There is a popular theme embraced by many that the uniqueness of Southern culture is explained by its “Celtic” origins in opposition to the “Anglo-Saxon” foundations of the North. This thesis has been expressed strongly in such works as Grady McWhiney’s Cracker Culture: Celtic Ways in the Old South, Jim Webb’s Born Fighting: How the Scots-Irish Shaped America, and James P. Cantrell’s How Celtic Culture Invented Southern Literature.

Should the distinctive and defining features of the South be described and understood as “Celtic”? This is an interesting and important question that deserves exploration. However, there is a more important question to be kept in mind: is the “Celtic thesis” an asset or a liability for those of us who are working to keep Dixie alive and hoping that someday Southerners will regain control of our own destiny?

There is no doubt that certain cultural traits, as expressed in Southern life and literature, have persisted and reappeared over long periods of history. I my humble self have written that Faulkner has resemblance to some antebellum Southern writers, not because of direct influence but simply because he put his bucket down the same well of Southern life as they did. However, the continuity of certain traits, a historian is prompted to suggest, does not necessarily prove that a specific culture has been transmitted whole-hog across centuries—does not prove that “ the South” can be understood as a Celtic culture. It is evident that there is a “Celtic” strain that is resistant to the materialism and abstract thinking of mainstream American society and that it is found among Southerners–but that is a long way from proving that the South is to be defined and understood as a Celtic culture.

A good many of our unsophisticated compatriots who have become devotees of Southerners as Celtic have not even understood the need to define the term. It is not even clear whether to them “Celtic” means a culture, a race, or a language. These three categories are not neatly coterminous. “Celtic” has not been as clearly defined as it ought to be by those who use the term. McWhiney assumed it was the way of life of the non-Anglo regions of Britain, but provides little guidance as to how it was transmitted to the Old South. Also, as I pointed out in a review of Cracker Culture when it first appeared, he describes us crackers entirely from the observations of hostile outside observers and seems to glory in their biased portrayal of our supposed negative traits. Of course Frank Owlsey had laid out the whole Southern herding culture long before McWhiney, though he did not call it “Celtic.”

I have many strong impressions of “Celtic culture.” However, as a historian I do not yet have a systematic account of its description, origins, and historical course. I think the promoters of the Celtic thesis under-estimate the extent to which the Celtic and Anglo or even Anglo-Norman cultures have interpenetrated and mutually influenced each other, over centuries in Britain, and in the formation of the life of the South. For instance, can you draw a distinction between Celts and non-Celtic English borderers? Would Sir Walter agree with that division? How about Lorna Doone, as I recall, south of the border people doing a good imitation of Scots rievers ? William Gilmore Simms may have had Irish forebears, but he is rather hard to separate from the English and Huguenot gentry of Lowcountry South Carolina.

I do not think that such a sharp division can be made between Celtic Southerners and Anglo-Norman Southerners . This seems to me both wrong and as giving aid and comfort to our enemies who want to declare Southern whites as riven by class antagonisms. Both Webb and Cantrell present a South in which Celts are oppressed by an Anglo aristrocracy. Celtic Southernness picks up too much of the enemy’s dogma in seeming to accept a dichotomy between Confederate slaveholding whites and those who did not hold slaves but were fighting for their distinct non-Anglo culture rather than for the South as such. Or perhaps just because they were “Born Fighting.” I can hardly think of anything that more undermines the eternal South than this false division.

Boones and Crocketts and Donelsons and Lytles went over the mountains and when the Calhouns moved into upper South Carolina in the 1770s they had substantial numbers of Negroes already with them and they started exporting as much cotton and tobacco as they could and as soon as they could In 1860 the substantial families even in the mountains were slave owners, as indeed were a fourth of all Southern families and in some states up to a half—mostly small numbers who worked with the family. Southerners were not class -divided between slaveowners and non-slaveowners as our enemies have always insisted. And if they were, it certainly was not a Celt/Anglo division. There was by the late antebellum period a shared identity by Southerners of every ethnic origin, so solid that even newcomer Yankees and Europeans could see and identify with it.

True the Ulster Presbyterians were a strong element in supporting the Revolution in the South, but no more than the gentry and yeomanry from southern England. On the other hand, before and during the Revolution, Scots were notorious Tories—the educated, citified, on-the-make Scotsman being a zealous hanger-on of the English ruling class with nothing “Celtic” about him except maybe an accent—the scoundrel Founding Fathers Alexander Hamilton and James Wilson being prime examples.

A Celtic/Anglo division of the colonial South does not allow for other elements in the formative period. My own little bit of research indicates that Germans were much more numerous in Virginia and the Carolinas usually allowed for and blended quickly into the various British strains. And there were the French, not only in Louisiana but in the whole Mississippi Valley from New Orleans to St. Louis. Anglo and German Southerners hated Yankee Puritans just as much as Celtic Southerners and their opposition to Puritanism was much clearer than the Scots’. On the other hand, the mutual sympathy between antebellum Southerners and oppressed Irish indicates a generous recognition of a similar plight. It does not prove that antebellum Southerners felt a huge ancestral and cultural identity with “Celtic Culture.” True, the Irish and Catholics did not encounter bigotry in the South as they did among the Yankee puritans, but I might argue that had more to do with a a tolerant gentlemanly code of English Episcopalians than with any Celtic inheritance (which was the most anti-Catrholic strain in the South).

Consider that the frontier conditions of America tended to cause a reversion to a type of social organization (tribal, warrior) that was common to all northern Europeans (or for that matter the ancient Greeks) at an earlier stage. Those Anglos from the Low Country and even the Germans moved west and became good frontiersmen too. Something more involved was involved than a transfer of “Celtic culture.” Vast numbers of Irish poured into the North in the 19th century. While many of their descendants made good Americans, there is nothing Southern about these “Celts.” They are wannabe puritans with smarmy writers, oily cardinals, freedom-riding nuns, criminal gangs, and crooked politicians. Why did “Celtic culture” turn out so differently there? How then can we say that Celtic Culture as such particularly defines Southern identity when it made such a negligible or different impact elsewhere?

In the earlier antebellum period there was a literary convention about the older regions of the South being in decay. It is true that there were richer lands to the west and half the population was moving off, so there was a sense of vacancy and nostalgia. The conditions did not indicate decay–that so much of the population was moving west is an indication of a very dynamic people. If they had all stayed home you would have had a static society. Webb in particular presents a picture of a weak older South versus a dynamic frontier. False. Antebellum Southerners of all national origins were a prolific people with large healthy families, meaning resources were strained and it was necessary for many sons to abandon the old home place. That enervated mood described the earlier antebellum period only, in the economic depression after 1816. By 1850 the “Anglo” older South had recovered economically and was in a strong and dynamic condition. By 1860 agriculture had been reformed and revived. Industry was building. Capital was accumulating. Prosperity was rising. Schools, churches were flourishing. How do you think Virginia and the Carolinas sustained four years of total war so well, both in morale and economic productivity?

In fact, it was the very dynamism and prosperity of the South that motivated a destructive Northern envy and hatred that saw little difference among the people of the vast Southern land except an imagined class division that the history of the Confederacy proved to be a delusion.

My real concern is this. Dwelling on the Celtic theme is dividing and undermining the South. Once we have established that the South is defined as Celtic, what have we accomplished? We have excised Southern and substituted Celtic. Our enemies could not ask for anything more. To claim that the real South is “Celtic” is to say, as Webb and Cantrell do, that genteel Anglo-Southerners are inimical to and different from Celtic Southerners. This is wrong historically and factually, but more important it divides up Dixie at the time it needs to be united in a revived self-identification.

Some years ago there was a stupid PBS series on the English language. They managed to portray black dialect as the only distinct speech from the South. (In fact, as Cleanth Brooks showed, the black accent is not African but reflects the speech of the earliest settlers from Southern England, the first North American slaveowners.) According to this silly show presented by a Canadian, the “American” accent is Scots-Irish (here they showed the home of U.S. Grant’s forebears in Ulster). Actual Southern speech was never mentioned but simply portrayed as “American English” even though some of the plain folk actually being recorded kept referring to their Southern accent. In other words, the South as such disappeared into “Celtic” history. Webb’s book serves the same purpose. Rather than celebrating brave SOUTHERN and Confederate fighting men, our attention is directed to brave Celtic warriors who happen to be in the South and explain its history.

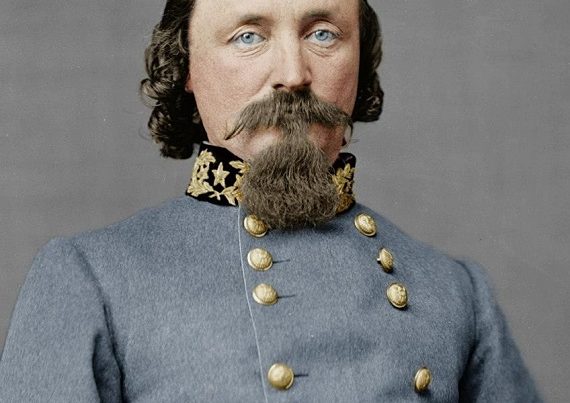

If we are going to celebrate great Celtic warriors rather than Southerners we may as well celebrate Grant, Sheridan, McClellan, Kilpatrick, etc. The whole approach divides up and subverts the identity of our beautiful homeland and noble SOUTHERN people. What about the hard-fighting Southerners with non-Celtic names like Beauregard, Hood, Early, Hill, Hampton, Hardee, Longstreet, Van Dorn, Forrest, Hoke, Pender, Ramseur, Cobb, Ashby, Mosby, and Semmes (Spanish).

America is Southern at its core. Southerners are not an ethnic group except when America is considered only as a mélange of such groups.. We are a people, a nation, incorporating many groups that have been made into one by our history. To be a “Southerner” is good enough for me.