and counting have petitioned the White House to accept the peaceful separation of their State from the Union. Barack Obama has compared his administration to Lincoln’s. Perhaps the two have more in common than he realizes.

Lincoln, the dishonest, Hamiltonian, dictator, and Obama, the Marxist, Keynesian, emperor, both have shredded the Constitution and both have faced a decision on how to handle open defiance of their administration. Obama’s will mirror Lincoln’s, at least in regard to the legality of secession. Secession, he will say, is illegal, unconstitutional, treasonous, and unpatriotic. And why not, he has so-called conservative support. Bayard said in 1861 that “I believe the great value of the American Union…is the preservation of liberty – by which I mean a Government of laws, securing the right of free speech, securing the freedom of thought, and securing the free and ample discussion of any question.” The American people may not be ready for secession and are going about it the wrong way, but let’s hope there is a James Bayard in the current crop of United States Senators, someone with the manly resolve to contest the flimsy arguments that will certainly be used against the American principles of independence and self-determination. I don’t have much optimism.