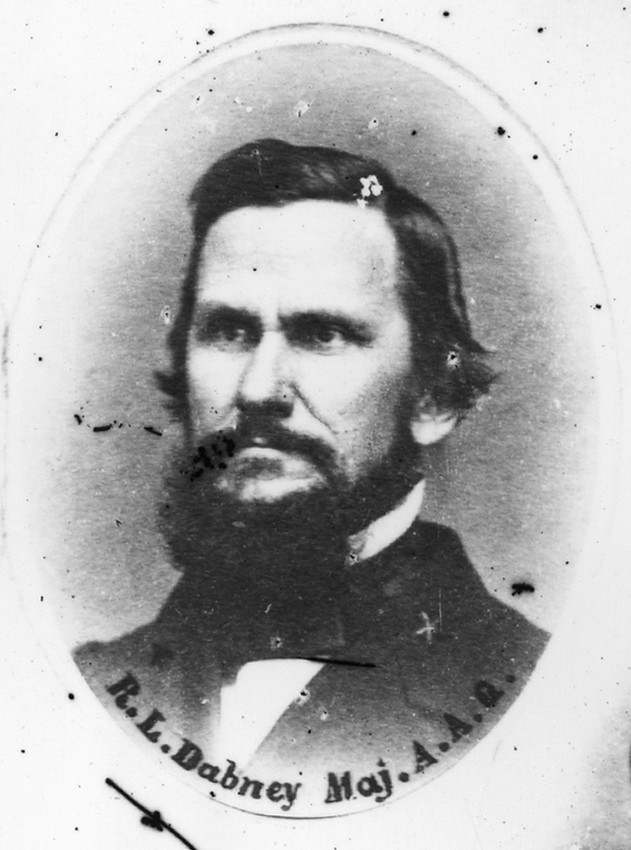

Robert Lewis Dabney (1820–1898) defended the South both during and after the War Between the States. During the war, this professor of theology left his work at Union Theological Seminary to serve as chaplain for the Confederacy in 1861 and then as chief of staff to General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson in 1862.

After the war, Dabney made it one of his chief tasks to defend the South politically and morally through his writings. He memorialized one of the greatest men produced by the Old South in his biography of Stonewall Jackson. Dabney’s wife and Jackson’s wife were cousins, and following the death of the great general on May 10, 1863, Mrs. Jackson asked Dabney to write a biography of her late husband. Dabney finished the work in 1866, entitled Life and Campaigns of Lieut. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson.

Dabney also sought to defend the South’s former practices against the criticisms of the Northern abolitionists. In 1867, he published A Defence of Virginia (and Through Her, of the South), in which he condemned the slave trade but argued the Bible permits the practice of slavery. Dabney spent the rest of his days fending off the wave of progressivism that invaded the South after the Union army. He wrote essays for journals after the war, many of which were collected and published at the end of his life in the four-volume Discussions, edited by his friend C.R. Vaughan. Dabney wrote on a wide array of topics, but his three greatest targets were industrialization, public education, and egalitarianism.

Dabney on the New South

One of Dabney’s most insightful speeches was his 1882 address “The New South” at Hampden-Sydney College, in which this defender of the Old South warned the younger generations of the changes taking place in his homeland. (This speech is recorded in the fourth volume of the Discussions.) As usual, Dabney came out swinging, asserting that the changing conditions in society were “not because the old forms were not good enough for this day, but because they were too good for it.”

The first of these changing conditions was the new “theory of human rights” (elsewhere he referred to this as an “anti-biblical theory of rights”). Dabney defended the British view of equality that every citizen “was equal before the law,” a tradition Americans had inherited. This “equality of the golden rule” was now being replaced by the Jacobin view that “absurdly claims for every human the same specific powers and rights.” Dabney condemned the modern liberty of “absolute license” in contrast to the former liberty “to do those things and those only to which God’s law and Providence gave him a moral right.”

Next he turned his attention to the growth of big cities—“When our former constitution was adopted, America contained no metropolis, not even any city of note.” Dabney asserted that the financial growth of cities like New York would bring “political subjection.” He also raised concern over new technology, which pushed manufacturing out of the home and into factories, centralizing production so that the former “free-holding citizen is sunk into the multitudinous hireling proletariat.”

The rise of big cities and improved technology culminated in the new industrial way of life, Dabney’s chief concern in this address. Agricultural and homeward activities, former staples of Southern life, were being traded for factory life. Further, Dabney claimed this industrialization was resulting in “extreme inequalities of fortune, expenditures and luxury which now deform American society.” He predicted that political corruption would result—“This enormous inequality in wealth will seek to protect, to assert itself in politics.”

Dabney explained that the coming universal suffrage “leaves the rich man no legitimate form for the assertion of his superior weight or the protection of his superior interests in the State. Wealth, then, must seek for itself illegitimate forms. And in obeying the inevitable impulse through these illegal ways, it must corrupt itself, and the institutions of the land.”

While the press had been looked to as the “safe guardian of popular institutions,” Dabney thought they too had been corrupted by money. The press “are either the tools of parties and used for exclusive partisan purposes” or are “mere joint-stock concerns for money making.” The result of both is that “contents of the journal are not dictated at all by truth or right, but solely by self-interest.”

Finally, Dabney focused on the change brought by the “extension of suffrage.” He asserted that broader voting rights would result in political class warfare—“The attempt of the proletariat and their demagogues to use their irresponsible suffrage for plunder; the resistance of the capital-holding minority to this plunder.” This has played out in America with the “plunder” of heavy taxation and government redistribution and the “resistance” of cronyism and special legislation.

All of these changes would corrupt American politics—“The result is, that self-defense invents illegitimate modes, and the unrighteous assault on property is met by the illegal use of property to protect itself and to inflate itself until the moral corruptions wrought in our politics fester to putrescence and dissolve the body.” He continued, “Under a thin veil of radical democracy, the government has already become an oligarchy . . . It is Washington or Wall Street which really dictates what platforms shall be set forth, and what candidates elected and what appointments made, not the people of the States.”

A Final Word

Dabney’s “New South” address is a fascinating analysis of postbellum change by one of the great intellects of the Old South, as he warned of the dangerous outcomes of industrialization, universal suffrage, material prosperity, and the growth of big cities. However, Dabney did not close his address with criticism, but prayed and hoped for the best—“Our best prayer for you is, that out of the present foul transition, a good Providence may cause some new order to arise tolerable for honest men. The changes implied in the introduction to this new order . . . must be accepted by me as inevitable. But the principles of truth and righteousness are as eternal as their divine legislator.”

Dabney charged his hearers to follow the Bible and seek truth and righteousness, not the idol of riches that was a temptation for the New South. As he exhorted, “Here, in one word, is the safe pole-star for the ‘New South’; let them adopt the scriptural politics, assured that they will ever be as true and just under any new regime as under the one that has passed away.”

Portions of this essay are adapted from the introduction to Dabney on Fire: A Theology of Parenting, Education, Feminism, and Government.