A review of four novels by Dr. James Everett Kibler, Jr: Walking Toward Home (Pelican Publishing, 2004), Memory’s Keep (Pelican Publishing, 2006), The Education of Chauncey Doolittle (Pelican Publishing, 2008), and Tiller (Shotwell Publishing, 2016).

At the heart of every good work of fiction are characters that are believable and a real or imagined setting that allows readers to inhabit, if only for a while, the places described on the printed page. In James E. Kibler, Jr.’s Clay Bank Series of four novels, Walking Toward Home, Memory’s Keep, The Education of Chauncey Doolittle, and Tiller, he masterfully creates a landscape and a recurring cast of characters that are as warm and delightful as sitting by an open fire on a cold winter evening, and as refreshing as walking barefoot through newly plowed earth on a warm spring day

While each of the novels can be read independently as complete and separate works, the collection, set in fictional Clay Bank County, South Carolina, is bound together by themes common to the canon of venerable Southern literature: a reverence for the land, the bonds of family, and the importance of faith. The books are further entwined by a gleaming thread of decency and propriety that runs rich through the patchwork of people inhabiting Kibler’s literary landscape.

A company of well-defined supporting players surrounds the principal character Triggerfoot (Trig) Tinsley, and his close friends Chauncey Doolittle, Kildee Henderson, and Clint Blair. Those men, although different in age and temperament, are long-time friends. All four are descendants of an enclave of pioneer families who have inhabited the Upcountry region of the state for more than two and a half centuries. In their veins is the blood of men and women who stood firm against British tyranny in the 18th century, and equally strong against another invading force in the century to come.

Each one of the main characters exhibits qualities of Southern manliness embodied in their resourcefulness, raw determination, and pride. Together they persevere through trials and tribulations that include droughts and storms, disease and deaths, and the onslaught of commercial, industrial, and residential development that threatens the pattern of their daily lives. As with real life, the same characters revel in good days of births and baptisms, weddings and family reunions, quiet times filled with deep contemplation, conversations with cherished friends, and raucous occasions filled with laughter, music, and great cheer.

Unlike novelists who take readers far back into the past to a time that is only vaguely comprehendable today, Kibler’s characters exist in the more recent past, as well as the present day. Kibler’s mission is not to create an ideal world where his characters are shielded against the onslaught of modernization. Instead, he moves his characters through time without letting it change them in ways that abandons the past. Their moral compass remains as constant as the North Star, even when the world around them has turned its back on many of the time-honored traditions and practices of their ancestors.

The characters in Kibler’s novels live in houses that are generations old, surrounded by ancient cedars, walnuts, and oaks. They heat with wood, draw their water from wells, and hang out their wash to dry on clotheslines. They don’t set alarm clocks, but arise each morning before dawn. They arrive early to work and stay late on the job with a willingness to always help a neighbor in need. They raise crops and livestock, and they know how to hunt, fish, and forage for food in the forests. They pay their debts and vow never to mortgage their land to pay for tools and machines that will make their lives easier. Instinct tells them that man-made goods often wear out before the final bills have been paid.

The closely-knit community of people created by Kibler expects to be given nothing for free. They believe in hard work, and they live in the modern world without clamouring for its promise of wealth. The concept of genuine thrift is displayed in numerous ways as they make do with what has been passed down to them. In turn, they use and reuse every material object in their possession, and discard nothing until its uses are truly exhausted. Food is never wasted, and nature’s bounty is shared, not hoarded.

Kibler’s characters are unashamedly Christian and often know the Holy Scriptures as well as they know their own names. They look to their maker for guidance and forgiveness when they fail, and they pray and offer thanks for the blessings and mercy they have received. When death comes they celebrate the life of the one who has passed away comforted by the promise of eternal salvation.

The colors, aromas, and sounds of Clay Bank County are made even richer by a generous dose of legends and traditions brought to this land by Irish, Scottish, English, German, and African forebears. In that light, Kibler’s community of related souls is a microcosm of the American South. White and black citizens live in harmony, and success and respect is not limited to one race. Genuine neighborliness and kindness are the rule, not the exception.

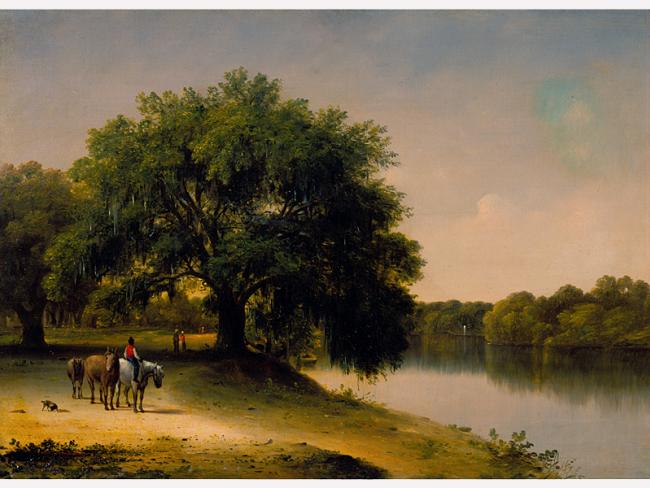

Like novelist and poet Fred Chappell, Kibler is a true regionalist. He speaks with the unmistakable authority of a native son of the South. And he writes with a passion for the place in which his characters reside. As with William Faulkner’s fictional Yoknapatawpha, Mississippi, and Harper Lee’s, Maycomb, Alabama, Kibler’s Clay Bank County is an imaginary place that is rooted in the true experiences and places of his own past. Visit the small towns and farming communities of Newberry, Union, and Fairfield counties in South Carolina, and you can almost expect to see Kibler’s characters walking the streets, plowing the fields, and fishing the rivers and streams.

Readers familiar with Kibler’s ancestral landscape of Upcountry South Carolina will easily envision the timbered hills, fertile bottomland, and wide rivers that he describes in his novels. The rhythm and cadence of Southern speech, true of Kibler’s own family and neighbors, is revealed in each book. It is one of the most important traits that ties each of his characters together, and it represents one of the greatest heirlooms they possess.

There is a reverence for nature in each of the books, and Kibler’s characters are attuned to the seasons and have an ingrained respect for the soil. They understand that creatures of the earth and sky, as well as the moon, stars, sun, and clouds can be used to predict changes in the weather. The novels are generously laced with the sounds of bobwhites and whippoorwills, the rustle of leaves, the distant yelp of hounds, and rain on tin roofs. Other sensory elements are used so effectively that the reader will think they are experiencing them for themselves.

Kibler’s readers can all find something to cherish and celebrate in getting to know the residents of Clay Bank County. The overall theme of the series is the importance of home and family. That idea is expressed best by words that Trig Tinsley once recalled hearing from his grandfather. “Young’un, happiness ain’t getting what you want, but knowing how much you already got. And it ain’t wanting to be somewhere else, but being thankful for where you are.”

My advice to the reader is this: If you can’t find what you’re looking for in Kibler’s Clay Bank County, it ain’t worth looking for in the first place. Each book is a treasure waiting to be shared.