Just before Christmas of 1860, the chain of events that was to soon to lead the nation into four bloody years of undeclared war began with South Carolina exercising its constitutional right to leave the Union and revert to its original status as a sovereign entity. Six of South Carolina’s neighboring States quickly followed her out of the Union and on February 22 the following year, these seven independent States reunited in Montgomery, Alabama, as the Confederate States of America. Unwilling to recognize either this right or the new nation, the Lincoln government issued a call for all the twenty-six States remaining in the Union to raise an army of seventy-five thousand men to quell what Lincoln termed a rebellion. Arkansas, North Carolina, Tennessee and Virginia, all of which had initially voted against secession, refused the Union demand to supply troops for the invasion of their sister Southern States, seceded and joined the Confederacy. Filled with unfounded fear of an imminent Confederate march on Washington, the Federal government ordered troops be rushed to the nation’s capital for its defense. The day after Virginia’s secession on May 24, thousands of these “defense” forces made up of numerous infantry, cavalry and artillery units and led by Major General Charles Sanford of New York poured over the Potomac River bridges in an unprovoked invasion of the surrounding areas of Virginia and quickly occupied cities such as Alexandria and Arlington, with Sanford’s headquarters being established at General Lee’s mansion in Arlington Heights. One unit that invaded Arlington was the Eleventh New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment, better known as the New York Fire Zouaves due to being mainly made up of New York City firemen dressed in unusual Moroccan-style uniforms. Their leader was Colonel Elmer Ellsworth, a personal friend of President Lincoln, and when Ellsworth spied a large Confederate flag flying atop the roof of the Marshall House Inn, he rushed up the hotel’s stairs and tore the banner down. The enraged owner, James Jackson, killed the colonel with a shotgun blast, followed by Ellsworth’s men immediately slaying Jackson. The two were soon regarded as the first martyrs for their respective causes.

The May invasion and occupation of large areas in Virginia continued, and the military’s expanded Department of Virginia that was created that month under the command of Major General Benjamin Butler, a leading Massachusetts politician, covered all of southeastern Virginia and northeastern North Carolina. One of General Butler’s first objectives was to secure for the Union the nation’s largest fortification, Fort Monroe on an island at the tip of the Virginia Peninsula. The guns of that bastion guarded both Chesapeake Bay and Hampton Roads, as well as the numerous rivers feeding into these vital waterways and such important naval facilities as the Norfolk Shipyard. Up until the spring of 1861, the fort’s commander, Colonel Justin Dimick, with only a small number of troops had managed to strengthen the facility against any possible attack, but was not able to take any aggressive action or even protect the fort’s water supply. The latter problem was resolved when Colonel Dimick and Virginia’s Major John Cary met and agreed that if the fort’s troops made no move into the State, Virginia would not cut off the supply of fresh water from a spring a mile inland. The Union realized, of course, that such a truce could not be maintained and sent eight thousand troops by ship under General Butler to reinforce Dimick. Following Butler’s arrival, he was given orders by General Scott to leave a defense force of fifteen hundred troops at Fort Monroe and move the remainder of his command inland to occupy any artillery batteries in the area and retake the Norfolk Shipyard in Portsmouth that had been seized by the Confederates. Despite the fact that President Lincoln had told General Scott that martial law was to be established in any area taken by the Union, General Butler was given no specific orders on this matter. In the face of this action, the Confederate troops opposing Fort Monroe retired twenty miles up the peninsula and established defense lines at Yorktown. Even so, as the Union troops were mainly untrained and poorly-armed volunteers with no cavalry or mobile artillery support, there was little Butler could do in the way of mounting a major action. In June, however, Butler launched a probe towards Yorktown by two New York regiments under the command of Brigadier General Ebenezer Pierce. The force blindly ran into the Confederate defense lines at Big Bethel that had been set up by Colonel John Magruder to deter any such move. In the ensuing confusion, the Union regiments fired at each other, losing seventy-six men to the Confederate’s eight, and the defeated units hastily retreated back to Fort Monroe. This early Confederate victory embarrassed the North and helped to build up the South’s confidence, feelings that were greatly enhanced a month later with the major Confederate victory and even more shameful Union rout at the Battle of Manassas.

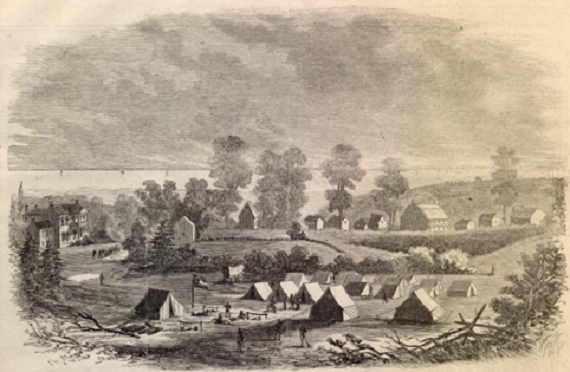

During the next few months, Confederate cavalry units raided the Union positions above Fort Monroe, including the camps at Newport News and Hampton where they torched the entire town of Hampton. The Lincoln Administration decided it had enough of General Butler’s ineptitude for the moment, and replaced him as commander of the Department of Virginia with a far more experienced military officer and administrator, seventy-eight year old Major General John Wool of New York. Wool realized the failings of raw militia troops and while he did retake Norfolk he mostly used the cavalry he had received to conduct limited actions around the Confederate lines at Yorktown throughout most of the remainder of 1861. Wool did, however, make some more aggressive moves along Virginia’s eastern shore below Maryland and Delaware, as well as using ships from Admiral Louis Goldsborough’s blockade squadron to attack Confederate defenses along the Cape Hatteras area of North Carolina. The week-long invasion of Virginia’s eastern shore began in mid-November with over five thousand troops from New York, Massachusetts,Wisconsin, Indiana and Delaware who had combat experience at either Bethel or Manassas. The east shore action met with almost no Confederate resistance and ended when units from the Fifth New York Regiment reached Cape Charles at the end of the peninsula and established Camp Felicity at Drummondtown. A proclamation from Major General John Dix’s headquarters in Baltimore was posted in the town square which stated in part that if there was no “hostile resistance or attack . . . there need be no fear that the quietude of any fireside will be disturbed unless the disturbance is caused by yourselves.” The twelve-hundred man camp maintained a tight occupation of the area with no serious incidents other than the selling of some tainted food to the camp by local citizens. The camp also served as the main facility for future amphibious moves against coastal areas across Chesapeake Bay. November of 1861 also saw a major change in the United States Army when seventy-five year old Commanding General Winfield Scott was replaced by Major General George McClellan.

Early the follow year, McClellan began making plans for a more complex and entirely different attempt to capture the Confederate capital of Richmond. Rather than a direct overland attack, such as the failed attempt at Manassas, the new commander proposed sailing the entire Army of the Potomac down Chesapeake Bay to Virginia, then up the Rappahannock River to Urbanna in Middlesex County and launching the land assault from the peninsula between the Rappahannock and York Rivers. The move to Urbanna was finally ruled out in favor of a longer land route starting at Fort Monroe and marching directly up the Virginia Peninsula to Richmond. While Middlesex County had been spared from an invasion by the entire Union Army and saw no major battles during the War, there was still quite a bit of wartime activity there. Middlesex County was an almost entirely rural area with an 1860 population of only eighteen hundred white residents, two hundred eighteen free Blacks and almost two thousand four hundred slaves, with its largest towns being Urbanna, which had been the county seat until 1852, and the new county seat of Saluda to the southwest. Many of the residents of both towns, fearing that they might be occupied by Union troops, relocated further inland and Urbanna became a Confederate Army base with artillery batteries placed above the town along Orange Creek and to the south near the tiny settlement of Sandy Bottom which is now the still very small hamlet of Deltaville. Besides the former courthouse that dated back to1745 and was a Confederate barracks during the War, Urbanna itself had only one store, one church and a schoolhouse. Besides occasional raids by Union troops from Fort Monroe and the shelling of the courthouse in late 1861 by the Union revenue cutter “USS Harriet Lane” with her three thirty-two pound cannons and four twenty-four pond howitzers, none of which did any serious damage, the town remained in Confederate hands throughout the War. The “Harriet Lane” had been used earlier that year in the failed attempt to reinforce Fort Sumter in Charleston, as well as engaging in a battle that June with a Confederate battery on Pig Point below Hampton and was captured at Galveston, Texas, in 1863.

Middlesex County was also the scene of some minor naval actions in 1863 and a number of guerilla raids on Union troops by irregular Confederate cavalry units attached to Colonel Thomas Rasser’s Fifth Virginia Cavalry, such as those led by Captains John Yates Beall and Thaddeus Fitzhugh who carried out operations from their base in nearby Matthews County. In some of these actions, the cavalry acted in cooperation with Lieutenant John Taylor Wood of the Confederate Navy. Wood, the grandson of President Zachary Taylor and the nephew of President Jefferson Davis, would later hold the unique position of being both a captain in the Confederate Navy and a colonel in the Confederate Army, as well as an aide to President Davis. Lieutenant Wood had also served aboard the first Confederate ironclad, the “CSS Virginia,” in its battle the previous March in Hampton Roads with the Union’s “USS Monitor.” In that engagement, a tactical victory for the Confederacy, Wood manned the gun that seriously wounded Captain John Worden, the commander of the “Monitor.”

The engagements in Middlesex County in which the cavalry acted with Wood took place in August of the following year with the capture of two Union gunboats, the “USS Satellite” and the “USS Reliance” on the Rappahannock River below Urbanna near Stingray Point at the end of the peninsula. Wood left Richmond for Middlesex County on August 12 with eighty-two hand-picked men from the James River Squadron and four large open boats called boarding cutters mounted on modified wagons. Four days later they arrived at Turk’s Ford on the Piankatank River west of Urbanna and made camp but learned that the Union gunboat “USS General Putnam” had been warned of their arrival. Skirmish lines were formed along both shores and when Wood’s men fired on the gunboat, killing its commander, William Hotchkiss, and wounding several of its crew, the ship quickly retreated back down the river. The expedition then moved overland to the Rappahannock River below Urbanna and headed for Stingray Point where they boarded and captured the two Union gunboats with a loss of four Union dead and thirteen wounded, with Wood having only three men wounded. Wood later used the two gunboats to capture three commercial schooners in Chesapeake Bay and then sailed the ships up the Rappahannock River to Port Royal. A full-size replica of one of Wood’s cutters mounted on a wagon is now on display at the Maritime Museum in the present-day hamlet of Deltaville.

The second major action in the county took place in May of the following year when the Thirty-Sixth U. S. Colored Infantry Regiment landed at Mill Creek near Sandy Bottom, burned the mill there, ransacked the lighthouse on Stingray Point, exploded a supply of Confederate ammunition and then returned to Stingray Point to be transported back to Fort Monroe. On the way, they encountered a small contingent of Confederate cavalry and Marines and in the ensuing skirmish one Union soldier was killed and three were wounded. The Confederates lost four dead and three captured. The greatest contribution made by the county to the war effort though were the several hundred men it supplied to the Confederate military, with most of them serving in the Fifty-Fifth Virginia Infantry Regiment which was engaged in almost every major battle in the east, including the Seven Day’s Battles, Second Manassas, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, Gettysburg, and the siege of Petersburg. There are also many vignettes about local people during the War which appear in “Soldiers At The Doorstep : Civil War Lore,” one of the many books about Middlesex County written by Larry Chowning, a reporter for the Urbanna Southside Sentinel. One tale concerns Colonel William S. Christian of the Fifty-Fifth Virginia Infantry Regiment who had just returned to his family home near Urbanna for a wartime visit when he was seen by a Union cavalry patrol. The patrol recognized his rank and fearing that he might be leading his regiment, rode on to Urbanna. A larger group returned later to search for the Confederate officer and when they found only his sister Mattie at home, they demanded to know the whereabouts of her brother. One of the Union soldiers held a pistol to the young girl’s head and threatened to shoot if she did not tell them, but Mattie, who was normally even afraid of thunderstorms or a mouse, defied them and was reported to have bravely said, “You coward, if I had ten thousand heads, you might blow them all off before I will tell where my brother is.” No shot was fired and the Union hunters rode off without their quarry. Christian was later captured at Gettysburg but survived the War, became a medical doctor and was the superintendent of Middlesex County’s public schools before his death in 1910.

While the soldiers referred to in Chowning’s title were Union troops, not all those that came knocking on the county’s doors wore blue uniforms. On April 16, 1862, the Confederate government enacted the Conscription Act, America’s first military draft, which called for all able-bodied white males between the ages of eighteen and thirty-five to be liable for three years of military service. As the the need for more recruits progressed, subsequent acts eventually extended the age limit to those between seventeen and fifty. Another of Chowning’s accounts tells a story about the ancestor of one of our dearest friends who was born in what was once Sandy Bottom and now lives in Williamsburg. Her great, great grandfather, Alonzo Harrow, was a teenager in the spring of 1862 and when his mother Almedia heard that Confederate conscription officers were heading towards the area, she vowed they would not take her son. Chowning was told two slightly different stories about how Alonzo eluded being found, with the first stating that his mother hid him between the bed ropes and a feather mattress and then covered the bed over with some clothing to avoid detection, while the second account had him hiding behind the bed’s headboard. In the latter version, Mrs. Harrow put Alonzo’s three younger brothers, Buck, Hervey and Johnny, on the bed behind which Alonzo was crouching and when the officers asked where her sons were, she truthfully said they were in bed. After seeing that the three boys on the bed were too young, the conscripters left and went to other houses on Lover’s Lane. Whichever of the accounts in correct, Alonzo never went to war and lived out the rest of his life farming and fishing in Sandy Bottom, which became Deltaville in 1909, until his death there in 1933 at age eighty-seven. Another resident on Lover’s Lans was not so fortunate, however, for in that home the conscription officers found Alonzo’s cousin, twenty-seven year old William Henry Norton, with his wife Evalina and their two small sons, Hervie and John. Norton was drafted into the Army and served with the Twenty-seventh Virginia Cavalry until he was killed two years later during the Second Battle of Cold Harbor.

As a footnote to the unpopular Confederate draft legislation which many Southerners attempted to avoid . . . in 1863, the Union followed suit with a similar conscription law, but this one was met with not only evasion but violent resistance in many cities throughout the North, most notably being the bloody July draft riots in New York City which claimed up to a hundred twenty lives and at least two thousand people injured. Up until 1863, the public generally believed the government’s claim that the War was merely a necessary campaign to preserve the union by suppressing a rebellion but following Lincoln’s 1862 Emancipation Proclamation, public sentiment regarding the War’s raison d’être began to metamorphosize into what many now angrily thought was a crusade to free the slaves . . . the mantra that still continues to this day. In the New York draft riots, much of the rage was directed at the city’s black residents who were now thought to be the cause of the War and almost half of those killed were Blacks, with many being beaten or burned to death and some lynched from trees and lamp posts. A large number of buildings throughout the city were also burned to the ground, including many in the black neighborhoods, as well as a black orphanage on the corner of Fifth Avenue and 44th Street in mid-Manhattan. As the New York police and State Militia could not quell the mayhem, General Grant was forced to send in twelve Union Army regiments, some of which had just fought at Gettysburg, to finally restore order.