This selection was originally printed in Brion McClanahan and Clyde Wilson, Forgotten Conservatives in American History (Pelican, 2012).

Of the Great Triumvirate who dominated American public discourse from the War of 1812 till the mid-19th century, John C. Calhoun was the first to depart the scene, in 1850. Henry Clay and Daniel Webster lived a few more years. In a generous eulogy for the man who had been his opponent for forty years, Webster, realizing that an epoch of American history was drawing to a close, called Calhoun “a Senator of Rome when Rome survived.” Calhoun’s aspirations were always “high, honorable, and noble,” Webster said, and “nothing low or selfish” ever “came near the heart or the head of Mr. Calhoun.”

To appreciate Webster’s words it is necessary to appreciate the importance which the example of the Roman Republic had for the first generations of independent Americans. The republican heroes of ancient Rome, as known through Livy and other historians, were models of principled republican patriotism in a world that had long been dominated by feudalism and monarchy. A statue of George Washington in a toga was considered very appropriate. Indeed, Washington’s favorite literary work was Joseph Addison’s play about the Roman hero “Cato.” The upper chamber of American legislators were known as Senators, and they met in a capitol building. The model hero for American republicans was Cincinnatus, who left his plow to lead an army in successful defense of his country and then took up the plow again without any thought of using his prestige for personal ambition that might undermine the public liberty. (It doesn’t matter that some historians assert that our forefathers did not really understand Rome. The significant point is what their beliefs say about them.)

The notion that Calhoun was all about slavery and nothing but slavery is a product of the current reign of Cultural Marxism and does not represent a balanced view of American history. It has not always been so. In 1950 Margaret Coit’s admiring biography, John C. Calhoun: American Portrait, won a Pulitzer Prize. In 1959 a committee chaired by John F. Kennedy named Calhoun as one of the five greatest Senators of all time. Calhoun’s A Disquisition on Government has been recognized in every generation and internationally as among the most important political treatises written by an American.

It is somewhat ridiculous to single out Calhoun as a defender of slavery when no one in his time proposed any serious solution to the slavery question. Indeed, Lincoln himself on his election declared he would not know what to do about slavery even if he had the power, which he did not have. Calhoun was forthright in condemning agitation in the North about slavery in the South, warning that it was threatening the bonds of Union. In the last few years of his life, in response to the Wilmot Proviso, which barred the South from use of the new territories acquired from Mexico in violation of the Missouri Compromise, Calhoun did become the most conspicuous proponent of a defensive Southern unity within the Union. By that time Calhoun already occupied the position of elder statesman who was admired and listened to by thoughtful people North and South for his adherence to principle and independence of political party maneuvers.

He had been an eloquent and tireless leader of the House of Representatives during the War of 1812 and one of the main architects of postwar legislation in which he had shown a constructive spirit generous to the welfare of every part of the Union. As Secretary of War, a thankless post, Calhoun had been one of the ablest department heads ever serving in the U.S. government. He had been elected Vice President virtually without opposition and had resigned from that position on a matter of principle. His years of service in the Senate (1833—1843, 1845—1850) were interrupted by a year as Secretary of State. It is a measure of his stature that when President Tyler nominated him to be Secretary of State, at a time of impending conflict with both Britain and Mexico, Calhoun was confirmed by the Senate in a matter of hours without a single dissenting vote, even from the antislavery Senators of Vermont.

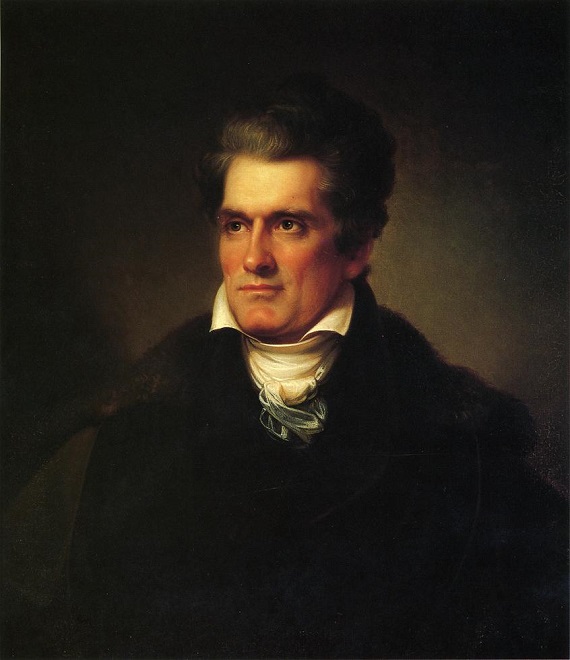

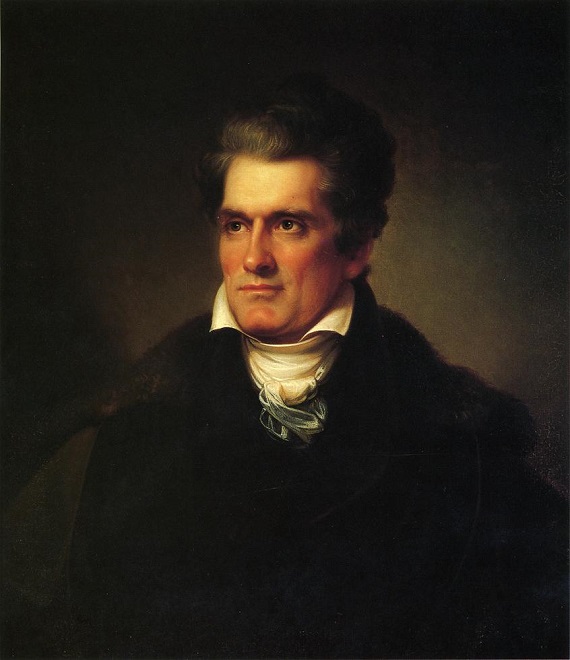

Nor was Calhoun a “cast-iron man”—except in principles. His image today is a good object lesson in the proclivity of some historians to resort to cartoon versions of history when dealing with figures they do not like. The description of the “cast-iron” man so often quoted was made by a cranky Englishwoman who met him once briefly. And the Brady daguerreotype usually displayed to portray Calhoun as a dour fanatic was taken during his final illness. Portraits and commentary offer abundant evidence that Calhoun was a handsome, charming, and approachable, as well as a brilliant man.

Americans have long been predominantly a pragmatic people, eager to get on with what seems desirable public policy without much attention to principles and philosophy. So that much of what the Roman Calhoun regarded as necessary for the preservation of a healthy republic will seem strange and irrelevant, or even repulsively stern in the twenty-first century. On the other hand, his observations often are those of a gifted prophet who accurately foresaw perils that the United States has failed to avoid.

A good example of Calhoun’s insistence on republican virtue: In 1842, near the end of the session, the Senate was hearing routine committee reports. A report recommending compensation to the heirs of General William Hull brought Calhoun to his feet:

Mr. Calhoun said that he was not a little surprised. . . . He was, in the first place, surprised that the representatives of General Hull should ever think of presenting this claim to Congress. He would not be more so, if the representatives of [Benedict] Arnold should present a claim for his pay as a general in our service…on the ground that he held the commission of a general, which had not been revoked. . . . He could never forget the deep and universal indignation which pervaded the whole country on the surrender of Detroit [by Hull at the beginning of the War of 1812, without firing a shot]. . . . How could his pay as Governor be allowed, when there was, for the time, no such Territory as Michigan? It had, by his own act, become a British province and remained so until it was re-conquered by the army under General Harrison. With what show, then, of justice or equity, could he be paid for governing a territory, that did not exist, and which had ceased to exist by his own act? The error of the committee consisted in supposing that the commission—he mere paper and wax—and not the service, gave the pay.

A similar recurrence to antique republican honor was evoked when the Smithson bequest came before the Senate. James Smithson, a wealthy Englishman, had willed to the United States an endowment for a university. Calhoun observed that Congress in fulfilling the bequest would be allowing a foreigner to empower it to do what had previously been determined to be unconstitutional. “I not only regard the measure as unconstitutional,” he said, “but to me it appears to involve a species of meanness which I cannot describe, a want of dignity wholly unworthy of this Government.” He continued, “We would accept a donation from a foreigner to do with it what we have no right to do, and just as if we were not rich enough ourselves to do what is proposed, or too mean to do it if it were in our power.”

Calhoun believed that government expenditures should be minimal and closely monitored. It was unusual in his time and is perhaps shocking to Americans who have long since thought of politics mostly as a jockeying for government benefits. “We robbed the people in levying taxes. It was plunder and nothing more. . . . Every cent removed from the hands of Government is so much added to the wealth of the people. . . . Every dollar we can prevent from coming into the treasury, or every dollar thrown back into the hands of the people, will tend to strengthen the cause of liberty, and unnerve the arm of power.” This sentiment did not mean that he approved the plans of politicians to “distribute” to the governments of the States a treasury surplus brought about by an unjust tariff. This was not giving it back to the people from whom it had been unnecessarily taken, but merely expanding the opportunity for politicians to buy support. In what must be one of the most extraordinary acts of principle in American history, South Carolina refused its share of the unjust distribution.

On other occasions Calhoun called the attention of the Senate to unwelcome truths: “We all knew that when a public building was commenced that it was never finished under five times the original estimate.” It was almost impossible to repeal a tax once it had been placed on the books, he said. And whatever the claims of political parties: “All Administrations were nearly alike extravagant . . . It was impossible to force the minds of the public officers to the importance of attendance to the public money because we have too much of it.” “I have no doubt, from what I daily see,” said the stern republican, “that our whole system is rapidly becoming a mere money making concern to those, who have the control of it; and that every feeling of patriotism is rapidly sinking into an universal spirit of avarice.”

A modern authority on banking and currency has written that John C. Calhoun understood that complex and contentious subject better than any public man of his time. Characteristically, he refused to be drawn into the party argument between the Whigs and Democrats over whether there should be a national bank or not. He made a deep historical study and his speeches of the 1830s and 1840s on this subject are models of learning and independent statesmanship. Both parties were failing to deal with the fundamental question—who should control the money supply (currency and credit) of the country? The Democrats’ Independent Treasury, to do the government’s banking business instead of a national bank or Jackson’s corrupt system of “pet banks,” was a step in the right direction. However, it did not go far enough. The Independent Treasury would continue the long established government policy of treating the notes of private banks as acceptable money Therefore, the banking system would retain a large amount of control over the money supply (its expansion or contraction} which meant great power over the whole economy and every other interest. “We must curb the banking system,” said Calhoun, “or it will certainly ruin the country.”

I do not hesitate to say, if Genl. [Alexander] Hamilton had not issued his circular directing bank- notes to be received as gold & silver in the public dues, and if the Bank of the United States had not been created, the whole course of politics under our system would have been entirely different.

Further, why should the U. S. government, which had a large income, create a national debt by borrowing money from bankers, who thus were paid interest at no risk to themselves? Rather, there should be a complete “divorce” of the government and the bankers. Congress had the responsibility to provide a sound circulating currency for the business of the country. The government should issue its own money, Treasury notes, which, based on its credit, would fulfill this obligation and eliminate the connection with bankers.

When the Independent Treasury came to a vote, Calhoun offered an amendment to phase out the Treasury’s receipt of bank-notes. The majority Northern Democrats were not about to offend the bankers and his proposal was voted down. Very seldom has a more fundamental challenge been offered to “business as usual.” Calhoun had cut through party polemics to the fundamental truth: the alliance of government and bankers gave control of the money supply to private interests to the detriment of every other interest in society. “’It has been justly stated by a British writer,” Calhoun told the Senate, “ that the power to make a small piece of paper, not worth one cent, by the inscribing of a few names, to be worth a thousand dollars, was a power too high to be entrusted to the hands of mortal men.”

As always, Calhoun’s ultimate concern was not with money but with the health of republican liberty. He deplored the effects of the banking system on the public morale. The unnatural rewards of banking were diverting able young men from the honorable and useful learned professions and their attention from patriotic service.

Calhoun’s warnings of the degeneration of statesmanship due to the development of party organizations and professional politicians was a great source of appeal to thoughtful people in every part of the Union. The Hamiltonians and Jeffersonians had been patriots who had fought over differing visions of America. But the Whigs and the Democrats were primarily election machines. Their campaigns avoided real issues and sought to occupy the non-controversial middle, to be all things to all men. When the issue was protective tariff or no protective tariff, Andrew Jackson had come out for a “judicious tariff.” In 1840 the Whigs elected a president with a noisy and meaningless campaign. In 1844 when the important issue was the status of Texas, the Whig frontrunner Clay and the Democratic frontrunner Van Buren colluded to not mention the issue at all in the presidential campaign, because a clear stand could make trouble for both. Calhoun as Secretary of State disdained this evasion and forced the issue of Texas into prominence. Van Buren thus lost the nomination to a pro-Texas candidate, James K. Polk

As Calhoun wrote a young friend:

The Federal Government is no longer under the control of the people, but of a combination of active politicians, who are banded together under the name of Democrats or Whigs, and whose exclusive object is to obtain the control of the honors and emoluments of the Government. They have the control of the almost entire press of the country, and constitute a vast majority of Congress, and of all the functionaries of the Federal Government. With them, a regard for principle, or this or that line of policy, is a mere pretext. They are perfectly indifferent to either, and their whole effort is to make up on both sides such issues as they may think for the time to be the most popular, regardless of truth or consequences.

Calhoun was a vigorous critic of the solidifying system of political party “conventions of the people” to make platforms and nominate candidates. Such proceedings did not represent the voice of the people, but were gatherings of self-interested politicians held together by patronage or the promise of patronage. And were invariably stage-managed and predetermined by clever professional politicians. “This wholesale traffic in public office for party purposes is wholly pernicious and destructive of popular rights,” Calhoun said. The “people individually, have no choice, but to vote for the one ticket or the other ticket . . . .Never was a scheme better contrived to transfer power from the body of the community, to those who occupation is to get or hold offices . . . .”

A 21st century American, contemplating the bottomed-out “approval ratings” of public officials, might be inclined to consider Calhoun as a prophet:

When it comes to be once understood that politics is a game; that those who are engaged in it but act a part; that they make this or that profession, not from honest conviction, or intent to fulfill it, but as the means of deluding the people, and through that delusion to acquire power; when such professions are to be entirely forgotten, the people will lose all confidence in public men. All will be regarded as mere jugglers—the honest and the patriotic as well as the cunning and the profligate—and the people will become indifferent and passive to the grossest abuses of power, on the ground that those whom they may elevate, under whatever pledges, instead of reforming, will but imitate the example of those whom they have expelled.

On another occasion he remarked that in order for self-government of the people to work:

It will be by drawing into the Presidential canvass and fully discussing all the great questions of the day. One of my strong objections to the caucus system is that it stifles such discussions, and gives the ascendancy to intrigue & management over reason & principles. It is in fact an admirable contrivance to keep the people ignorant and debased.

It was frequently said by opponents and has been repeated by historians that Calhoun was too idealistic for politics. One superficial historian has even said that Calhoun “was out of touch with reality” during the Nullification crisis of 1831—1833, despite the fact that Calhoun and his “gallant little State,” standing against almost the entire political power of the Union, achieved a reduction of the tariff.

Such critics miss the point. Calhoun was not out of touch with reality, he simply disdained the “reality” of ordinary political expediency and compromise. He strove to be a statesman. A politician was one who cut deals to achieve and keep office. The duty of a statesman was to acquaint the people with the big picture, with the long-range consequences of seemingly expedient measures. A statesman would foresee avoidable dangers. Near the end of his life Calhoun solemnly and accurately predicted that unless his countrymen changed their ways, the Union would be disrupted within a decade.

Calhoun strongly supported the War of 1812, which he regarded as a necessary defense of American honor against intolerable provocation. There was much opposition to the war. Calhoun made these sensible and moderate remarks to the House of Representatives on the question of opposition in wartime:

How far the minority in a state of war may justly oppose the measures of government, is a question of the greatest delicacy. On the one side, an honest man, if he believed the war to be unjust or unwise, would not disavow his opinion; but on the contrary, an upright man would do no act, whatever he might think of the war, to put his country in the power of the enemy. It is this double aspect of the subject which indicates the course that reason approbates. Among ourselves at home we may contend; but whatever is requisite to give the reputation and the arms of the republic superiority over its enemy, it is the duty of all, the minority no less than the majority, to support. . . . In some cases it may possibly be doubtful, even to the most conscientious, how to act. It is one of the misfortunes of differing from the rest of the community on the subject of war.

In monarchies, the decision to go to war was made by the ruler. But for the United States, war “ought never to be resorted to when it is clearly justifiable and necessary.” In a republic, war must never be undertaken except when circumstances “will justify it in the eye of the nation.” And war must always be undertaken gravely and honorably, without “bullying” and threats “nor the ardor of eloquence to inflame our passions.”

It is in regard to foreign relations and war that Calhoun made his most telling and unheeded prophecies about the consequences of violating true republican principles. Calhoun delighted in the expansion of the American people across the continent. It was the very energy and enterprise of the American people that made war unnecessary. Their own unofficial efforts would bring under American control all the territory that could reasonably be desired:

Peace is, indeed, our policy. Providence has cast our lot on a portion of the globe sufficiently vast to satisfy the most grasping ambition, and abounding in resources above all others, which only require to be fully developed to make us the greatest and most prosperous people on earth. . . . let a durable and firm peace be established, and this Government be confined rigidly to the few great objects for which it was instituted; leaving the States to contend in generous rivalry, to develop, by the arts of peace, their respective resources, and a scene of prosperity and happiness would follow heretofore unequalled on the globe.

The U.S. government had no need for” provocative words and acts, much less conflicts with other powers. All the government needed was a policy of “masterly inactivity.” As Secretary of State he worked toward a compromise with Great Britain over the Oregon territory, realizing that despite the demands of some for “54 40 or fight,” it would be counterproductive to go to war with the greatest power on earth where there was no possibility to place and supply an army. After much bluster, the Polk administration was forced to accept the compromise settlement that Calhoun had made.

Calhoun’s statesmanship never showed better, perhaps, than in his stand on the Mexican War. Texas had won its own independent nationhood, and thanks to John Tyler and Calhoun had become a member of the American Union. Tensions remained high with Mexico over the boundaries of Texas and other matters. Polk on assuming office sent an army force to occupy the barren land between the Nueces and Rio Grande rivers, which Mexicans asserted was not part of Texas. A clash occurred with Mexican forces in the disputed area. When the news of this reached Washington, Polk declared that “American blood has been shed on American soil” and asked Congress to recognize a state of war.

Calhoun raised a lonely voice against the surge of patriotism that ensued. He refused to support the war resolution in the Senate. A border incident did not necessarily call for all-out war, he said. Most importantly, a perilous precedent had been set. The President had in effect initiated a war without waiting for the people or Congress. If this precedent were allowed to stand, it would empower any future President to commit the country to war at will. And so it has been.

We can measure the quality of Calhoun’s statesmanship and love of democratic government when we realize that the war was very popular, especially in the South, and when we compare him with most of the Whigs in Congress. Opposed to the war and the Polk administration, they nevertheless voted for the war resolution out of fear of being branded as unpatriotic, and then voted no on all legislation to supply the army.

As the war progressed Calhoun repeatedly argued for limited war aims and against the rising clamor of Manifest Destiny. Let the U.S. be satisfied with Texas, New Mexico, and California and not invade and occupy Mexico. His remarks might apply to the 21st century as well as the 19th:

We make a great mistake in supposing all people are capable of self-government. Acting under that impression, many are anxious to force free governments on all the people of this continent, and over the world, if they had the power. It has been lately urged in a very respectable quarter, that it is the mission of this country to spread civil and religious liberty over the globe, and especially over this continent—even by force if necessary. It is a sad delusion. None but a people advanced to a high state of intellectual and moral excellence are capable, in a civilized condition, of forming and maintaining free governments; and among those who are so far advanced, very few indeed have had the good fortune to form constitutions capable of endurance.

The attempt to create a free government in Mexico would only result in the U.S. installing and permanently propping up by force a puppet government, as the British had done in India. Sound familiar? At this time Calhoun wrote his daughter, his closest confidante:

Our people have undergone a great change. Their inclination is for conquest & empire, regardless of their institutions & liberty; or, rather, they think they hold their liberty by a divine tenure, which no imprudence, or folly on their part can defeat. . . . We act, as if good institutions & liberty belong to us of right, & that neither neglect nor folly can deprive us of their blessing.

To those of a conservative disposition, Calhoun may seem to be a prophet, the full import of whose warnings are yet to be seen.