Delivered at the 2017 Abbeville Institute Summer School.

The attack on the so-called “lost cause” myth in American history is nothing new. Beginning in the 1950s and 60s, historians like Kenneth Stampp began a concerted effort to undermine the dominant historical interpretation of the War, namely that the War and Reconstruction had been stains on American history, that the War could have been avoided, and that slavery was only a peripheral issue in the entire conflict. Stampp privately wrote that he could never be a “negro-hating Doughface” like James G. Randall or Avery O. Craven, men whom Stampp considered to be some of the worst historians in American history. Why? Because unlike Stampp Craven and Randell did not buy the neo-abolitionist narrative of the events leading to the War. Craven, in fact, placed the War at the feet of a “blundering generation” too foolish to accept compromise to avoid bloodshed. He had no love for Southerners, but he was equally hard on Northern abolitionists. To Stampp, the War had been a moral crusade from the beginning, a conflict that began when Southerners realized the institution of slavery was doomed and the only recourse was secession. Abolitionists were the morally righteous men in white hats destined to save America from the evil slaveocracy. It did not matter that most American viewed abolitionists with suspicion in the antebellum United States, or that their tactics were less than peaceful. What matters is that they won, and the South should be viewed in a far less sympathetic light than the “blundering generation” school accepted.

This is what Stampp had to say to his mentor, William B. Hessetine, in 1945: “I’m sick of the Randalls, Cravens and other doughfaces who crucify the abolitionists for attacking slavery. If I had lived in the 1850s, I would have been a rabid abolitionist. When the secession crisis came I would have followed the abolitionist line: let ‘em secede and good riddance….But once the war came, I would have tried to get something out of it. I would have howled for abolition, and for the confiscation and distribution of large estates among negroes and poor whites, as the Radicals (some of them) did. I would have been a radical because there was nothing better to be. I couldn’t have been a conservative Lincoln Republican and rubbed noses with the Blairs and Sewards; and I couldn’t have been a Negro-hating copperhead. My only criticism of the Radicals is that they weren’t radical enough, at least so far as the southern problem was concerned.” Stampp, along with Eric Foner and others, are often cited as the “objective” historians in contrast to the “Lost Cause” pro-Southern ideologues. Who is telling the truth, here?

We would be foolish to think that Stampp occupied a novel place among American historians. The early postbellum period was littered with historians ready and willing to make the South the ultimate villain in American history, the “peculiar” other offset by the superior and progressive North. James Ford Rhodes multi-volume work on American history is indicative of this type of scholarship. Rhodes believed Reconstruction to be one of the worst episodes in American history, but he held men like Calhoun and Jefferson Davis responsible for the carnage and bloodshed of the War and placed the institution of slavery front and center. Rhodes was not a neo-abolitionist and minimized the role of abolitionism in the coming of the conflict, but he rejected the Southern position that the War had been fought for the principles of 1776 and the right to self-government. Other historians, like the German Hermann von Holst, took the same approach, which is why Southerners believed, and rightly so, that the real war was only beginning.

The War that ended on the battlefield in 1865 began anew with the pen not long after the ink dried at Appomattox Courthouse. Southerners understood the stakes. If the Northern view of the War, now so triumphantly supported by Lincoln’s assassination in 1865, became engrained into American society, there would be no hope of salvaging any promising memory of the Southern people. They would be traitors identified with an institution that the majority of Americans now found morally repugnant. They knew the real story of America, the fact that Virginia was the most important colony and State in the early federal republic, that the South had led the way for much of American history, that their cause of secession was the same as that of the founding generation, and that there was more than just a smidgen of hypocrisy in Northern self-righteousness in the afterglow of victory. But how do a defeated people retain their memory and their character? More importantly, how do the losers help write the story? And it must be noted that the vicious attacks on traditional Southern history we face today are not novel. Southerners in the postbellum period experienced the same thing.

There were two types of Southern historians in the postbellum period, the amateurs and a burgeoning and productive group of well trained professionals. Both aimed to craft a history of the South untainted by Northern views. The first group included people like Mildred Lewis Rutherford of Athens, GA and John Cussons of Alabama.

Cussons penned two little books on Southern history in the late nineteenth century. For thirty-two years he had watched as “Northern friends of ours have been diligent in a systematic distortion of the leading facts of American history— inventing, suppressing, perverting, without scruple or shame—until our Southland stands to-day pilloried to the scorn of all the world and bearing on her front the brand of every infamy.” The South had sat silently, watching as the North explored every avenue to disparage her people, her cause, and her history. In the short period following the War, Northerners had painted the South as the personification of “meanness,” “folly,” and “utter and incurable inefficiency.” The South was the despicable “other” in the American mind, and as a result “The economist with a principle to illustrate, the moralist full of his Nemesian philosophy, the dramatist in quest of poetic justice—in short every craftsman of tongue or pen with a moral to point or a tale to adorn turns instinctively to this mythical, this fiction-created South, and finds the thing he seeks.”

This had broken the unwritten agreement between the two sections following the War. Northerners would acknowledge Lee and Jackson as great Americans and in return the South would consider Lincoln to be the man of hour who saved the Union.

And the South had come to accept it. Her people had been turned against their own history, brainwashed into believing the Yankee version of American history, a history fabricated in the years following the great Southern struggle for independence. Southern children were the targets and as a result “our grandchildren, trained in the public schools, often mingle with their affection an indefinable pity, a pathetic sorrow—solacing us with their caresses while vainly striving to forget “our crimes.” A bright little girl climbs into the old veteran’s lap, and hugging him hard and kissing his gray head, exclaims: ‘I don’t care, grandpa, if you were an old rebel! I love you!’”

This could have been said today.

Cussons understood one of the great maxims of history by quoting the great British historian Lord Macaulay, “a people which takes no pride in the noble achievements of a remote ancestry will never achieve anything worthy to be remembered by remote descendants.” The systematic destruction of the Southern tradition by distortion and lies would render her people impotent in the future. His words were more than quaint “unreconstructed” rants against the government. They were not “I’m A Good Ol’ Rebel.” Cussons wielded a philosophical hammer against Yankee Puritanism in an attempt to save the South from self-loathing, guilt, and shame.

Cussons knew the South, the real South, still existed. It had been defeated in war, but the Southern people had much to admire in their history. Her heroes defended a noble tradition and that tradition, if correctly articulated and saved, would place the South at its proper place in the forefront of American history. Unfortunately, his double-barreled assault on Yankee distortion has been mostly forgotten. His two short works defending the South are not placed among the great tomes of the late post-bellum period primarily because not many know they existed. United States “History” as the Yankee Makes and Takes It and its more substantial sister A Glance at Current History are clear, concise, and more importantly caustic. They are as witty as Bledsoe’s Is Davis a Traitor? or Taylor’s Destruction and Reconstruction and while not as meaty as Stephens’s or Davis’s multi-volume masterpieces on the War and Southern history offer the same defense.

Cussons was born in England and emigrated to North America in 1855. He lived for four years among the Sioux in the Northwest where they named him “The Tall Pine Tree.” He moved to Selma, Alabama in 1859 and became a newspaperman as the half owner of the Morning Reporter. He opposed secession but when the War began in 1861 he served as a commander of scouts and sharpshooters in the Army of Northern Virginia. He was captured at Gettysburg and after his release spent the remaining months of the War out Western theater, eventually fighting with Nathan Bedford Forrest. Following the War he founded a publishing firm, owned a large hunting lodge in Virginia, and served as one of the officers of the United Confederate Veterans.

United States “History” as the Yankee Makes and Takes It was a short work designed to illustrate the growing problem of Puritan history in America. The Puritan, Cussons argued, always considers himself to be the moral superior to any other people. From the beginning, Puritans had formulated the false notion that their customs and traditions produced better men and societies than those of the South. For example, the “Yankee” or “Puritan” idea would logically “formulate and demonstrate” the following proposition:

“1. Patrick Henry, furnished with a good stock of groceries, failed at twenty-three.

2. A Puritan, even of the tenth magnitude, under like circumstances, would not fail at twenty-three.

Ergo: A tenth-rate Puritan is the superior of Patrick Henry.”

This, of course, is a fallacy in logic but one that makes perfect sense to the New England mind.

Cussons defined the Yankee as thus:

Self-styled as the apostle of liberty, he has ever claimed for himself the liberty of persecuting all who presumed to differ from him. Self-appointed as the champion of unity and harmony, he has carried discord into every land that his foot has smitten. Exalting himself as the defender of freedom of thought, his favorite practice has been to muzzle the press and to adjourn legislatures with the sword. Vaunting himself as the only true disciple of the living God, he has done more to bring sacred things into disrepute than has been accomplished by all the apostates of all the ages….Born in revolt against, law and order—breeding schism in the Church and faction in the State—seceding from every organization to which he had pledged fidelity—nullifying all law, human and divine, which lacked the seal of his approval—evermore setting up what he calls his conscience against the most august of constituted authorities and the most sacred of covenanted obligations, he yet has the impregnable conceit to pose himself in the world’s eye as the only surviving specimen of political or moral worth.

Cussons questioned American education, the attempt by the general government–more importantly the Union veterans of the Grand Army of the Potomac–to write a “true” history of the War, and the false narrative that the North had long been opposed to the principles of States’ rights, nullification, and secession.

At every step, Cussons defended the men and the cause of the South and lamented that her history was being written by the victors. “The whole story of the war and its causes,” he wrote, “has been distorted and perverted and falsely told. Yet at the bar of unbiased history, before the tribunal of impartial posterity, it will become manifest that the vital principle of self-government—the world’s ideal, and what was fondly deemed America’s realization of that ideal—went down in blood and tears on the stricken field of Appomattox. It was there that Statehood perished. It was there that the last stand was made for the once-sacred principle of ‘government by free consent.’” The old republic of the founding generation was buried by Puritanical self-righteousness. Cussons predicted the inevitable outcome:

“Potential classes are now longing for a change; they are earnest in their desire for what they call “a strong government.” And it may be that their yearnings will not be in vain. The corruption of a republic is the germination of an empire. A period of domestic turbulence or foreign war would render usurpation as easy as the repetition of a thrice-told tale. Political speculations would then reassume their old names—incivism, sedition, constructive treason—and the familiar remedies would be applied—press censorship, the star chamber, lettres de cachet, and bureaus of military justice.”

In the final chapter of A Glance at Current History, Cussons addressed the relationship between the Indian tribes and the general government and compared the plight of the Indian–harassed, chased, threatened with extermination–with that of the South during and after the War. He recoiled at their treatment and bristled at attempts to make them “good people.” How would it sound, he asked, if the Indian said in response to the bloodthirsty General Philip Sheridan that, “There is no good Yankee but a dead Yankee?” Like the South, the Indian had a noble heritage that was being trampled by an invading army. Cussons believed the two shared a common cause.

Like Cussons, Rutherford was not a trained historian, but also like Cussons had a firm grasp of the Yankee problem in postbellum America. Rutherford, however, was a leading figure in the establishment of the United Daughters of the Confederacy and was the historian general of that organization. It is true that Rutherford made mistakes in her histories, and she is often castigated for her “romanticized” version of the antebellum period, particularly of race and slavery (positions that are unfashionable today but were bolstered by the professional historians of the time), but Rutherford also made several good contributions to Southern history most often by using the words of Northerners to support her arguments. Her often vilified Truths of History is a collection of primary documents designed to defend the Southern view of government and society with Northern voices. This is an artful tactic that can still be used today.

Rutherford took seriously the concern of author and diplomat Thomas Nelson Page—another vilified figure from the New South—that “In a few years there will be no South to demand a history if we leave history as it is now written. How do we stand today in the eyes of the world? We are esteemed ignorant, illiterate, cruel, semi-barbarous, a race sunken in brutality and vice, a race of slave drivers who disrupted the Union in order to perpetuate human slavery and who as a people have contributed nothing to the advancement of mankind.” Again, could not the same words be written today? Rutherford insisted that Southerners study their own past to combat what we would call cultural Marxism today, or the Yankeefication of American history. And Southerners responded. The late nineteenth and early twentieth century witnessed a resurgence of interest in Southern history, particularly from native Southerners. Most, including Rutherford, wanted to place the South as the pivotal section in the founding of the American “nation.” As Northerners ran around telling students that the Pilgrims invented American democracy and all great intellectual, cultural, and technological innovations came from the North, Southerners pushed back, with a new breed of professional historians leading the way.

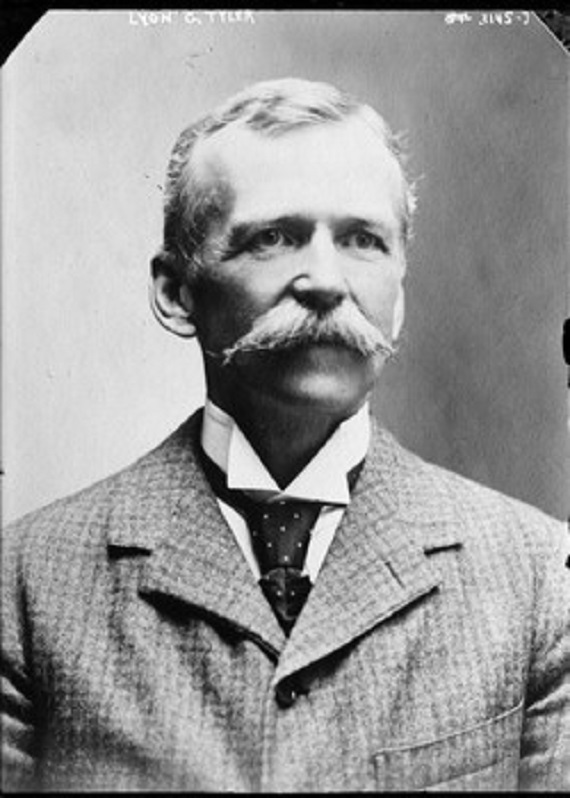

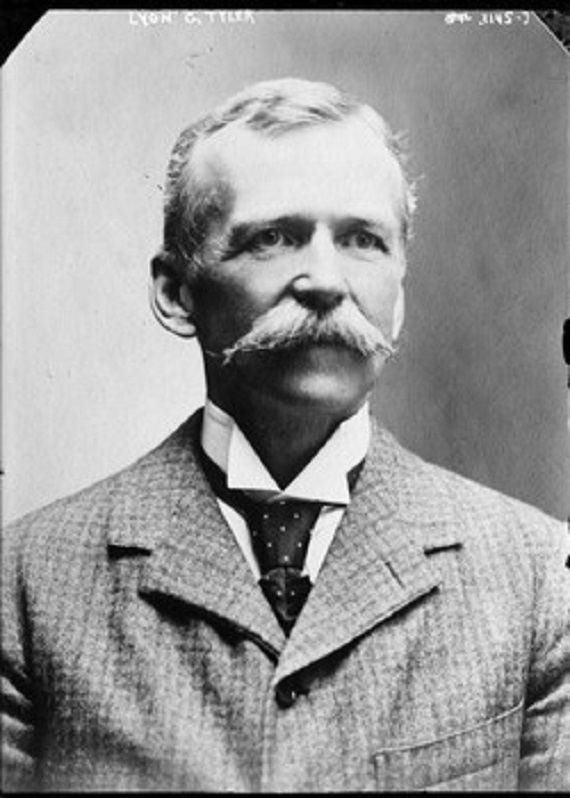

The South in the Building of the Nation series was published in 1909 as both a counterweight to the Northern mythmaking of American history and an affirmation of the South’s role in the establishment of the United States. The title gives away the intent of the project. Southerners were not content to be the backwater of American civilization, the “peculiar” others; they were the primary builders of that civilization, from the founding period to the early 20th century. The series can be viewed as a companion to the Library of Southern Literature and like that series the editors and contributors to The South in the Building of the Nation were a veritable who’s who among Southern historians in the early twentieth century. Several university presidents and leading Southern historians participated with no historian born or bred north of the Mason Dixon among the list. Some recognizable contributors and editors include Franklin L. Riley, the founder of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, U.B. Philips, for a time the pre-eminent American historian on slavery and plantation life in the South, George Petrie, the first Alabamian to earn a Ph.D and the founder of the Auburn University history department, graduate school, and most importantly for many in that state, the Auburn football team, Walter Fleming, a member of the “Dunning School” of Reconstruction and the editor of the important but now out of favor Documentary History of Reconstruction among other works, Samuel Chiles Mitchell, president of several universities across the South including the U. of South Carolina, Edwin Mims, professor of lit at Vanderbilt and primary advisor for almost every one of the fugitive agrarians, Douglas Southall Freeman, the distinguished historian and author of multi-volume biographies of Lee and Washington, and two important presidents of the College of William and Mary, J.A.C. Chandler and Lyon Gardiner Tyler, the latter of the two being the focus of a later portion of this talk.

Like many of the histories produced during this period in the South, The South in the Building of the Nation is often ridiculed for its open racism and glorification of the Old South, but these attacks are often leveled by people who have never read any of the volumes. Like U.B. Phillips and the Dunning School of historians, they are often flippantly discarded by establishment historians and graduate students while much of the fundamental material has not been disproven only re-interpreted by later generations. That is the key to understanding the current situation. The fight is against interpretation not fact, and as any honest historian will tell you, most of history is just that, interpretation. The progressive historian Charles Beard, for example, never said he had the interpretation of the Constitution, it was an interpretation. This is why graduate students used to study historiography. Now they study fashionable trends without digesting who wrote history or why a particular history was written. That is often as important as the material itself. There are, of course, exceptions to this rule. One of the better is John David Smith’s Slavery, Race, and American History where he criticizes “contemporary scholars” who “pay insufficient attention to the contributions of their intellectual forefathers, especially those with whom they disagree ideologically….”

It is true that most, if not all, of the contributors of this series were “racist,” but so was most of America in 1909. They had commonly held views for their time, but the charge of racism is an anti-intellectual statement designed to smother or blacklist a currently unfashionable belief, study, or program. Many of these men were progressives who also viewed the South as important part of American civilization moving forward. One contributor, Peter J. Hamilton, served as a federal judge in Puerto Rico; another, Colyer Meriwather was an American advisor in Japan; and Mims became an outspoken opponent of lynching in the South, and later served as president of what is now called SACS, a regional accrediting body for Southern colleges and universities. Several of these men held leadership positions in colleges and universities across the South well into the mid-twentieth century. The history contained in these volumes is perhaps the best expression of the Southern mind in the early postbellum period. That alone should make it worthy of study, but that would also require a careful examination of the material without the lenses of presentism, something the current academic profession seems almost unable or unwilling to do. In short, these volumes cannot simply be written off as some quaint “lost cause” fabrication of American history or a “white supremacist” polemic. They are a serious academic exercise in a solid narrative format, a thorough and at times critical examination of the South’s role in the American experience and an attempt to understand all facets of Southern history, political, cultural, and economic with the evidence available to them.

Two volumes, in fact, are dedicated to Southern economics, something that had not been comprehensively studied since the late antebellum period. One section on “Free Contract Labor in the Antebellum South” plowed new ground in telling a sympathetic story of free black labor before the War, a field that in 1909 was virtually non-existent. This section, by the way, was written by Alfred H. Stone of Mississippi, a man now regarded as one of the more virulent racists in the South but in his day was so well received as an economic historian that he was appointed as a research associate at the Carnegie Institute of Washington. The aforementioned Smith wrote a very good essay on Stone in his Slavery, Race, and American History.

Yet, while Phillips, Freeman, and Fleming still receive attention from the modern academic community, even if insufficient, one of the contributors to this series, Lyon Gardiner Tyler, has been either ignored or ridiculed by the modern academy and the public at large. The reason? Tyler did not confine his efforts to academic history. He would often engage the popular press—and by engage meaning take them head on when they were wrong—and write histories intended for consumption by the masses. In other words, Tyler took seriously his role as a historian for the people, not just academics. This is what the late Shelby Foote used to tell anyone who would listen. Historians need to learn how to write.

Tyler was the second youngest son of President John Tyler’s and as such a fervent son of Virginia. In addition to being the President of the College of William and Mary, Tyler spent much of his career writing popular histories of Virginia from the colonial period to the present day. He wrote and edited “Tyler’s quarterly historical and genealogical magazine,” which is a fine collection of stories related to all elements of Virginia history. Some of these works were little more than pamphlets for mass consumption. For example, his “Virginia First,” also published at the Abbeville Institute website, is a collection of fifteen points designed to place Virginia at the forefront of American history. As he wrote in his first point, “THE name First given to the territory occupied by the present United States was Virginia. It was bestowed upon the Country by Elizabeth, greatest of English queens. The United States of America are mere words of description. They are not a name. The rightful and historic name of this great Republic is “Virginia.” We must get back to it, if the Country’s name is to have any real significance.” The rest of the little essay follows this trend. Virginia had the first representative government, the first thanksgiving, was the first to declare independence, the first to agitate for independence, the greatest of the early American statesmen and leaders and gallant sons who served with distinction throughout American history. Tell that to the tour guides at Plymouth and they will give you a curious look of bewilderment. Don’t you know that Plymouth was the first at everything?

Tyler was also responsible for an essay that ran in Time magazine in June 1928 entitled “Tyler vs. Lincoln.” In April of that year, Time ran an article comparing Abraham Lincoln to John Tyler. As you might image Time found Tyler to be lacking, calling him “historically a dwarf.” It must be understood that modern Lincoln worship and disdain for the South did not begin in the modern age. L.G. Tyler responded in a splendid little rebuttal. Tyler wrote that “real history cares nothing for the blare of trumpets and the shouts of propagandists….” He then surgically sliced apart the Lincoln myth in a way that few historians have been able to do. Tyler wrote, “In conducting the war Lincoln talked about “democracy” and “the plain people”, but adopted the rules of despotism and autocracy, and under the fiction of war powers virtually suspended the Constitution. This surely cannot be said of John Tyler, as president, who, though of parentage much higher in the social scale than Lincoln, was a much greater democrat, since he professed faith in the Constitution and would not violate it, even at the dictation of his party.”

Tyler attacked Lincoln’s career as a lawyer by claiming that Lincoln made dirty deals and underhanded moves to secure victory for his usually well financed clients. This extended to his political career where Lincoln so vigorously pursued office that he cared little as to how he obtained a seat in Congress, or ultimately, president. Whereas John Tyler assumed the office of president after several brilliant terms as a United States Senator, Lincoln was nominated because he was slick and was able to appeal to everyone and no one at the same time. In other words, Lincoln was a politician and Tyler a statesman. Tyler sought peace and avoided war with Mexico during his administration through expert diplomacy with both the British and the Mexican government, something Lincoln entirely avoided in the time leading to the disastrous conclave through arms between the North and South from 1861-1865. Lincoln professed peace but never showed the resolve to see it through. Tyler, even in 1861, sought peace until it became clear that the Lincoln administration had no interest in a bloodless solution to the conflict. Tyler correctly shows that Lincoln’s entire program was directed toward war from the minute he assumed office in March 1861. This would be considered “Lost Cause” mythology today—and several of Tyler’s critics have labeled it that—but the evidence is clear that Lincoln went headfirst into war when other options were on the table.

Perhaps the best part of Tyler’s piece is his explanation as to why the tariff issue was important in 1861. It was not because, as several modern historians like to suggest, the South paid more in tariff revenue than the North, but because the newly crafted Southern tariff would be less than half of the tariff of the general government, thus creating a competitive economic environment that the North would lose. Lincoln was not concerned about “losing his revenue” because Southerners were out of the Union and thus could not buy Northern manufactured goods. He was concerned about “losing his revenue” because the miniscule Confederate tariff would undercut the North and shift trade to the Southern confederacy, thus destroying the Northern economy. We should stop saying “Southerners paid 80 percent of the tariff” and start outlining the real economic motivation behind Lincoln’s insistence that the South remain in the Union: Northern financial interests could not compete with a vibrant free trade federal republic on their doorstep. Again, this is written off as a “lost cause” myth and establishment historians can sit on television and make stupid statements like, “No one was talking about the tariff” in 1861 when as Tyler clearly shows they were.

But this is only scratching the surface of Tyler’s supposed “lost cause” mythology. According to the critics, Tyler’s most substantial contribution to the “lost cause” myth was his 1920 A Confederate Catechism. The Catechism received quite a bit of press in May of this year with several mainstream and leftist media outlets running pieces on its modern influence or lack thereof. The Catechism is still used by some SCV camps as an educational piece and certainly has historical worth. Critics won’t agree, but remember, the current assault is over interpretation. The Catechism does outline several points that critics view as both illogical and ahistorical, not the least of which is Tyler’s minimization of slavery as a cause of the War. It is also denounced because of its format, but most modern academics equate catechisms to solely religious functions, not realizing that many “history textbooks” used a catechism format in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Mathew Page Andrews, for example, used a catechism format for his very popular United States history textbook, a work that was adopted by hundreds of schools across the United States. Rote memorization was the standard method of historical learning until the 1960s when it fell out of fashion. Better to learn theories and trends than actual people, places, dates, and events, unless of course those people, places, dates, and events correspond to a revised version of America.

Tyler contends that the Northern invasion of the South started the War, that Lincoln purposely broke the peace between North and South when he invaded Fort Pickens—not Sumter—that Lincoln did not wage war to “free the slaves,” that the South had long been the “milchcow” of the North and that secession was true “government of the people, by the people, and for the people.” These positions are simply heresy to the Lincoln mythmakers, and accordingly Tyler, like the Southern historians of the early 20th century, has come under attack for being a liar, a mythmaker, and worse a racist.

But this is why the New South needs more attention. Could every one of Tyler’s 20 points in his Catechism or his 15 points in Virginia First be validated? Could modern historians learn from L.G. Tyler, or how about Cussons, or Rutherford, or the dozens of professional historians like Phillips or Fleming, or pro-amateurs like Stone? I think the answer is definitively yes. More importantly, can the New South be as vital to the understanding of the Southern tradition as the Old? Did men like Dabney and Mencken or even the Agrarians fail to entirely understand the influence of the Old on the New? Could the New have prospered without some of the ways of the Old, and was the race question the only element of Southern history in the 20th century that made it unique? In other words, were Southerners just good racist Northerners? In essence, the narrative goes take away race and Southerners are as bland, corrupt, and money hungry as a New England Yankee, only more violent and with less real culture. It was only race that made them unique. That would seem to be the assumption, but I think a tremendously incorrect one.

My goal in these two lectures has been to pique your interest as historians, philosophers, writers, and scholars in the New South, to seek to understand this period and save it from the clutches of the carpetbagger dominated “Southern studies” programs that now dot the landscapes of the Southern academy. Their goal is to condemn and “contextualize,” to sell a myth to the American public that these Southerners were corrupt and deceitful without remorse or compunction for the sin of secession and sectionalism. Those are modern value judgements, and their myth is even more whimsical than the “lost cause.” As Alfred Stone wrote in The South and the Building of the Nation, “Southern history, as told by Southern people, may be full of myths and ill-founded traditions; but, as it has thus far been written by historians of other sections, it is replete with interpretations and conclusions almost fantastic and apparent efforts of the imagination.”