Lewis Burwell Puller is a Marine Corps legend and American hero. Nicknamed “Chesty” for his burly physique, he was one of the most combat-hardened leaders in military history and saw action in Haiti, Nicaragua, WWII, and Korea. The winner of five Navy Crosses and many other medals, he will always be remembered as a fierce warrior and proud patriot.

One area of Chesty’s life that deserves more scholarly research is his southern heritage. He was born in Virginia in 1898 and was raised on stories of the Confederacy. His grandfather, John Puller, was killed while riding under Jeb Stuart at the battle of Kellys Ford in 1863. Local veterans told young Chesty about his grandfather’s bravery, as John had stayed atop his saddle long after having his midsection torn apart by a cannon. After his grandfather’s death, federals burned the Puller home and his grandmother was forced to walk ten miles, through a sleet storm, for help.

Puller was proud of his ancestry, and his southern roots ran much deeper than The War Between the States (his term of choice for the “Civil War”). His family had come to Virginia in the early 1600s and he could trace back relatives to the colony’s House of Burgesses. Chesty noted that he was also a relative of Patrick Henry, George S. Patton, and that he had a great-uncle named Robert Williams, who deserted the south to join the federal army (the Virginia portion of the family stopped speaking to Williams after this, and he later went on to marry the widow of Stephen A. Douglass). Another famous cousin of Puller’s, named Page McCarthy, was a Confederate captain that fought the last legal duel in Virginia and killed his opponent.

The Confederacy and its legacy left a lasting impression on a young Chesty. As a boy, he witnessed Robert E. Lee Jr. bring a buggy by his home weekly to sell eggs and vegetables to support the Lee family. Puller’s favorite Confederate was Willis Eastwood, who rode with his grandfather and became mayor of West Point. In addition, the Puller home was filled with pictures of great Confederates like Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson.

As a southerner, Chesty also learned the importance of land and self sufficiency. After his father’s death in 1908, Chesty began trapping to support his family. He would capture muskrats, sell the hides for fifteen cents each and then sell the carcasses to poorer families for five cents. He also would catch local crabs and sell them for twenty five cents a dozen. By the age of twelve, young Puller had killed his first turkey and also learned how to hunt rabbits. After his military fighting career was over many years later, Chesty noted that he learned more about the art of war by hunting and trapping, than he learned from any school. He insisted that the skills he learned as a kid, living off the land, saved his life many times in combat.

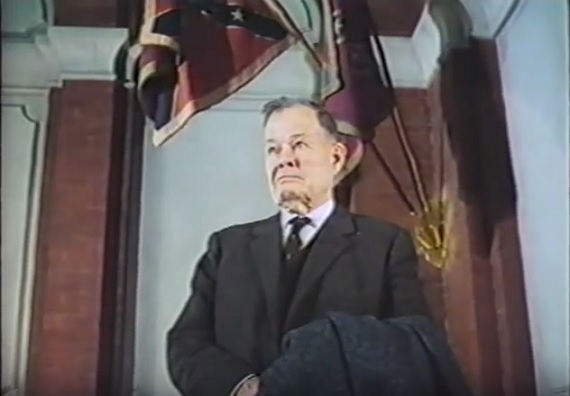

Puller had spent his entire childhood admiring the military leaders of the south. In particular, he loved Stonewall Jackson and he admired the large statue of Jackson that stood at VMI, where Jackson was formerly a professor. One of Puller’s most prized possessions was a copy of George Henderson’s biography of Stonewall Jackson, which Chesty had read repeatedly. He underlined most of the text, wrote Jackson’s famous quote “Never take counsel of your fears.” The book also contained notes on the casualties of Chesty’s men at Guadalcanal and his medals. It was referred to so frequently that it was embedded with dirt and held together with bicycle tape. In many ways, Lewis Puller and Stonewall lived parallel lives. They were both proud Virginians that scored low on VMI’s marks, yet were unmatched in the leadership on the battlefield. Chesty also frequently visited the tomb of Robert E. Lee at Washington and Lee University campus. A documentary, directed by John Ford and narrated by John Wayne, titled “Chesty: A Tribute to a Legend” features scenes of an elderly Chesty visiting the tomb of Lee.

In the tradition of many other famous southerners, Chesty also had an appreciation for the classics. At a young age, he picked up a copy of Caesar’s Gallic Wars and even translated it from Latin. All of these experiences (living off the land, being raised on stories of the south, an interest in military leadership early on) would help mold Chesty into an ideal soldier.

Chesty exemplified the southern military tradition by having an unsurpassed sense of duty to his country, and by being a fierce warrior. The military excellence of the south can be traced back to before the American Revolution. George Washington and Francis Marion, for example, both gained their initial combat experience in the French and Indian War. It could be argued that Chesty was a more efficient leader than both of these men. Contrary to popular myth, Washington was not a great tactician or leader and his victory at Yorktown can really be attributed to the French. One of Washington’s most memorable moments is enduring hardship at Valley Forge, which Chesty Puller compared to his experience in Korea by saying:

“Our forefathers at Valley Forge have been mentioned here tonight as the often are. Well, I can tell you that Valley Forge was something like a picnic compared to what your young Americans went through at the Chosin Reservoir, and they came out of it fine. It never was anything like twenty-five below zero at Valley Forge, either.”

Francis Marion, known as the “Swamp Fox,” used guerilla tactics and partisan warfare to fight the British in South Carolina. This type of fighting drove the British out of the Carolinas and into Virginia, where they eventually surrendered. This method of warfare today is referred to as “maneuver warfare” and has been officially adopted as the Marine Corps doctrine. Marine Corps tactics and the history of southern warfare go hand-in-hand; even today, Parris Island, South Carolina is the main training center for the Marines on the east coast and graduates at least 17,000 men and women per year.

The concept of maneuver warfare is defined by the Corps as “warfighting philosophy that seeks to shatter the enemy’s cohesion through a variety of rapid, focused, and unexpected actions which create a turbulent and rapidly deteriorating situation with which the enemy cannot cope.” This was exactly how Chesty was operating in Nicaragua, Haiti, Korea, and the Pacific.

Southern men like Francis Marion and Nathan Bedford Forrest also implemented these ideas of hitting the enemy hard and fast, with accurate firepower. All of the great southern military leaders, from Washington and Marion, to Lee, Jackson, and Forrest, and then finally to Chesty, were also beloved by their men. Washington got his men through Valley Forge by making sure they had a cup of rum each day and making himself visible to the troops. Francis Marion’s men were unpaid and soldiered on their own accord. Forrest will always be remembered for his battle philosophy of being “first with the most.” Lee and Jackson were men of unshakeable faith and inspirational leadership.

Chesty is still frequently quoted in the Marine Corps, with men carrying on his quotes like “We’re surrounded? Good, now we can fire at those bastards from every direction.” On another occasion, when testing a flamethrower, Puller asked “Where the hell do you put the bayonet?” so that he could stab the enemy after burning them. Puller will always be remembered for his courage and actual presence among his men. Many leaders from Puller’s day were promoted on the basis of their letter-writing ability, and literally gave orders from station wagons, far from the front lines. Chesty, on the other hand, appealed to his men’s senses and spiked morale by his presence. He made sure his men had good chow, shelter, and preferred taking care of matters hands on.

After the Korean War, Chesty’s popularity soared. This presence, combined with his straightforward honesty, soon made him many enemies in Washington. In his early military days, Chesty was chasing bandits and collecting tributes from other countries. By the Vietnam era, Marines were being used to pay tributes to other countries. Chesty was not afraid to call it like he saw it and comment on the misuse of the military. He was a proud believer in esprit de corps, which is love for one’s military machine above all else. Puller did not believe in using the military to give money to countries, especially in the case of billions we will probably never be paid back. He firmly related this belief to his understanding of southern history in a never-before transcribed 1959 speech where he stated:

“I can remember when our great president, Andrew Jackson, sent a navy ship to Italy and gave its captain orders to fire a few shots over the city, send a detail ashore, and collect what they owe us. He fired a few shots over the town, he didn’t have to send the Marines ashore to go and get it. By God, they brought the money out.”

Puller also commented that the military was fighting to sustain war in Vietnam, not to win. He also openly criticized the devaluation of the American dollar, the move away from the gold standard, and inflation. All of these topics were discussed in his 1959 speech, where Chesty openly lamented the upward-spiraling cost of living, combined with the devaluation of the dollar–things which he argued were causing the production of counterfeit currency. He stated that the military was also increasing its expenditures on unnecessary things like private baths for each soldier. Even with all of his dissatisfaction, he always kept his home open to Marines and continued to volunteer for service into his 60s.

Devastation struck Chesty’s family after his only son, Lewis B. Puller Jr., lost both legs and parts of his hands in Vietnam. This occurred after years of Chesty’s critical comments of United States policy, and resulted in Chesty’s desire to offer his own ideas to make the country stronger. One solution Chesty suggested to improve the United States world-wide presence was to give less money to scientists, and put money towards putting young men in schools around the world. This would integrate young Americans into other cultures, help them truly learn languages, and give the United States an advantage in trade and communications.

When we examine Chesty through the lens of his southern heritage, his life and actions begin to make a lot more sense. His combat skills were second to none and reminiscent of men like Francis Marion, Stonewall, and Nathan Bedford Forrest. His devotion to liberty are reminiscent to men like Washington and Lee. Also like a true southerner, Chesty believed in limited government and low taxation. Puller may not have been the best public speaker or man of letters. But he was and will always be a true son of the south. His own history deserves just as much examination as his military leadership.