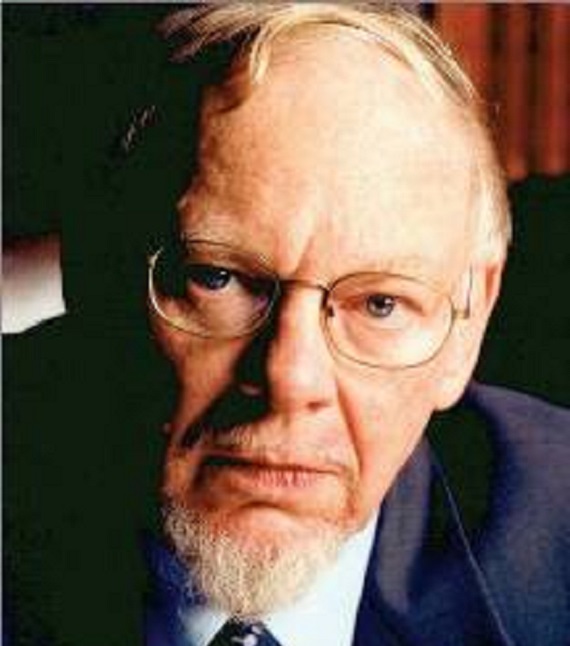

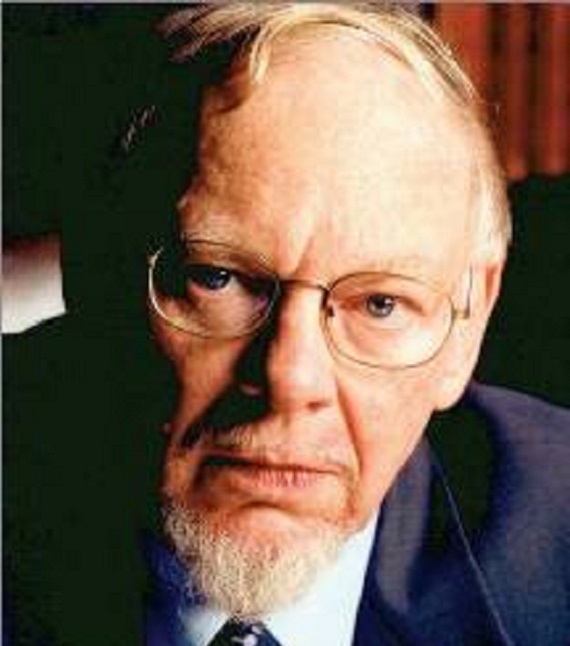

I first met Dr. Clyde Wilson in February 2018 at an Abbeville Institute conference in Charleston. I had been reading his many works since I began becoming more intellectually curious about Southern tradition, the War, Reconstruction, and the New South, my own Confederate ancestry, and what it all means for the world today. Once you crack the veneer of the Lincolnian mindset, you simply can’t avoid Wilson’s voluminous writings.

So, being the shameless dork I am, I introduced myself at the Friday night meet-and-greet and asked if he’d let my husband snap a picture of the two of us. So the man who’s considered the greatest living Southern historian humbly obliged, even though I’ve now learned he’s not a fan of posing for photos. What a gentleman.

Since then, Wilson has become a mentor to me. He encourages young and late-to-the-game Southern writers. He’s quick with a compliment if he thinks it’s deserved, but won’t pull punches if need be.

The last time I saw Wilson, he was wearing a “Grumpy Old Man” baseball cap, which I think so typifies him. Not because he’s crotchety, but because he doesn’t suffer fools. He motivates and educates, and advocates for anyone who he thinks is fighting the good fight. He’s just glad you’re trying to play catch-up with a master.

Simply put, Clyde Wilson is a gracious Carolina lion. I hope you all enjoy this 4-part series, which has been a long time in the making, as much as I am honored to have conducted it.

“The wicked flee when no man pursueth: but the righteous are bold as a lion.” — Proverbs 28:1

DM: How would you define the Southern tradition? In other words what makes it true and valuable?

CW: Thanks for this opportunity. It is gratifying that an outstanding young person like you thinks that I have something to say. And this gives me an occasion to do some long-term and big-picture thinking that isn’t easy in the daily strife.

May I change the question slightly and ask how I define Southern? If there is a tradition then presumably there is, or at least used to be, a reality called the South. We tend to talk of Southern “tradition” as a genteel means these days of getting a hearing for the proposition that there might indeed be something true and valuable from the South. If you simply talked about what is Southern as true and valuable, you would get an automatic negative reaction. But tradition suggests something that is past and not so threatening.

There is indeed much that is true and valuable in the life and history of the Southern people that is available to all the world if they will listen. I am tempted to say that what is most true and valuable about the Southern tradition is that it is ours. The South is well over three centuries old, much older than what is now called the United States. In the beginning, America was Southern. Now we are a despised minority in our own country. There are still millions of us. We could be a great power if we were united in our consciousness as Southerners.

“I am tempted to say that what is most true and valuable about the Southern tradition is that it is ours.”

The great M.E. Bradford 40 years ago defined the South as “the expression of a vital and long-lasting bond, a corporate identity assumed by those who have contributed to it.” He was aware when he wrote that most Southerners no longer live on the land, but was suggesting that the bond, an ancient way of being, still had life. And that such a way of being was better for those who shared it than the abstract supposed principles that define the United States.

At the same time that Bradford wrote, with a youthful presumptuousness that still scares me, I attempted a definition: “the South has always been primarily a matter of values, a peculiar repository of intangible qualities in a society peculiarly preoccupied with the quantifiable.”

Like all human people, Southerners arise from a particular history and geography. But being Southern is essentially a matter of soul. I know I am Southern. You know you are Southern. We know it in other people when we see it. Being Southern is a good thing and the more intelligent young people know this. It becomes weaker, perhaps, every day, but it is still here. And we know that being Southern means we share assumptions and attitudes that many other Americans do not know and do not understand and often intensely object to.

According to Richard Weaver, Southerners still have a connection to the spiritual realm that makes up Western civilisation, when the rest of the West has abandoned that civilisation for materialism and rationalism. If so, that is a product of our history and not something we can brag about and take credit for.

“Being Southern means we share assumptions and attitudes that many other Americans do not know and do not understand and often intensely object to.”

I have written a lot about the Yankee Problem. By Yankee, I do not mean all Americans who are not Southern. I mean that breed arising from the Deep North that has usually had the most influence and power in America since 1865. I know half a dozen Italian-Americans who are simpatico with the South – like Southerners, they have souls. They are products of a genuine culture.

Good examples of Yankees are George W. Bush and Hillary Clinton. Yankees have no souls. They are creatures of material (money) and abstractions. Consider the insistence that America is “a proposition nation” and anyone who agrees with the proposition is an American. Can you think of anything more obviously absurd? Our country is not its people, its land, its way of life, its religion, its history. It is a slogan. The slogan is “All men are created equal.”

Now that is a very good idea that should govern the behaviour of Christians toward other human persons. But there cannot be any such country. What is happening here that is the slogan gives power to those who see themselves as entitled to interpret it.

Consider this. Yankee Minniesotans think they have the divine right to sit in judgment on Mississippians and force them to do what the Minniesotans want them to do. Now it would never occur to Mississippians to dictate to Minnesota. It is not in their DNA, or rather it is not in the remnants of their Western culture. They can go months or even years without even thinking of Minnesota.

America “is not its people, its land, its way of life, its religion, its history. It is a slogan.”

And the Yankee always acts with self-righteousness, ill-informed shallow knowledge, and the most stupendous hypocrisy known in history. Part of being Southern is knowing that these people actually hate you for what you are. They have hated you ever since the first settlers came ashore in Massachusetts Bay. Southerners are loyal to and do their best for the United States, which we think of as our country. However, we are linked in a Union with people who hate us. The hatred is not in what we are, but in what they are.

DM: We hear a lot about “the Southern cause.” How do you define that?

CW: We hear a lot, as you say. In my opinion, the only real Southern cause is preserving and perpetuating the Southern people in a maliciously hostile environment. That will require an increasing sense of unity as “Southerners.” It is not primarily a political thing, yet unavoidably, self-government and freedom require political power.

Consider, the South does not have a single representative in the U.S. Congress today. We have people who represent the Republican party or the Democratic party. In the 1960s when Southerners were kicked out of the Democratic party (which we created and which had always been ours), if only our leaders had formed a Southern party, rather than opportunistically joining the Republicans who had always been unrepentant enemies of the South and still are!

“Self-government and freedom require political power.”

DM: How did you meet Dr. Livingston, what prompted y’all to start the Abbeville Institute, and did you ever think Abbeville would be as influential as it is?

CW: Let me make it clear that the Abbeville Institute was entirely Professor Livingston’s concept and initiative. I got involved to give what help I could. We got acquainted, as I remember, because we were both writing seditious articles for the same publication, and so made contact. The influence of the Institute has truly been amazing. The scholarly quality is not matched any where else today. I have more than once heard graduate students say that they had more intellectual meat at the Abbeville Summer School than in a year of regular study. Don Livingston has a very great legacy.

DM: How did you become interested in Southern history? Was it part of your rearing? Or was there something else that happened or you learned that spurred you toward this passion? On one hand, I would think it might be generational, but on the other, there are so many Southerners of your generation who couldn’t care two hoots about Southern heritage. Why do you?

CW: I might mention that my grandmother, who I spent a lot of time with during World War Two when I was a toddler, was the daughter of the last Confederate veteran in North Carolina. All my Confederates on both sides were privates, except for one corporal. More importantly, my grandmother knew a lot about the history of North Carolina and other things. We followed the war news every day, then by radio and newspapers, with real interest because my father and all the numerous uncles on both sides were in peril. One did not come back alive. History was relevant to my life from an early day.

“I was not a child of the Sixties, like most folks today, but an automatic critic of its absurdities.”

I was a prewar baby, as Grandmother used to emphasise. War babies might have appeared by an element of accident. I was thus of that unnamed generation who was an adult when the Sixties hit. I was not a child of the Sixties, like most folks today, but an automatic critic of its absurdities. I had not learned that it was a noble, progressive thing to join the enemies of your own people and acknowledge their superiority.

I had experienced the “Civil War Centennial” and learned a lot about the attractive side of Southern heritage. I had studied enough history to know that there are at least two sides to a question when the upheavals of the ’60s and ’70s hit. Television was just in the childhood of its power, and I had enough knowledge and perspective to know that the people and politicians on television lied, ridiculed us, and hated our people.

In Southern college life I also observed that all the numerous student revolutionaries who came from outside were shallow, self-centered, and had no real experience of the “poverty” they came to liberate us from. I think it was this combination of experiences that turned me into a historian and a Southern one.