This essay appeared in the 1984 winter issue of Southern Partisan magazine.

In the best of all possible worlds, President Reagan, George Will, William Buckley and I—conservatives all—or so it would appear—should be able to sit down over glasses of sour mash and find ourselves in such sweet agreement on the range of problems facing the world and the humankind in it that any opinion one of us stated might by and large draw nothing more than approving nods from the others.

But as most of us are constrained to notice now and again this is not the best of worlds, possible or otherwise, and the notion that conservatives east, west, midwest and south will find themselves in agreement on most matters of policy —much less on specific applications of policy—amounts to sentimentality, if not downright delusion.

The truth is that the very notion of conservatism differs—on some points radically—between various regions of America. Surely no one expects or wishes there to be a conservative creed on the Nicene model with an appropriate place at the bottom right-hand side for individual signatures. But the nagging question arises from time to time as to how much those who reckon themselves to be conservatives in various areas of the country actually have in common.

In recent months, for example, President Reagan’s stationing of Marines in Lebanon without a clear-cut combat role, a mission to achieve, has made me question whether his conservatism and mine hold the same view of the use of military force. My view is simple and founded purely on Roman principles: Avoid battle whenever an interest or purpose can be obtained by other means, political, diplomatic, or economic; fight only for clear-cut interests which can be won or preserved by force; fight when and where you will be able to achieve a determinable victory. If you engage, win—at whatever cost— and make sure the enemy suffers disproportionately greater loss than you do. I cannot say what the President’s view is.

Again, in a column written some months ago with regard to the nomination of a noted Southern academic as executive of the National Endowment for the Humanities, George Will attacked the nominee in a manner better suited for fulminations against Mao or Stalin. The gravamen of the man’s offense: He had written a scholarly article on the proposition that Abraham Lincoln was a chiliastic Gnostic, caught up in the crazed visions and rhetoric generally associated with the likes of Bakunin or John Brown. A man who could thus view Lincoln obviously was unfit for such a post as head of the NEH.

Horsefeathers! As a matter of fact, I did not agree with that evaluation of Lincoln—and so informed the distinguished scholar in question long before Mr. Will saw his paper. For my part, I would as soon the term “Gnostic” remain in the technical vocabulary of philosophers of history and not become one more useless term of insult on the order of “Fascist” and “Communist.”

But Will’s stance comes close to requiring a loyalty oath to the Great Emancipator, and I for one will not have it. It is one thing to live one’s life under the necessity of empirical events long past; it is quite another to be forced to genuflect to them. If I cannot agree to Lincoln’s being a Gnostic, I have no great affection for the man under whose aegis my nation was destroyed; nor would I temper my observations regarding him either to please Mr. Will or gain a post dependent upon political patronage and denial of my own historical past.

My problem with Mr. Buckley is far less specific. It is more in the way of what Henry Kissinger likes to call “atmospherics.” I do not care for the Ivy League mentality; nor have I much use for what a newsmagazine called a few years ago “The American Aristocracy.” This is not a working-man’s prejudice—though I share a number of those. It is more specifically an anamnesis, a recollection that the American nation—back when it belonged to all of us— had to do with a certain hard-nosed intelligence, an openness to experience, a limited but real sense of classical past and a profound respect not only for institutions in place but for the work of a man’s hands and mind as well as a deep and unshakeable certainty of the role of divine providence in the affairs of humanity not to mention a profound contempt for inherited title, place and dignity.

There is, thank God, despite the media flacks, no American aristocracy because the only concrete thing that passes from generation to generation is money and it may well be that law permits altogether too much of that to pass on.

I do not dispute Mr. Buckley’s implicit high valuation of style, and few derive more pure malevolent pleasure from his writing when he takes off on Galbraith or Schlesinger than I do. But I cannot overcome the sense that, at last, Mr. Buckley will give the world for wit, and while that may pass for a polity in the farther reaches of Westchester County, I incline to more substantial fare.

But enough carping on what, taken together, do not constitute substantive points of disagreement. We would do better to suggest, even though in barest outline, what I take to be some of the foundations of a conservatism that would involve traditional Southern thought and sentiment. Beginning with…

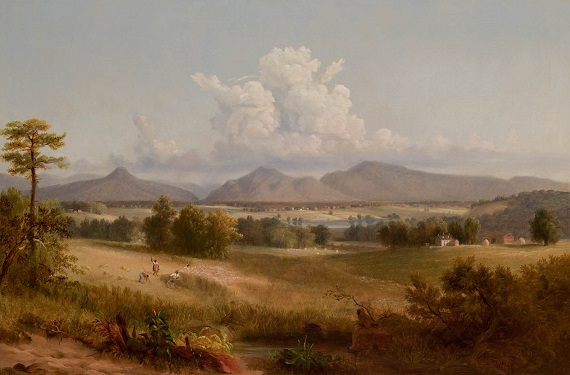

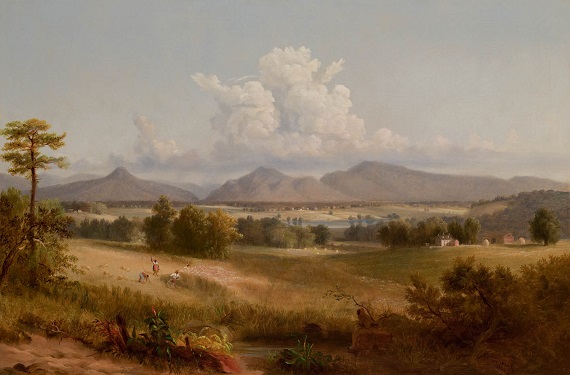

The Land. I have always supposed that Clifford Dowdey was the wisest of Southern historians because he named his one-volume history of the Confederate War, The Land They Fought For. Dowdey knew what Faulkner knew when he wrote the monumental introduction to his collection of stories, Big Woods. We fought then— and would, even now, fight not for a political ideology or a manner of distributing goods or some damned fool got up to look like Mussolini or Castro— but for this place, this soil, this South. My South is Louisiana and East Texas. That is where, in the phrase of Professor Eric Voegelin, I had my “primary experience of the cosmos.” In the swampy fingers of Bistineau or Blue Lake, on the Tchefuncta River in St. Tammany Parish, I have drifted for hours in the loving tension called bass-fishing.

It was there on a dateless late summer afternoon in an anonymous cut-off playing out a fly-line that I came to realize I could not hold with St. Paul as to the fallenness of all creation. On that day, amidst that incredible richness and verdancy, poised in a bateau over literally wine-dark water, I saw that the world was good, as it should be, in the awful burgeoning rhythms and polyphony of life and death. That which was in conflict was in agreement with itself. The only entity capable of sin or crime or cruelty or of that great Greek failing, Harmartia, “missing the mark,” was… me.

That slight crispness at evening in September or October that tells of the year’s ending. The chill distant beloved stars on a winter night when a Norther has just blown through; those first leaf-buds we look for and find in March while Minnesota and Vermont are still tranced in deep snow-encrusted slumber; the searing heat of August, its silence, its incredible fecundity that makes one question, experience aside, whether there will ever be another autumn; the rise and fall of the pine-covered North Louisiana land around Nachitoches; the soaring oak and magnolia and cypress and sycamore and cottonwood and sweetgum of the lower Parishes; the vast and unplumbable slash of the Atchafalya swamp that comprises the instep of the Louisiana boot—all of it and the sweet sky above are where I begin any and every investigation of physis or psyche, because for me, it all starts and will surely end with the land.

Concretely, then, when President Reagan, while still governor of California, observed that when you’ve seen one redwood tree, you’ve seen them all, I cringed. I have been in Marin County and walked amongst the redwoods. I did not see one that resembled another, and surely not one I would gladly hand over to destruction, to be made into picnic tables or fence-planks.

Acknowledging the imprudence and falsetto militancy of the “environmentalists,” and the need to provide jobs for human fold in forest and wetlands industries, a Southerner cannot, I think, shrug at a fish-kill or ignore the destruction of a shoreline or the death of a lake from acid rain. Because, despite all the shoddy PR-mongering of “Sunbelt” prosperity and condominium-constructing and paving over good farmland for a Seven-Eleven parking lot, (the very gaucheries Thomas Wolfe attached with such force in regard to his home town of Asheville, North Carolina in Of Time and the River) somehow, in some almost-forgotten zone of the soul, to be a Southerner at all calls for a remembrance of what the land has always meant to us, the price our fathers and mothers paid for it—in something other than U.S. legal tender and that “primary experience” most of us from small towns and cities can recall if we close our eyes and recollect.

The Community. The second stratum of human existence that one comes to be aware of is the community. On the land, we live in immediate communion with others. These others will be like us and unlike us, and we will live and grow in terms of the similarities and the dissimilarities as well. We come to understand the distinction between those differences between people which accord with the community’s ongoing life, and those which do not.

We learn that every difference is not a crime—and that every crime is not necessarily founded in a difference. We discover a balance of equities in the town or city we live in—or the need for such a balance if the place is to be well-ordered. We find that there is religion—and religiosity; ambition— and greed; a sense of decency—and prudery; a desire for law—and an urge to dominate; a profound love and respect for the past—and sterile nostalgia. We come to realize long before we are grown that the diversity of America, even in a small Southern city, requires a certain kind of sensibility if one is going to be happy and productive and in resonance with the deepest sources of his own being.

When a synthetic community—and every gathering of Americans is that— cannot come to terms with itself, it will be ruled from outside. That is what befell Southern communities in the 1950s. Concrete federal power and abstract federal theorizing, using the occasion of real racial injustice, became a central force in every city and town, and in virtually every aspect of community life. Federal hypocrisy and State hypocrisy met head-on, and the big loser was the very sense of community itself. For, the necessary administration of constitutional justice became the cover for a radical trans-formation of community reality, a transformation which seems to have even slipped the control of the general government which initiated it.

In Clarksville, Texas, aged blacks and whites have been forced to move between two local public housing projects so that the number of whites and the number of blacks in each projects will be equal. Never mind that both groups protested, and that there were no exclusory laws or enforced practices on the Texas or Clarksville books: It will be done, and it has been done, and none of the apparatchiks of government gives a damn how many elderly people have been rendered unhappy or uncomfortable by their own diktat.

Clearly, the outside forces which came to correct the disorder of long-practiced and engrained racial injustices have themselves become the forces of disorder at the level of actual concrete human life.

There is no mystery in this: Rule from a distance, by people having no part in the community, constitutes tyranny de facto. Not because the rulers are ill-intentioned, but because they are ignorant of the delicate tuning of each distinct community, and at last have no interest in it. Rule from a distance is abstract rule; the persons ruled become counters, pieces on a board called Politics. There are good pawns to be assisted, evil pawns to be thwarted, and the means of doing both are, of necessity, statistical.

Another example of the same debauchery of governance is the treatment of the Mormons a century ago in relation to polygamy—or the more recent mistreatment of the Amish with regard to their schools and educational practice. It is diverting to discuss “the larger American community,” or “the global village” but it is mindless to think and act as if those entities really exist in the world and even worse to make use of personal opinions derived from those imaginary things as authority for demolishing or distorting actual human relations. It is one thing to hold that no man should be excluded from a community because of his race or religion; it is another to force human beings into artificial relationships which they neither seek nor desire.

A community is a concrete array of human beings who voluntarily live and work and fail and succeed and love and die in participation with one another with a degree of propinquity and intimacy that links their destinies in a substantial and immediate way. Thus any black citizen of Louisiana or Texas or Mississippi more nearly participates in my community than any white resident of Wisconsin. The “intellectual community,” the “cultural community,” the “work-related community,” for all their relevance in a constantly shifting population, do not possess the degree of reality inherent in a community of human beings living together in Tyler, Texas, or Meridian, Mississippi.

Americans, whatever their situation, are not “the masses” of Marxist-Leninist speculation. They are the people of the Preamble of the Constitution, or of the Gettysburg Address, and politicians of the stripe of Jesse Jackson who insist upon referring to them as “the masses” are, likely, over time, to discover the difference. The term “masses” is a direct reflection of nineteenth century materialist rhetoric in which human beings are to be regarded as impersonal entities on the model of classical physics. One uses “force” on “masses” as any scientistic dolt knows. One reasons with, persuades, enters into debate with fellow human beings. People have minds and hearts and souls. They are unpredictable, and those who lead them have to take into account the changing character of the peoples’ self-interpretation. “Masses” have no more character than billiard balls: One aims them, strikes them, and they go where they are sent. With matter, force is the first and only means of dealing; with human beings, it must be the last. I think many Southerners are not satisfied with the quality of insight that the present administration has brought to such questions. It is not that the positions are wrong. It is that there seems to be little force behind the positions held, and hardly any new thought or insight at all. Surely, when one hears liberal candidates speak nowadays, it is as if one has entered a Museum of Antiquated Political Ideas, dropped a quarter in the slot, and is listening to the Roosevelt doll going on and on with notions fresh from 1933.

But national conservatives have failed utterly to rearticulate their values in terms of the new contingencies or to find adequate symbols for their expression. Thus the present political debate sounds as if it were taking place within the same museum, the Hoover doll quacking back at his equally vacuous opponent.

Contemporary conservatism at the national level is at least as much a product of corporate interest as of personal principle, and it may be there that Southerners part from the “conservative mainstream.” Most of us, I think, are not given to the corporate mentality. If we are working men, we are, most of us, not devout unionists; if we are businessmen, we tend to be small businessmen, and not overly interested in franchises with 3,000 restaurants serving hamburger that tastes like flannel and eggs scrambled late yesterday. We incline to think that homogenization is all right for milk but downright lethal for people, and we view collectivization as a disgusting aberration of demoralized mobs in failed communities—elsewhere, not here.

“Collective,” like “masses,” is a word with strong mechanical overtones, and we have little use for such words or such concepts. We prefer “family,” or “neighborhood,” and a collectivizing IBM or Texaco is not much more to our liking than a collectivizing socialism.

The closer a man is to that primary experience of the land and the water in its solitude and its majesty, the less he is inclined to suppose that his relationship with the community, important as it is, can or should be the ultimate determinant of his life and its meaning. Neither his neighbors nor his job nor his numerous other affiliations should threaten to strip him of his own personality, and when the concerns of the body politic look like becoming the interests of the political corporation, most Southerners become uncomfortable. I have never believed that what was good for General Motors was good for America, and nobody I know believes that, either.

The World. Surely no man in his right mind who has argued the right and wrong of alien things in a Bossier City bar will presume to enunciate a “Southern view” of foreign policy. Except perhaps to observe that there remain a few antique verities stretching from President Washington’s Farewell Address to the Monroe Doctrine and that, given the great sea-changes of the past two centuries, the principles must be reviewed, reinterpreted in the light of eclipsed monarchies and the rise of a Russian empire bound together by force.

I have never held with the policy of “containment” of Soviet ambitions, because an international illness is not best treated by trying to see that it gets no worse. I do not recall that our liberal predecessors argued for the “containment” of National Socialism as it ravaged Europe in the late 1930s and 40s. They rather demanded a “popular front,” and more or less got it. Had we stood for “containment,” such a policy would, I think, have drawn a line at the edge of the Western Hemisphere and let Europe—and Asia—for that matter, suffer what they must while the Nazis and the Marxists battered each other into rubble. We were not, even before Pearl Harbor, quite calculating enough for that.

The policy many of my neighbors seem to subscribe to is one that would declare our unremitting hostility to and refusal to accept as a permanent feature of the international order a political regime of terrorists and thugs along with their vicious epigones in Eastern Europe who came to power through slaughter, who maintain their control by violence, imprisonment and deceit, and who fear an honest, open election as Dracula fears the cross.

Obviously, direct military force to attain specific political goals is not among our options. We waited too long, chiefly because of the naivete of a generation of liberal oafs who supposed somehow that Stalin was a statesman, that the purge trials of the late 30s represented “people’s justice” against crypto-fascists, that the liquidation of the POUM in Spain and the murder of Trotsky in Mexico City amounted to the “regularization” of leftist affairs under the threat of National Socialist Germany.

In any case, the military option, even if it were realistically available, would not be prudent. If the American sense of political reality vis-a-vis the Soviet Union is to be respected, the struggle should be carried out at the level of reality which Marxist-Leninism claims as its own—that of political economics. The inherent paranoia of the Russian nation has, again and again, tipped dominance in the state toward Bonapartism and every such tilt produces further distortions in the Soviet economy. Absent the input of western technology, western food, and vast sums of western credit—guaranteed, at present, by you and me—the Russian empire would, in time, find itself pressing the last drop of economic usefulness out of the poor befuddled bodies of its subjects. And then, the real possibility of a counter-revolution—or evolution—on the model established by China in the last several years.

On the other hand, one is obliged to suggest that if the USSR is the most dangerous source of evil in the modern world, it is by no means the only one. I think we do ourselves and our neighbors a continuing disservice in failing to require a certain minimum standard of conduct of those who claim to be our allies. One is humbled to have to concur with the observation of a journalistic pestilence the likes of Anthony Lewis, and yet, symbolically at least, one tends to agree that the military operation in Grenada might well have been matched with a similar visit to Haiti.

I think we are trapped between the peculiar polarities of our idealism, our greed, and our bedrock indifference to the affairs of the rest of the world and, so entangled, our policies are neither forthright nor, it seems, intelligible— even to ourselves. One need only con-template the bewildering shifts of attitude on the part of the present administration toward Israel in the past two years to illustrate the point.

At last, ignoring the blistering problem of immigration policy, the profound question of just where we mean to stand in regard to our Latin neighbors, what natural interests and role we wish to evolve in Asia (aside from chronically unbalanced trade), and what response we might contemplate if, under Soviet pressure and atomic hysteria, the nations of Western Europe ask us to remove our missiles, I think a foreign policy my neighbors and I would approve must be based in decency and common sense. It must recognize the value of cultures vastly different from our own—cultures that are likely to stay that way because they prefer it. It must, at the same time, press genuine and legitimate American interests with less bombast and more effectiveness. It must reward our friends, punish our enemies—and stand ready to accept the transformation of the latter category into the former whenever that seems a realistic possibility—as, one hopes, in the case of China.

I think Southerners do not deny the complexity of modern politics, but I reject the premises of any politics which ignore the various strata which compose the personal reality of concrete human beings. It is likely true to say that geopolitical facts cannot be dealt with as a justice of the peace deals with a neighborhood quarrel. At the same time, a politics which ignores the land, the community, and the world at the elemental level where all human beings experience it runs the risk of fabricating a vision based on second realities—on mere doctrinal fixtures and faddish views that do not penetrate back down to the inescapable realities of human life and which, tor that very reason, neither convince nor encourage those who are expected to live by them.

To most Southerners, conservatism refers to the values implicit in veneration for the land, respect for the legitimate rights of all members of the community, and a realistic, non-ideological orientation toward the rest of the world. What is it we seek to conserve? Not ephemeral forms which cannot be preserved, but those relationships which transcend the forms and must be articulated anew within the existential circumstances we find ourselves.

My problem with what passes for conservatism at the national level today is that, rhetoric aside, I do not see the values that concern me at the root of policy and decision-making. Nor do I see an openness to the realization that the substance of values must be sought rather than assumed. A program initiated as “liberal” may, in time, have come to have positive usefulness within a presumably “conservative” context. Conversely, institutions historically understood to foster conservative values may have become radically destructive of them. An example of the first, given the problem of structural unemployment, is a “full employment” plan; an example of the second, given the rise of global conglomerates, might be the contemporary corporate structure.

As things stand, it is likely that most of us will support the Reagan administration in 1984—since, as Churchill said in regard to the democratic form, “All the others are so much worse.” But not with glowing enthusiasm, and with no presumption at all that eight years of “conservatism” will bring us much closer to reassertion of those values which, as Southerners, we continue to cherish.

One Comment