Post Civil War racial adjustment was a problem Southerner whites didn’t want to face and Northerner whites declined to share.

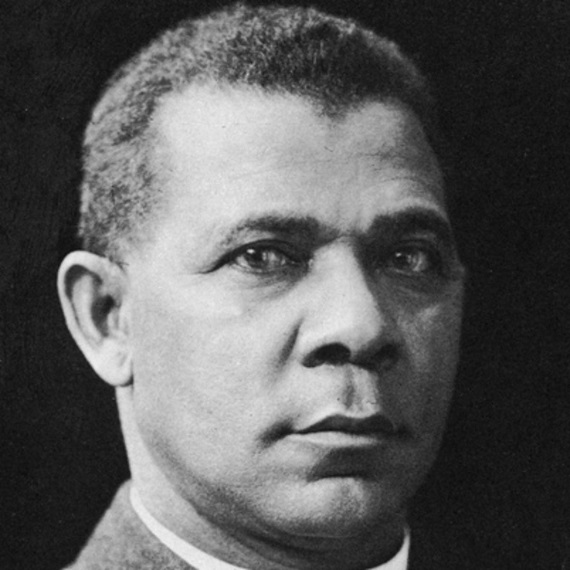

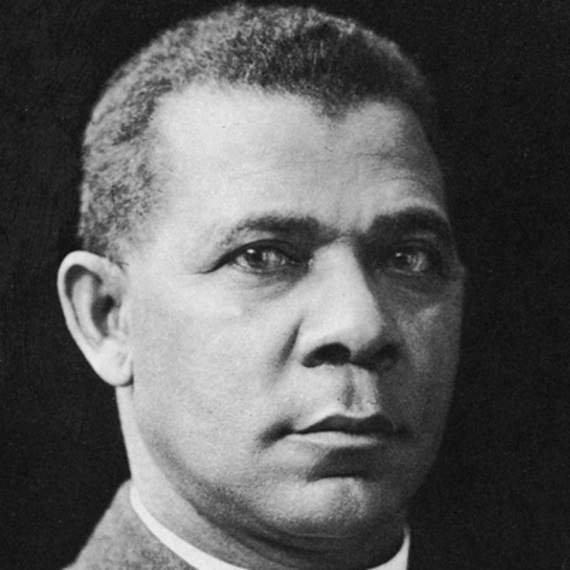

When the war started 40% of the Confederacy’s population was black whereas it was only 1% in the free Northern states. Even a century later blacks represented only 2% of the population of Massachusetts, which was the birthplace of abolitionism. Unfortunately, Reconstruction era black voters in the South were manipulated to provide a reliable voting block in order to sustain the Republican Party’s control of the federal government. Once the block was no longer needed the Party abruptly dropped the constituency. Thereafter, Southern blacks were on their own. One of their earliest leaders, Booker T. Washington, rose to prominence about fifteen years later in the early 1890s.

Four years after the collapse of the last Carpetbag regimes, Alabama allocated $2,000 to form the Tuskegee Institute as a college for black teachers in 1881. Twenty-five year old Washington, who was a former slave, became the school’s principal. He had learned his trade at Virginia’s Hampton Institute, which loaned him enough money to buy 100 acres of land for Tuskegee. Seven years later the 540-acre school had over 400 students. They were trained in skills such as carpentry, cabinetmaking, printing, and shoemaking. Girls learned how to cook and sew while boys were taught farming and dairying.

Teachers and students provided a large part of the institute’s needs thorough their own labor. They produced and sold bricks, lumber, furniture, wagons, tools, and clothing. To those who felt that such labor was beneath their dignity Washington answered, “No race can prosper till it learns that there is as much dignity in tilling a field as in writing a poem.” He also worked in the fields alongside his critics.

Finally at age thirty-nine in 1895 he was invited to speak to an audience of black and white Southerners in Atlanta. The occasion was the Cotton States International Exposition, which was a Southern version of Chicago’s Columbian Exposition three years earlier that celebrated the 400th anniversary of America’s discovery. Since the Atlanta exposition was partly funded by a congressional appropriation the convention managers wanted to show that the South was not as racially blighted as some Northerners presumed.

Although Washington was the opening day’s last speaker, the auditorium’s segregated audience was packed. He was received politely. When he explained that he encouraged his students to avoid politics and concentrate on becoming productive artisans, the audience became increasingly attentive.

He conceded the reality of persistent racial tension, but chose not to blame whites for their part. Instead he admitted black errors, “Ignorant and inexperienced, it is not strange that in the first years [of freedom]…a seat in Congress or the legislature was more sought [by freedmen] than real estate and industrial skills.” The entire South had suffered from such mistakes. As a result, some Southern blacks advocated emigration and others argued that Northerners should provide financial aid. Although possibly well intentioned, Washington rejected such solutions. He explained with a parable.

When a ship that had exhausted its potable water after being lost at sea first saw the masts of a potential rescuer, the crew hoisted signal flags asking for water. The second ship replied, “Cast down your bucket where you are.” Thinking they had been misunderstood the imperiled crew replied, “We die of thirst!” The presumed rescue ship repeated, “Cast down your bucket where you are.”

When the thirsty crew finally complied and threw a rope-connected canvas bucket overboard they discovered that it contained fresh water when pulled on deck. Even though they were beyond the sight of land both ships were off the coast of the mighty Amazon River, which flushed fresh water far out to sea. Washington concluded:

To those of my race who depend upon bettering their condition in a foreign land, or who underestimate the importance of cultivating friendly relations with the Southern white man, I would say: “Cast down your bucket where you are!”—cast it down in making friends in every manly way of the people of all races by whom we are surrounded.

He went on to give the same advice to white Southerners who wanted to immigrate foreigner workers, “Cast down your bucket among …[us]…who have tilled your fields, cleared your forests…[and built]…your railroads and cities….In the future…we shall stand by you with a devotion that no foreigner can match…interlacing our industrial, commercial, civil, and religious life with yours.

Washington went on to boldly address social segregation. He raised his right arm high into the air with the fingers initially outstretched before closing them into a first. “In all things that are purely social, we can be as separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress.” Conceding disappointment among blacks with their lower social status enforced by segregation he nevertheless added, “The opportunity to earn a dollar in a factory just now is worth infinitely more than the opportunity to spend a dollar in the opera house.”

The speech was received enthusiastically. Presumably whites liked the conciliatory message whereas black reaction was amplified by the favorable white reaction and the simple fact that a black man was on the stage.

Washington remained a leading spokesman for the African-American community for the rest of his life. In 1901, President Theodore Roosevelt invited him to be the first black to join an official White House dinner. He still headed-up the Tuskegee Institute when he died in 1915.