Among the various moral reform and benevolence movements in the Jacksonian Era such as temperance, antislavery, prison reform, and the peace movement, one of the lesser known efforts sought to improve the observance of the Christian Sabbath, or the Lord’s Day. Both terms were used in the nineteenth century, the former preferred by Presbyterians and the latter by Baptists, and they were understood to refer to Sunday, the first day of the week. From New Testament days, Christians had observed the first day of the week as a day of corporate worship in remembrance of the resurrection of Christ. Those schooled in Calvinism or that subscribed, as did Presbyterians, to the doctrinal standards of the Westminster Assembly that met at the English Parliament’s request in the 1640s, also observed the first day of the week as the weekly Sabbath in obedience to the Fourth Commandant, to “Remember the Sabbath-day to keep it holy.”

The importance of the Sabbath as an institution in early America has been but dimly understood. One late twentieth-century scholar, Winton Solberg, depicted the Sabbath as a pillar of eighteenth-century culture not only in its stronghold of closely-settled New England but also throughout British North America. In most of the Southern colonies, the relative weakness of the Anglican Church and a dispersed population lessened the Sabbath’s significance. But even in the tobacco colonies of Maryland and Virginia, the Sabbath represented, in Solberg’s words, “an island of rest in an ocean of endeavor,” a characterization still somewhat applicable to the Upper South states of Virginia, North Carolina, Kentucky, and Tennessee in the early nineteenth century. After the colonies achieved independence, traditional Sabbath statutes generally remained in place and held cultural importance even though infrequently enforced. At least 23 of the 24 states that comprised the Union in the 1820s maintained some form of Sabbath statute, in addition, in many cases, to local ordinances that typically restricted business and even recreational activities. For the faithful, the day provided set times for collective religious worship, instruction, and fellowship. Even for non-participants in organized religion, the day offered a regular opportunity for family or other social gatherings and rest from labor. For many Christians, Sabbath laws and Sabbath observance identified the United States as a “Christian nation.” Some took comfort in the fact that although the U.S. Constitution did not explicitly acknowledge God or His providence it did acknowledge the Sabbath by excepting Sunday from the ten days allotted to the president to sign a bill into law or to veto it. And throughout the federal government, no business was conducted on that day. The lone exception was actually the largest department by far in the federal government, the postal department.

Much of the impetus for Sabbath reform activity from 1810 to the early 1830s stemmed from the little-known Post Office Act of 1810 within the context of the beginnings of a revolution in the means of transportation becoming available to many Americans by this period. Sabbath-promoters argued that the federal government disregarded God’s moral law with the unnecessary transportation of the mails and the opening of post offices on the first day of the week. But, in addition, the completion of the Erie Canal in 1825 and others of lesser consequence in conjunction with increasing numbers of steamboats and macadamized roads as part of a Market Revolution gave ordinary Americans greater opportunities to set aside traditional Sabbath restrictions on travel and the conduct of business and recreation. If some were troubled by conscience, they had only to reflect that, in most cases, the only local representative of the federal government, the postmaster – a man respected in the community – had set the example of conducting secular business on the Sabbath at his post office. The primary objection to the postal law that in turn fueled various Sabbath-promoting activities was the fact that the law required post offices to remain open on any day of the week on which the mails might arrive. That included Sunday if for no other reason than the irregularities and delays of post riders’ and mail stage coaches’ schedules that could, and did, result in Sabbath day arrivals.

The 1810 postal law has been referred to by historian Richard John as the first federal law that required particular behaviors on the part of certain citizens throughout the nation. Thus it marked a transition, slight and innocuous at the first, both in terms of the exertion of federal authority and the relationship of the federal government to the United States, a designation understood in that era as plural rather than singular. Although many comprehensive, sometimes lengthy, written communications regarding Sabbath issues originated in New England or the mid-Atlantic seaboard states, many Southern editors disseminated such ideas and arguments in mainly denominational newspapers and periodicals. Some of those addressed the relationship of the Christian Sabbath with civil liberty.

The Calvinistic Magazine, published in Rogersville, Tennessee, by local Presbyterians, provided such examples. In October 1829, its editors published an extract of a previously-published essay by one Judge Baird on the transportation of the mail on the Sabbath. While Baird’s original title focused on the transportation of the mail, the Calvinistic Magazine tellingly began the essay with its own introduction under the title, in bold lettering, “State Rights, or the Question Settled.” The first paragraph of the issue’s lead article honed in on the Constitution’s denial to “the general government, the power of ‘prohibiting the free exercise of religion,’ among the citizens of the several States.” The Presbyterian editors pointed out that the states had enacted laws prohibiting their citizens from engaging in “secular business on the Sabbath.” “Now, has the general government a right,” they asked, “to require a number of the citizens of each State, to trample the State laws under foot? But this is done in every case where a Post Master, or Mail Carrier, is required to perform the duties of their office on the Sabbath; for each Post Master and Carrier is a citizen of a State, whose laws forbid it.” The editors continued, “If the general government may require citizens to violate the laws of the State in one case, it may in another; – and who can tell where these encroachments will stop?”

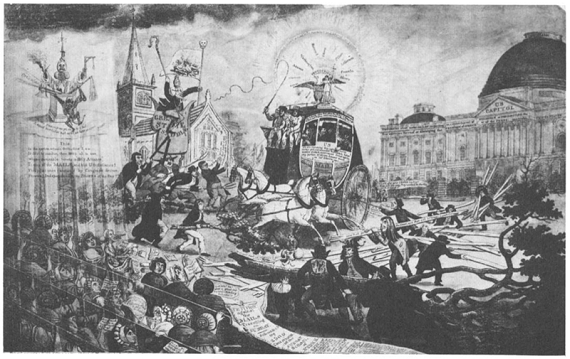

In the extract of his essay that followed, Baird dealt with the First Amendment including its free exercise of religion clause. He observed that the act in 1789 that established the judicial courts of the United States explicitly precluded court sessions from commencing on a Sunday. But contrary to that example, in recent years the general government had interfered regularly with the free exercise of religion of thousands of post masters, mail carriers, and citizens “in a manner the most injurious and the most extensively felt, that could have been devised; by driving the mail stages on that day, upon all our great roads; through the streets of our towns, and often past the doors of our churches, where congregations are engaged in divine worship.” While the postal employees were injured religiously in terms of having to labor and thereby being deprived of the privilege of Sabbath day corporate worship as well as rest, many worshippers experienced the disruptions of mail stages that Baird and others described. Thus, Tennesseans and subscribers to the Calvinistic Magazine from several other Upper South states were informed of the ongoing violation of the First Amendment’s religious clause in connection with Sabbath mails.

During the 1820s and 30s, sermons and other publications addressing the importance of the Sabbath and the threats to its continued influence in America flowed freely from the pens of Northern ministers and moral reformers. Only a handful came from Southern divines, including two sermons apparently written for publication rather than for oral delivery by the president of East Tennessee College in Knoxville, Dr. Charles Coffin. While spiritual concerns were foremost for churchmen that dealt with Sabbath matters, like his peers Coffin also addressed secular issues including civil and religious liberties. He viewed the desecration of the Sabbath on a national scale as portending the loss not only of civil and thus religious liberties but as leading inevitably to “immorality and outrage, violence and murder, discord and misery.” Coffin opined that when “violations of the Sabbath have become so prevalent as to contaminate the moral character of a nation, they make some of the most grievous afflictions of the church and people of God.” “[T]he inevitable consequences of prevalent sabbath-breaking,” warned Coffin, “are some of the heaviest curses a nation can experience.” For the Presbyterian minister and his peers, as well as some laymen and non-church members, the loss of civil and religious liberties precipitated by widespread Sabbath profanation was tantamount to the destruction of “all that is pure in religion and valuable in society.” That the consequences of national Sabbath violations should be so drastic stemmed to a degree from the Calvinist understanding of America’s covenantal relationship with God. Because of this relationship, Coffin could readily affirm, “As [nations] treat the Sabbath, God will treat them.” For Calvinists, represented by both Presbyterians and many Baptists in the Old South, the warning was especially fitting for the divinely-favored and republican United States.

During two periods between 1811 and 1831, citizens throughout the nation expressed their regard for the Christian Sabbath in the form of petitions, or memorials, to Congress. The second, larger effort took place between 1828 and 1831 in which hundreds of petitions were sent to Congress, the vast majority of them requesting the national legislature to repeal that portion of the postal law that required the violation of the Sabbath by the transportation of the mails and the opening of post offices. While the majority of petitions hailed from New England and the mid-Atlantic seaboard where Congregationalists and Presbyterians were the leaders on the issue, a significant minority of the documents were signed by citizens from the Southern states of Virginia, Kentucky, North Carolina, Tennessee, and South Carolina, with Virginia and Kentucky supplying the greater numbers. While in many cases the petitions were mass produced and – employing the very postal system that was intended to be regulated, distributed to local leaders in various towns – a fair number resulted from local initiative in various Southern communities.

One of the best of these was from Greene County, Tennessee, traditionally a Presbyterian stronghold on account of the many Scots-Irish that had settled in the eastern part of the state. Many local petitions were handwritten, including one from Greene County in the winter of 1828-1829, but another one a year later was machine-printed on a single large sheet. Entitled, “Memorial From Tennessee, On Sabbath-Mails,” the petition was signed by nearly 130 individuals, making it one of the largest such documents from the South and probably the most professional. The petitioners offered five reasons for their request, the first addressing the similarity of the postal law with the “odious” Test Laws of England. The Greene countians, including locally prominent Presbyterian ministers Samuel W. Doak and Francis A. McCorkle and at least two other men connected with the Presbyterians’ Greeneville College, believed the existing postal law violated “the rights of conscience” of those that respected the Sabbath commandment. The petitioners asked rhetorically if there was a difference “between the case of one who is excluded from office because he will not do an immoral act at the threshold,” as in the Test Laws,

and one who is excluded, because he cannot discharge the duties of the office without doing what he esteems an immoral and sinful act? The exclusion in both cases is effected by the same means; and is, in both cases, equally injurious to the citizen. . . . The person who thinks it criminal to profane the Sabbath day, is as effectually excluded from the profits of being Post Master, or Stage Contractor, as if a test were required of him, which, as a conscientious man, he could not take. . . . Is this right? Is it just?

In addition to pointing to the rights of conscience, the Greene County memorialists addressed another aspect of civil liberty in their second argument, similar to that mentioned in the Calvinistic Magazine. They declared,

Your petitioners consider the before-mentioned laws as . . . trampling under foot, the laws of the respective States. The State of Tennessee, in common with most, if not all the other States of the Union, has enacted laws to prevent the profanation of the Sabbath. That . . . Tennessee had authority to enact such laws, will hardly be disputed. Neither can it be controverted that the laws of the United States, authorising the mail to be conveyed, and requiring the post offices to be kept open on that day, are in direct violation of the State Laws, and bring the authority of the States, and the United States, into collision – a state of things greatly to be deprecated.

In 1828 a national Sabbath society had been formed in New York, and a number of local societies were organized in Northern states as auxiliaries to the General Union for Promoting the Observance of the Christian Sabbath. In the South, however, only a few such societies seem to have been formed. Perhaps the most significant was the Virginia Society for Promoting the Observance of the Christian Sabbath. In one of the Virginia Society’s first declarations, in 1831 its corresponding secretary, William F. Lee, wrote, “The Sabbath lies at the foundation of Christianity, and is essential to the continuance of all our civil and social blessings. Without it, Christianity and our free institutions must be swept from the face of the earth.” The Reverend Lee’s expression was typical of many Sabbath promoters North and South; and was as concise as any in uniting the religious and civil benefits that flowed from the weekly institution of the day of rest.

A year later, the Convention of the (Episcopal) Diocese of Virginia recommended to Episcopalians the adoption of a pledge promoted by the Virginia Sabbath Society. In part, while promising to abstain from various forms of Sabbath profanation, the pledge identified the Sabbath with the “social, civil, and religious interests of men.”

Although undated, a short pamphlet published in the 1830s by the Virginia Society was addressed not only to Virginians or Southerners but “To the People of the United States.” In the middle of the seven-page pamphlet one paragraph addressed the place of the Sabbath during the constitutional formation period. The unknown author stated that “our civil authorities have always recognized the first day of the week, as a day of rest” and that this was “from the first settlement of the country; and by the State governments before, and at the time the constitution was formed, from which the Federal government derives its powers.” He continued, “It was plainly not the intention of its framers to give the Federal government any power to interfere with an institution,” meaning the Sabbath, “which had been long in existence, and was deemed by the great body of their constituents of vast importance.” Yet the post office law, “requiring the transaction of business in that department every day in the week, does, to a certain extent, abolish the Sabbath. And as the constitution confers on the general government no such power, the enactment of this law was unconstitutional.” Although the original design probably was not to this end, the necessary consequence of this single law was to deprive thousands of citizens nationwide of one of their most fundamental civil liberties, that the first day of the week remain undisturbed as a day of rest from labor generally, and for many, also as a day of corporate worship.

Although Sabbath petitioners and promoters typically were respectable men in their communities, in time they were subjected to harsh verbal treatment by their opponents. One leading newspaper, Niles’ Register, in February 1829 suggested that “the history of legislation in this country affords no instance, in which a stronger expression has been made, if regard be had to the numbers, the wealth, or the intelligence of the petitioners.” But by 1829-1830 the so-called Sabbatarians were receiving verbal attacks from opponents many of whom mischaracterized the nature of their grievance. In counter-petitions, anti-Sabbath gatherings, and one well-known U.S. Senate report issued under the name of Richard Mentor Johnson of Kentucky – the supposed slayer of Tecumseh at the Battle of Thames in October 1813 – but actually ghost-written for him by the Baptist minister, Obadiah Brown, with whom he roomed in Washington, Sabbath-promoters were at times charged with attempting to ‘unite Church and State’ and were likened to Judas Iscariot, Benedict Arnold, and worse. In the face of such opposition, the Congress made no change to the postal law, and by 1831 most Sabbath-promoters wisely saw the futility of further petitioning efforts. Presciently summarizing the danger to Americans’ civil liberties posed by the federal intrusion into the states’ regulation of the Sabbath, in 1829 the Calvinistic Magazine may have put it best: “Let the people of this nation look to this, and remember, that religious liberty may be destroyed, under the specious pretext of defending it.”