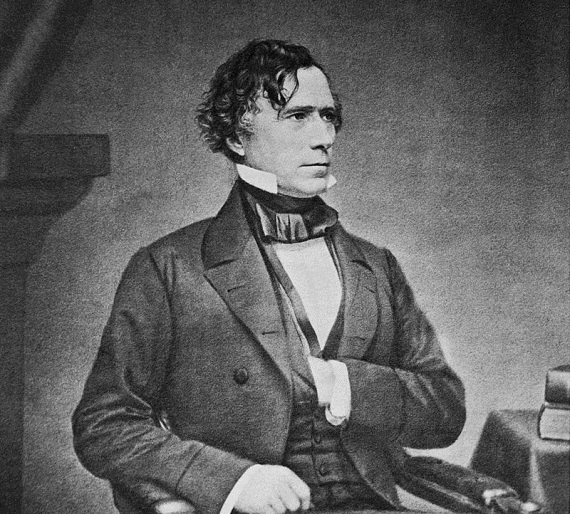

On the stump in New Boston, New Hampshire in early January 1852, Franklin Pierce gave a long oration during which free-soil hecklers forced him to address his ideas on slavery. “He was not in favor of it,” the Concord Independent Democrat reported. “He had never seen a slave without being sick at heart. Slavery was contrary to the Constitution in some respects, and a blot upon the nation.” Pierce also scorned the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act, which trumped various state-level “personal liberty laws” that weakened the original 1793 fugitive slave law. “[H]e said he did not like the law—he loathed it—it was opposed to humanity, and moral right.” Despite all this, the Constitution was a compromise, and if it had not been for the slavery provisions it would not have been enacted at all. He may not like slavery or the fugitive slave laws, but the Constitution recognized them, and the benefits of the Constitution far out-weighed any other issue or concern. Disliking slavery yet fearful for national survival outside the Constitution—this was Pierce’s great dilemma and it makes a useful starting point to reassess his ideas, and those of conservative Northern Democrats, on the limits of abolition and protest.[1]

Franklin Pierce had no interest in holding slaves, nor did he speak philosophically about slavery as a “positive good.” As early as 1838, he went on record saying slavery was “a social and political evil” that was also, like it or not, protected by the Constitution.[2] Instead, he had a series of practical concerns over abolitionism. His opposition to abolitionism was not evidence of “racial hypocrisy,” in Daniel Feller’s useful formulation—where antebellum politicians opposed slavery, yet “constantly attuned their political position to practical considerations of context and consequence”—but something more fundamental: a suspicion of abolitionist civil disobedience and “agitation” as futile, dangerous, driven by philanthropic abstractions rather than history and law, and anti-democratic. These suspicions reflected a tension within the antebellum Democratic Party in relation to slavery—how can we reconcile an advocacy of democratic decision-making with the existence of transcendent moral values, the Constitution with the Bible?[3]

For Pierce, abolitionist protest was futile because it would spur an angry Southern counter-reaction and invigorate pro-slavery forces, not weaken them. “Interference on the one hand to procure the abolition or prohibition or slave labor in the Territory has produced mischievous interference on the other for its maintenance or introduction,” Pierce explained in his January 1856 Kansas Proclamation. “One wrong begets another. Statements entirely unfounded, or grossly exaggerated, concerning events within the Territory are sedulously diffused through remote States to feed the flame of sectional animosity there, and the agitators there exert themselves indefatigably in return to encourage and stimulate strife within the Territory.” In his view, extra-political activity spun out of control, both sides dug in to resist it, and violence resulted.[4] Civil disobedience solved no problems, but instead led to a host of unintended consequences. It only aggravated existing tensions and created further bitterness.

Pierce used similar language in his biting December 1856 Fourth Annual Address: “Extremes beget extremes. Violent attack from the North finds its inevitable consequence in the growth of a spirit of angry defiance at the South.”[5] Northern Democrats often utilized this understanding. Pierce’s successor James Buchanan said virtually the same thing describing the “gag rule” crisis of the 1830s and 1840s in his post-war memoir. “It is easy to imagine,” Buchanan wrote, “the effect of this agitation upon the proud, sensitive, and excitable people of the South. One extreme naturally begets another. Among the latter there sprung up a party as fanatical in advocating slavery as were the abolitionists of the North in denouncing it.”[6] Not only did abolition fail to disturb slavery, it strengthened it and ignited a dirty frontier war in Kansas.

This futile plan of civil disobedience was also destructive; it threatened the Union that made American liberty, and the Constitution which protected it, possible. Abolitionist agitation exhibited civic intolerance for the institutions and ways of life of other communities. This refusal to “cultivate a fraternal and affectionate spirit, language, and conduct in regard to other States and in relation to the varied interests, institutions, and habits of sentiment and opinion which may respectively characterize them,” corroded the glue of the Union, Pierce asserted; without it the United States “could not long survive.”[7] Civil disobedience signaled disrespect for the choices of fellow citizens in other States, the inevitable result of which was violence, disunion, and war. Being such a large and diverse nation, diversity of habits and ideas was inevitable. “[I]t was vain to expect the prevalence of the same sentiments or concurrence of the same opinions,” Pierce told ex-president John Tyler and a welcoming committee at White Sulpher Springs, Virginia in 1855. “But this was true during the Revolution. Just as true at the time of the adoption of the Constitution, which embraced the then thirteen States as it is now.”[8] Why was it different now? Pierce warned in his 1855 Annual Address: “If one State ceases to respect the rights of another and obtrusively intermeddles with its local interests; if a portion of the States assume to impose their institutions on the others or refuse to fulfill their obligations to them, we are no longer united, friendly States, but distracted, hostile ones, with little capacity left of common advantage, but abundant means of reciprocal injury and mischief.” Imagine if the same type of “intermeddling” occurred among sovereign states, he continued. The result would be war. Such a terrible result was delayed in this case because abolition’s tactics were “perpetuated under the cover of Union.”[9] In 1863, in the midst of the War and reflecting back, he continued to blame “the vicious intermeddling of too many of the citizens of the Northern states” for the conflict, who by their intrusions played into the hands of fire-eating, secessionist “discontents.”[10]

Had the sectional spirit prevailed in the 1770s and 1780s, there would have been no Union or Constitution. Pierce declared in 1855:

An opposite spirit—one sectional and fanatical—would have stamped disgrace and defeat upon the ensign of the revolution. It would have paralyzed the energies, which, in that great contest for the right of self-government, inspired words of defiance, and gave blows of vigor when vigor was needed. It would have made this glorious Constitution—under which we have lived together and grown together in peace, under the controlling influence of which we have enjoyed for more than sixty years such a degree of advancement, prosperity, and happiness, individually and socially, as States and as a Confederacy, as the world has ever witnessed, and which only mad fanaticism would recklessly destroy—an impossibility.[11]

Mindful of the uniqueness of American democracy in the world, he claimed that the great duty of American politicians was “to preserve that which if once lost can never be recovered.”[12]

If the Constitution failed and collapsed in a civil war, what would succeed it?—a banana republic of constant revolutions and turmoil, a return to colonial status in a foreign empire, or perhaps a European-style autocracy? America would cease setting an example to aspiring republicans in Europe and South America. “My hope and faith in the Constitution and in the permanence of the institutions which it upholds is strong, but with a knowledge of the weakness of poor human nature, and with the light of history cast upon our path, I certainly need not warn you that the loss of the great blessing which you now enjoy is not impossible,” he told a New Hampshire audience in October, 1856. Sounding more like John Winthrop’s 1630 Model of Christian Charity (“For we must consider that we shall be as a city upon a hill. The eyes of all people are upon us …”) than an antebellum politician, Pierce warned his fellow New Englanders, “Never allow your minds to be diverted from the fact that this is the great experiment in modern times, of man’s capacity for self-government, and that if the experiment cannot succeed under this Constitution and this union of the American States, its success on this continent under any new arrangement is hopeless.” Only a renewed fealty to the Constitution can save the Union and American liberty “from those calamities of civil war and of political anarchy or tyranny which destroyed the ancient Republics, and which now prevail in those of South America.” Slavery agitation and civil disobedience threatened those unique yet fragile American liberties. Once gone, they may never return.[13]

In addition, if states were denied admission to the Union because of their stance on slavery, would not that “of necessity drive out the oppressed and aggrieved minority and place in presence of each other two irreconcilably hostile confederations?”[14] When he depicted a future of secession, the creation of rival sectional governments, and war, Pierce’s language darkened:

[For abolitionists] and the States of which they are citizens the only path to its accomplishment is through burning cities, and ravaged fields, and slaughtered populations, and all there is most terrible in foreign complicated with civil and servile war; and that the first step in the attempt is the forcible disruption of a country embracing in its broad bosom a degree of liberty and an amount of individual and public prosperity to which there is no parallel in history; and substituting in its place hostile governments, driven at once and inevitably into mutual devastation and fratricidal carnage, transforming the now peaceful and felicitous brotherhood into a vast permanent camp of armed men like the rival monarchies of Europe and Asia.

The intention of American abolition and its extra-legal tactics was war, with Americans standing “face to face as enemies, rather than shoulder to shoulder as friends.”[15] He told a Virginia audience in 1855 that his “feelings revolted from the idea of a dissolution of the Union” and would be “the Iliad of our innumerable woes” if it occurred.[16] Much like Benjamin Franklin’s 1776 Philadelphia admonition that “we must indeed all hang together, or, most assuredly, we shall all hang separately,” Pierce warned that the Union preserved American liberties and disunion risked their disappearance. Antebellum men must also hang together, or “most assuredly” hang separately.

For Pierce, abolitionist agitation was driven by philosophical and philanthropic abstractions divorced from practical politics, compromise, experience, custom, and common sense. In this, Pierce sounded a Burkean note. Edmund Burke in his Reflections on the Revolution in France suggested that eighteenth century Britons abjure metaphysics when considering government, its institutions, and its laws. Instead, assailing “theorists,” “sophisters,” “enthusiasts,” and “disturbers,” Burke wrote: “I cannot stand forward and give praise or blame to anything which relates to human actions, and human concerns, on a simple view of the object, as it stands stripped of every relation, in all the nakedness and solitude of metaphysical abstraction. Circumstances (which with some gentlemen pass for nothing) give in reality to every political principle its distinguishing color and discriminating effect.”[17] Pierce concurred, denouncing those “[a]rdently attracted to liberty in the abstract” without practical political considerations.[18] On a visit to Philadelphia in July 1853, traveling north to open the New York World’s Fair, he denied the Founding Fathers were theoreticians or philosophers in framing the Constitution: “These men, Sir, of whom you have spoken, who planned here the institutions of a free government, let us remember, were no holiday patriots; they were no scheming philanthropists; they were no visionary statesmen.” They were instead practical politicians, armed with the lessons of history and experience, seeking to carve out a niche for constitutional government in a dangerous world.[19] In 1855, he called abolitionist theories “the modern isms, which were potent with evil, but powerless for good, which could distract and destroy but never construct or adorn.”[20] Their dangerous potential was realized in John Brown’s 1859 raid on Harper’s Ferry, Virginia. “We may all have regarded with too much indifference the swelling tide of reckless fanaticism, but we are not too late to breast it now,” he wrote optimistically in a public letter to an 1859 Boston Union Meeting. Brown’s Raid was the result of these new teachings “still vehemently persisted in, from which it sprung, with the inevitable necessity which evolves the effect from the cause.” Putting philanthropic theories aimed at perfecting society above constitutional law and its orderly processes for compromise might perfect society, but also kill the Constitution which made civil society possible.[21]

The War itself only deepened his convictions on the nature of the Founders, declaring in July 1863: “No visionary enthusiasts were they, dreaming vainly of the impossible uniformity of some wild Utopia, of their own imaginations. No desperate reformers were they, madly bent upon schemes which, if consummated, could only result in general confusion, anarchy, and chaos. Oh, no! High-hearted, but sagacious and practical statesmen they were, who saw society as a living fact, not as a troubled vision.” The error lie with the “third generation” since the Founding, a blundering generation of sorts, who foolishly replaced the Founding Era’s practicality with “the passionate emotions of narrow and aggressive sectionalism.”[22] Pierce, of course, did not include himself as part of the third generation’s indiscretions.

His close friend and fellow Democrat, the novelist Nathanial Hawthorne, aptly described the philanthropic tendency in many of his novels and stories, in terms Pierce would have recognized. His 1843 short story “The Birthmark,” for example, speaks of an alchemist named Dr. Alymer, “a pale philosopher,” transfixed by his wife’s birthmark, “the visible mark of earthly imperfection.” Removing it becomes an obsession, “the tyrannizing influence acquired by one idea over his mind,” and he connives to remove it by having her swallow a potion. His wife Georgiana notes that her husband’s “most splendid successes were almost invariably failures, if compared with the ideal at which he aimed,” but acquiesces to his demands. “Remove it, remove it, whatever the cost, or we shall both go mad!” she yells. She drinks the potion, the birthmark disappears, and she promptly dies. She is now perfect, but also dead.[23] Similarly, Hawthorne’s 1852 novel Blithdale Romance speaks of the failures of a transcendentalist reform-minded commune outside of Boston, where noble theoretical intentions descend into the human reality of jealousy and rivalry. His Life of Franklin Pierce explained the confluence of their ideas well. Some looked at slavery through “the mistiness of a philanthropic theory,” meaning abolition. Hawthorne and Pierce did not. They looked at it through the eyes of a statesman pledged to the Constitution:

The theorist may take [the abolitionist] view in his closet; the philanthropist by profession may strive to act upon it uncompromisingly, amid the tumult and warfare of his life. But the statesman of practical sagacity—who loves his country as it is, and evolves good from things as they exist, and who demands to feel his firm grasp upon a better reality before he quits the one already gained—will likely be here, with all the greatest statesmen of America, to stand in the attitude of a conservative. Such, at all events, will be the attitude of Franklin Pierce… There is no instance, in all history, of the human will and intellect having perfected any great moral reform by methods which it adapted to that end; but the progress of the world, at every step, leaves some evil or wrong on the path behind it, which the wisest of mankind, of their own set purpose, could never have found the way to rectify.

Even in the war years, Hawthorne persisted. In his unpopular 1862 Atlantic article, “Chiefly about War Matters,” the writer lamented, “No human effort, on a grand scale, has ever yet resulted according to the purpose of its projectors…. We miss the good we sought, and do the good we cared little for.” Dr. Alymer killed his wife to remove a birthmark; abolitionists may kill the country to remove slavery.[24]

These concerns point to Pierce’s final contention that abolitionist civil disobedience was ultimately anti-democratic and, to use the political theorist Willmoore Kendall’s apt term, “constitutionally immoral.” Violence and civil disobedience reject the efforts of a democracy to govern itself as it sees fit, and a dissatisfied minority refuses to use proscribed legal-political channels or obey the decisions of political institutions. In short, said Pierce, abolitionist civil disobedience violates “the great doctrine of the inherent right of popular self-government.”[25] Democratic decision-making reflects “the deliberative sense of the community,” explained Kendall, where elected leaders deliberate over policy, come to a conclusion, and hold a vote.[26] If a majority backs a certain policy, it becomes law and a minority obeys despite their opposition. Kendall continued:

They are free, as individuals, free over in the social order, to plead the case for the beliefs that they hold most strongly. Unless they make solemn bores of themselves, we the people will listen to them. They can try through the processes of persuasion to build a consensus around their strongly held beliefs, but one virtue they must cultivate is that of not being in too much a hurry, and another is that of not expecting other people, their neighbors, to give up overnight their own strongly held beliefs.[27]

Democratic self-government cannot exist unless the vanquished abide by the decision of the majority and patiently wait for their cause to persuade and gain support. Activists must “cool their heels until a consensus, expressed either through the amending process or through the concurrence of the three branches, has swung behind, or at least into acquiescence with, what they were proposing.”[28]

If not, there is no “peaceful transition of power” after elections and no continuity of laws and their enforcement, only a brutal Hobbesian extra-legal battle between individuals and interest groups for power. Kendall described this process as a “derailment” of the American constitutional system, where a minority refuse to abide by its rules, “being terribly sure that they are right and everybody else not only wrong, but wrong because of their wickedness and perversity. People who have suffered such a derailment, we understand at once, are not likely to enjoy waiting for a deliberate sense of the community, and are not likely to content themselves with any process of persuasion and conviction. They know they are right.”[29] Autocracy then replaces democracy, and society, in Pierce’s words, dissolves in “the yawning gulf of anarchy and destruction.”[30]

Hence, Pierce repeatedly described two sides of the antebellum political debate: those who abided by and supported democratic decision-making and those who did not and opted for civil disobedience; those who took the Constitution as a compromise and a whole, and those who broke it up into morally acceptable and unacceptable parts. The primary theorist of antebellum civil disobedience was Pierce’s fellow New Englander Henry David Thoreau. In his 1846 On the Duty of Civil Disobedience, Thoreau wrote:

Must the citizen ever for a moment, or in the least degree, resign his conscience to the legislator? Why has every man a conscience then? I think that we should be men first, and subjects afterward. It is not desirable to cultivate a respect for the law, so much as for the right. The only obligation which I have a right to assume is to do at any time what I think right… All voting is a sort of gaming, like checkers or backgammon, with a slight moral tinge to it, a playing with right and wrong, with moral questions; and betting naturally accompanies it… A wise man will not leave the right to the mercy of chance, nor wish it to prevail through the power of the majority. There is but little virtue in the action of masses of men.[31]

But for Democrats like Pierce, if conscience prevailed over democratic rule, and voting was merely a game of chance, we were left with either an anarchy of individual consciences each pursuing a vision of the good or a self-anointed theocracy run by philosopher-kings with superior consciences. Thoreau’s vision rendered constitutional democracy impossible. “If there are provisions in the Constitution of your country not consistent with your views of principle or expediency, remember that in the nature of things that instrument could only have had its origin in compromise,” Pierce explained to a New York City audience in 1853. “[A]nd remember, too, that you will be faithless to honor and common honesty if you consent to enjoy the principles it confers, and seek to avoid, if any, the burdens it imposes. It cannot be accepted in parts; it is a whole or nothing, and as a whole, with all the right it secures, and the duties it requires, it is to be sacredly maintained.”[32] Individual opinions on right and wrong laws or parts of the Constitution must be filtered through the deliberative democratic process, where they will be accepted by citizens as constitutionally correct law or rejected. There are no other alternatives. “It is no matter what our peculiar views may be, or what prejudices may take possession of our minds or hearts. If, as American citizens, we find ourselves constrained by a law higher or more imperative than this law, we then deny the obligations which the Constitution imposes, and can have no just claim to the protection and blessings which it confers.”[33] Selective obedience was not an option and destroyed the very thing the Constitution was written to protect.

Institutions like political parties, assemblies, and constitutions filtered human passions and ideas and measured their worth. This continual, deliberative evaluation of ideas avoided socially and legally destructive doctrines that appealed to individual conscience and a “higher law” over the Constitution, and acted as a check on individuals prejudiced in favor of their own wisdom rather than the needs of the wider community. Pierce and conservative Northern Democrats did not trust individual consciences, appealing to personal morality or Christian higher law, to make responsible decisions for the whole community. This represented a form of sectarian intolerance and religious intrusion into political decision-making. Although Pierce opposed religious discrimination against the Shakers and Roman Catholics, and worked (with mixed results) as an attorney and politician to right this, he also strongly disapproved of religion interfering with politics. Writing to Buchanan in November 1856 after New Hampshire voted Republican, Pierce bitterly explained, “It is certainly no alleviation to know that the mastering power which overthrew our party there was a perverted and desiccated pulpit.”[34] He fumed to a friend in February 1860, “The cant, heresy, and treason fulminated from many of our New England Pulpits Sunday after Sunday on the approach of every general election is really appalling. We are all more or less responsible for the continuance of such treasonable and dangerous teachings—We have given too much countenance to such teachings by our silent presence.”[35] Pierce joined the Episcopal Church in 1865 in part because it “stubbornly and consistently avoided secular and political matters in its preaching,” and the minister of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Concord, New Hampshire never sermonized on current events.[36]

Pierce also believed that rule by conscience rather than Constitution destroyed political institutions and law. There was nothing civil about civil disobedience or selective obedience of the Constitution. Democratic government was impossible if, upon the calls of conscience to disobey, citizens cherry-picked laws amenable to their own ideas of justice and morality. “Let no man delude you with the ideas that our Union has any intrinsic strength independent of the devotion of the people to constitutional right. It is just as strong as that devotion, and with the observance or disregard of constitutional right it will stand or fall,” Pierce told a New Hampshire audience in 1856.[37] He continued the theme in two 1859 public letters: “Shall the fundamental law of the land be obeyed, not with evasive reluctance, but in good fidelity?” “Between political communities, as between individuals, there can be no fraternity without justice. But what does justice enjoin? Clearly, that, if we will enjoy the benefits which the Constitution confers, we must fulfill the obligations it imposes.”[38] The theme was common among antebellum Democrats. President Buchanan concurred: “Should a general spirit against [law] enforcement prevail, this will prove fatal to us as a nation. We acknowledge no master but the law; and should we cut loose from its restraints, and every one do what seemeth good in his own eyes, our case will indeed be hopeless.”[39] The Catholic journalist Orestes Brownson, a New England Democratic contemporary of Pierce, suggested rule by conscience and higher law revolted against legitimate authority: “To appeal from the government to private judgment is to place private judgment above public authority, the individual above the state, which as we have seen, is incompatible with the very existence of government, and therefore, since government is a divine ordinance, absolutely forbidden by the law of God.”[40] Although Brownson went further than Pierce, who would have been uneasy with Brownson’s religious justification, it further illustrates Northern Democratic anxieties over mixing the rule of law with selective obedience.

We may not approve of some laws or how other states conduct their public business, declared Pierce, but workable constitutional democracy demands that we respect their ability to govern themselves. Texas had “social institutions which her people chose for themselves” and the “new territories were organized without restrictions on the disputed point [of slavery], and were thus left to judge in that particular for themselves.”[41] Those who opposed the repeal of the Missouri Compromise,

have never ceased, from the time of the enactment of the restrictive provision [that Congress shall make no law regarding slavery in the territories] to the present day, to denounce and condemn it; who have constantly refused to complete it by needful supplementary legislation; who have spared no exertion to deprive it of moral force, who have themselves again and again attempted its repeal by the enactment of incompatible provisions, and who, by the inevitable reactionary effect of their own violence upon the subject, awakened the country to perception of the true constitutional principle of leaving the matter involved to the discretion of the people of the respective existing or incipient States.[42]

To say democratic decision-making sometimes made errors or legislated bad or even pernicious laws was entirely beside the point—to define democracy this way was to indicate that it was defined by its ends not means. “It is not pretended that this principle or any other precludes the possibility of evils in practice, disturbed, as political action is liable to be, by human passions. No form of government is exempt from inconveniences,” Pierce wrote in 1855. The deteriorating situation in Kansas was not the result of popular sovereignty, but its rejection, “the result of the abuse, and not of the legitimate exercise, of the powers reserved or conferred in the organization of a Territory. They are not to be charged to the great principle of popular sovereignty. On the contrary, they disappear before the intelligence and patriotism of the people, exerting through the ballot box their peaceful and silent but irresistible power.”[43] Again, Pierce depicted a divide with on one side abolitionist civil disobedience unwilling to abide by political and legal decisions it found contrary to conscience and on the other side the “peaceful and silent but irresistible power” of traditional democratic self-government; between “lawless violence on the one side and the conservative force on the other, wielded by the legal authority of the general government.”[44]

Pierce’s description of these two competing ideas points to a central tension within antebellum governance: between democratic self-government and transcendent moral values, or what historian James Huston has called “Democracy by Process” (“a process of people choosing the laws they lived under. Morality in politics was determined by process, not by outcome.”) and “Democracy by Scripture” (“The purpose of government or a democratic society is to obey [the Christian moral] code more perfectly than other forms of government. The success or failure of democracy is thereby gauged as to how far the outcome deviates from the standard of truth, in this case biblical commandments or biblical reasoning.”).[45] In the first, morality appears incidental in order to make democracy meaningful. Certainly Pierce and conservative Democrats appeared to think so; after all, if morality was primary, choice would be secondary, and you would not have popular sovereignty, democracy, or any version of free government, but a theocracy. Huston even describes this type of government as “inherently (morally) relativistic.”[46] In the second, choice seems incidental for humans to live the life God intended, the life with God in grace, or as Huston notes, “as soon as the moral path is described, there is no choice—except to sin, and that represents the negation of a true choice.”[47] This also distinguished conservative Northern Democrats from Southern pro-slavery Democrats as much as it from anti-slavery activists. Both pro and anti-slavery advocates claimed God as justification for their side, slavery as morally right or wrong, and both sought limitations on democracy to secure their ideas. Democracy was incidental to both moralities. Thus, on one hand you have an amoral democracy of citizens, hopefully enlightened and not debauched, and on the other a theocratic aristocracy of ministers and priests making men moral.

But was this tension real? Did Pierce and fellow conservative Northern Democrats (all adherents to some variant of Christianity and its values) align themselves with the forces of amorality and relativism, process without values? Pierce was silent on the subject but, as a point of conjecture, it is unlikely. First, in making fealty to the Constitution a civic religion, the rejection of which would plunge America into a post-Constitutional hell of anarchy and war, Pierce introduced a moral dimension to obeying the law and participating in constitutional processes. Indeed, he condemned 1850s abolitionists and reformers for “moral treason to the Union.”[48] Second, the democratic process wasan expression of moral values—a combination of choice and Biblical morality—in that the only grace worth having was that which was freely chosen. Therefore, popular sovereignty and democratic, constitutional self-government was not an expression of moral ambiguity, but a recognition that grace was a choice and that men must choose it themselves for it to hold meaning. Massachusetts men making Kansas men organize their communities in a particular way would be bad politics; Massachusetts men making Kansas men moral would be bad theology. In one was the absence of freedom and choice; in the other was the absence of moral knowledge and grace. One made man unfree; another made man morally ignorant. Pierce believed popular sovereignty and self-government were essential to both.

This explanation of language and ideas may not redeem Pierce in the eyes of those who see him as a pliant “doughface,” but it restores a degree of rationality to his ideas and those of the conservative Northern Democracy. Armed with historical knowledge and political ideas to match, they surveyed American political geography and acted accordingly. Neither their choices nor their ideas may be congenial to us. What if men, for example, lacked the necessary civil and personal virtues to make prudent choices? Pierce can be rightly criticized for his naïve belief that men, given liberty in a democratic polity to make decisions, would choose grace without the firm authority of ecclesiastical, governmental, and community institutions. His sunny Jeffersonianism contrasts with the human capacity and historical record of choosing poorly. Nonetheless, these were people who took democratic self-government seriously. In a world where the survival of democracy was hardly guaranteed, there is something understandable in that.

This article was originally published at The Imaginative Conservative.

1 Concord Independent Democrat, January 8, 1852; Roy Nichols, Young Hickory of the Granite Hills. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1931, 191-192, Peter A. Wallner. Franklin Pierce: New Hampshire’s Favorite Son. Concord, NH: Plaidswede Publishing, 2004. 187, 220-221.

2 Congressional Globe, January 9, 1838.

3 Daniel Feller, “A Brother in Arms: Benjamin Tappan and Antislavery Democracy,” Journal of American History, 2001, 88 (1), 50; for a discussion of Democratic Free Soil adherents, also see Jonathan Earle, Jacksonian Anti-Slavery and the Politics of Free Soil, 1824-1854. Chapel Hill: University of NorthCarolina Press, 2004.

4 A Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the Presidents, 1789-1897. James D. Richardson, ed. Washington, DC: United States Congress, 1899. V, 359.

5 Ibid, V, 399. The Address was roundly attacked by Republicans and the Republican press as inflammatory and partisan. Pierce’s most recent biographer notes, “It may have been impolitic to use the occasion of his final message for such a partisan attack, but Pierce’s honesty always trumped his political sensitivity. He could not leave the national stage without forcibly stating his views.” Peter A. Wallner, Franklin Pierce: Martyr for the Union. Concord, NH: Plaidswede Publishing, 2007. 297.

6 James Buchanan. Mr. Buchanan’s Administration, 14.

7 Richardson, V, 224-225.

8 New York Times, August 28, 1855.

9 Richardson, V, 343-344.

10 Providence Daily Post, July 7, 1863.

11 New York Times, August 28, 1855.

12 Ibid.

13 Boston Daily Advertiser, October 3, 1856.

14 Richardson, V, 349.

15 Ibid, V, 398-99.

16 Daily Morning News [Savannah, GA], 25 Aug, 1855, quoting from the Vindicator [Staunton, VA].

17 Edmund Burke. Reflections on the Revolution in France. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 1987, 7.

18 Richardson, V, 399.

19 North American and United States Gazette [Philadelphia, PA], July 13, 1853.

20 New York Times, August 28, 1855.

21 Ibid, December 9, 1859; Antebellum Democrats like Pierce, Douglas, and Buchanan had a fixation with Edmund Burke. See Jean Baker, Affairs of Party: The Political Culture of Northern Democrats in the Mid-Nineteenth Century. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1983 and Michael J. Connolly, “‘Tearing Down the Burning House’: James Buchanan’s use of Edmund Burke,” American Nineteenth Century History, Vol. 10, No. 2, June 2009, 211-221.

22 Providence Daily Post, July 7, 1863.

23 Nathaniel Hawthorne. The Complete Novels and Selected Tales of Nathaniel Hawthorne. New York: Random House/Modern Library, 1937, 1021-1033; Also see Gorman Beauchamp, “Hawthorne and the Universal Reformers.” Utopian Studies 13, no. 2 (2002): 38-52.

24 Nathaniel Hawthorne. The Life of Franklin Pierce. Portsmouth, NH: Peter E. Randall Publishers, 2000, 16, 82-83; Beauchamp, “Hawthorne,” 39.

25 Richardson, V, 292.

26 Willmoore Kendall. The Conservative Affirmation in America. Chicago: Regnery Gateway, 1985, xiii, 36-37.

27 Willmoore Kendall. The American Political Tradition. Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press, 1995, 149-150.

28 Willmoore Kendall. Willmoore Kendall Contra Mundum. Ed. Nellie D. Kendall. New Rochelle, NY: Arlington House, 1971, 369.

29 Kendall. Tradition, 143-144.

30 Franklin Pierce to “Dear Friend,” January 20, 1860. Franklin Pierce Papers, New Hampshire Historical Society (NHHS).

31 Henry David Thoreau. On the Duty of Civil Disobedience. Bedford, MA: Applewood Books, 9, 14.

32 The Weekly Herald [New York], July 16, 1853. The emphasis is mine.

33 New York Times, August 28, 1855.

34 Franklin Pierce to James Buchanan, November 20, 1856. James Buchanan Papers, Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

35 Franklin Pierce to “Dear Friend,” February 17, 1860. Pierce Papers, NHHS.

36 Wallner. Franklin Pierce: Martyr for the Union, 365.

37 Boston Daily Advertiser, October 3, 1856.

38 New York Times, December 9, 1860 and December 23, 1860.

39 James Buchanan. Mr. Buchanan’s Administration, 35.

40 Orestes Brownson, “The Higher Law,” The Collected Works of Orestes Brownson, XVII, 9-10.

41 Richardson, V, 346-347.

42 Ibid, V, 348-349.

43 Ibid, V, 349.

44 Ibid, V, 391.

45 James L. Huston, “Democracy by Scripture versus Democracy by Process: A Reflection on Stephen A. Douglas and Popular Sovereignty,” Civil War History, XLIII, 3, 1997, 190.

46 Ibid, 195.

47 Ibid, 193.

48 Franklin Pierce to “Dear Friend,” January 20, 1860. Pierce Papers, (NHHS).