Andrew Johnson was born into poverty in rural North Carolina. His father died after saving some town locals from drowning and left the family to fend for themselves in a two-room shack. A young Andrew began working as a tailor’s apprentice and developed an appreciation for the laboring class early on.

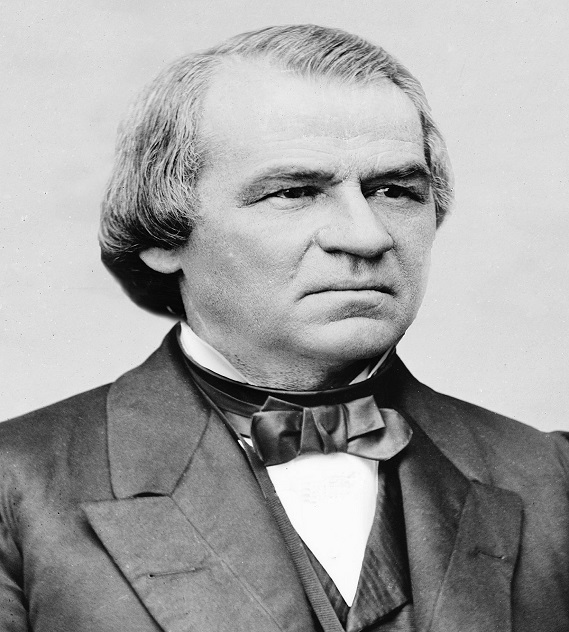

Johnson was poorly educated and learned how to write from his wife, while he was still working as a tailor. The Southern historian Charles Ramsdell Lingley described Johnson as “a compact, sturdy figure, his eyes black, his complexion swarthy” and as a “tenacious man, possessed of a rude intellectual force, a rough-and-ready stump speaker, intensely loyal, industrious, sincere, self-reliant.” His rise in politics was in part due to his firm stance as a states-rights Democrat and ability to identify with the common man. Johnson’s character also frequently became the subject of attack because he would often exchange words with the crowd members yelling out at his speeches and earned a reputation as unrefined and coarse. But by all accounts, Johnson kept his talking points punctual, spoke with power, and knew how to work a room. Probably his biggest criticism before his rise to the office of President was his state of obvious drunkenness at Lincoln’s second inaugural address.

Johnson admired true statesmen, hated politicians, and was most conservative when it came to government spending. He would debate anything that required the expenditure of public funds, having introduced bills to reduce Congressional salaries and even opposed proposals like the Smithsonian Institute because he thought it would be an unjust burden on the treasury. Though he opposed federal government intrusion into the institution of slavery and openly condemned John Brown, he remained a Unionist during the secession crisis because he thought the South should “fight for their constitutional rights under the battlements of the Constitution.” Perhaps his reasoning for remaining loyal, even after the flight of reluctant secessionists like Alexander Stephens and Robert E. Lee, was that he lacked formal education on the Constitution and looked to the example of Andrew Jackson during the Nullification crisis of 1832.

When Johnson faced Reconstruction, he was initially welcomed by Radical Republicans that wanted to punish the South. However, Johnson’s plan differed from Lincoln’s only slightly, favored leniency, and virtually ignored the freed slaves. This put him at odds with the radical plan for the South to be run by a bayonet, carpetbag government. Most narratives portray Johnson as a Southern racist who wanted to deny equality to newly freed slaves. Johnson, however, had stated years before that he supported emancipation and was mostly opposed to the outrageous spending habits of Congress.

On the issue of the Freedmen’s Bureau, for example, Johnson vetoed a bill to make it permanent and then three days later gave a speech where he charged Congress with seeking to destroy the fundamental principles of the Constitution. His exact words were that “There is an attempt to concentrate the power of the Government in the hands of a few, and thereby bring about a consolidation, which is equally dangerous and objectionable with separation.” and that “We find that, in fact, by an irresponsible central directory, nearly all the powers of Government are assumed without even consulting the legislative or executive departments of the Government.” In other words, Johnson had always been against secession, but never envisioned or supported the centralizing tendencies of the Radical Republicans.

In his veto of the Freedmen’s Bureau bill, Johnson explained that opposed it because he was against a military government of the South, against the unlimited distribution of funds to former slaves and their families, and against taking land away from Southerners. In Johnson’s mind, the defeated Southern states were part of the Union and did not need further punishing, and he broke down how virtually every part of the Freedmen’s Bureau bill was incompatible with the Constitution. His main focus was on government spending and the fact that the Constitution was not designed to guarantee any type of special privileges, just basic rights.

Johnson is perhaps remembered best for his impeachment and failed conviction in the Senate. The eleven charges against him centered on four accusations. First was that the dismissal of Secretary Stanton was contrary to the Tenure of Office Act. The reality was Stanton himself helped author this act and it passed in 1867 to forbid the president from removing civil officers without the consent of the Senate, an obvious ploy by the radicals to maintain their own power. Stanton also secretly drafted a law that gave General Grant, who was running the military, a position almost independent of the President.

Second was that the President had declared that part of a certain act of Congress was unconstitutional. This accusation mainly centered around Johnson’s opposition to the Freedmen’s Bureau and ties perfectly with the third main accusation – that Johnson had attempted to bring Congress into disgrace in his speeches. The important thing to remember here is that Johnson did not object to the Freedmen’s Bureau because he hated equality or because he wanted to disgrace Congress, but because the bill gave an unprecedented amount of power to the general government. Johnson described his qualms in an 1866 speech in Cleveland:

“The rebellion commenced and the slaves were turned loose. Then we come to the Freedmen’s Bureau bill. And what did the bill propose? It proposed to appoint agents and sub-agents in all the cities, counties, school districts, and parishes, with power to make contracts for all the slaves, power to control, and power to hire them out-dispose of them, and in addition to that the whole military power of the government applied to carry it into execution…Four million slaves were emancipated and given an equal chance and fair start to make their own support-to work and produce; and having worked and produced, to have their own property and apply it to their own support. But the Freedmen’s Bureau comes and says we must take charge of these 4,000,000 slaves. The bureau comes along and proposes, at an expense of a fraction less than $12,000,000 a year, to take charge of these slaves. You had already expended $3,000,000,000 to set them free and give them a fair opportunity to take care of themselves -then these gentlemen, who are such great friends of the people, tell us they must be taxed $12,000,000 to sustain the Freedmen’s Bureau.”

The fourth and final primary accusation during Johnson’s impeachment was that, in general, Johnson had opposed the execution of several acts of Congress. Interestingly, Johnson’s vetoes all have sound logic and explicitly review how these several acts violated the Constitution. His impeachment trial had more to do with keeping the Radical Republicans unchecked that it did with Johnson’s alleged abuse of power.

In a day and age where conservatism in politics has come down to snarky remarks about abortion, guns, and LGBQT rights, it is refreshing to look back and study a president who took his own power so seriously. As Brion McClanahan recently wrote, “Johnson, in fact, continually upheld his oath of office, making him one of the best presidents in American history.” Today we see our country racking up perpetual debt and engaged in perpetual war, things that Johnson would have undoubtedly been against. Even when his own life was threatened and endangered, Johnson never backed down from his unpopular opinions. With the discussion of secession and nullification becoming more and more mainstream, Johnson’s opinions on the Union might be dated, but modern officials could learn a lot from his conservative politics and pithy style.