There are many examples of heroism that illustrate spiritedness in America’s history. Indeed, the American Revolution was won because of the indomitable spirit of the Patriots and a growing unwillingness of the British to put down the campaign for independence. The same spirit was present a century later during the War between the States. It is routinely acknowledged that Confederate commanders such as Robert E. Lee and Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson have achieved a significant place in American history for their military elan.

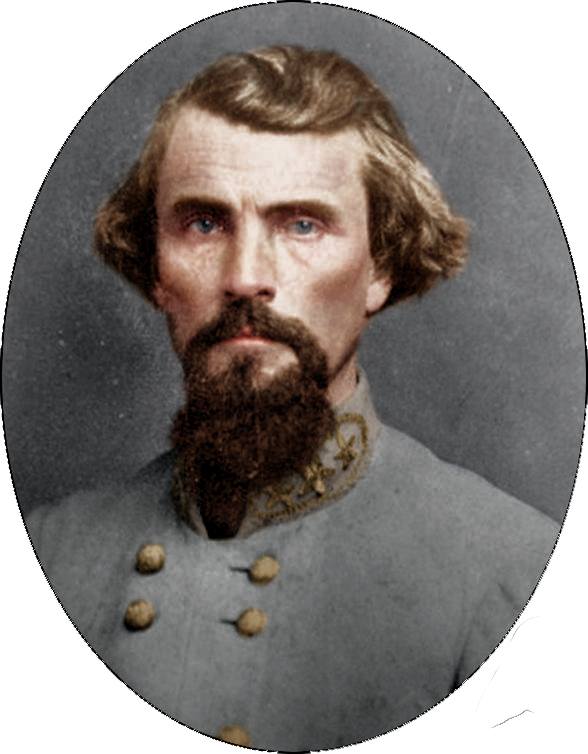

While Lee and Jackson immediately come to mind as exemplary leaders, perhaps the ultimate Southern military genius was an unschooled man of the Tennessee frontier. General Lee was to remark after the War that his greatest soldier was a man he had never met whose name was Forrest. And it was to this Achilles of the Confederacy that Andrew Lytle turned to begin his career as a writer. Certainly Bedford Forrest and His Critter Company appeals to the military historian, but additionally Lytle adds an important mythical dimension to Forrest’s career. Lytle sees in Forrest the heroic summation of nationalism and leadership; he shows both to be patriarchal and familial and, thus, reflective of the fundamental character of the Southern nation and the now obscure form of Confederate nationalism it represented.

By contemporary standards, the attributes of a “clan” nation, or as Lytle has recently remarked “a republic of families,” may be obscure or virtually inaccessible. The roots, however, of such a political hegemony are as old as Homer and Virgil and as relevant as the underground nationalism of contemporary Poland. Lytle reveals in his Forrest biography how a familial nation functions when faced with a formidable military adversary.

What separates Lytle’s narrative from the sometimes dry reporting of military historians is the image of a Southern “republic of families” that runs throughout and, indeed, that unites all of Lytle’s work. In the Forrest biography the family is concrete. “Blood brotherhood” in the connections of kin becomes a “national” brotherhood of Southern families in Forrest’s commands during the war. Lytle writes that Forrest’s rule “maintained the feeling that the South was a big clan, fighting that the small man as well as the powerful might live as he pleased.”

What provides the narrative momentum in Lytle’s Bedford Forrest and His Critter Company are the conflicts that arise when the normal course of this “big clan” is disrupted. Four principles govern the functioning of the Southern family: (1) A hierarchical structure as the basic government; (2) self-sacrifice of the individual members in fulfilling the demands of love; (3) identity of the clan that separates it from the otherwise faceless masses: and (4) the memory of past deeds, practices, and rituals that set standards for coming generations of the blood.

In order to understand the Confederate clan led by Forrest and thereby the essential character of the Southern folk nation, we must grasp what Forrest ultimately represented. In looking at Southern history today, distortions generated by the media and inaccurate portrayals of ante-bellum society make the task formidable. Modern perceptions of the pre-war South for the most part are silly cartoons of that society. Of course, the familiar image of the Southern “red-neck” as a violent, illiterate bigot has become a powerful symbol that is often invoked in talking about the South and appears regularly in car commercials on television. Along with this, the dominant image of the exploited slave is likewise prevalent-angelic and long-suffering. The stereotypical feminine slave is usually the object of a lascivious owner while the male is often portrayed as a brooding, black Adonis who inspires the prurient imagination of the “Southern belle.” Finally, the picture of the selfish, superficial, shrewd, yet elegant plantation owner rounds out these common myths. While such perceptions are current in viewing the South, the facts present quite a different picture, one that is not nearly as sensational, violent, or decadent.

It is difficult to imagine a successful box office draw that would rival Gone With The Wind or Roots based, for instance, on the “Plain Man” Southerner. Lytle’s Agrarian colleague, Frank Owsley, remarks in his splendid study of the Southern yeoman, Plain Folk of The Old South (University of Chicago 1965), “The great mass of several millions were not part of the plantation economy. The group included the small slaveholding farmers; the slaveholders who owned land which they cultivated; the numerous herdsmen on the frontier, pine barrens and mountains; and those tenant farmers whose agricultural production, as recorded in the census, indicated thrift, energy and self-respect.” From this group a large number of Southern leaders came, including John C. Calhoun and Alexander Stephens, the Vice-President of the Confederacy.

As Lytle shows in his book on Forrest, the plain man’s place and role in Southern society has never bee n understood adequately.

Writing in the Forrest biography, Lytle tells us:

There were some four million of them living in the hill country, on the borders of the plantations, in the newly settled states like Arkansas and Missouri. The only difference between them and the cotton snobs was that of a generation or two, and the difference that the rich snobs were ashamed of their pioneer ancestry and they were not. Davis (Jefferson Davis) and his advisors made one great mistake that overshadowed all of the other errors of policy: they chose to rest the foundations of the Confederacy on cotton and not on the plain people.

Consistently in his political essays, Lytle emphasizes this fundamental understanding of the loose association of folk. He writes in “The Hind Tit” (his contribution to the Agrarian manifesto I’ll Take My Stand) that “the South, and particularly the plain people, has never recovered from the embarrassment it suffered when this class was destroyed before the cultural lines became hard and fast.” In the published discussion of Southern Agrarians entitled Fugitives’ Reunion: Conversations at Vanderbilt, 1956 (Vanderbilt Press, 1959) Lytle states that the yeoman farmer was “The basis—finally and ultimately-of what any American society was; that any aristocracy we (the South) had was certainly a homespun aristocracy.” Frank Owsley echoes this same understanding in Plain Folk of the Old South:

The term “folk” has for its primary meaning a group of kindred people, forming a tribe, a nation; a people bound together by ties of race, language, religion, custom, tradition, and history. Such a common tie we call folkways. A folk, thus, possesses a sense of solidarity and is quite different from a conglomerate mass of people.

Owsley’s and Lytle’s views of the Southern nation are prophetic, given the contemporary international realities. Owsley’s use of the word “solidarity” to describe Southern nationalism is haunting, given the valiant example of the Polish people to assert their national identity in opposition to abstract control by the Soviet State. Similar conditions were present in the drive for Southern autonomy.

Lytle examines, in Forrest’s military career, an increasing tension between Forrest’s achievements and how they were perceived by his superiors. The fundamental tension is between the nationalism that Forrest time and again inspired on the battlefield and the isolated, abstract, and often prejudicial views of his superiors, General Braxton Bragg and Jefferson Davis, who unfortunately listened to Bragg’s counsel.

The geographic area of Forrest’s many victories formed an emergent nation composed of Middle Tennessee, Southern Kentucky, and Northern Mississippi. This area comprised the heartland of what was a folk nation. Significantly, Forrest won battle after battle in this area even though much of it was Federally occupied or (as with Kentucky) was part of Union territory. Lytle concluded that “History would ignore the importance of western battles. But it was there that the war must be won and lost, for the heart of the Confederacy lay in the lower South between the mountains and the Mississippi River. To lose Tennessee permanently was to lose the cause, since Tennessee was the strategic center of the whole defense.” Implicitly in all of his writings on the subject (including some pointed remonstrances of Lee), Lytle insists that so total a focus on Virginia was the major strategic flaw of the Confederate high command.

According to Lytle, the failure of the Confederate administration to understand Forrest’s patriarchal rule of the Confederate West occurred in at least three major military situations. First was the needless surrender of Fort Donelson early in the war; second, the unbelievable maladministration of the Battle of Chickamauga; and third, the failure to coordinate Forrest properly against Sherman, who as a result late in the War, waged a notorious military campaign against the Southern population because there was no other policy that could neutralize Forrest except one of demoralization and fear waged on noncombatants by a predatory army.

First, the surrender of Fort Donelson in the winter of 1862 presents a pattern that was to be tragically amplified in later events of the War in the West. Giving up the stronghold would, in effect, open the whole of Tennessee to the Yankees. Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston wrote, “All the resources of the Confederacy are now needed for the defense of Tennessee.’’ Soon a series of Union placements and movements convinced the commanding Confederate officers—Floyd, Buckner, and Pillow—who had all been trained at West Point, that they must surrender or sacrifice their army in trying to defend the Fort. Forrest was not so deluded because of his own scouting of the enemy. Yet Floyd planned to sacrifice his army to an enemy bluff. At this, Forrest protested by telling his superiors that “he had not come out to surrender. That he had promised the parents of his boys to look after them. That he did not intend to see them die that winter in prison camps in the North. That he would not surrender if they would follow him out. That, in fact, he was going out if only one man followed.” Forrest informed his men of his plans and, despite freezing cold and exhaustion, led them out himself. His determination and willingness to take the risk of his own judgments instilled in his troops a confidence (Lytle tells us) “which neither time nor event could shake. A soldier is eager and willing to follow a leader in the tightest places only so long as he believes that the leader can get him out again.”

What Forrest showed was the leader’s solicitude for his men manifest in paternal rule. On the other hand, the surrender of Floyd, Buckner, and Pillow evinces what was to become a mark of certain Confederate commanders: an increasing tendency to neglect the clannish nature of the Confederate armies in deference to a more abstract approach to strategy that, by its nature, neglected this most fundamental property of the butternut forces.

But the failure to recognize this unusual property becomes even more pointed in the extraordinary sequence of events at the bloody battle of Chickamauga in September, 1863, the outcome of which virtually doomed the Confederate West. The situation at Chickamauga can perhaps be paralleled with President Truman’s disastrous removal of General MacArthur from command in Korea, as he remonstrated that there was no substitute for victory; or the grossly distorted reporting of the American media of the Vietnam Tet offensive that had American forces suffering great losses when actually they had successfully resisted the enemy attacks and had seized the momentum of battle. Lytle suggests that the Chickamauga scenario presented a situation that up until that point in military history was unparalleled: a commanding general whose forces were victorious suffering from the delusion of defeat.

General Braxton Bragg, commander of the Confederate armies in the West, repeated on much larger scale the errors of Fort Donelson. General Pete Longstreet (who would later be criticized for his delay at Gettysburg) had thought the loud rebel yells sufficient to convince Bragg of the Southern victory. After the success of the first day, of what was to be a two-day fight, Longstreet never sent word of Confederate supremacy to his superior. The Federals led by Rosecrans had retreated in disorder to Chattanooga. Forrest, whose men had been heavily engaged, viewed the enemy disorder from a Union observation post on the morning of the second day. He immediately wired Bragg of the Union chaos. It was imperative that the Confederates rout the Federals and capture their supplies. No word came from Bragg.

Forrest, watching the fruits of victory slip away, wired again later in the day to his superior: “Every moment lost is worth the life of a thousand men.” Still no reply came from Bragg. Finally beside himself, Forrest that night rode to see the General. The commander did not respond to Forrest’s impassioned pleas. Angry and frustrated, Forrest stormed from his superior’s tent. He later remarked to his orderly, “ I have written to him. I have sent to him. I have given him information on the condition of the Federal Army…What does he fight battles for?”

Bragg’s lack of forcefulness at Chickamauga had disastrous repercussions for the Confederacy. Lytle shows why in illuminating what amounted to the betrayal of Forrest’s clan rule by the Confederate officialdom in the aftermath of the battle. “Not until Bragg cast his shadow across the stage did the drama about to be played assume definitely its tragic forms. He was the shadow, the element that complicated the plot.” Aware of the dimension of his failure, Bragg blamed his shortcomings at Chickamauga on Forrest. The commander removed him from his command and appointed Major General Wheeler, whom Forrest disliked, to replace him. This so incensed and humiliated Forrest that he stormed to Bragg’s headquarters to tell him that if he dared cross his path again, he jeopardized his life.

Lytle shows this unfortunate standoff between the two leaders to be a drama revealing two different views of nationalism. Forrest represented the highly unorthodox ways of clan brotherhood, with military methods derived from a keen instinct for victory that could not be taught or learned in what might be considered orthodox military training. For instance, once as Forrest violated military precedent by sharpening both edges of a captured sword, he tersely remarked, “War means fighting and fighting means killing.” Still later in 1864, Forrest lost 500 men at the Battle of Harrisburg because of the foolish strategy of his superior, General Stephen D. Lee. Often profane, yet a master of the trenchant phrase, Forrest told Lee, “If I knew as much about West Point tactics as you, the Yankees would whip the hell out of me every day.”

Forrest came to loathe the professional soldiers who often envied his military feats and were threatened by his unpredictable tactics. Bragg, however, represented something worse than the blundering of Stephen Lee. There was more than poor strategy involved. In the case of the Bragg-Forrest antagonism, the frontiersman compromised his better judgment in gaining satisfaction by finally threatening Bragg.

Clan rule, as Lytle described it “Has its feuds and other sins of pride.” And Lytle tells us that Forrest “would pay a great price for settling his bile-he would make the South pay a great price-for he had done the Southern cause such an injury that all his genius would be powerless to repair it.” In the quarrel with Bragg, Forrest assumed that his superior shared in the unwritten frontier code of honor that would make him accept his subordinate’s rebuke in a manly fashion. Instead, Forrest’s pointed criticism provoked a sullen resentment that led to a determination to remove Forrest from any position of influence.

The personal animosity between the two gradually isolated Forrest even more from his superiors. This could not have come at a more inopportune time because, if Southern independence were to succeed, it was crucial that Confederate leaders finally see who was the most effective commander and what kind of virtues he inspired in his men. Lytle summarizes these traits in evaluating Forrest:

An officer usually controls his men in four ways:

Through fear, through respect, through love, or by his position. The last named is adequate for the garrison, but unreliable on the field. Fear alone is negative control and treacherous. Love and leniency too often go hand-in-hand producing sporadic results, while a soldier will, out of respect for the officer as a man, fight well so long

as there is no unusual emergency. But to fear and respect the commander’s military capacity at the same time brings the happiest results. An officer who possesses the hearts of his men by these two qualities holds his ranks in the palm of his hand. Bedford Forrest was such an officer.

But once Bragg removed Forrest from his command after the Battle of Chickamauga, the Confederacy lost this unique quality of leadership. Coupled with this disastrous decision was the Union policy after Chickamauga to wage a campaign against General Joseph E. Johnston, the object of which was to capture the city of Atlanta and to open the rest of Georgia to Sherman’s army. Had Forrest been utilized fully, particularly in cutting Sherman off from his base (Sherman even acknowledged that such a strategy would have troubled his campaign), his efforts might have been seriously impeded. After the Battle of Chickamauga, however, Forrest found himself relegated to insignificant roles in resisting both the “total war” policy of Sherman and the internal disintegration within Southern society itself.

In the dynamics of Sherman’s policy, it is evident that he understood the components of Confederate society: a military campaign waged against the population and Negro rebellion from within would combine to destroy the fabric of the state. Ironically, the Federal commander understood better than either General Bragg or President Davis what kind of policy he had to undertake to defeat Southern Nationalism. The Yankee leader was fully aware of what Forrest could do and what he represented. This is evident in Sherman’s reaction to the defeat of Union forces at the Battle of Brice’s Crossroads in North Mississippi where, according to Lytle, Forrest (in June, 1864) fought the finest small battle ever waged on the North American continent by using what Forrest called in his dialect, “the skeer.” General Sherman, in what must be one of the understatements of the conflict, wired the Secretary of War: “Forrest is the devil, and I think he has got some of our troops under cover.” Sherman went on to close his telegram with an ominous threat: “I will order them (A.J. Smith and Mower) to make up a force and go out to follow Forrest to the death, if it costs ten thousand lives and breaks the Treasury. There will never be peace in Tennessee until Forrest is dead. ”

Remarks such as these make the Confederate high command’s failure to utilize Forrest even more stark. And the isolation of Forrest’s talents damaged far more than the hopes of the Confederate soldiers on the battlefield. Forrest, as the clan leader, was also an extremely important symbol to the Southern women at home. To Forrest, the women in the folk nation of the South occupied a place or an office that demanded unequivocal defense. In fact, Forrest’s protection of the women’s position may be the single most important factor in understanding the essence of his commands.

The first chapter of the Lytle book, entitled “A Basket of Chickens”, illustrates that the women’s place was inviolable and any threat had to be severely punished. Undoubtedly, this is the reason that the young Bedford Forrest relentlessly tracked to the death a panther that attacked his mother. Such an attitude never changed in the transition from young frontiersman to military leader. This is evident in the recognition Forrest received early in the War from the ladies of Middle Tennessee. In July, 1862, Forrest in a daring maneuver, recaptured Murfreesboro, Tennessee, that had been held by the Federals. One lady, as Forrest’s victorious troops marched into the town, scooped the dirt from under the hoofs into her silk handkerchief as a keepsake. Later in the war the women of Middle Tennessee melted their thimbles and made the General a pair of silver spurs.

These are acts of thankfulness that emphasize yet again the power of clan nationalism. The dynamics of Southern society were more complex than the much publicized tradition of the planter-gentleman. Forrest superseded this; his exploits made him into the mythic hero of a national family. The ascendency of this kind of nationalism could preserve the tradition of the gentleman, but without it the genteel society would become only a hollow social convention.

The difference between these two understandings is evident in the differing views of Forrest and Lee after the Southern surrender at Appomattox. Forrest, when told of the news as he and an aide approached a crossroads, remarked: “If one of them led to hell and the other to Mexico, I wouldn’t care which one I took.” Forrest’s uncompromising resignation shows he differed from Lee. A chivalric man, Lee participated in what he thought to be a conditional defeat present in the terms of surrender; on the other hand, Forrest believed there were no acceptable “terms”, other than victory. In this case, he had an instinctive grasp of the grim phase the War was to enter, a grasp that General Lee did not see because of his own personal nobility. Lee misunderstood the form that Reconstruction was to take, whereas Forrest’s war experiences made him see the Appomattox surrender as simply a formality leading to a more subtle and brutal aspect of the War. Lytle writes:

…The old wounds were kept open by the Reconstruction policy and the worst form of guerrilla warfare. The avowed purpose of this policy, which broke the terms at Appomattox and Goldsboro, was the destruction of Southern civilization. Did Lee not see that the training of a few thousand students at Washington College was a futile thing if their civilization was to be wrecked?

This question illuminates once again Forrest’s devotion to the clan he led. And in its cohesive strength he saw the only way that the indignities and violence of the day-to-day working out of the Reconstruction policy could be resisted. But by this late date, Southern military nationalism was virtually finished, but Forrest remained the patriarch of the clan nation. Only upon reflection was the vital nature of this rule recognized. At Forrest’s funeral, Jefferson Davis remarked to Governor Porter of Tennessee about his misunderstanding of the great cavalryman: “The generals in the Southwest never appreciated Forrest until it was too late… I was misled by them…” The men who followed Forrest, however, and the women who joined them to form the Southern folk nation always understood and appreciated their hero. In fact, Lytle dedicates the story to his grandmother, who was a part of the Middle Tennessee matriarchy. Obviously, Lytle heard the tales of Forrest from his grandmother, “who heard on the hard turnpike the sudden beat of his horses’ hoofs and the wild yell of his riders.”

This kind of memory and excitement is also present in the final scene of Lytle’s book, some fifty years after Forrest’s death in the 1930’s. Georgiana, an old Negro nurse of a Memphis family, is looking at the bronze statue of Forrest erected to his memory in Memphis, Tennessee. She remarks of the great cavalryman that, “De Gin’ral’s hoss show is gittin’ poe.” The lady for whom she works takes the remark literally and replies that a statue “can’t lose weight.” Despite this, the old Negro woman still insists that Bedford’s mount is “poe.” When asked why, the nurse replies, “I don’t know’m. I regon de Gin’ral must ride him of a night.”

It is most significant that the old Negro nurse, at the conclusion, reflects on the statue. The irony is clear: the nurse is the interpreter of the mythic Forrest who is the icon of a nation. This recognition shows that Forrest has achieved a high place that cannot be understood altogether through mere intellectual inquiry.

This last scene of the Forrest biography, then, must take its place as one of the more important ones in all of the Vanderbilt Agrarian writings, for it suggests a subtlety not present at least in the title of the famous Southern manifesto, I’ll Take My Stand. The impact of the title has worked to blunt the soundness of the individual essays. The title encourages the notion that the South was a nation of hothead slaveowners determined to fight pitched battles in defense of the indefensible. Lytle recognized this weakness from the beginning in the choice of titles for the Southern manifesto. In a letter (on file in the Fugitive/Agrarian Archives at Vanderbilt University) written to Donald Davidson before the publication of I’ll Take My Stand, he writes, “My dislike, my chief dislike, is that it takes the same attitude that Jefferson Davis took. Since that was our first undoing, I feel we should escape from it in our second defense.”

In understanding what Lytle means by this, we must turn to the Forrest biography. What, for instance, the Negro nurse at the conclusion sees in Forrest, the Confederate President (as we have seen) never saw until it was too late. Lytle painstakingly renders the characteristics of a patriarchal nation that only in hindsight was understood by its leaders and important military men.

Lytle presents Forrest leading what Stanley Horn calls the “invisible empire.” The career of the rough-hewn cavalryman of frontier Tennessee suggests the unorthodox ways of folk wisdom and the essential character of an authentic nationalism. So it is that Bedford Forrest and His Critter Company has relevance today in understanding the nature of American military and political power. The Confederate high command had to learn the hard way that the fortunes of a nation could not rest alone on the trained intellect and the implementation of abstract concepts. Southern military history, particularly the heroic leadership of Bedford Forrest, illustrates that nationalism must ultimately reside in the exercise of patriarchal rule of a people. Of late, America has progressively lost this sense while grim variations of the pattern occur, for instance, in the fanatical religious revolutions in Islamic countries. The conquest of the American embassy in Iran and the hostage seizure presents a stark incidence of American nationalism reaching such a low ebb that another form usurped it, in this case a dangerous mixture of Islamic political and religious fundamentalism orchestrated by a primitive “patriarch-Ayatollah.” The irony is all the more pointed because the hostage seizure occurred during the presidency of a Georgian, an obvious heir to the tradition of Southern paternal command. But President Carter’s inability to fulfill such a heritage pales in comparison to what in tragic hindsight is the notorious mimicking of paternalistic rule by Lyndon Johnson, the Texan. In the early years of the Vietnam War, he stated that he was “not ready for American boys to do the fighting for Asian boys.” While the rhetorical flair of clan rule is present, the Vietnam War presents a wretched account of the waste of lives and treasure because of the very absence of patriarchal command in high offices, both military and political.

This condition, for instance, animates the epic novel James Webb wrote before his appointment by President Reagan as Secretary of the Navy. Webb’s novel, Fields of Fire (Bantam Books, 1979), frames the action in such a way as to emphasize the pluralism of American society in the individualistic backgrounds of the Marine characters. Webb draws portraits of the various kinds of men who found themselves at “the end of the Pipeline” in Southeast Asia—Snake, the inner city tough; Goodrich, the Harvard dropout; Cat-man, the Mexican-American, the eyes and ears of the squad; Cannonball, the “brother” who confronted the surrealistic violence of the bush and the racial tensions away from the front; Bagger, the incarnation of the unreflective team spirit spawned in high school athletics; and Robert E. Lee Hodges Jr., the Southern samurai (“But there was Vietnam, and so there would be honor. It was the fight, not the cause that mattered”).

Lieutenant Hodges’ background, the pure Southern strain, is only one of many in the diverse tapestry of the Marine Corps. Lieutenant Robert E. Lee Hodges is the legitimate heir to the tradition of patriarchal command and tries to dismiss his misgivings about Vietnam fatalism with his own personal history; “1 flinch when bullets tear the air in angry rents and yet I know that Father, and three farmer boys at Pickett’s Charge, felt a cutting edge that dropped them dead. How can I be bitter? You are my strength, you ghosts.” Hodges’ grimly frustrating search for heroic meaning in the presence of such overwhelming loss is a protest against anonymity. His groping for meaning suggests that the heritage of patriarchal command must be recovered.

Today, the trauma of Vietnam and the sensational fatalism of the media have encouraged cultural passivity, a “what’s the use” ennui that nothing can be done. Yet in the nuclear age, such attitudes must be mightily resisted because the stakes are much higher and ultimately concern the survival of the free world. Leaders like Forrest provide the models for the cultivation of a determined will and heroism by instinct.

James Webb, in a recent speech as Secretary of the Navy, touched on this heritage that earlier his fictional character, Lieutenant Robert E. Lee Hodges, had tried to confirm. In memorializing the heroic loss of thirty-seven sailors killed aboard the USS Stark, the Secretary proclaimed, “I was reminded of a frequent epitaph on the tombstones of Confederate soldiers: “How many dreams died here?” (Memorial Day Speech, Arlington National Cemetery, May 25, 1987). Secretary Webb provides a moving reminder of the nation’s patriarchal heritage. It is one that we dismiss or forget at our peril.

This article was originally published in the 1987 Summer Issue of Southern Partisan magazine.