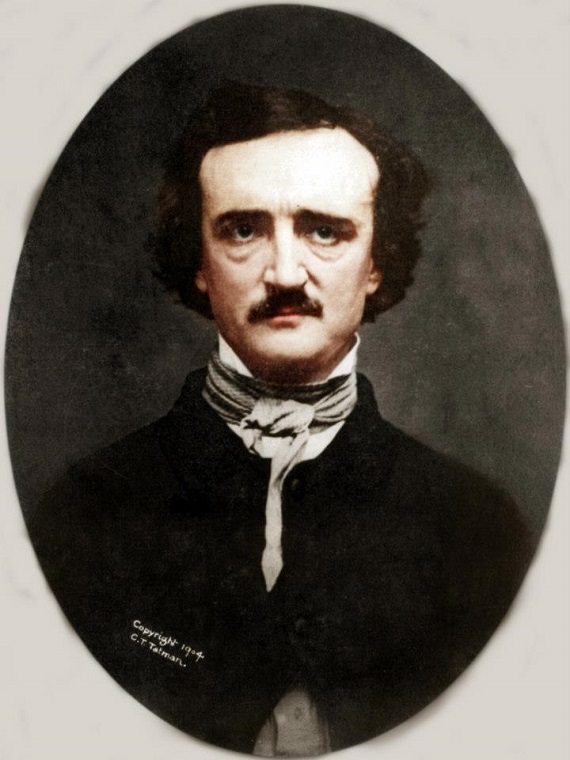

Edgar Allan Poe secured a permanent place among world authors as father of the short story, creator of the detective story, and/poetic genius. While he has an international reputation, Poe consciously identified himself as a Southern writer.

Poe may not often come to mind as a Southern writer because he did not write about the South the way Simms or, later, Faulkner did. Philosophically opposed to the use of literature for didactic purposes, Poe did not make the South the object of his writing. Nonetheless, his stories resonate with the attitudes and interests one might expect from a young Virginia gentleman educated at the University of Virginia and West Point.

His sojourn in South Carolina had a subtle influence on the setting for many of his stories and poems. The sea, the marshes, the deep semi-tropical forests hung with Spanish moss, the forbidding swamps, and the narrow causeway approaches to isolated plantation manors formed the setting for such stories as “The Gold Bug,” “The Oblong Box,” “The Man that was Used Up,” “The Balloon Hoax,” “The Fall of the House of Usher,” and “Annabel Lee.” Poe also pioneered in the introduction of black characters in American fiction.

Perhaps Poe’s most conspicuous contribution to Southern literature, however, was his defense of the right of other Southern writers to be heard. In his lifetime, Poe’s renown lay primarily in his reputation as the foremost critic of the day. As a critic he complained that four or five cliques controlled American literature by controlling the larger portion of the critical journals. When Rufus Griswold issued his Poets and Poetry of America in 1842, Poe observed that he might complain of Griswold’s “prepossession, evidently unperceived by himself, for the writers of New England.”

Poe could be bitingly sarcastic about the apparent conspiracy to censor the literary South. When Griswold gave Southern poetesses a fairer representation in The Female Poets of America, Poe congratulated him for being at “pains of doing what Northern critics seem to be at great pains never to do.” Griswold had gone to the trouble of doing justice to several poetesses who did not have “the good fortune to be born in the North.”

As an artist and critic, Poe did not commend the work of Southern writers simply because they were from the South. On the contrary, he joined battle because he determined that many fine writers could not have a fair hearing since they were from the South. Poe said it took courage to even hint “that anything good, in a literary way” could exist outside the narrow limits of the North.

In 1846 Poe published a series of articles in Godey’s Lady’s Book dealing with thirty-eight writers known to Poe, then resident in New York City. The articles appeared from May to November during which time the master of horror filled the literati of New York with terror over what he might say next. By the time the series was discontinued and answered with rebuttals and lawsuits, the episode came to be called The War of the Literati.

In his opening remarks, Poe charged that “the most ‘popular,’ the most ‘successful’ writers among us, (for a brief period, at least,) are, ninety-nine times out of a hundred, persons of mere address, perseverance, effrontery—in a word, busy-bodies, toadies, quacks.” He then proceeded to expose the self-protective, mutually congratulatory New York literary scene.

Poe singled out Longfellow and his New England group for particular attention. Though Poe acknowledged Longfellow as one of the foremost American poets, he also deplored the strangle hold the “frog-pond” set exerted on literature. Such cabals exercised an awesomely powerful literary control. A poor man like Hawthorne, though a genius, could not help but be unknown at the time since, in addition to his poverty he was not “an ubiquitous quack.” Longfellow, on the other hand, “although a little quacky perse, [had] through his social and literary position as a man of property and a professor at Harvard, a whole legion of active quacks at his control….”

Whenever he had the opportunity, Poe leveled a salvo at the “clique of pedants in and about Boston.” He had a particular dislike of the Bostonians’ predilection for grouping writers together for approval or disapproval. He noted that Boston critics “have a notion that poets are porpoises, (for they are always talking about their running in ‘schools,’)….”

Poe often cited William Gilmore Simms as a man neglected by the critics. While painfully pointing out Simms’ shortcomings, Poe strongly asserted Simms’ genius and complained that if he had been a Yankee “this genius would have been rendered immediately manifest to his countrymen, but unhappily (perhaps) he was a Southerner….”

In defending Bayard Taylor against a vicious criticism in the Literary World, Poe renewed his attack on the entrenched prejudice against Southerners and used the opportunity to point out how reviews were used “(as in the case of Simms,) to vilify, and vilify personally any one not a Northerner….”

In a review of The Wigwam and the Cabin (1845), Poe called Simms “the best novelist which’ this country has, upon the whole, produced” and spoke of his short story “Murder Will Out” as the best ghost story he had ever read. The New York Evening Mirror responded to Poe’s evaluation with an article entitled “Poe-lemical” and signed “*”. The article downgraded Poe as a critic and ridiculed Simms’ collected works stating that it would not bring the price in England or America of the single volume Norman Leslie by Theodore Fay. Fay edited the Mirror at the time.

In a letter to Evert Duyckinck, Simms complained about the “dirty fellows of the Mirror” and the “other dirty crawling creeping creature,” Lewis Gaylord Clarke of the Knickerbocker. In dismissing an article by Simms which complained of the absence of humor in American literature, Clarke said that the article appeared “in a Southern magazine, of small circulation and smaller influence, written by a very voluminous author, now in the decadence of a limited sectional reputation.” Such remarks reinforce Poe’s conclusion about Yankee literary bigotry.

Tension between North and South intensified during the decade. John C. Calhoun represented Southern interests in the United States Senate, but Edgar Allan Poe held the field in the literary struggle. In the March 1849 issue of The Southern Literary Messenger, Poe continued his crusade. James Russell Lowell had issued his satirical A Fable for Critics in 1848. Besides being an inferior piece of work in imitation of Byron’s “English Bards and Scotch Reviewers,” Poe charged the Fable with the basest of sectional bigotry. Poe called Lowell “one of the most rabid of the Abolition fanatics” and advised that “no Southerner who does not wish to be insulted, and at the same time revolted by a bigotry the most obstinately blind and deaf, should ever touch a volume” by Lowell.

A Fable for Critics represented just one more example of the neglect of the Southern literati by the literary establishment of the North. Poe anticipated and experienced at first hand the power of the media to mold not only political opinions, but also popular cultural attitudes and values. The literary powers of the North created a popular myth about the South as an ignorant region incapable of producing a literary corpus.

The crescendo of Poe’s criticism deserves to be quoted in full: “With the exception of Mr. Poe, (who has written some commendatory criticisms on his poems,) no Southerner is mentioned at all in this ‘Fable.’ It is a fashion among Mr. Lowell’s set to affect a belief that there is no such thing as Southern Literature. Northerners— people who have really nothing to speak of as men of letters—are cited by the dozen, and lauded by this candid critic without stint, while Legare, Simms, Longstreet, and others of equal note are passed by in contemptuous silence.”

When Augustus Baldwin Longstreet published his Georgia Scenes, Poe had praised it in a way he praised few works. He usually took pains to point out the failings of the works he praised the most, a habit which did not endear him to anyone. With Georgia Scenes, however, he could only exult in the joy of reading a truly humorous work. When it first appeared in the 1830’s, Poe called it “a sure omen of better days for literature of the South.” By the 1840’s, Poe knew better.

Poe also lamented the way critics had neglected Professor Beverley Tucker’s George Balcombe. Once again he attributed its neglect to the bigotry that ignored most of what happened south of Mason and Dixon’s line. Except for Tucker’s Southern birth, Poe believed his book would have been recognized as “one of the noblest fictions ever written by an American.”

In Prose Writers of America, Griswold declared that the South was composed largely of a wealthy, idle class that had done “comparatively nothing in the field of intellectual exertion.” Poe challenged this widely-held attitude in his reviews, which earned him the enmity of editors ranging from Griswold to Horace Greeley. The Northern press debated his critical assessments, assigning his unfavorable reviews of Northern writers to severe bitterness and assigning his favorable reviews of Southern writers to blind sectionalism. In reality, Poe may have been more severe with Southern writers because of his unwillingness for them to produce second-rate literature. Simms certainly learned from Poe’s appraisal of The Partisan.

Bickering over Poe’s favorable reviews of Southern writers did not end with Poe’s death. In the next generation one of Poe’s biographers dismissed his favorable reviews of Southerners as absurdities: “He was as extreme in eulogy as in denunciation; and, especially in the case of the Southern writers, he sometimes indulged in so laudatory a strain as to be guilty of absurdity.” Poe had experienced the same exclusion from notice which the other Southerners had experienced. He struggled against the closed shop system of literature that prevailed, and only by fierce determination did he begin to gain a degree of personal recognition after the publication of “The Raven” in 1845. He did not think other Southerners should have to face the same struggle. To help rectify the condition, Poe proposed the establishment of a new journal, The Stylus, as a forum for writers of talent who were being ignored as a matter of form.

Unfortunately, Poe had the very poor judgment to die in October 1849. His dream of a new journal died with him, and he left the literary scene without a successor of equal stature to advocate for the South in the literary halls. Worse for him personally, Poe predeceased his literary enemies who then had the opportunity for revenge. Griswold took the lead in smearing Poe’s reputation. Sadly, even in the South the slanderous traditions about Poe have persisted and been accepted as fact along side the belief “that there is no such thing as Southern Literature.”

Griswold began the attacks on Poe’s character with the obituary he wrote for Horace Greeley’s New York Daily Tribune under the pseudonym of “Ludwig.” The obituary began: “Edgar Allan Poe is dead. He died in Baltimore the day before yesterday. This announcement will startle many, but few will be grieved by it.” George Graham of Graham’s Magazine called Griswold’s ensuing smears a vendetta against Poe because of the critical remarks about Griswold and his friends. He said that Griswold’s “present hacking at the cold remains of him who struck them down, is a sort of compensation.” Graham’s voice, however, did not have the range of Griswold.

Though Griswold never forgave Poe’s criticism of his work, he had ingratiated himself to Poe after an initial period of estrangement and became Poe’s literary executor. The consummate editor, Griswold issued Poe’s works complete with memoir in which he quoted freely from personal papers to discredit Poe. As the authorized biographer, Griswold and his stories achieved canonical authority. Not until Professor A. H. Quinn’s definitive biography of 1941 were the papers exposed as forgeries!

During the period of the War of the Literati, Poe had been in a particularly agitated condition and broken state. Griswold attributed Poe’s condition to opium. In the next generation, the biographers continued the story. George Woodberry, standing in the New England transcendental tradition, attributed Poe’s condition in the mid-1840’s to liquor and “the more insidious and mortal influence of the use of opium, which, vampire-like, had sucked the vitality out of the whole frame of his being, mental, moral, and physical.” While none of Poe’s contemporaries had knowledge of his use of opium, Woodberry produced a letter written in 1884 by a cousin of Poe who recalled hearing another cousin say she believed Poe must have taken opium! The psychological biographers, who read between the lines even better than they read the printed page, point to Poe’s stories which mention drug use as proof of his dependency.

Oddly, the same scholars rarely suggest that Poe descended into a maelstrom, discovered a buried treasure, barely escaped being cut in two by a swinging pendulum, or crossed the Atlantic in a balloon, as his stories suggest.

In fact, Poe was in a dreadful state during the period mentioned. He was irritable, rude, short of temper, offensive, and impatient with the people who controlled the literary world. From 1842 to 1847 Poe watched helplessly as his beautiful young wife slowly died of tuberculosis. Time and again she hemorrhaged, and hovered near death, only to recover until the inevitable next time. The specter of death cast its shadow on his home for five years. The anticipation of his wife’s death sent Poe into a dreadful state of clinical depression.

In describing this time of his life, Poe wrote to George Eveleth: “I became insane, with long intervals of horrible sanity. During those fits of absolute unconsciousness, I drank—God only knows how often or how much. As a matter of course, my enemies referred the insanity to the drink rather than the drink to the insanity.” In his intense anticipatory grief, Poe was in no mood to be polite to the literary cabal that rewarded mediocrity. As regards his temper, he was the Preston Brooks of the press.

Griswold offered an explanation for Poe’s erratic condition during episodes of Virginia Poe’s prolonged death, and the Yankee literati were only too willing to believe someone would have to be crazy or doped to criticize them. It took voices from abroad to challenge the Griswold picture of Poe. In France, Baudelaire called Griswold a “pedagogic vampire” and asked, “Does there not exist in America an ordinance to keep dogs out of the cemeteries?” In England, John Ingram produced the first serious challenge to the Griswold stories in 1874 and continued the battle with the American traductionists until his death in 1916.

For all the responsible scholarship which has cleared Poe’s reputation, Griswold and the Yankee literati won the War of the Literati. The public has accepted the Griswold stories. Even this article which intended to discuss Poe as a proponent and defender of Southern writers was required to stir Griswold’s muck once again.