Propaganda. It’s a well-known word defined as “information, especially of a biased or misleading nature, used to promote or publicize a particular political cause or point of view.” And, I might add, used for the purpose of demonizing and destroying one’s enemies. The South has had more than its fair share of time in the crosshairs of Yankee propaganda, and one of the most well-known anti-Southern propagandists is James W. Loewen.

But let us not kid ourselves, soft-pedal the truth, or play nice. Loewen is a great deal more than simply a propagandist; he’s a moral crusader seeking to scrub American history of anything that does not fit his progressive worldview and purge our country from its abominable sin of racism. His writings, including the famous, or rather infamous, book Lies My Teacher Told Me, which David Horowitz has called an “extreme and ill-informed polemic,” and the anti-South diatribe, The Confederate and Neo-Confederate Reader: The “Great Truth” About the “Lost Cause,” as well as numerous articles and columns, are, without a doubt, the greatest examples of cherry-picking evidence one is likely to ever encounter.

One does not have to dig deeply into Loewen’s writings to discover that he hates the South, loathes Southerners, and despises our culture, history, and traditions. His world revolves around tearing down our region and our people in books, speeches, and articles in major magazines and newspapers.

Consider this Loewen gem about the “Lost Cause” that appeared in the Washington Post in 2015: “The Confederates won with the pen (and the noose) what they could not win on the battlefield: the cause of white supremacy and the dominant understanding of what the war was all about. We are still digging ourselves out from under the misinformation they spread, which has manifested in our public monuments and our history books.” With such venomous anti-South poison dripping from his acid pen, finding suitable major publications, like the Post, is never a problem.

Although from Illinois, Loewen, at least by his attitudes, surely must emanate from Puritan and Yankee stock. He earned a Ph.D. from Harvard in sociology, not history, and his research field was Chinese-Americans in Mississippi, hardly qualifying one to extrapolate on true Southern history and culture. But, as Southerners well know, self-righteous Puritans believe themselves more knowledgeable than anyone else on any given topic, especially the South.

One of his areas of interest is the seemingly endless and pervasive problem of American racism, and he even taught a semester-long university course on it for many years. His books and articles are filled with lectures on how racist America has been in its past, most especially the South, but that “antiracism” is “one of America’s greatest gifts to the world,” a movement that “led to ‘a new birth of freedom’ after the Civil War.” And by that he means the defeat of the Confederacy and the conquest of the South.

“Race is the sharpest and deepest division in American life,” he writes in Lies My Teacher Told Me. “Issues of black-white relations propelled the Whig Party to collapse, prompted the formation of the Republican Party, and caused the Democratic Party to label itself the ‘white man’s party’ for almost a century.” A Democratic Party that was based almost exclusively in the South, that is.

But simply composing such statements do not make them true. What real historians know is that opinion should be accompanied by corresponding evidence. The Party of Lincoln was no bastion of egalitarianism and also declared itself a “white man’s party” on several occasions, with declarations made by some of its most prominent members.

“We, the Republican Party, are the white man’s party. We are for the free white man, and for making white labor acceptable and honorable, which it can never be when Negro slave labor is brought into competition with it,” said Abraham Lincoln’s Illinois colleague, Senator Lyman Trumbull, a fellow Republican.

Upon accepting the Republican nomination for California governor in 1859, railroad tycoon Leland Stanford made his true feelings known at the party convention. “The cause in which we are engaged is one of the greatest in which any can labor. It is the cause of the white man…I am in favor of free white American citizens. I prefer free white citizens to any other race. I prefer the white man to the negro as an inhabitant to our country. I believe its greatest good has been derived by having all of the country settled by free white men.”

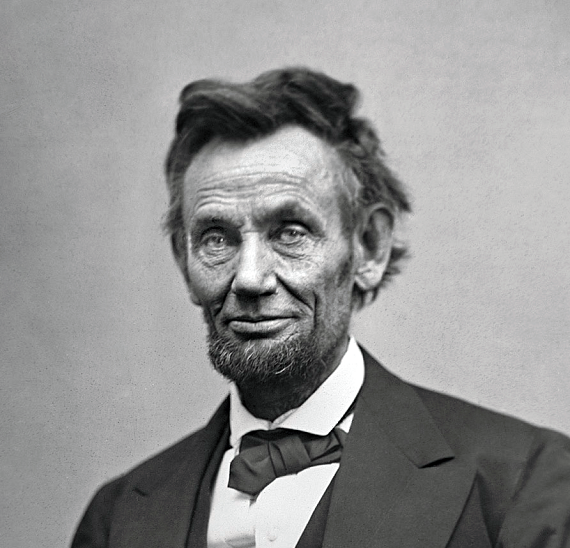

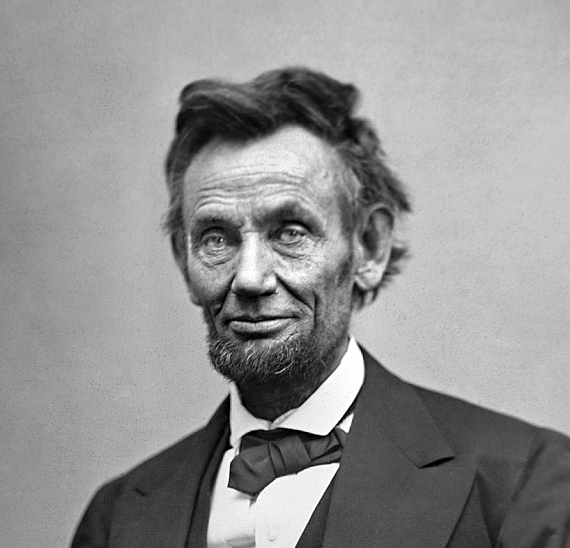

In fact, it was Lincoln himself who made some of the most cringe-worthy racial statements imaginable, a man who wanted to ensure the federal territories did not suffer from the “troublesome presence of free negroes” and sought to keep the black and white races separate in order to spare the country the horrors of racial amalgamation. Such statements would logically make Abraham Lincoln a racist by any meaningful standard.

To be fair, Loewen does discuss, albeit rather briefly, some of Lincoln’s racist feelings but he is very selective in his approach. From the oft-quoted famous remark Lincoln made in one of his debates with Stephen Douglas in 1858, Loewen, in Lies, uses but a few lines of it, so as to give the impression that Lincoln did not extrapolate on the subject as long as he did.

Also missing are Lincoln’s other racist statements. As Lerone Bennett, Jr. has written in his book Forced Into Glory: Abraham Lincoln’s White Dream, “On at least fourteen occasions between 1854 and 1860 Lincoln said unambiguously that he believed the Negro race was inferior to the White race.” There is also no significant discussion of Lincoln’s position on colonization, which he maintained his entire life, or of Lincoln’s pledge to uphold the hated fugitive slave law and seek a repeal of Northern “personal liberty laws.”

But one of Loewen’s biggest deceptions concerns Lincoln and the issue of protecting slavery in the South. As he writes in Lies, “Saving the Union had never been Lincoln’s sole concern, as shown by his 1860 rejection of the eleventh-hour Crittenden Compromise, a constitutional amendment intended to preserve the Union by preserving slavery forever.” Yet, unsurprisingly, Loewen fails to mention that Lincoln, in his first inaugural address, pledged to support the Corwin Amendment, which, like its Crittenden counterpart, was designed to preserve the Union by preserving slavery forever in the South.

Furthermore, Lincoln had been working behind the scenes, as President-Elect, to ensure the Corwin proposal passed both houses of Congress, which it did, and, soon after his inaugural, he sent the amendment to the states for ratification. The rejection of Crittenden’s compromise had everything to do with stopping the spread of slavery into federal territories, and Lincoln’s own letters written soon after his election testify to that indisputable fact.

One could reasonably conclude that Loewen seeks to spare the saintly Lincoln any historical embarrassment (he even sports a Lincolnesque beard), causing him to make statements like this: “In life Abraham Lincoln wrestled with the race question more openly than any other president except perhaps Thomas Jefferson, and, unlike Jefferson, Lincoln’s actions sometimes matched his words.” Pulling down Jefferson to boost Lincoln, a common progressive tactic.

But he does contend that textbooks should discuss Lincoln’s racism (hopefully more than he did in Lies) so that students will understand that “if Lincoln could transcend racism, as he did on occasion, then so might the rest of us.” This makes clear that Loewen believes much the same way Barack Obama does, that racism “is in America’s DNA.” As he writes in Lies, “Slavery’s twin legacies to the present are the social and economic inferiority it conferred upon blacks and the cultural racism it instilled in whites. Both continue to haunt our society.”

The idea, though, that Lincoln transcended racism is laughable to serious scholars and historians. His position on colonization alone explodes that myth. But here are a few questions for Loewen and others like him:

If Lincoln was so anti-slavery in his beliefs and so deeply moved by the plight of black people in America, why was he never an abolitionist? Why did the abolitionists despise him? Why did they refer to him as a “slave hound” who did not have “a drop of anti-slavery blood in his veins”? And, furthermore, what about Lincoln’s August 1862 letter to Horace Greeley, where Lincoln stated that he would be willing to leave all slaves in captivity if that’s what it took to save the Union? Although Loewen characterizes the letter essentially as a political ploy to gain support for the war in deeply Democratic New York City, in reality, when taken with the rest of Lincoln’s record, it is an example of a man who had not the slightest concern for the welfare of the slaves in the South. His “paramount objective,” he stated, was preserving the Union, at least his new version of it.

Judging by Loewen’s vast writings, he appears to be completely consumed by “white guilt,” causing him to exhibit nothing resembling objectivity. As he writes in his Confederate Reader: “White history may be appropriate for a white nation. It is inappropriate for a great nation. The United States is not a white nation. It has never been a white nation. It is time for us to give up our white history in favor of more accurate history, based more closely on the historical record.” This seems like an appeal for a more diverse approach to American history, but given his constant anti-South invective, in reality it’s nothing more than an attempt to scrub textbooks and monuments of anything resembling praise of the South. In fact, Loewen wrote an open letter in 2015 to James M. McPherson seeking to “de-Confederatize” one of his textbooks.

Yet rather than practicing what he preaches, Loewen resides and works in lilywhite Vermont, a state that has one of the lowest percentages of black residents in the Union. According to the latest US Census Bureau statistics, Vermont’s white population, in July 2016, was 94.6 percent, while the black population stood at just 1.3 percent. Loewen’s hypocrisy certainly knows no bounds. But one could only conclude that it is his belief that spending one semester in Mississippi in 1963 during the Civil Rights Movement, as well as his time teaching at one of Mississippi’s historically black institutions, Tougaloo College, where he lived for seven years, would be recompense enough and therefore must qualify him to comment extensively on the South and Southern racism.

Excluding his own contradictions, exposing supposed Southern hypocrisy is a favorite tool of Loewen, and one of his biggest lies involves what he believes is an inconsistency over the doctrine of states’ rights, specifically how the South reacted to Northern violations of the federal fugitive slave law. Since the South now stands on “states’ rights” as the sole reason it chose to leave the Union, Loewen “demonstrates” that the South did not support states’ rights but, in reality, opposed them, at least when it involved Northern states.

It’s a very strange thesis that he espouses in nearly every piece he writes or interview he gives. As he told a host on NPR, the war was “about slavery and it’s against states’ rights.” To that remark, host Robert Seigel, completely on board with Loewen’s theme, chimed in: “Yeah because New York, under states’ rights, would be able to do as you choose.” Except secede from the Union if you are a Southern state, obviously.

So what does Loewen mean? In response to the federal fugitive slave law, first adopted in 1793 and updated in 1850, many Northern states passed what was termed “personal liberty laws,” which, in effect, blocked enforcement of that contentious federal statute. This act of nullification “infuriated” the South, notes Loewen, and all because the North was simply trying to exercise states’ rights. So, therefore, the South was in opposition to states’ rights.

But all Loewen demonstrates is a lack of understanding of federalism, the great political system crafted by America’s Founding Fathers that divided political power between the federal government and the individual states. It is an established constitutional fact that the capture and return of fugitive slaves did not involve states’ rights but was considered a federal issue, and power over it was handed to the federal government in the Constitution.

A simple reading of the Fugitive Slave Clause of the Constitution will clear up any confusion. The clause in question, found in Article IV, Section 2, Clause 3, reads:

“No person held to service or labour in one state, under the laws thereof, escaping into another, shall, in consequence of any law or regulation therein, be discharged from such service or labour, but shall be delivered up on claim of the party to whom such service or labour may be due.”

The key phrase is “in consequence of any law or regulation therein.” That simply means, in legalistic language, that states are prohibited from passing any law or regulation that interferes with the capture of runaways. In other words, state laws matter not.

So, even though we all agree on the wrongness of slavery, the issue fell exclusively in federal hands and the states were prohibited from interfering with it. Furthermore, the US Supreme Court upheld federal exclusivity in Prigg v. Pennsylvania in 1842. So Loewen’s contention that the South violated “states’ rights” by simply criticizing Northern interference with the fugitive slave law is more than a stretch of the imagination; it’s a pathetic attempt to find some fault, any fault, with the South.

Loewen’s writings also contain examples of supposed Southern violations of the Bill of Rights, which were in defense of slavery, he reminds us, but, in reality, are no more scholarly than his other hypotheses. His evidence? The South criticized the North’s abolition societies and their attempts at allowing free blacks the right to vote, as if that was anything more than an extremely rare occurrence, for the evidence tells us that free blacks were treated worse in the North than in the South (some Northern states even refused to allow them to emigrate), and as C. Vann Woodward pointed out in his influential book, The Strange Career of Jim Crow, segregation began in the North before migrating to the South. So there were no direct actions by the South against the North, just mere condemnations.

But one key to unraveling this particular line of attack is the understanding of the Bill of Rights at the time. Until the “incorporation doctrine” came into existence at the turn of the 20th century, most Americans since 1791 understood that the Bill of Rights applied strictly to the federal government, not the individual states. Even the expansionist Marshall Court, in the 1833 case Barron v. Baltimore, held in a unanimous vote that the Bill of Rights did not apply to the states. Of course, for the South to simply criticize Northern behavior is hardly interference or a constitutional violation, yet this is another example of woeful ignorance or a selective use of the basics of history and constitutional law.

The major target, though, for Loewen, and those who seek to demolish the “Lost Cause” as a myth, is the cause of Southern secession and the war. He claims, as they all do, that the South seceded and the war came for one chief reason. “States’ rights was not the main cause of the Civil War – slavery was,” Loewen writes in an article for “Teaching Tolerance,” a publication of the Southern Poverty Law Center. Believing that such a complex affair can be rationalized with a simple explanation is shortsighted and very narrow-minded. But it is necessary to drive their political agenda.

To make his point, Loewen centers on the declarations for secession that a few of the states drafted in their conventions, even though he often implies that all Southern states drafted declarations citing slavery as the sole reason for disunion. He writes in Lies that slavery “was the underlying reason that South Carolina, followed by ten other states, left the Union.” But even though scholars may disagree on reasons for the first wave of secession, the sole motive for the upper South was clear, coming soon after Lincoln’s unconstitutional call for volunteers to invade the new Confederacy. Virginia, Tennessee, North Carolina, and Arkansas wanted nothing to do with Lincoln’s plan and left the Union.

But added to the cause of slavery is one other closely related issue: white supremacy. In Lies Loewen writes, “Black-white relations became the central issue of the Civil War.” The South’s “leaders made this clear,” he reminds us. In fact, he once said on NPR that Jefferson Davis “did commit treason on behalf of slavery and white supremacy.”

And it’s this aspect of “Confederate ideology” that Loewen uses to explain why “so many white southerners – even those who owned no slaves and had no prospects of owning any – mobilized so swiftly and effectively to protect their key institution.” In the Washington Post he wrote in 2011 that “two ideological factors caused most Southern whites, including those who were not slave-owners, to defend slavery. First, Americans are wondrous optimists, looking to the upper class and expecting to join it someday. In 1860, many subsistence farmers aspired to become large slave-owners. So poor white Southerners supported slavery then, just as many low-income people support the extension of George W. Bush’s tax cuts for the wealthy now.” The other factor, of course, was white supremacy.

Though he includes a few cherry-picked quotes from newspapers, he provides not a single scrap of evidence to support his hypothesis that hundreds of thousands of ordinary Southern men sought to become planters and died for the cause of slavery and white supremacy in order to secure a chance at achieving it. Not a single letter or diary entry from an average Southerner admitting to such an ideological belief. Even in his Confederate Reader Loewen includes not one letter from a common Confederate soldier.

Not even James M. McPherson, who is certainly no friend of the South, could go along with such a fanatical and untenable position. As he wrote in What They Fought For, Confederates “fought for liberty and independence from what they regarded as a tyrannical government,” as the “letters and diaries of many Confederate soldiers bristled with the rhetoric of liberty and self-government.”

On this issue, there are more questions Loewen cannot, or will not, answer: If slavery constituted the sole reason the South seceded from the Union, why did it not call off secession and return after Lincoln pledged support of the Corwin Amendment? Why would Jefferson Davis not call off the war in 1862 after Lincoln issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, which ensured that loyal Southern states could keep their slaves? Indeed, before the deadline on January 1, 1863, Lincoln proposed a gradual, compensated emancipation plan, along with a proposal for colonization, that would not see the end of slavery until 1900. Why not accept such an offer? Because slavery was not their sole concern.

But other reasons for secession are generally dismissed, like economics, which was on the mind of many Southerners in 1860. But as Loewen writes, other issues like the tariff “can be dispensed with fairly quickly.” And this is because he leaves out all the evidence. From one of his articles:

High tariffs had been the issue in the 1831 nullification controversy, but not in 1860. About tariffs and taxes, the “Declaration of the Immediate Causes” said nothing. Why would it? Tariffs had been steadily decreasing for a generation. The tariff of 1857, under which the nation was functioning, had been written by a Virginia slaveowner and was warmly approved of by southern members of Congress. Its rates were lower than at any other point in the century.

Knowledgeable historians should pick up on his glaring omission immediately, as Loewen left out the Morrill Tariff Act altogether, a bill signed into law on March 2, 1861, which doubled tariff rates. But even though it did not become law until after the initial round of secession, it had been debated for more than a year before its enactment. In fact, it passed the House in May 1860 as the presidential campaign was heating up. This is important because Lincoln and the Republican Party were pledged to the policy of protectionism and the South knew it.

Interestingly, though, when South Carolina seceded on December 20, 1860, the convention issued an address to the people of the Southern states written by Robert Barnwell Rhett, which Loewen includes in its entirety in his Confederate Reader. So, sitting right in front of him is a document written by a Southern “fire-eater” that begins, not with slavery or white supremacy, but tariffs and taxation, a subject constituting the bulk of the document. Rhett likened the South’s position to that of the American colonies and the North to the British Empire. He wrote:

The Southern States now stand in the same relation toward the Northern States, in the vital matter of taxation, that our ancestors stood toward the people of Great Britain. They are in a minority in Congress. Their representation in Congress is useless to protect them against unjust taxation, and they are taxed by the people of the North for their benefit exactly as the people of Great Britain taxed our ancestors in the British Parliament for their benefit. For the last forty years the taxes laid by the Congress of the United States have been laid with a view of subserving the interests of the North. The people of the South have been taxed by duties on imports not for revenue, but for an object inconsistent with revenue – to promote, by prohibitions, Northern interests in the productions of their mines and manufactures.

The London Times agreed. “The contest is really for empire on the side of the North, and for independence on that of the South, and in this respect we recognize an exact analogy between the North and the Government of George III, and the South and the Thirteen Revolted Provinces. These opinions…are the general opinions of the English nation.”

But that’s not all the evidence Loewen ignores. There was plenty of Southern discontent over economic issues. In November 1860, just days after Lincoln’s election, Senator Robert Toombs spoke before a special session of the Georgia legislature and discussed the economic questions concerning to the South, particularly the Morrill Tariff, then workings its way through the legislative process. Why does the North advocate for the “glorious Union”? Toombs asked. It was very obvious. “By it they got their wealth; by it they levy tribute on honest labor.” The North “will not strike a blow, or stretch a muscle, without bounties from the government.” The existing tariff [of 1857], Toombs pointed out, “was sustained by an almost unanimous vote of the South; but it was a reduction – a reduction necessary from the plethora of the revenue; but the policy of the North soon made it inadequate to meet the public expenditure, by an enormous and profligate increase of the public expenditure.”

At that very moment, Senator Toombs explained to the members, a new bill for higher rates, the Morrill Tariff Act, the “most atrocious tariff bill that ever was enacted,” which had already passed the House, sat waiting in the Senate. “It was a master stroke of abolition policy; it united cupidity to fanaticism, and thereby made a combination which has swept the country.” Abolitionists became protectionists and protectionists became abolitionists. The “robber and the incendiary struck hands,” Toombs noted, “and united in a joint raid against the South.”

Also consider Henry L. Benning’s speech before the Georgia legislature, given a few days after Toombs, that was focused mainly on the economic plight of the South. By being in a Union with the North, Benning noted, the South was being drained of her resources. These “drains,” as Benning called them, which included the tariff and federal internal improvements legislation, was a major reason why “the money of the South is incessantly flowing to the North.” And the only way to end it was through secession. “A separation from the North would cut off all these drains,” thereby allowing the South to enrich itself.

Interestingly, the only time Benning appears in any of Loewen’s writings is as “an ambassador for slavery,” because he traveled to Virginia in February 1861 and gave a speech to the legislature urging disunion and spoke a lot about slavery, an address that is included in the Confederate Reader. Loewen abhors the fact that many military installations are named for former Confederates, in this case Fort Benning in Georgia. “I think we’re the only country that ever named a whole bunch of bases for folks who were on the other side,” he told NPR.

Senator Jefferson Davis also understood the economic threat, which was one of the reasons why the North resisted slavery in the territories so as to add more free states in order to increase their hold on power. “You desire to weaken the political power of the southern states; and why? Because you want, by an unjust system of legislation, to promote the industry of the New England states, at the expense of the people of the South and their industry.”

To historian Charles Beard, this restrictive territorial policy showed that the North hoped to “gain political ascendancy in the government of the United States and fasten upon the country an economic policy that meant the exploitation of the South for the benefit of northern capitalism.” And after the South left the Union, that’s exactly what the Lincoln administration did, as tariffs were raised ten times and Congress passed the Pacific Railroad Act, a national banking law, the Morrill Land Grant College Act, the Homestead Act, and a ban on slavery in the territories, which would soon turn into a full-fledged war on the Plains Indians after the defeat of the South.

The famous Charleston diarist Mary Chesnut recognized the economic consequences of remaining in the Union. She wrote in June 1861, just two months after Fort Sumter: “We want to separate from [New England] – to be rid of Yankees forever at any price. And they hate us so and would clasp us … to their bosoms with hooks of steel. We are an unwilling bride. I think incompatibility of temper began when it was made plain to us that we get all the opprobrium of slavery and they all the money there was in it – with their tariff.”

Even the British, watching the war from across the pond, understood what the war was really all about. As Charles Dickens wrote at the end of 1861, “Union means so many millions a year lost to the South; secession means the loss of the same millions to the North. The love of money is the root of this …. The quarrel between the North and the South is, as it stands, solely a fiscal quarrel,” he wrote in his magazine “All the Year Round.”

There’s so much more that could be covered in Loewen’s voluminous writings but the point is clear and his thesis remains the same: Defend Lincoln and the North, while demonizing the South and, in actuality, all of America. These arguments are re-packaged time and again in any book or article of Loewen’s that one chooses to read.

His goal, though, is not objective truth but to perpetuate a false narrative about the South and to re-write textbooks to teach young Southern students to hate their own history. He writes in his Confederate Reader that “if white Southerners knew what Confederate leaders like Jefferson Davis and Alexander Stephens and neo-Confederates like Mildred Rutherford and Strom Thurmond actually said and did, they would give up these men and women as role models.” And this is his lifelong crusade, but one that has thus far failed.

Sources

James W. Loewen, Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your American History Textbook Got Wrong (New York: Touchstone, 1995, 2007)

The Confederate and Neo-Confederate Reader: The “Great Truth” About the “Lost Cause” (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2010)

James W. Loewen, “‘Why was there the Civil War?’ Here’s your answer.” Washington Post, May 2, 2017 – https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/why-was-there-the-civil-war-heres-your-answer/2017/05/02/1445c796-2f76-11e7-8674-437ddb6e813e_story.html?utm_term=.f0e306ad6e22.

“Why do people believe myths about the Confederacy? Because our textbooks and monuments are wrong.” Washington Post, July 1, 2016 –https://www.washingtonpost.com/posteverything/wp/2015/07/01/why-do-people-believe-myths-about-the-confederacy-because-our-textbooks-and-monuments-are-wrong/?utm_term=.831b34545b64.

“Five myths about why the South seceded.” Washington Post, January 9, 2011 – https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/five-myths-about-why-the-south-seceded/2011/01/03/ABHr6jD_story.html?utm_term=.0fafc14d0ed0.

“Getting the Civil War Right.” Teaching Tolerance, Fall 2011 –https://www.tolerance.org/magazine/fall-2011/getting-the-civil-war-right.

“Rejection of Flag Exposes Larger Truth About the Confederacy.” NPR, July 2, 2015 – https://www.npr.org/2015/07/02/419554834/rejection-of-flag-exposes-larger-truths-about-the-confederacy.

Not at all convinced Loewen was anti-Southern or a propagandist. As a proud descendant of Robert E. Lee’s favorite sister, and someone who teaches others that the Civil War was about more than slavery, I’ve read Loewen’s work and found disagreement with only some of it. The man was sometimes mistaken, but largely fair, and often disappointed with his own party’s attempts to teach history. His book about “Sunset Towns” showed that Southerners were misrepresented and falsely stereotyped, especially in hindsight, because it was actually Northern towns who committed most of the post-war violence against blacks. Conservative Thomas Sowell presents the same cases Loewen did, but with an even more well-rounded eye for historical cause and effect.

I see an emotional reaction from this writer, one less fair and charitable than the so-called propagandist. After all, it was Loewen who advocated for true Southern monuments of the Civil War era to be protected and respected, and he also pointed out in an interview that the South was forced to rely on slavery for longer than it wanted to (because of Northern economic sabotage and moral posturing).

I hope this comment finds you well, and undisturbed, and that you reconsider how polarized we’re becoming.

No yankee State ever freed a slave. The Corwin Amendment was passed AFTER the 7 Cotton States had departed the union. The Corwin Amendment was to ensure a supply of domestic cotton capable of being taxed at the 1860 rate of 25 percent and the 1861 rate of over 40 percent.