As noted in earlier posts, the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) and many academic historians are promoting a false narrative that the Confederate statues erected between 1900 and 1920 were celebrations of white supremacy. In reality, the statues were built because the old veterans were dying-off, which is why there was also a simultaneous surge in Civil War memorial-building in the North.

Nonetheless, academics are on a mission to “prove” their point by finding examples of statue inscriptions or dedication speeches that celebrate the Anglo-Saxon race or affirm white supremacy. Yet Anglo-Saxon pride and white privilege was common throughout all of America during that era. Consider, for example, the widespread obsession with defeating black heavyweight boxing champion Jack Johnson.

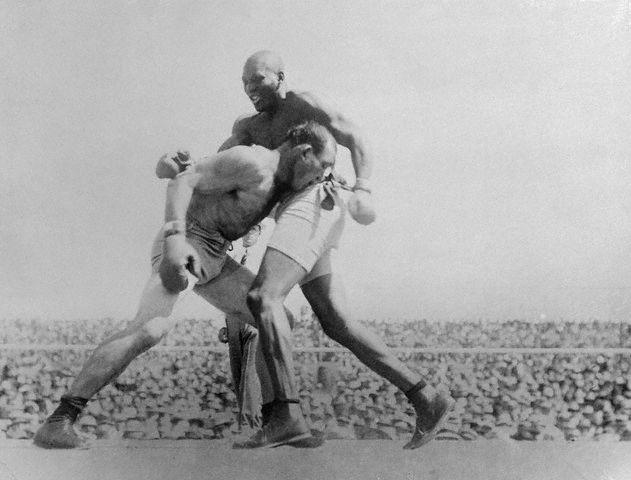

Johnson became the first black to hold the title in 1908 by beating the reigning white champion, Tommy Burns. Most white boxing fans were outraged that a black had become champion. As a result, promoters searched for a “Great White Hope” to beat Johnson. In 1910 they matched him against previous champion Jim Jeffries, who had earlier retired undefeated.

The bout attracted unprecedented attention. Led by The New York Times, the mainstream press promoted hostility toward African-Americans: “If the black man wins, thousands and thousands of his ignorant brothers will misinterpret his victory as justifying claims to much more than mere physical equality with their white neighbors.” After Johnson won the fight, race riots erupted in fifty cities within twenty-five states. Examples include New York, Washington, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, Omaha, Wilmington, Columbus, St. Louis and Pueblo, Colorado as well as the Southern towns of New Orleans, Little Rock, Atlanta and Houston.

It took boxing promoters another five years to find a six-foot-seven-inch white fighter, Jess Willard, to beat the aging Johnson in 1915. After winning the Havana bout, Willard temporarily became the most celebrated American. When his victory was displayed on a bulletin board in New York’s financial district the roar from the streets “would have done credit to a Presidential victory,” according to the New York Tribune. “For a moment the air was filled with hats and newspapers. Respectable businessmen pounded their unknown neighbors on the back” and acted like gleeful children. At a time when the average American earned $600 a year, a New York lecture hall offered Willard $5,000 for a single week’s engagement.

After some blacks started to migrate to Northern states early in the twentieth century race riots began to erupt in their new hometowns. A black who swam offshore at a Chicago “whites only” beach triggered a riot that left thirty-eight people dead in 1919. President Woodrow Wilson put most of the blame on the whites. About one thousand blacks lost their homes to arson. Wilson also mostly blamed whites for 1919 rioting in Washington, D. C. that caused about forty deaths and one-hundred-fifty injuries.

Two years earlier East St. Louis whites launched wholesale attacks against blacks after five-hundred were hired to replace whites during a worker strike. Claiming that “Southern negroes deserve[d] a genuine lynching” whites hanged several blacks. Estimates of African-American deaths ranged from 40 to 200. About 6,000 abandoned the city.

Even though blacks represented just 5% of the people in Springfield, Illinois a 1908 race riot left sixteen people dead and hundreds of homeless blacks in its wake. Conflicts between blacks and Irish-Americans led to a New York City riot in 1900 that required hundreds of police to intervene.

Since racism permeated the entire country from 1900 to 1920, it’s a stretch requiring a bungee cord to conclude that racism was a significant reason to erect Confederate memorials. The obvious explanation is that the old soldiers were fading away and the impoverished South had finally accumulated enough money to memorialize them some fifty years after the War had ended.