Today, as it was a hundred and sixty years ago, America stands on the edge of an ever-widening chasm of cultural, ideological, political, racial and sectional divisions. In 1860, there was at least one prominent voice of reason that cried out to end the nation’s mad rush into the abyss, that of Charles Mason of Iowa. Mason was a Northern Democrat who not only understood the conflicting issues that were then pulling the nation apart, but reasonably viewed the rights and wrongs of both secession and slavery, as well as strongly opposing Lincoln’s invasion of the South to militarily force the departed States back into the Union. Like many others in both the North and South, Mason did not approve of secession, but felt that as there was nothing in the Constitution to bar a State from abrogating its contract with America and peacefully withdrawing from the Union, that it was solely a matter for the people of each State to decide on their own. His fervent hope though was that if secession did become a reality and a new Southern nation created, that the two countries could then begin to negotiate their differences in a peaceful manner, somehow resolve them and ultimately reunite.

Likewise, while he strongly opposed the institution of slavery, Mason also felt that since its practice did not violate the Constitution, was still legal in almost half the States of the nation and that the matter of its abolition was not within the authority of the Federal government, that it must also be decided by the people of each State. Even President Lincoln advocated such a course as late as 1862 when, in his annual message to Congress, he proposed a Constitutional amendment mandating that slavery remain in place no later than 1900. Lincoln stated that this would allow each of the slave States up to thirty-seven years in which to decide how to abolish the institution on their own.

There is also little doubt that Mason viewed the war that did ensue to be one designed to coerce the departed States back into the Union and considered it to be unjust, unnecessary and Constitutionally illegal. He also considered the South’s action to be neither rebellion nor treason . . . and certainly not one in which the South was taking up arms to defend the institution of slavery and the North invading the South to free the slaves. Even in regard to those in the South who were opposing the Union forces on the field of battle, Mason was even-handed. Such thoughts were clearly stated in his wartime diary when he wrote about such Confederate leaders as Robert E. Lee. In mentioning Lee, Mason said that he was “winning great renown as a great captain.” He also agreed with British writers who were then comparing Lee’s generalship with that of Napoleon and Wellington, and he certainly would be appalled by today’s charges of racism and treason that are being hurled at Lee and the tearing down of his monuments.

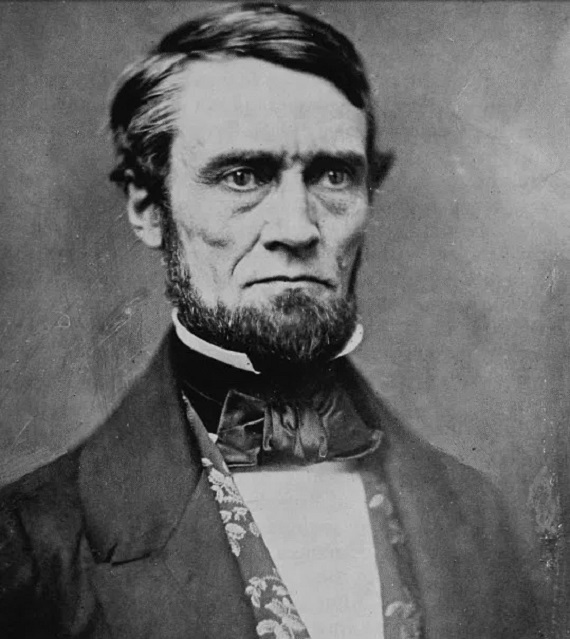

Who then was this man whose voice of reason is so desperately needed today? Like some of my own ancestors, Charles Mason’s were true Yankees who came to America from England and landed in the Massachusetts Bay Colony only a few years after those who initially arrived in Plymouth in 1620 aboard the “Mayflower.” Mason’s first American ancestor, Robert Mason, was born in the Massachusetts colony’s village of Roxbury in 1631, and his descendants, like mine, later moved westward, first to Rhode Island and Connecticut and then on into upstate New York in the late Eighteenth Century, finally settling in Onondaga County just south of Lake Ontario. There Charles Thomas Mason was born on October 24, 1804, in the village of Pompey.

In 1827, Mason received a Congressional appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point and graduated at the top of the Class of 1829 with the highest number of points ever gained by any cadet at the Academy, 1,995 1/2 out of a possible two thousand. That class also contained three young Southerners who would go on to become leaders of the Confederacy, Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee and Leonidas Polk. Lee was his closest rival in that class, finishing second with just twenty-nine fewer points. Both Lee and Mason also graduated without receiving a single demerit, but while Lee would soon gain glory on the field of battle in the Mexican War and was ultimately offered command of the Union Army just prior to Virginia’s secession, Mason attained his fame as a civilian.

After graduation, Mason remained at West Point for two years as an instructor of engineering before resigning his commission to study law in New York City while working as a writer for the “New York Evening Post.” After passing the bar examination, Mason practiced law in Newburgh, New York, until 1836 when he headed west to Des Moines County in what was then the Missouri Territory. There he became an aide to Territorial Governor Henry Dodge and then appointed as the county’s public prosecutor. When the area became the Iowa Territory in 1838, Mason was appointed chief justice of the Territorial Supreme Court by fellow New Yorker, President Martin van Buren, a post he held until 1847. During that time, Mason wrote a hundred sixty-six of the Court’s hundred ninety-one opinions, the most important one just a year after taking office. This was to become a landmark decision in regard to a slave’s rights, and one that remained as a national precedent until the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 and the U. S. Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision seven years later.

The Iowa case involved a slave from Missouri named Ralph who, in 1834, was allowed by his owner, Jordan Montgomery, to purchase his freedom by working in a lead mine in Dubuque, Iowa. After a few years, Ralph had failed to meet his obligation and Montgomery ordered Ralph’s arrest and return to Missouri. The matter was ultimately taken before Chief Justice Mason who ruled that since slavery had been made illegal in Iowa, first in the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 and further strengthened by the Missouri Compromise in 1820, Ralph could remain in Iowa as a free man. In his ruling, Mason wrote that “the master who, subsequently to such acts, permits his slave to become a resident here cannot afterwards exercise any acts of ownership over him within this Territory.” In other words, the rules of property, in this case a slave, cannot exist without the existence of slavery and concluded that Ralph was illegally being deprived of his human right of liberty. He also added the prophetic statement that since laws should offer equal protection to people of all colors and conditions, the present case involved an important question that, if left unresolved, could cause major problems in the near future. The ensuing two decades proved his wise words of reason to be all too correct.

When he left the high court in 1847, Mason returned to private practice in Burlington until 1852, after which he served for a year as president of the Burlington and Missouri Railroad and then was appointed by President Franklin Pierce as the U. S. Commissioner of Patents in Washington, D. C., where he served until Pierce left office in 1857 and was regarded by many as one of the most effective Patent Office commissioners of the Nineteenth Century. One of the people he employed at the Patent Office as his confidential clerk was Clara Barton, the first woman to hold a regular Federal government position with work and pay equal to that of a male employee. During the War, Clara Barton became the Union Army’s most famous nurse and in 1864 was placed in charge of all the hospitals under the command of General Benjamin Butler. After the War, she headed the U. S. Office of Missing Soldiers and two decades later founded the American Red Cross, as well as helping to establish hospitals for the German Army during the Franco-Prussian War.

Under Mason’s able administration, the Patent Office reduced the number of pending patents to about one per cent of what it had been, and continuously issued a record number of new patents. He also introduced legal measures to guard American inventions from being pirated by foreign interests, as well as establishing the system of printing patents and drawings, rather than copying such work by hand, which greatly reduced cost and speeded up their issuance. While in Washington, Mason was also named to the boards of directors of both the Smithsonian Institution and the U. S. Naval Observatory where he started a system that later became the U. S. Weather Bureau.

A year prior to his leaving office, Mason learned that farmers and merchants all across the nation were working to have him nominated as the Democratic candidate for president in the 1856 elections. While this did not happen, Mason did enter into politics after his return to Iowa in 1857 where he became an attorney, served on the State Board of Eduction and became an active worker in the State’s Democratic Party . . . so active that within two years he was nominated as their candidate for governor.

The Iowa Democrats, like those throughout the rest of the country at that time, were badly split into opposing factions, with the new Republican Party rapidly gaining strength. While candidate Mason did not question the need to keep the nation unified, he had openly and strongly opposed going to war to accomplish that end. He had publicly stated that while he did not approve of secession by the Southern States, they had a legal right to do so and that going to war to preserve the Union was wrong, if not illegal. The “Dubuque Daily Post” also reported that Mason had stated that the Federal government would be engaging in nothing more than “naked, arbitrary, down-right coercion” and that “a republic held together by the sword becomes a military despotism.” The Republicans and the Republican-controlled press immediately branded Mason a disunionist traitor, and the pressure they exerted forced him to drop out of the race for governor . . . thus insuring the election of Republican candidate Samuel Kirkwood who took office in January of 1860.

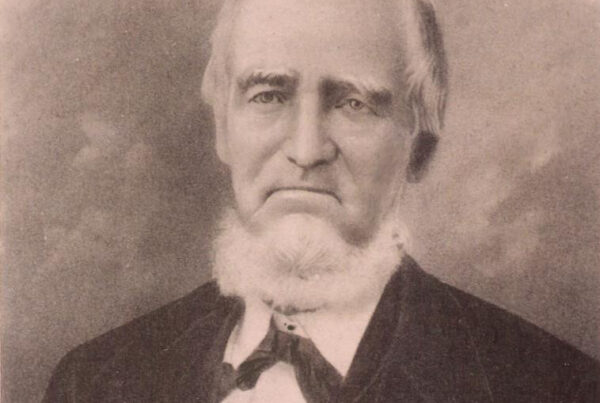

During the War, Mason remained a Peace Democrat, a group that, due the fact that their party emblem was a copper penny were called “Copperheads.” The term, however, soon became synonymous with the poisonous snake of that name, as well as a derogatory title for anyone who opposed Lincoln or the War. Mason also continued to criticize Lincoln’s actions throughout the War in local newspaper articles and organized opposition groups in Washington, as well as supporting General George McClellan’s presidential race in the 1864 elections. After the War, he again returned to private law practice in Burlington until his death in 1882, as well as engaging in a number of civic activities, including serving as president of the Burlington Water Board and the Burlington Street Railway Company, chairman of a the German-American Savings Bank and treasurer of the Burlington School Board. In 1867, Mason was again the Democratic candidate for Governor, but lost to Republican Samuel Merrill.

Sadly, Mason’s voice of reason was not heeded and the divisions that split the nation in 1860 resulted in four years of bloody conflict, leaving wounds that, to some, never completely healed. The skeletal remains of such divisions as slavery and secession have now been exhumed from their once peaceful graves and paraded before today’s howling public as targets on the current political and social agendas. While the South is again being tarred with the memory of such long buried issues, the new battles are not being conducted by armies clad in blue and gray fighting for what they both truly believed to be just causes, but rather by motley mobs from the left and right that only wish to erase history and rewrite the perceived wrongs of a bygone era. While there are again voices of reason similar to Mason’s that call out for a sane path to the resolution of the issues that once more divide America, they are either ignored or drowned out by the ignorant, screaming masses. Furthermore, many who do correctly understand the history of such divisions and agree privately with the voices of reason are all too often cowed into silence by fear of public or political condemnation and retribution.